Washington, DC 1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Smithsonian Folklife Festival

I SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL .J HAITI Freedom and Creativity from the Mountains to the Sea NUESTRA MUSICA Music in Latino Culture WATER WAYS Mid-Atlantic Maritime Communities The annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival brings together exemplary keepers of diverse traditions, both old and new, from communities across the United States and around the world. The goal of the Festival is to strengthen and preserve these traditions by presenting them on the National Mall, so that the traciition-bearers and the public can connect with and learn from one another, and understand cultural differences in a respectful way. Smiths (JNIAN Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 750 9th Street NW Suite 4100 Washington, DC 20560-0953 www.folklife.si.edu © 2004 by the Smithsonian Institution ISSN 1056-6805 Editor: Carla Borden Associate Editors: Frank Proschan, Peter Seitel Art Director: Denise Arnot Production Manager: Joan Erdesky Graphic Designer: Krystyn MacGregor Confair Printing: Schneidereith & Sons, Baltimore, Maryland FESTIVAL SPONSORS The Festival is supported by federally appropriated funds; Smithsonian trust tunds; contributions from governments, businesses, foundations, and individuals; in-kind assistance; and food, recording, and cratt sales. The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service. Major hinders for this year's programs include Whole Foocis Market and the Music Performance Fund. Telecommunications support tor the Festival has been provided by Motorola. Nextel. Pegasus, and Icoiii America. Media partners include WAMU 88.5 FM, American University Radio, and WashingtonPost.com. with in-kind sup- port from Signature Systems and Go-Ped. Haiti: Frcciioin and Creativity fnvu the Moiiiitdiin to the Sea is produced in partnership with the Ministry of Haitians Living Abroad and the Institut Femmes Entrepreneurs (IFE), 111 collaboration with the National Organization for the Advancement of Haitians, and enjoys the broad-based support of Haitians and triends ot Haiti around the world. -

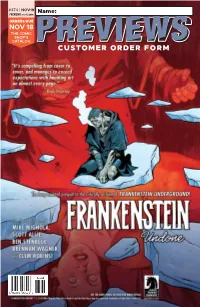

Customer Order Form

#374 | NOV19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:23:57 PM Nov19 CBLDF Ad.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:36:53 PM PROTECTOR #1 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS SPIDER-MAN #1 IDW PUBLISHING WONDER WOMAN #750 SEX CRIMINALS #26 DC COMICS IMAGE COMICS IRON MAN 2020 #1 MARVEL COMICS BATMAN #86 DC COMICS STRANGER THINGS: INTO THE FIRE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS RED SONJA: AGE OF CHAOS! #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SONIC THE HEDGEHOG #25 IDW PUBLISHING FRANKENSTEIN HEAVY VINYL: UNDONE #1 Y2K-O! OGN SC DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS NOv19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 4:18:59 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS • GRAPHIC NOVELS KIDZ #1 l ABLAZE Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower HC l ABRAMS COMICARTS Cat Shit One #1 l ANTARCTIC PRESS 1 Owly Volume 1: The Way Home GN (Color Edition) l GRAPHIX Catherine’s War GN l HARPER ALLEY BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams HC l INSIGHT COMICS The Plain Janes GN SC/HC l LITTLE BROWN FOR YOUNG READERS Nils: The Tree of Life HC l MAGNETIC PRESS 1 The Sunken Tower HC l ONI PRESS The Runaway Princess GN SC/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC White Ash #1 l SCOUT COMICS Doctor Who: The 13th Doctor Season 2 #1 l TITAN COMICS Tank Girl Color Classics ’93-’94 #3.1 l TITAN COMICS Quantum & Woody #1 (2020) l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Vagrant Queen: A Planet Called Doom #1 l VAULT COMICS BOOKS • MAGAZINES Austin Briggs: The Consummate Illustrator HC l AUAD PUBLISHING The Black Widow Little Golden Book HC l GOLDEN BOOKS -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

