Epilogue Craig Campbell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selective High School 2021 Application

Stages of the placement process High Performing Students Team Parents read the application information online From mid-September 2019 Education Parents register, receive a password, log in, and then completeApplying and submit for the application Year online7 entry From 8 to selective high schools October 2019 to 11 November 2019 Parents request any disability provisions from 8 October to in 11 November 2019 2021 Principals provide school assessment scores From 19 November to Thinking7 December 2019 of applying for Key Dates Parents sent ‘Test authority’ letter On 27 Febru- ary 2020 a government selective Application website opens: Students sit the Selective High School 8 October 2019 Placementhigh Test forschool entry to Year 7for in 2021 Year On 12 7 March 2020 Any illness/misadventurein 2021?requests are submitted Application website closes: By 26 March 2020 10 pm, 11 November 2019 You must apply before this deadline. Last dayYou to change must selective apply high school online choices at: 26 April 2020 School selectioneducation.nsw.gov.au/public- committees meet In May and Test authority advice sent to all applicants: June 2020 27 February 2020 Placementschools/selective-high-schools- outcome sent to parents Overnight on 4 July and-opportunity-classes/year-7 Selective High School placement test: 2020 12 March 2020 Parents submit any appeals to principals By 22 July 2020 12 Parents accept or decline offers From Placement outcome information sent overnight on: July 2020 to at least the end of Term 1 2021 4 July 2020 13 Students who have accepted offers are with- drawn from reserve lists At 3 pm on 16 December 2020 14 Parents of successful students receive ‘Author- Please read this booklet carefully before applying. -

Hitler's Pope

1ews• Hitler's Pope Since last Christmas, GOOD SHEPHERD has assisted: - 103 homeless people to find permanent accommodation; - 70 young people to find foster care; - 7S7 families to receive financial counselling; - 21 9 people through a No Interest Loan (N ILS); Art Monthly - 12 adolescent mothers to find a place to live with support; .-lUSTR .-l/,/. 1 - 43 single mothers escaping domestic violence to find a safe home for their families; - 1466 adolescent s through counselling: - 662 young women and their families, I :\' T H E N 0 , . E '1 B E R I S S L E through counsell ing work and Reiki; - hundreds of families and Patrick I lutching;s rC\ie\\s the Jeffrey Smart retruspecti\e individuals through referrals, by speaking out against injustices and by advocating :\mire\\ Sa\ ers talks to I )a\ id I lockney <lhout portraiture on their behalf. Sunnne Spunn~:r trac~:s tht: )!t:nt:alo g;y of the Tclstra \:ational .\horig;inal and Torres Strait Islander :\rt .\"ani \bry Eag;k rt:\it:\\S the conti:rmct: \\'hat John lkrg;t:r Sa\\ Christopher I leathcott: on Australian artists and em ironm~:ntal awart:nt:ss Out now S-1. 1/'i, ji·ll/1/ g lllld 1/(/llhl/llf>S 111/d 1/ t' II ' S i /. ~t' II/S. Or plulllt' IJl fJl.J'J .i'JSfJ ji1 r your su/>stnf>/11111 AUSTRALIAN "Everyone said they wanted a full church. What I discovered was that whil e that was true, they di dn't BOOK REVIEW want any new people. -

Corporatised Universities: an Educational and Cultural Disaster

John Biggs and Richard Davis (eds), The Subversion of Australian Universities (Wollongong: Fund for Intellectual Dissent, 2002). Chapter 12 Corporatised universities: an educational and cultural disaster John Biggs Where from here? Australian universities have been heavily criticised in these pages, and some specific examples of where things have gone wrong have been reported in detail. Not everyone sees these events negatively, how- ever. Professor Don Aitken, until recently Vice-Chancellor of the University of Canberra, said: I remain optimistic about the future of higher education in Australia. … To regard what is happening to universities in Australia as simply the work of misguided politicians or managers is abysmally paro- chial.1 Are the authors in this book concentrating too much on the damage that has been done? Is a greater good emerging that we have missed so far? As was pointed out in the Preface, globalisation is upon us; it is less than helpful to command, Canute-like, the tide to retreat. Rather the wise thing would be to acknowledge what we cannot change, and focus on what we can change. At the least, we need a resolution that is more academically acceptable than the one we have. The Vice-Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh, Professor Stuart Sutherland, in commenting on parallel changes in Britain, put it this way: 185 The subversion of Australian universities The most critical task for universities is to recreate a sense of our own worth by refashioning our understanding of our identity — our under- standing of what the word “university” means. …The trouble is that in the process of expansion and diversification, the place that universities had at the table has not simply been redefined; it has been lost.2 Australian universities too have lost their place at the table. -

