Hidden Trade Costs? Maximum Residue Limits and US Exports Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decision Guidance Documents

OPERATION OF THE PRIOR INFORMED CONSENT PROCEDURE FOR BANNED OR SEVERELY RESTRICTED CHEMICALS IN INTERNATIONAL TRADE DECISION GUIDANCE DOCUMENTS Methyl parathion (emulsifiable concentrates at or above 19.5% active ingredient and dusts at or above 1.5% active ingredient). JOINT FAO/UNEP PROGRAMME FOR THE OPERATION OF PRIOR INFORMED CONSENT United Nations Environment Programme UNEP Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations OPERATION OF THE PRIOR INFORMED CONSENT PROCEDURE FOR BANNED OR SEVERELY RESTRICTED CHEMICALS IN INTERNATIONAL TRADE DECISION GUIDANCE DOCUMENTS Methyl parathion (emulsifiable concentrates at or above 19.5% active ingredient and dusts at or above 1.5% active ingredient). JOINT FAO/UNEP PROGRAMME FOR THE OPERATION OF PRIOR INFORMED CONSENT Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations United Nations Environment Programme Rome - Geneva 1991; amended 1996 DISCLAIMER The inclusion of these chemicals in the Prior Informed Consent Procedure is based on reports of control action submitted to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) by participating countries, and which are presently listed in the UNEP-International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals (IRPTC) database on Prior Informed Consent. While recognizing that these reports from countries are subject to confirmation, the FAO/UNEP Joint Working Group of Experts on Prior Informed Consent has recommended that these chemicals be included in the Procedure. The status of these chemicals will be reconsidered on the basis of such new notifications as may be made by participating countries from time to time. The use of trade names in this document is primarily intended to facilitate the correct identification of the chemical. It is not intended to imply approval or disapproval of any particular company. -

Alinorm 01/24

E REP14/PR JOINT FAO/WHO FOOD STANDARDS PROGRAMME CODEX ALIMENTARIUS COMMISSION 37th Session Geneva, Switzerland, 14 – 18 July 2014 REPORT OF THE 46th SESSION OF THE CODEX COMMITTEE ON PESTICIDE RESIDUES Nanjing, China, 5 - 10 May 2014 Note: This report includes Codex Circular Letter CL 2014/16-PR. E CX 4/40.2 CL 2014/16-PR May 2014 To: - Codex Contact Points - Interested International Organizations From: Secretariat, Codex Alimentarius Commission, Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme, E-mail: [email protected], Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy SUBJECT: DISTRIBUTION OF THE REPORT OF THE 46TH SESSION OF THE CODEX COMMITTEE ON PESTICIDE RESIDUES (REP14/PR) The report of the 46th Session of the Codex Committee on Pesticide Residues will be considered by the 37th Session of the Codex Alimentarius Commission (Geneva, Switzerland, 14 – 18 July 2014). PART A: MATTERS FOR ADOPTION BY THE 37TH SESSION OF THE CODEX ALIMENTARIUS COMMISSION: 1. Draft maximum residue limits for pesticides at Step 8 (para 115, Appendix II). 2. Proposed draft maximum residue limits for pesticides at Step 5/8 (with omission of Steps 6/7) (para 115, Appendix III). 3. Proposed draft revision to the Classification of Food and Feed at Step 5 – selected vegetable commodity groups (Group 015 - Pulses) (para 148, Appendix X). 4. Revised Risk Analysis Principles applied by the Codex Committee on Pesticide Residues (para 163, Appendix XIII). Governments and international organizations wishing to submit comments on the above matters, should do so in writing, in conformity with the Procedure for the Elaboration of Codex Standards and Related Texts (Part 3 – Uniform Procedure for the Elaboration of Codex Standards and Related Texts, Procedural Manual of the Codex Alimentarius Commission) by e-mail, to the above address before 20 June 2014. -

