Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dena Derose, Vocals and Piano Martin Wind, Bass • Matt Wilson, Drums with Sheila Jordan, Vocal • Jeremy Pelt, Trumpet Houston Person, Tenor Saxophone

19 juin, 2020. June 19, 2020. MAN MAN DREAM HUNTING IN THE VALLEY OF THE IN-BETWEEN CD / 2XLP / CS / DIGITAL SP 1350 RELEASE DATE: MAY IST, 2020 TRACKLISTING: 1. Dreamers 2. Cloud Nein 3. On the Mend 4. Lonely Beuys 5. Future Peg 6. Goat 7. Inner Iggy 8. Hunters 9. Oyster Point 10. The Prettiest Song in the World 11. Animal Attraction 12. Sheela 13. Unsweet Meat 14. Swan 15. Powder My Wig 16. If Only 17. In the Valley of the In-Between GENRE: Alternative Rock Honus Honus (aka Ryan Kattner) has devoted his career to exploring the uncertainty between life’s extremes, beauty, and ugliness, order and chaos. The songs on Dream Hunting in the Valley of the In-Between, Man Man’s first album in over six years and their Sub Pop debut, are as intimate, soulful, and timeless as they are audaciously inventive and daring, resulting in his best Man Man album to date. 0 9 8 7 8 7 1 3 5 0 2 209 8 7 8 7 1 3 5 0 1 5 CD Packaging: Digipack 2xLP Packaging: Gatefold jacket w/ custom The 17-track effort, featuring “Cloud Nein,” “Future Peg,” “On the with poster insert dust sleeves and etching on side D Includes mp3 coupon Mend” “Sheela,” and “Animal Attraction,” was produced by Cyrus NON-RETURNABLE Ghahremani, mixed by S. Husky Höskulds (Norah Jones, Tom Waits, Mike Patton, Solomon Burke, Bettye LaVette, Allen Toussaint), and mastered by Dave Cooley (Blood Orange, M83, DIIV, Paramore, Snail Mail, clipping). Dream Hunting...also includes guest vocals from Steady Holiday’s Dre Babinski on “Future Peg” and “If Only,” and Rebecca Black (singer of the viral pop hit, “Friday”) on “On The Mend” and “Lonely Beuys.” The album follows the release of “Beached” and “Witch,“ Man Man’s contributions to Vol. -

June 26, 1995

Volume$3.00Mail Registration ($2.8061 No. plusNo. 1351 .20 GST)21-June 26, 1995 rn HO I. Y temptation Z2/Z4-8I026 BUM "temptation" IN ate, JUNE 27th FIRST SIN' "jersey girl" r"NAD1AN TOUR DATES June 24 (2 shows) - Discovery Theatre, Vancouver June 27 a 28 - St. Denis Theatre, Montreal June 30 - NAC Theatre, Ottawa July 4 - Massey Hall, Toronto PRODUCED BY CRAIG STREET RPM - Monday June 26, 1995 - 3 theUSArts ireartstrade of and andrepresentativean artsbroadcasting, andculture culture Mickey film, coalition coalition Kantorcable, representing magazine,has drawn getstobook listdander publishing companiesKantor up and hadthat soundindicated wouldover recording suffer thatKantor heunder wasindustries. USprepared trade spokespersonCanadiansanctions. KeithThe Conference for announcement theKelly, coalition, nationalof the was revealed Arts, expecteddirector actingthat ashortly. of recent as the a FrederickPublishersThe Society of Canadaof Composers, Harris (SOCAN) Authors and and The SOCANand Frederick Music project.the preview joint participation Canadian of SOCAN and works Harris in this contenthason"areGallup the theconcerned information Pollresponsibilityto choose indicated about from.highway preserving that to He ensure a and alsomajority that our pointedthere culturalthe of isgovernment Canadiansout Canadian identity that in MusiccompositionsofHarris three MusicConcert newCanadian Company at Hallcollections Toronto's on pianist presentedJune Royal 1.of Monica Canadian a Conservatory musical Gaylord preview piano of Chatman,introducedpresidentcomposers of StevenGuest by the and their SOCAN GellmanGaylord.speaker respective Foundation, and LouisThe composers,Alexina selections Applebaum, introduced Louie. Stephen were the originatethatisspite "an 64% of American the ofKelly abroad,cultural television alsodomination policies mostuncovered programs from in of place ourstatisticsscreened the media."in US; Canada indicatingin 93% Canada there of composersdesignedSeriesperformed (Explorations toThe the introduceinto previewpieces. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

