Advancing Opportunity: New Models of Schooling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Comprehensive Education: an Interview with Clyde Chitty

FORUM Volume 59, Number 3, 2017 www.wwwords.co.uk/FORUM http://dx.doi.org/10.15730/forum.2017.59.3.309 The ‘Patron Saint’ of Comprehensive Education: an interview with Clyde Chitty. Part One MELISSA BENN & JANE MARTIN ABSTRACT FORUM invited Melissa Benn and Jane Martin to interview Clyde Chitty, a brilliant and effective classroom and university teacher, one of the most well-known advocates of comprehensive education, a long-standing member of FORUM’s editorial board, and for two decades co-editor of the publication. It was Michael Armstrong who called him ‘the patron saint of the movement for comprehensive education’, in a card written to Clyde when he stepped away from regular duties with the FORUM board. In three 45-minute interviews, conducted at Clyde’s home, Clyde shared reflections with us on a working life as a teacher-researcher who notably campaigned for the universal provision of comprehensive state education. In this article, which comprises Part One of the interviews (Part Two will appear in the spring 2018 number of FORUM), Clyde’s unshakeable conviction that education has the power to enhance the lives of all is illustrated by plentiful examples from his work-life history. Clyde Chitty grew up in London just after the Second World War during the glory days of radio, for which he remains nostalgic. As a child, he loved all the popular series on Children’s Hour and other familiar programmes such as ‘Dick Barton – Special Agent’, and he is still a huge fan of ‘The Archers’. Clyde passed his 11-plus and was educated at a single-sex direct grant grammar school in Hammersmith between 1955 and 1962. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton Richardson, Martin Howard How to cite: Richardson, Martin Howard (1998) The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN COUNTY DURHAM, 1944-1974, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FERRYHILL AND CHILTON MARTIN HOWARD RICHARDSON This thesis grew out of a single question: why should a staunch Labour Party stronghold like County Durham open a grammar school in 1964 when the national Party was so firmly committed to comprehensivization? The answer was less easy to find than the question was to pose. -

Ivybridge Community College Jubilee 1958 – 2019 EDUCATIONAL

Ivybridge Community College Jubilee 1958 – 2019 EDUCATIONAL CHANGE 1958 Headteacher: Mr K A Baker White Paper Secondary Education for All: A New Drive (December) 1958 announced a £300m school building programme consisting mostly of new secondary modern schools 1959 Education Act (July) 1959 Minister of Education ‘to make contributions, grants and loans in respect of aided schools and special agreement schools’ Secondary School Examinations other than the GCE (July) Report of the Committee appointed by the Secondary School 1960 Examinations Council which led to the introduction of Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) in 1965 Education Act (March) Placed legal obligation on parents to ensure that children received a 1962 suitable education at school or otherwise. Local Education Authorities legally responsible for ensuring that pupils attend school 1963 Robin Pedley The Comprehensive School – reprinted many times Ministry of Education reorganised as the Department of Education and 1964 Science 1964 Education Act (July) 1964 Allowed the creation of middle schools 1965 Bachelor of Education (Bed) courses begin Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) introduced in England and 1965 Wales 1967 The Plowden Report - Children and their Primary Schools (January) Margaret Thatcher appointed Shadow Secretary of State for Education 1967 (January) 1968 Education Act (July) 1968 laid down rules about changing the character of a school (for example to a comprehensive) School Meals Agreement 1968 Teachers were no longer obliged to supervise children -

Download (514Kb)