Glyphosate: Unsafe on Any Plate

GLYPHOSATE: UNSAFE ON ANY PLATE ALARMING LEVELS OF MONSANTO’S GLYPHOSATE FOUND IN POPULAR AMERICAN FOODS “For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals from the moment of conception until death…These chemicals are now stored in the bodies of the vast majority of human beings, regardless of age. They occur in the mother’s milk, and probably in the tissues of the unborn child.”1 —RACHEL CARSON, SILENT SPRING “Glyphosate was significantly higher in humans [fed] conventional [food] compared with predominantly organic [fed] humans. Also the glyphosate residues in urine were grouped according to the human health status. Chronically ill humans had significantly higher glyphosate residues in urine than healthy humans”2 —MONIKA KRUGER, ENVIRONMENTAL & ANALYTICAL TOXICOLOGY “Analysis of individual tissues demonstrated that bone contained the highest concentration of [14C] glyphosate equivalents (0.3–31ppm). The remaining tissues contained glyphosate equivalents at a concentration of between 0.0003 and 11 ppm. In the bone and some highly perfused tissues, levels were statistically higher in males than in females.”3 —PESTICIDE RESIDUES IN FOOD, JOINT FAO/WHO MEETING 2004 1 Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, (Houghton Mifflin, 1961), Elixirs of Death, 15-16. 2 Krüger M, Schledorn P, Schrödl W, Hoppe HW, Lutz W, et al. (2014) Detection of Glyphosate Residues in Animals and Humans. J Environ Anal Toxicol 4: 210 3 Residues in Food, 2004, Evaluations Part II, Toxicological, Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues. http://apps.who.int/iris/ bitstream/10665/43624/1/9241665203_eng.pdf Contents What Is in This Report? Findings: The first ever independent, FDA-registered laboratory food testing results for glyphosate residues in iconic American food brands finds alarming levels of glyphosate contamination and reveal the inadequacy of current food safety regulations relating to allowable pesticide residues. -

Dietary Supplements Stakeholder Forum Michael Mcguffin, Chair Summary Discussions Wednesday, June 1, 2016

Dietary Supplements Stakeholder Forum Michael McGuffin, Chair Summary Discussions Wednesday, June 1, 2016 What We Heard USP Updates and Discussions—Adulterants Database Stakeholders —consumers, marketers, regulators—will work together to solve the problem caused by adulterated products that masquerade as dietary supplements (DSs). USP should make more clear that tools to detect adulteration by drug spiking are not meant as standards for manufacturers, but rather as tests for regulators in enforcement/forensic actions. There is sensitivity in the industry about screening methods being required as regular tests for GMP compliance. The adulterants database was well received, but stakeholders emphasized that adulteration by ingredient substitution, dilution, and spiking with botanical chemical markers are areas more relevant for the manufacturers than adulteration by drug spiking. 2 What We Heard USP Updates and Discussions—Adulterants Database USP must make the planned database comprehensible, segregating the drug/drug analog tainted products of interest to regulators from the economically motivated adulteration of interest to dietary supplement ingredient purchasers. – Confusion can arise because the adulterants database is perceived as a tool for industry, but in reality it is a tool for regulators, enforcement agencies and forensic laboratories. – Separate section on authentication would highlight the function of the database as a product and ingredient integrity tool manufacturers can use to protect themselves against Economically Motivated Adulteration. Action Item: Attendees interested in participating in beta-testing the USP database will contact Mr. Anton Bzhelyansky ([email protected]). 3 What We Heard USP Updates and Discussions—DNA-based Methods for Botanical Identification DNA testing is an emerging tool of indisputable value. -