Of Comprehensive Education: an Interview with Clyde Chitty

FORUM Volume 59, Number 3, 2017 www.wwwords.co.uk/FORUM http://dx.doi.org/10.15730/forum.2017.59.3.309 The ‘Patron Saint’ of Comprehensive Education: an interview with Clyde Chitty. Part One MELISSA BENN & JANE MARTIN ABSTRACT FORUM invited Melissa Benn and Jane Martin to interview Clyde Chitty, a brilliant and effective classroom and university teacher, one of the most well-known advocates of comprehensive education, a long-standing member of FORUM’s editorial board, and for two decades co-editor of the publication. It was Michael Armstrong who called him ‘the patron saint of the movement for comprehensive education’, in a card written to Clyde when he stepped away from regular duties with the FORUM board. In three 45-minute interviews, conducted at Clyde’s home, Clyde shared reflections with us on a working life as a teacher-researcher who notably campaigned for the universal provision of comprehensive state education. In this article, which comprises Part One of the interviews (Part Two will appear in the spring 2018 number of FORUM), Clyde’s unshakeable conviction that education has the power to enhance the lives of all is illustrated by plentiful examples from his work-life history. Clyde Chitty grew up in London just after the Second World War during the glory days of radio, for which he remains nostalgic. As a child, he loved all the popular series on Children’s Hour and other familiar programmes such as ‘Dick Barton – Special Agent’, and he is still a huge fan of ‘The Archers’. Clyde passed his 11-plus and was educated at a single-sex direct grant grammar school in Hammersmith between 1955 and 1962. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton Richardson, Martin Howard How to cite: Richardson, Martin Howard (1998) The development of secondary education in county Durham, 1944-1974, with special reference to Ferryhill and Chilton, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN COUNTY DURHAM, 1944-1974, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FERRYHILL AND CHILTON MARTIN HOWARD RICHARDSON This thesis grew out of a single question: why should a staunch Labour Party stronghold like County Durham open a grammar school in 1964 when the national Party was so firmly committed to comprehensivization? The answer was less easy to find than the question was to pose. -

Ivybridge Community College Jubilee 1958 – 2019 EDUCATIONAL

Ivybridge Community College Jubilee 1958 – 2019 EDUCATIONAL CHANGE 1958 Headteacher: Mr K A Baker White Paper Secondary Education for All: A New Drive (December) 1958 announced a £300m school building programme consisting mostly of new secondary modern schools 1959 Education Act (July) 1959 Minister of Education ‘to make contributions, grants and loans in respect of aided schools and special agreement schools’ Secondary School Examinations other than the GCE (July) Report of the Committee appointed by the Secondary School 1960 Examinations Council which led to the introduction of Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) in 1965 Education Act (March) Placed legal obligation on parents to ensure that children received a 1962 suitable education at school or otherwise. Local Education Authorities legally responsible for ensuring that pupils attend school 1963 Robin Pedley The Comprehensive School – reprinted many times Ministry of Education reorganised as the Department of Education and 1964 Science 1964 Education Act (July) 1964 Allowed the creation of middle schools 1965 Bachelor of Education (Bed) courses begin Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) introduced in England and 1965 Wales 1967 The Plowden Report - Children and their Primary Schools (January) Margaret Thatcher appointed Shadow Secretary of State for Education 1967 (January) 1968 Education Act (July) 1968 laid down rules about changing the character of a school (for example to a comprehensive) School Meals Agreement 1968 Teachers were no longer obliged to supervise children -