The-Desire-Of-Ages.Pdf

The Desire of Ages Ellen G. White 1898 Copyright © 2011 Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. Information about this Book Overview This eBook is provided by the Ellen G. White Estate. It is included in the larger free Online Books collection on the Ellen G. White Estate Web site. About the Author Ellen G. White (1827-1915) is considered the most widely translated American author, her works having been published in more than 160 languages. She wrote more than 100,000 pages on a wide variety of spiritual and practical topics. Guided by the Holy Spirit, she exalted Jesus and pointed to the Scriptures as the basis of one’s faith. Further Links A Brief Biography of Ellen G. White About the Ellen G. White Estate End User License Agreement The viewing, printing or downloading of this book grants you only a limited, nonexclusive and nontransferable license for use solely by you for your own personal use. This license does not permit republication, distribution, assignment, sublicense, sale, preparation of derivative works, or other use. Any unauthorized use of this book terminates the license granted hereby. Further Information For more information about the author, publishers, or how you can support this service, please contact the Ellen G. White Estate at [email protected]. We are thankful for your interest and feedback and wish you God’s blessing as you read. i ii Preface In the hearts of all mankind, of whatever race or station in life, there are inexpressible longings for something they do not now possess. This longing is implanted in the very constitution of man by a merciful God, that man may not be satisfied with his present conditions or attainments, whether bad, or good, or better. -

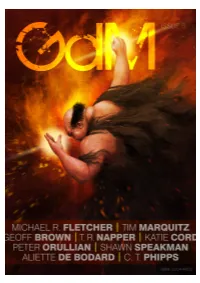

Grimdark-Magazine-Issue-6-PDF.Pdf

Contents From the Editor By Adrian Collins A Fair Man From The Vault of Heaven By Peter Orullian The Grimdark Villain Article by C.T. Phipps Review: Son of the Black Sword Author: Larry Correia Review by malrubius Excerpt: Blood of Innocents By Mitchell Hogan Publisher Roundtable Shawn Speakman, Katie Cord, Tim Marquitz, and Geoff Brown. Twelve Minutes to Vinh Quang By T.R. Napper Review: Dishonoured By CT Phipps An Interview with Aliette de Bodard At the Walls of Sinnlos A Manifest Delusions developmental short story by Michael R. Fletcher 2 The cover art for Grimdark Magazine issue #6 was created by Jason Deem. Jason Deem is an artist and designer residing in Dallas, Texas. More of his work can be found at: spiralhorizon.deviantart.com, on Twitter (@jason_deem) and on Instagram (spiralhorizonart). 3 From the Editor ADRIAN COLLINS On the 6th of November, 2015, our friend, colleague, and fellow grimdark enthusiast Kennet Rowan Gencks passed away unexpectedly. This one is for you, mate. Adrian Collins Founder Connect with the Grimdark Magazine team at: facebook.com/grimdarkmagazine twitter.com/AdrianGdMag grimdarkmagazine.com plus.google.com/+AdrianCollinsGdM/ pinterest.com/AdrianGdM/ 4 A Fair Man A story from The Vault of Heaven PETER ORULLIAN Pit Row reeked of sweat. And fear. Heavy sun fell across the necks of those who waited their turn in the pit. Some sat in silence, weapons like afterthoughts in their laps. Others trembled and chattered to anyone who’d spare a moment to listen. Fallow dust lazed around them all. The smell of old earth newly turned. -