Pesticide Residues : Maximum Residue Limits

THAI AGRICULTURAL STANDARD TAS 9002-2013 PESTICIDE RESIDUES : MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives ICS 67.040 ISBN UNOFFICAL TRANSLATION THAI AGRICULTURAL STANDARD TAS 9002-2013 PESTICIDE RESIDUES : MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives 50 Phaholyothin Road, Ladyao, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900 Telephone (662) 561 2277 Fascimile: (662) 561 3357 www.acfs.go.th Published in the Royal Gazette, Announcement and General Publication Volume 131, Special Section 32ง (Ngo), Dated 13 February B.E. 2557 (2014) (2) Technical Committee on the Elaboration of the Thai Agricultural Standard on Maximum Residue Limits for Pesticide 1. Mrs. Manthana Milne Chairperson Department of Agriculture 2. Mrs. Thanida Harintharanon Member Department of Livestock Development 3. Mrs. Kanokporn Atisook Member Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health 4. Mrs. Chuensuke Methakulawat Member Office of the Consumer Protection Board, The Prime Minister’s Office 5. Ms. Warunee Sensupa Member Food and Drug Administration, Ministry of Public Health 6. Mr. Thammanoon Kaewkhongkha Member Office of Agricultural Regulation, Department of Agriculture 7. Mr. Pisan Pongsapitch Member National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards 8. Ms. Wipa Thangnipon Member Office of Agricultural Production Science Research and Development, Department of Agriculture 9. Ms. Pojjanee Paniangvait Member Board of Trade of Thailand 10. Mr. Charoen Kaowsuksai Member Food Processing Industry Club, Federation of Thai Industries 11. Ms. Natchaya Chumsawat Member Thai Agro Business Association 12. Mr. Sinchai Swasdichai Member Thai Crop Protection Association 13. Mrs. Nuansri Tayaputch Member Expert on Method of Analysis 14. -

Evaluation of Different Models for Non-Destructive Detection of Tomato Pesticide Residues Based on Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

sensors Article Evaluation of Different Models for Non-Destructive Detection of Tomato Pesticide Residues Based on Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Araz Soltani Nazarloo 1 , Vali Rasooli Sharabiani 1,* , Yousef Abbaspour Gilandeh 1 , Ebrahim Taghinezhad 2 and Mariusz Szymanek 3 1 Department of Biosystem Engineering, Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil 56199-11367, Iran; [email protected] (A.S.N.); [email protected] (Y.A.G.) 2 Department of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, Moghan College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil 56199-11367, Iran; [email protected] 3 Department of Agricultural, Forest and Transport Machinery, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Street Gł˛eboka28, 20-612 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +98-914-451-9089 Abstract: In this study, the possibility of non-destructive detection of tomato pesticide residues was investigated using Vis/NIRS and prediction models such as PLSR and ANN. First, Vis/NIR spectral data from 180 samples of non-pesticide tomatoes (used as a control treatment) and samples impregnated with pesticide with a concentration of 2 L per 1000 L between 350–1100 nm were recorded by a spectroradiometer. Then, they were divided into two parts: Calibration data (70%) and prediction data (30%). Next, the prediction performance of PLSR and ANN models after processing was compared with 10 spectral preprocessing methods. Spectral data obtained from spectroscopy Citation: Nazarloo, A.S.; Sharabiani, were used as input and pesticide values obtained by gas chromatography method were used as V.R.; Gilandeh, Y.A.; Taghinezhad, E.; output data. -

The Presence of Organochlorine Pesticide Residues in Milk, Meat, Liver, and Kidney in Jordan Cattle

Sys Rev Pharm 2020;11(11):1491-1495 A multifaceted review journal in the field of pharmacy Banned Organochlorine Pesticides Still in Our Food: The Presence of Organochlorine Pesticide Residues in Milk, Meat, Liver, and Kidney in Jordan Cattle Jehad S. Al-Hawadi Ash-Shoubak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Al Salt 19117, Jordan Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT To assess the potential risks posed by residual organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) to Keywords: Organochlorine; pesticide residues; cow; milk; meat; liver; kidney; human health, we evaluated the consumption of animal products as the primary Jordan route of human exposure to these compounds. In this study, 120 samples of milk, meat, and edible tissues (liver and kidney) were collected from farms and Correspondence: slaughterhouses in Amman, Jordan. Fifteen OCPs, including Jehad S. Al-Hawadi dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its metabolites, Ash-Shoubak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Al Salt 19117, hexachlorocyclohexane isomers (HCHs), aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, Jordan heptachlor epoxide, and hexachlorobenzene (HCB), were identified and further investigated. These samples were extracted using the Soxhlet method, subjected Email: [email protected] to Florisil column chromatography, and analyzed using gas chromatography with an electron capture detector (GC–ECD). The results revealed that 40%, 40%, 46.7%, and 33.3% of the examined milk, meat, liver, and kidney samples, respectively, were contaminated with OCPs. This study confirmed that residual OCPs persist in cow-derived food products in Jordan. INTRODUCTION chemicals [9]. OCPs including DDT, HCB, and An increase in global food demand, especially in hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) are classified in group 2B developing countries experiencing population increases, (carcinogenic in humans) according to the International has led to extensive use of agrochemicals to enhance food Agency for Research on Cancer [10,11]. -