2 22 37 55 68 90 W Numerze 11 26 42 58 78

Dwumiesięcznik W NUMERZE Vol. XVIII, Nr 5/2011 (109) ISSN-1231-014X, Indeks 386138 Redaktor naczelny Jarosław Malinowski Juliusz Tomczak Pancernik wielkich nadziei – historia CSS 2 Kolegium redakcyjne Rafał Ciechanowski, Michał Jarczyk, „Virginia”, część II Maciej S. Sobański Współpracownicy w kraju Andrzej S. Bartelski, Jan Bartelski, Alejandro A. Anca, Nikołaj W. Mitiuckow Stanisław Biela, Jarosław Cichy, 11 Krążowniki Portugalii Andrzej Danilewicz, Józef Wiesław Dyskant, Maciej K. Franz, Przemysław Federowicz, Michał Glock, Tadeusz Górski, Jarosław Jastrzębski, Rafał Mariusz Kaczmarek, Jerzy Lewandowski, Oskar Myszor, Andrzej Nitka, Piotr Nykiel, Michał Jarczyk, Krzysztof Krzeszowiak Grzegorz Ochmiński, Jarosław Palasek, Jednostka torpedowa „Zieten” 22 Jan Radziemski, Marek Supłat, Cesarskiej marynarki wojennej Niemiec Tomasz Walczyk, Kazimierz Zygadło Współpracownicy zagraniczni BELGIA Leo van Ginderen Aleksandr Aleksandrow, Siergiej Bałakin CZECHY 26 „Asama” i kuzyni, częć IV Ota Janeček FRANCJA Gérard Garier, Jean Guiglini, Pierre Hervieux HISZPANIA Alejandro Anca Alamillo LITWA Jarosław Jastrzębski Aleksandr Mitrofanov O potrzebie wyodrębnienia w nomenklaturze 37 NIEMCY okrętowej klasy „hydroplanowca” Richard Dybko, Hartmut Ehlers, Jürgen Eichardt, Christoph Fatz, Zvonimir Freivogel, Reinhard Kramer ROSJA Siergiej W. Patjanin Siergiej A. Bałakin, Nikołaj W. Mitiuckow, 42 Od Sallum do Syrty. Flota w Kampanii Konstantin B. Strelbickij Północnoafrykańskiej lat 1940-1941 STANY ZJEDNOCZONE. A.P. Arthur D. Baker III UKRAINA Anatolij N. Odajnik, Władimir P. Zabłockij WŁOCHY Rafał Mariusz Karczmarek Maurizio Brescia, Achille Rastelli „Lancastery” nad Sassnitz 55 Adres redakcji Wydawnictwo „Okręty Wojenne” Krzywoustego 16, 42-605 Tarnowskie Góry Polska/Poland tel: +48 32 384-48-61 www.okretywojenne.pl Andrij Kharuk e-mail: [email protected] 58 Niszczyciele typu „Battle”, część II Skład, druk i oprawa: DRUKPOL sp. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Electric Marine Vessels and Aquanaut Crafts

ELECTRIC MARINE VESSELS AND AQUANAUT CRAFTS. [3044] The invention is related to Electro motive and electric generating clean and green, Zero Emission and sustainable marine vessels, ships, boats and the like. Applicable for Submersible and semisubmersible vessels as well as Hydrofoils and air-cushioned craft, speeding on the body of water and submerged in the body of water. The Inventions provides a Steam Ship propelled by the kinetic force of steam or by the generated electric current provided by the steam turbine generator to a magnet motor and generator. Wind turbine provided on the above deck generating electric current by wind and hydroelectric turbines made below the hull mounted under the hull. Mounted in the duct of the hull or in the hull made partial longitudinal holes. Magnet motor driven the rotor in the omnidirectional nacelle while electricity is generating in the machine stator while the turbine rotor or screw propeller is operating. The turbine rotor for propulsion is a capturing device in contrary to a wind, steam turbine or hydro turbine rotor blades. [3045] The steam electric ship generates electricity and desalinates sea water when applicable. [3046] Existing propulsion engines for ships are driven by diesel and gas engines and hybrid engines, with at least one angle adjustable screw propeller mounted on the propeller shaft with a surrounding tubular shroud mounted around the screw propeller with a fluid gap or mounted without a shroud mounted below the hull at the aft. The duct comprises: a first portion of which horizontal width is varied from one side to the other side; and a second portion connected to one side of the first portion and having the uniform horizontal width. -