Nomads of the North

Nomads of the North A Story of Romance and Adventure under the Open Stars by James Oliver Curwood, 1878-1927 Published: 1919 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Chapter 1 … thru … Chapter 26 J J J J J I I I I I Chapter 1 It was late in the month of March, at the dying-out of the Eagle Moon, that Neewa the black bear cub got his first real look at the world. Noozak, his mother, was an old bear, and like an old person she was filled with rheumatics and the desire to sleep late. So instead of taking a short and ordinary nap of three months this particular winter of little Neewa's birth she slept four, which, made Neewa, who was born while his mother was sound asleep, a little over two months old instead of six weeks when they came out of den. In choosing this den Noozak had gone to a cavern at the crest of a high, barren ridge, and from this point Neewa first looked down into the valley. For a time, coming out of darkness into sunlight, he was blinded. He could hear and smell and feel many things before he could see. And Noozak, as though puzzled at finding warmth and sunshine in place of cold and darkness, stood for many minutes sniffing the wind and looking down upon her domain. For two weeks an early spring had been working its miracle of change in that wonderful country of the northland between Jackson's Knee and the Shamattawa River, and from north to south between God's Lake and the Churchill. -

Doctor of Philosophy

RICE UNIVERSITY By tommy symmes A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE William B Parsons William B Parsons (Apr 21, 2021 11:48 PDT) William Parsons Jeffrey Kripal Jeffrey Kripal (Apr 21, 2021 13:45 CDT) Jeffrey Kripal James Faubion James Faubion (Apr 21, 2021 14:17 CDT) James Faubion HOUSTON, TEXAS April 2021 1 Abstract This dissertation studies dance music events in a field survey of writings, in field work with interviews, and in conversations between material of interest sourced from the writing and interviews. Conversations are arranged around six reading themes: events, ineffability, dancing, the materiality of sound, critique, and darkness. The field survey searches for these themes in histories, sociotheoretical studies, memoirs, musical nonfiction, and zines. The field work searches for these themes at six dance music event series in the Twin Cities: Warehouse 1, Freak Of The Week, House Proud, Techno Tuesday, Communion, and the Headspace Collective. The dissertation learns that conversations that take place at dance music events often reflect and engage with multiple of the same themes as conversations that take place in writings about dance music events. So this dissertation suggests that writings about dance music events would always do well to listen closely to what people at dance music events are already chatting about, because conversations about dance music events are also, often enough, conversations about things besides dance music events as well. 2 Acknowledgments Thanks to my dissertation committee for reading this dissertation and patiently indulging me in conversations about dance music events. -

Hallo Zusammen

Hallo zusammen, Weihnachten steht vor der Tür! Damit dann auch alles mit den Geschenken klappt, bestellt bitte bis spätestens Freitag, den 12.12.! Bei nachträglich eingehenden Bestellungen können wir keine Gewähr übernehmen, dass die Sachen noch rechtzeitig bis Weihnachten eintrudeln! Vom 24.12. bis einschließlich 5.1.04 bleibt unser Mailorder geschlossen. Ab dem 6.1. sind wir aber wieder für euch da. Und noch eine generelle Anmerkung zum Schluss: Dieser Katalog offeriert nur ein Bruchteil unseres Gesamtangebotes. Falls ihr also etwas im vorliegenden Prospekt nicht findet, schaut einfach unter www.visions.de nach, schreibt ein E-Mail oder ruft kurz an. Viel Spass beim Stöbern wünscht, Udo Boll (VISIONS Mailorder-Boss) NEUERSCHEINUNGEN • CDs VON A-Z • VINYL • CD-ANGEBOTE • MERCHANDISE • BÜCHER • DVDs ! CD-Angebote 8,90 12,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 12,90 Bad Astronaut Black Rebel Motorcycle Club Cave In Cash, Johnny Cash, Johnny Elbow Jimmy Eat World Acrophobe dto. Antenna American Rec. 2: Unchained American Rec. 3: Solitary Man Cast Of Thousands Bleed American 12,90 7,90 12,90 9,90 12,90 8,90 12,90 Mother Tongue Oasis Queens Of The Stone Age Radiohead Sevendust T(I)NC …Trail Of Dead Ghost Note Be Here Now Rated R Amnesiac Seasons Bigger Cages, Longer Chains Source Tags & Codes 4 Lyn - dto. 10,90 An einem Sonntag im April 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Significant Other 11,90 Plant, Robert - Dreamland 12,90 3 Doors Down - The Better Life 12,90 Element Of Crime - Damals hinterm Mond 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Three Dollar Bill Y’all 8,90 Polyphonic Spree - Absolute Beginner -Bambule 10,90 Element Of Crime - Die schönen Rosen 10,90 Linkin Park - Reanimation 12,90 The Beginning Stages Of 12,90 Aerosmith - Greatest Hits 7,90 Element Of Crime - Live - Secret Samadhi 12,90 Portishead - PNYC 12,90 Aerosmith - Just Push Play 11,90 Freedom, Love & Hapiness 10,90 Live - Throwing Cooper 12,90 Portishead - dto. -