Inclusion, Cultural Diversity and Schooling I The first thing I should say, before I say anything about inclusion, the curriculum and the pupil experience, because this is more than just about the classroom, is thank you for everything you will go on to do in stimulating teaching and learning in schools and elsewhere. That ‘thank you’ for what you will do in the future is partly in the knowledge that you, as a body of people will go on to do great things – as it is clear that people in this room have the ability to make a difference to many, many thousands of people’s lives. And, it is also partly a reminder that you should think yourself as duty-bound to do so. What is today about? Inclusion. Where should I begin? We are not born equal; neither do we live in equal circumstances, and both of these heavily influence our potential in relation to our educational outcomes and even our lifespan. These are the unsurprising headlines from two very recent surveys. One survey suggests that the social class into which we are born influences our potential lifespan – both boys and girls born today into classes A and B can expect to live into their eighties, almost ten percent longer than those born into social class C. The presence, absence or role of parents can also be very influential; and research published only last November about pupils living in care tells us that their GCSE results - an easy, if not necessarily the only significant measure of success – are as poor as they can get for an identifiable group in society. -

The Development of Secondary Education in County Durham, 1944-1974, with Special Reference to Ferryhill and Chilton

Durham E-Theses The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton Richardson, Martin Howard How to cite: Richardson, Martin Howard (1998) The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN COUNTY DURHAM, 1944-1974, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FERRYHILL AND CHILTON MARTIN HOWARD RICHARDSON This thesis grew out of a single question: why should a staunch Labour Party stronghold like County Durham open a grammar school in 1964 when the national Party was so firmly committed to comprehensivization? The answer was less easy to find than the question was to pose. -

The Story of FORUM, 1958-2008

FORUM Volume 50, Number 3, 2008 www.wwwords.co.uk/FORUM EDITORIAL The Story of FORUM, 1958-2008 CLYDE CHITTY How FORUM began The spring of 1957 saw the publication of a collection of essays edited by Brian Simon, a lecturer in education at Leicester University, looking at changes that had taken place both in the school system generally and within individual schools in the decade or so since the passing of the 1944 Education Act, and with the title New Trends in English Education. The timing of the book’s publication was propitious, in that the mid-1950s was a period of really exciting new developments in the education system of England and Wales, with the opening of Kidbrooke School, London’s first new purpose-built comprehensive, in the autumn of 1954; the launch of the two-tier Leicestershire Plan for comprehensive reorganisation (very much the brainchild of Brian’s colleague Robin Pedley) in 1957; and the publication, also in 1957, of a report by the British Psychological Society questioning (albeit tentatively) the validity of Cyril Burt’s theories about fixed innate intelligence. The ‘trends’ identified in the 1957 book could be summarised under four main headings: (1) the abolition of A, B and C streams at the junior school stage in favour of a common basic course at the outset of school life; (2) the entry of secondary modern school pupils for external examinations, which showed that some could reach a standard of achievement as high as, or higher than, many grammar school pupils; (3) the introduction of comprehensive schools, a number of which had now been successfully operating for a decade, and which, if generally established, would make eleven-plus selection unnecessary; 281 Editorial (4) the evolution towards a common curriculum within the new comprehensive school which pointed the way to a well-balanced general education for all at the secondary stage. -

RISINGHILL REVISITED – Book 2

RISINGHILL REVISITED – Book 2 The Waste Clay The Risinghill Research Group Isabel Sheridan, Philip Lord, Lynn Brady, Alan Foxall, John Bailey and Yvonne Fisher ‘Such were the joys When we all girls & boys In our youth time were seen On the Ecchoing Green.’ William Blake, From ’The Ecchoing Green, Songs of Innocence and Experience’ 319 Dedication This book is dedicated to the Risinghill teachers and pupils, in particular those who have participated in the research for Risinghill Revisited (RR): without their contributions The Waste Clay would not have been possible. Leila Berg, author of Risinghill: death of a Comprehensive School is also acknowledged here – for providing the authors with so much background information to the writing of her book, and for producing a piece (entitled ‘The Next Room’) for inclusion in The Waste Clay. The authors hope that RR will serve to keep their memories alive, and indeed the memories of all who have fought for an education system in which every child truly matters. 320 Disclaimer Although the authors and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at time of going to press, the authors in whose hands all responsibility for any concerns and their solutions rests, do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals. Where names are not changed full permissions to include such names has been received by the authors and the responsibility for any errors in this respect lies solely with the authors. -