1 May 2015 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 25 April – 1 May 2015 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 25 APRIL 2015 SAT 06:30 Farming Today (b05rk5tb) In 1915 we start to see how artists, like poet Guillaume Farming Today This Week: Countryfile Farming Hero Robert Apollinaire and Rudyard Kipling, are responding to war, and SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b05qvz8f) Bertram explore an unlikely alliance of the avant-garde and the military. The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Followed by Weather. Robert Bertram has lived in the same valley in Northumberland World War One altered the ways in which men and women since he was born, in 1947, and his local knowledge was crucial thought about the world, and about culture and its expressions. to saving his neighbour's life in January this year. SAT 00:30 Skyfaring: A Journey with a Pilot (b05pr1jd) During the bloody battle at Gallipoli, Australia's sense of Episode 5 A blizzard was raging when, late one evening, Laura Hudson identity started to take shape. But national bonds were also came to Robert's door with her two very young children. Her beginning to weaken as war shattered allegiances and fractured Landing, flying blind and coming home. partner, Mark Dey, had failed to return from the hill where he'd borders. been feeding sheep, and because her phone was cut off, she had Mark Vanhoenacker always had a passion for flying, but didn't struggled to get the family into the car to drive and get help. We look at the ways in which new perspectives entered the ever really consider it as a job, until his research as a young Robert didn't hesitate to set out in search of Mark. -

The Archaeology of Virginia's Long Seventeenth Century, 1550-1720: Previous Research and Future Directions

The Archaeology of Virginia's Long Seventeenth Century, 1550-1720: Previous Research and Future Directions Dennis J. Pogue Time Line x 1561-66: Spanish expeditions from Havana and La Florida explore the Chesapeake Bay in search of trade routes to the west and to scout potential sites for settlement. x 1570: Jesuit priests establish the Ajacan mission on the York River in an attempt to Christianize the native Indians; the venture fails the next year when the priests are killed by the natives. x 1607: The English establish their first permanent settlement in Virginia when 104 colonists disembark at Jamestown Island and erect James Fort. x 1607-08: John Smith and his crew explore the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries by boat; the Englishmen record the locations of the Indian settlements they pass. x 1609-14: Colonists and the Powhatan Indians engage in a series of armed conflicts as the natives attempt to protect their rights to the land. x 1614: English settlers begin to cultivate tobacco, which becomes the primary source of wealth for the colony for the next 200 years. x 1617-22: Twenty-three "particular plantations," or subsidiary corporations controlled by stock holders, are created as part of an attempt to encourage immigration and the spread of settlement beyond Jamestown. x 1619: The first enslaved Africans are introduced to Virginia; the first representative legislative assembly is formed. x 1622: 200,000 pounds of tobacco are shipped out of Virginia; the homes of 1500 settlers spread for 50 miles along the James River; in response to the pressures of continued immigration of Englishmen, the Powhatan Indians attack and kill several hundred settlers in a series of coordinated attacks. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