(CFUZ-FM). Host

My Morning Racket is a weekly two-hour radio show produced in Penticton British Columbia at Peach City Radio (CFUZ-FM). Host Dave Del Rizzo thumbs his nose at the conventional kid gloves used to wake folks via radio music by playing loud unapologetic distortion-laden music for breakfast. Mix in a little talk and the occasional interview, and voila, welcome to My Morning Racket. Email: [email protected] Frequency: Weekly Release: Saturdays after 0900h Pacific Time Episode: 57 Original Air Date: May 10, 2019 Length: 118:00 Title: 90s Canadiana Host: Dave Del Rizzo Guests: 1 Rusty Fluke Wake Me 4.09 2 The Barenaked Ladies The Barenaked Ladies (Yellow Tape) Lovers in a Dangerous Time 4.11 3 The Lowest of the Low Shakespeare My Butt Henry Needs A New Pair of Shoes 3.44 4 Sloan Twice Removed People of the Sky 3.37 5 The Odds Bedbugs It Falls Apart 3.38 6 The Rheostatics Introducing Happiness Claire 4.08 7 Gandharvas A Soap Bubble and Inertia The First Day of Spring 4.24 8 I Mother Earth Scenery and Fish One More Astronaut 5.25 9 The Tea Party The Edges of Twilight Fire in the Head 5.05 10 The Tragically Hip Day For Night Nautical Disaster 4.43 11 Our Lady Peace Naveed Starseed 4.21 12 Moist Silver Push 3.50 13 Econoline Crush The Devil You Know Sparkle and Shine 3.41 14 The Age of Electric Make A Pest A Pet Remote Control 3.40 15 Limblifter Limblifter Vicious 3.10 16 Matthew Good Band Beautiful Midnight Hello Time Bomb 3.58 17 Spirit of the West Save This House Save This House 2.58 18 54-40 Smilin' Buddha Cabaret Blame Your Parents 4.27 19 Treble Charger NC17 Red 4.40 20 The Watchmen Brand New Day Incarnate 3.22 21 Bif Naked I Bificus Spaceman 4.22. -

CHRESTO MATHY the Poetry Issue

CHRESTO MATHY Chrestomathy (from the Greek words krestos, useful, and mathein, to know) is a collection of choice literary passages. In the study of literature, it is a type of reader or anthology that presents a sequence of example texts, selected to demonstrate the development of language or literary style The Poetry Issue TOYIA OJiH ODUTOLA WRITING FROM THE SEVENTH GRADE, 2019-2020 THE CALHOUN MIDDLE SCHOOL 1 SADIE HAWKINS Fairy Tale Poem I Am Poem Curses are fickle. You may have heard the story, I am loyal and trusting. Sleeping Beauty, I wonder what next and what now? The royal family births a child I hear songs that aren’t played, An event like this is to be remembered in joy by I see a world beyond ours, all. I want to travel. Yet it was spoiled, I am loyal and trusting, Why, you ask? I pretend to be part of the books I read. The parents, out of fear, made a fatal mistake. I feel happy and sad, They left out one guest. I touch soft fluff. One of the fairies of the forest, I worry about the future, The other three came, all but one. I cry over those lost. When it came for this time for the gifts it I am loyal and trusting happened. I understand things change, This is the story of Maleficent. I say they get better. This is my story. I dream for a better world, I try to understand those around me. It had come, I hope that things will improve, The birth of the heir I am loyal and trusting. -