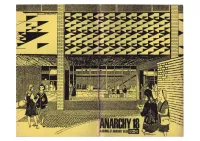

Anarchy No. 18

Contents of No. 18 August 1962 225 A correspondent Comprehensive schools 225 in The Observer a short time ago concluded his letter thus: 'The Fairy Tale Education Educating the non-scholastic H. Raymond King 233 of runs as follows: Once upon a time God made three types of children. The Nor- Bombed site and comprehensive school Winifred Hindley 238 wood Report discovered what they were. The Ministry put A last look round Sixth-Former 242 them neatly in different schools. And they all lived unhappily ever Some were ail right Early Leaver 243 after.' We in the comprehensive school believe that there are as First impression First-Former 245 many different types of child as there are children, and that it is comprehensive Parent 246 Eleven-plus and the not our job in education to iron out the differences and produce concert of the high school of music and art Paul Goodman 248 one standard A senior product or three standard products fust because it Down there with Isherwood Dachine Rainer 251 is administratively convenient and suits the haphazard historical The anarchists from outside Nicholas Barman 256 development of our educational system. of Hurlingham Cover: from a drawing by Kenneth Browne School ~G. A. Rogers, Headmaster of Walworth School, London. Partners). Fulham (Architects : Richard Sheppard and Other issues of ANARCHY Acknowledgements 1. Sex-and-VioIence; Galbraith; We are grateful to Mr. King and the New Wave, Education, Mrs. Hindley, and the the editors of Opportunity, Equality. Forum: for the discussion of new trends in education and of Athene, 2. Workers' Control. -

1 'Britain Is Watching This School Experiment, Anglesey Leads the Way'

1 ‘Britain is watching this school experiment, Anglesey leads the way’. A forgotten pioneer? Anglesey’s comprehensive system, circa 1953-1970. Anglesey was a prominent pioneer of comprehensive education in the 1950s and 1960s. Despite this, however, if you were to discuss comprehensive schooling and education with somebody today, it is highly unlikely that they would be aware of the fact that the first fully comprehensive scheme in England and Wales was introduced on Anglesey as early as 1953. While a handful of Local Education Authorities (LEAs) had established isolated comprehensive schools prior to this (in fact the secondary school in Holyhead was officially reorganised into a comprehensive in 1949), no other LEA had thus far introduced a fully comprehensive system of secondary education. However, once the county’s four secondary schools had been turned into comprehensives, Anglesey did indeed become the first ever pioneer of a fully comprehensive system in England and Wales.1 Despite Anglesey’s prominence in the field of secondary school reform, minimal interest has been paid to these developments in existing scholarship.2 In light of this, the key objective of this article is to emphasise the role which Anglesey played in the field of comprehensive schooling, and to illustrate its place within the wider historiography. The main argument here is that the exclusion of early pioneers of comprehensive schooling, such as Anglesey, from the historiography has resulted 1 The Isle of Man had in fact introduced a comprehensive system by this time as well, however, due to its exceptional autonomy from the rest of Britain it was outside the influence of the Ministry of Education. -

The British Comprehensive Secondary School

The British Comprehensive Secondary School: An Instrument for Social Reform? Robert M. Martin During the past two decades an evolution has been in industrial cities like Bristol, Coventry, and London, taking place in British education. And nowhere is that more where a combination of extensive war damage lo existing evident than at the secondary school level. Herc the com school buildings, and the presence of Labour Party Councils prehensive-type school has been assuming configuration have been additional causative factors. The nine schools with clear-cut functions. An examination of this educa visited were: Ca1tlc Rushen School, Castletown, Isle of tional structure, so familiar to us, but new to British Man; Ruffwood School, Kirkby Estate, Lancashire; Sir schoolmcn and children can prove illuminating. Thomas Jones School, Amlwch, Anglesey, Wales; Church During the 1968-69 school year, tl1e writer visited nine fields School, West Bromwich, Birmingham; President schools recommended by the British Ministry of Educa Kennedy School, Coventry; Henbury School. Bristol; tion's Department of Education and Science as represen Alfred Col/ox School, Bridport, Dorset; Thomas Bennett tative of the better comprehensive schools in Great Britain. School, Crawley, West Sussex; Wandsworth School, South· He came away with some deep and favorable impressions. fields Borough, London. 9 Two features, in fact, might serve as subjects for study by American educators with comparable procedures in our Background of the British own comprehensive secondary schools. First is the vertical Comprehensive Secondary School organization within each British school of sub-groups for American educators should not assume that the British educational, social and guidance direction. -