Comparison of Sin-Quechers Nano and D-SPE Methods for Pesticide Multi-Residues in Lettuce and Chinese Chives

molecules Article Comparison of Sin-QuEChERS Nano and d-SPE Methods for Pesticide Multi-Residues in Lettuce and Chinese Chives Yanjie Li 1 , Quanshun An 2, Changpeng Zhang 1, Canping Pan 2,* and Zhiheng Zhang 1,* 1 Institute of Quality and Standard for Agro-Products, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou 310021, China; [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (C.Z.) 2 Department of Applied Chemistry, College of Science, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100193, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (Z.Z.); Tel.: +86-10-62731978 (C.P.); +86-571-86419053 (Z.Z.) Received: 28 June 2020; Accepted: 22 July 2020; Published: 27 July 2020 Abstract: In this study, a new rapid cleanup method was developed for the analysis of 111 pesticide multi-residues in lettuce and Chinese chives by GC–MS/MS and LC–MS/MS. QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged and safe)-based sample extraction was used to obtain the extracts, and the cleanup procedure was carried out using a Sin-QuEChERS nano cartridge. Comparison of the cleanup effects, limits of quantification and limits of detection, recoveries, precision and matrix effects (MEs) between the Sin-QuEChERS nano method and the classical dispersive solid phase extraction (d-SPE) method were performed. When spiked at 10 and 100 µg/kg, the number of pesticides with recoveries between 90% to 110% and relative standard deviations < 15% were greater when using the Sin-QuEChERS nano method. The MEs of Sin-QuEChERS nano and d-SPE methods ranged between 0.72 to 3.41 and 0.63 to 3.56, respectively. -

Draft for Consultation

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION PEST AND PESTICIDE MANAGEMENT What is it about: Pests include all the diseases, insects, weeds and rodents that can cause damage to growing crops. Pest management refers to all the methods that can be used to manage pests and their impacts. For example, farmers can use strategies that combine preventive and corrective methods/tools to reduce pests to acceptable levels. Specifically, an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy will be based on taking preventive measures, monitoring the crop or site for the level of the pest(s), assessing the potential threshold for pest damage, and choosing appropriate actions if necessary. Pesticides are products that growers can use to reduce crop damage due to pests. There are three main categories of pesticides used in crop production: • Herbicides are used to control unwanted plants • Insecticides are used to control insects • Fungicides are used to control plant diseases Why is it important: Pesticides help farmers protect their crops from damage due to weeds, insects and disease, and make it possible to produce a greater quantity, higher quality and diversity of crops on existing farmland. Pesticides must be used properly to protect human health and the environment. Why is it in the Code: Pesticides are regulated in Canada, from manufacture, import, sale, transport, storage and responsible use through to application and safe disposal. Both federal and provincial governments play a role in this regulation. • Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (via the Pest Control Products Act (PCPA)) controls the registration of pest control products to be used, sold, manufactured, stored or imported into Canada and the approval of pesticide labels. -

Principles and Methods for the Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food

IPCS INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME ON CHEMICAL SAFETY ILO UNEP Environmental Health Criteria 240 Principles and Methods for the Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food Chapter 8 MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS FOR PESTICIDES AND VETERINARY DRUGS A joint publication of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organization or the World Health Organization. Environmental Health Criteria 240 PRINCIPLES AND METHODS FOR THE RISK ASSESSMENT OF CHEMICALS IN FOOD A joint publication of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organization and the World Health Organization, and produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals. Food and Agriculture F S Organization of the I I A N T PA United Nations The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), established in 1980, is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). The overall objec tives of the IPCS are to establish the scientific basis for assessment of the risk to human health and the environment from exposure to chemicals, through international peer review processes, as a prerequisite for the promotion of chemical safety, and to provide technical assistance in strengthening national capacities for the sound management of chemicals. -