Alternative 12748 Titel, 301:03:01:24 Gesamtlaufzeit, 55,38 GB

Alternative 12748 Titel, 301:03:01:24 Gesamtlaufzeit, 55,38 GB Interpret Album # Objekte Gesamtzeit A.F.I. Decemberunderground 13 48:34 Sing The Sorrow 14 1:03:37 Afro Celt Sound System Volume 2: Release 11 1:04:04 Albert King with Stevie Ray Vaughan In Session 11 1:03:54 Alice In Chains Alice In Chains 12 1:04:53 Dirt 13 57:35 Facelift 12 54:08 Jar Of Flies 7 30:52 The Allman Brothers Band A Decade Of Hits 1969-1979 16 1:15:52 Idlewild South 7 30:45 Shades Of Two Worlds 8 52:36 Alter Bridge Blackbird 13 59:16 One Day Remains 11 55:24 Amplifier Amplifier 14 1:21:50 Insider 12 59:05 Amy Winehouse Back To Black 11 34:58 Anarchy & Rapture The Lovers Enchained 1 5:27 Annwn Anarchy & Rapture 11 53:56 A Barroom Bransle 16 1:02:33 Come away to the Hills 14 1:07:20 The Lovers Enchained 13 1:02:39 Antichrisis Cantara Anachoreta 8 1:10:28 A Legacy of Love 10 1:10:10 Perfume 10 1:06:43 Antimatter Leaving Eden 9 47:45 Arena Contagion 16 58:49 Ark Burn the Sun 11 56:47 Army Of Anyone Army Of Anyone 9 38:32 Ascension Of The Watchers Numinosum 11 1:12:26 Audioslave Audioslave 14 1:05:27 Out Of Exile 12 53:44 Audiovent Dirty Sexy Knights In Paris 12 45:23 Automaniac Automaniac 10 47:13 Avril Lavigne Let Go 13 48:27 Aynsley Lister Everything I Need 10 52:26 Ayreon Actual Fantasy 9 1:02:21 The Human Equation 31 1:42:22 Into the Electric Castle 17 1:45:11 The Universal Migrator Part 1: The Dream Sequencer 11 1:10:35 The Universal Migrator Part 2: Flight Of The Migrator 8 57:20 B.R.M.C. -

Consensus Building Takes Priority Abortion

Thursday, September 14, 1995• Vol. XXVII No. 19 TilE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S • STUDENT SENATE • NEWS ANALYSIS Consensus building takes priority Abortion By GWENDOLYN NORGLE dent Body President Jonathan plish this year as a Senate?" "We have here a student law spurns Assistant Nc:ws Editor Patrick. "We're not as 'empowered' a leader from every major orga In a discussion of the roles body as the CLC," Patrick ex nization on campus. We could The Student and responsibilities of the Stu plained. "We need to utilize our be the most creative organiza questions Senate must dent Senate, Patrick presented voices a lot better than we have tion on campus. What we need his views of what these roles in the past." build consen to ask ourselves is 'Do we want By MARY KATE MORTON sus amongst are: the Senate is an organiza One way for the Senate to do to just be advisors all year?' We Associate Nc:ws Editor its members tion that advises and makes de that, he said, is to "better for would be so much more effec before pre cisions about the allocation of mulate our arguments and tive as students," Lawler said, Indiana Pro-Choicers are on senting issues runds. opinions before presenting "if we came (to CLC) with one the edges of their seats these to the admin "We're the only truly repre them." voice." days, and it looks like they will istration and sentative student body organi Student Union Board Manger Director of Student Activities stay that way for a while.