Appendix the Present Structure of Post -Compulsory Education

APPENDIX THE PRESENT STRUCTURE OF POST -COMPULSORY EDUCATION 16 to 18 (See also Chapter 2) Compulsory schooling was extended from age 15 to 16 in 1972-3. Most full-time education 16-18 is provided in school sixth forms which mainly offer academic courses (at G.C.E. 'A' level) leading to higher education, although provision is increasingly being made for less able students and for those who want commercial and other vocational but non-technical courses. The chief alternative sources of full-time education (for about 30 per cent of the full-time students aged 16-18) are the colleges of further education, often still called technical colleges, which provide for students of any age beyond 16, academic courses to 'A' and '0' level, plus a wide range of vocational courses in such areas as technical studies, commerce and design. The most important development in the 1970s is the appear ance of tertiary colleges: colleges of further education which take in all the full-time students over 16 who formerly stayed at school in the sixth form. Although there were only ten (scat tered among six local education authorities) in September 1976, both the Secretary of State for Education and Science and the Permanent Secretary of D.E.S. early in 1977 declared their interest in this third stage in the development of a compre hensive system. 'fhere are, however, three chief obstacles to the emergence of tertiary colleges as the basis for the next stage in comprehensive reorganisation: 94 Appendix 95 UPPER SECONDARY, FURTHER AND HIGHER EDUCATION TODAY THE PUBLIC SECTOR THE (administered by LEAs.' (.II'- apart from a small AUTONOMOUS number of independent SECTOR schools and voluntary collegeslinstitutes of I I FURTHER FURTHER POLYTECHNIC COLLEGEI UNIVERSITY education/higher EDUCATION EDUCATION (mainly INSTITUTE (mainly education) COLLEGE (TERTIARYI advanced OF _need cour.for (mainly COLLEGE cour. -

The Personal Tutor and Tutees' Encounters of the Personal Tutor Role- Their Lived Experiences

The Personal Tutor and Tutees' Encounters of the Personal Tutor Role- Their lived Experiences A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Anjoti Harrington School of Sport & Education BruneI University September 2004 Book one Abstract The study investigated the relationship between personal tutor and tutee, perceptions of support encounters and their lived experiences within an undergraduate pre registration nurse education programme. The personal tutoring system plays a vital role in sustaining nurse learners by being an anchor for their professional and personal development. The tutors monitor progress, support, intervene on the tutees' behalf and act as a confidante. The need for support is especially acute in university based nurse education when the tutees face challenges in clinical practice due to the vocational and professional nature of the course they are undertaking. Yet the meaning of the personal tutoring role is often confusing and serious misunderstandings may exist between tutors and tutees. The aim of this study is to search for the meamng of personal tutoring by illuminating their lived expenences and encounters. An 'Husserlian' phenomenological approach was taken. A purposive sample of 36 tutors and 44 tutees (9 tutors and 10 tutees were from a Northern university and 27 tutors and 34 tutees from a London university) took part in the study. Each of their experiences were recorded in a 30-45 minutes open-ended taped interview. The findings were analysed by Colaizzi's (1978); Van Manen's (1990) and Cortazzi's (1993) data analysis methods. The findings revealed a wide variation of encounters on the nature of support and practice.