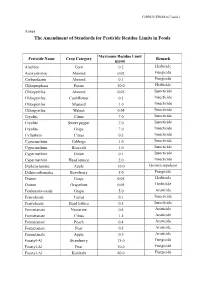

The Amendment of Standards for Pesticide Residue Limits in Foods

G/SPS/N/TPKM/167/Add.1 Annex The Amendment of Standards for Pesticide Residue Limits in Foods Maximum Residue Limit Pesticide Name Crop Category Remark (ppm) Alachlor Corn 0.2 Herbicide Azoxystrobin Almond 0.02 Fungicide Carbendazim Almond 0.1 Fungicide Chlorpropham Potato 30.0 Herbicide Chlorpyrifos Almond 0.05 Insecticide Chlorpyrifos Cauliflower 0.5 Insecticide Chlorpyrifos Mustard 1.0 Insecticide Chlorpyrifos Walnut 0.05 Insecticide Cryolite Citrus 7.0 Insecticide Cryolite Sweet pepper 7.0 Insecticide Cryolite Grape 7.0 Insecticide Cyfluthrin Citrus 0.3 Insecticide Cypermethrin Cabbage 1.0 Insecticide Cypermethrin Broccoli 1.0 Insecticide Cypermethrin Onion 0.1 Insecticide Cypermethrin Head lettuce 2.0 Insecticide Diphenylamine Apple 10.0 Growth regulator Dithiocarbamates Strawberry 5.0 Fungicide Diuron Grape 0.05 Herbicide Diuron Grapefruit 0.05 Herbicide Fenbutatin-oxide Grape 5.0 Acaricide Fenvalerate Carrot 0.1 Insecticide Fenvalerate Head lettuce 0.5 Insecticide Formetanate Nectarine 0.4 Acaricide Formetanate Citrus 1.5 Acaricide Formetanate Peach 0.4 Acaricide Formetanate Pear 0.5 Acaricide Formetanate Apple 0.5 Acaricide Fosetyl-Al Strawberry 75.0 Fungicide Fosetyl-Al Pear 10.0 Fungicide Fosetyl-Al Kohlrabi 60.0 Fungicide G/SPS/N/TPKM/167/Add.1 Fosetyl-Al Kale 60.0 Fungicide Fosetyl-Al Head lettuce 100.0 Fungicide Fosetyl-Al Asparagus 0.1 Fungicide Fosetyl-Al Apple 10.0 Fungicide Hexythiazox Peach 1.0 Acaricide Imidacloprid Apple 0.5 Insecticide Imidacloprid Head lettuce 2.0 Insecticide Imidacloprid Sweet pepper 1.0 Insecticide -

Report Name:China Releases Draft Standard for Mrls of Pesticides In

Voluntary Report – Voluntary - Public Distribution Date: December 14,2020 Report Number: CH2020-0164 Report Name: China Releases Draft Standard for MRLs of Pesticides in Food Country: China - Peoples Republic of Post: Beijing Report Category: Avocado, Canned Deciduous Fruit, Dried Fruit, Fresh Deciduous Fruit, Fresh Fruit, Kiwifruit, Raisins, Stone Fruit, Strawberries, Sanitary/Phytosanitary/Food Safety, FAIRS Subject Report Prepared By: FAS Beijing Staff Approved By: Adam Branson Report Highlights: On November 23, 2020, the Crop Production Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) released for domestic comment the draft national food safety standard Maximum Residue Limits of 75 Pesticides (including 2,4-D-dimethylamine) in Foods. The draft standard provides 212 maximum residue limits (MRLs) for 75 pesticides in a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains, oilseeds, and plant-based beverages. China is expected to notify the draft MRLs to the WTO SPS Committee following the domestic comment period. Comments can be sent to the Secretariat of the National Committee of Pesticide Residue Limit Standards at [email protected]. The comment deadline is December 22, 2020. This report contains an unofficial translation of the draft standard. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY BEGIN TRANSLATION National Food Safety Standard Maximum Residue Limits for 75 Pesticides in Food1 (Draft for Comments) Table of Contents 1.Scope.......................................................................................................................................................