The Martinak Boat (CAR-254, 18CA54) Caroline County, Maryland

The Martinak Boat (CAR-254, 18CA54) Caroline County, Maryland Bruce F. Thompson Principal Investigator Maryland Department of Planning Maryland Historical Trust, Office of Archeology Maryland State Historic Preservation Office 100 Community Place Crownsville, Maryland 21032-2023 November, 2005 This project was accomplished through a partnership between the following organizations: Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Department of Natural Resources Martinak State Park Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Maritime Archaeological and Historical Society *The cover photo shows the entrance to Watts Creek where the Martinak Boat was discovered just to the right of the ramp http://www.riverheritage.org/riverguide/Sites/html/watts_creek.html (accessed December 10, 2004). Executive Summary The 1960s discovery and recovery of wooden shipwreck remains from Watt’s Creek, Caroline County induced three decades of discussion, study and documentation to determine the wrecks true place within the region’s history. Early interpretations of the wreck timbers claimed the vessel was an example of a Pungy (generally accepted to have been built ca. 1840 – 1920, perhaps as early as 1820), with "…full flaring bow, long lean run, sharp floors, flush deck…and a raking stem post and stern post" (Burgess, 1975:58). However, the closer inspection described in this report found that the floors are flatter and the stem post and stern post display a much longer run (not so raking as first thought). Additional factors, such as fastener types, construction details and tool marks offer evidence for a vessel built earlier than 1820, possibly a link between the late 18th-century shipbuilding tradition and the 19th-century Pungy form. The Martinak Boat (CAR-254, 18CA54) Caroline County, Maryland Introduction In November, 1989 Maryland Maritime Archeology Program (MMAP) staff met with Richard Dodds, then curator of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum (CBMM), and Norman H. -

Pocahontas's Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty

言語・地域文化研究 第 ₂6 号 2020 103 Pocahontas’s Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty Hiroyuki Tsukada ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ 塚田 浩幸 要 旨 ポカホンタスは、二度、ジョン・スミスの命を救った。一度目は有名な助命で、1607 年 12 月、インディアンの首長パウハタンによる処刑の寸前に、ポカホンタスが捕虜スミ スに自分の体をなげうって助命をした。これは、スミスの死と生まれ変わりを象徴的に 意味し、入植者をインディアンの世界に迎え入れる儀式で、ポカホンタスはスミスを救 うというあらかじめ決められた役割を担った。この一度目の助命の真偽については長ら く論争が行なわれてきたが、スミスが 1608 年 6 月の報告書簡でポカホンタスを「比類な き人物」と高く評価できたという事実は、助命が実際に起きたことを示している。その 6 月の時点で、スミスは助命の他に、取引や物資の提供と人質解放交渉の場面でポカホ ンタスと会う機会を持っていたが、それらの場面においては、スミスが「比類なき人物」 と評価することができるほどの行動をポカホンタスがとっていなかったからである。そ して、スミスがその報告書簡でポカホンタスを紹介したのは、入植事業の宣伝のために インディアンとの平和友好をアピールするねらいがあった。つまり、スミスに批判的な 研究者が主張するように、スミスがポカホンタスの人気にあやかって自分の名声をあげ るために助命を捏造したのではなく、助命に感銘を受けたスミスがポカホンタスの人気 を作り上げたといえるのである。 パウハタンは、一度目の助命でポカホンタスをインディアンと入植者の平和友好のシ ンボルとして仕立て上げ、その後の平和的な外交の場面にもポカホンタスを同行させて いた。しかしながら、二度目の助命は、パウハタンの外交方針に逆らって、ポカホンタ ス自身の意思によって行なわれた。1609 年 1 月、インディアンと入植者の関係が悪化す るなか、パウハタンがスミスを本当に襲おうとしているところをポカホンタスがスミス に密告して救った。この二つの助命のあいだの期間、ポカホンタスは入植者と頻繁に会 うなかで理解を深め、パウハタン連合のインディアンとしての忠誠心に揺らぎを生じさ せていたのである。つまり、ポカホンタスは、単なるパウハタンの遣いとしての平和友 好のシンボルであることをやめ、自らを平和友好の使者として確立させるに至ったので ある。 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示 4.0 国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 104 論文 ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ (塚田 浩幸) Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. A special relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith 3. Refutation of all existing theories 4. Demonstration of the veracity of the rescue 5. Conclusion 1. Introduction Pocahontas saved John Smith twice. The frst instance came in December 1607, when she symbolically ofered her own head to save Smith’s