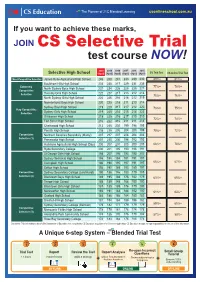

2020 Selective Trial Test Result

The Pioneer of 21C Blended Learning csonlineschool.com.au If you want to achieve these marks, JOIN CS Selective Trial test course NOW! 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Selective High School (April) (April) (April) (April) (April) (April) CS Trial Test CS online Trial Test Most Competitive Selective James Ruse Agricultural High School 246 250 241 243 239 230 80%+ 81%+ Baulkham Hills High School 234 230 217 229 231 235 Extremely 77%+ 78%+ North Sydney Boys High School 231 234 226 225 225 221 Competitive Hornsby Girls High School 222 227 217 213 212 216 Selective 75%+ 76%+ North Sydney Girls High School 222 226 216 216 212 219 Normanhurst Boys High School 220 225 218 211 210 214 Sydney Boys High School 219 229 217 217 212 220 Very Competitive 73%+ 75%+ Sydney Girls High School 219 225 216 215 214 223 Selective Girraween High School 218 225 216 217 210 210 72%+ 74%+ Fort Street High School 216 222 215 211 211 216 Chatswood High School 213 215 202 199 198 198 Penrith High School 208 215 205 204 200 199 70%+ 72%+ Competitive Northern Beaches Secondary (Manly) 207 217 207 206 204 206 Selective (1) Parramatta High School 201 210 200 194 192 193 Hurlstone Agricultural High School (Day) 200 207 201 203 200 205 68%+ 70%+ Ryde Secondary College 200 201 195 190 186 191 St George Girls High School 198 207 195 195 195 202 Sydney Technical High School 198 198 194 191 191 197 Caringbah High School 196 198 195 197 191 197 65%+ 67%+ Sefton High School 192 197 189 193 189 197 Competitive Sydney Secondary College (Leichhardt) 190 186 186 183 179 185 Selective -

The Life and Times of the Remarkable Alf Pollard

1 FROM FARMBOY TO SUPERSTAR: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REMARKABLE ALF POLLARD John S. Croucher B.A. (Hons) (Macq) MSc PhD (Minn) PhD (Macq) PhD (Hon) (DWU) FRSA FAustMS A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology, Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August 2014 2 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 12 August 2014 3 INTRODUCTION Alf Pollard’s contribution to the business history of Australia is as yet unwritten—both as a biography of the man himself, but also his singular, albeit often quiet, achievements. He helped to shape the business world in which he operated and, in parallel, made outstanding contributions to Australian society. Cultural deprivation theory tells us that people who are working class have themselves to blame for the failure of their children in education1 and Alf was certainly from a low socio-economic, indeed extremely poor, family. He fitted such a child to the letter, although he later turned out to be an outstanding counter-example despite having no ‘built-in’ advantage as he not been socialised in a dominant wealthy culture. -

Download (514Kb)

Inclusion, Cultural Diversity and Schooling I The first thing I should say, before I say anything about inclusion, the curriculum and the pupil experience, because this is more than just about the classroom, is thank you for everything you will go on to do in stimulating teaching and learning in schools and elsewhere. That ‘thank you’ for what you will do in the future is partly in the knowledge that you, as a body of people will go on to do great things – as it is clear that people in this room have the ability to make a difference to many, many thousands of people’s lives. And, it is also partly a reminder that you should think yourself as duty-bound to do so. What is today about? Inclusion. Where should I begin? We are not born equal; neither do we live in equal circumstances, and both of these heavily influence our potential in relation to our educational outcomes and even our lifespan. These are the unsurprising headlines from two very recent surveys. One survey suggests that the social class into which we are born influences our potential lifespan – both boys and girls born today into classes A and B can expect to live into their eighties, almost ten percent longer than those born into social class C. The presence, absence or role of parents can also be very influential; and research published only last November about pupils living in care tells us that their GCSE results - an easy, if not necessarily the only significant measure of success – are as poor as they can get for an identifiable group in society. -

Quality of Education in Australia: Report of the Review Committee, April 1985

Quality of education in Australia: report of the Review Committee, April 1985. Quality of Education Review Committee ; Karmel Peter. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1985. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia reproduced by permission Report of the Review Committee '1\ 1 Quality ofeducation in Australia Report of the Review Committee APRIL 1985 UIraIy NatiOnal CIIItIe far Voc:ItioneI EduI:atioII ResearcII a..v.t 11. 31IC1ngWiIiIM St. Adelaide SA 5000 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1985 © Commonwealth of Australia 1985 ISBN 0 644 04131 5 y\tIldU -I 11::n1l'NIt!Jj!f ~316noitsac1V 10t ~ 1","",151,j i .18 I'I'IIllffiW QIIi)II " .tt CsveJ j 0Il01! lie ~!~!:IA _,1 Printed by Canberra Publishing and Printing Co., Fyshwick. A.C.T. Quality of Education Review Committee MLC Tower, Woden PO Box 34, Woden Australian Capital Territory 2606 Tel. (062) 89·7481; 89·7057 30 April 1985 Senator the Hon. Susan Ryan, Minister for Education, Parliament House, CANBERRA, ACT 2600 Dear Minister, On 14 August 1984 you announced the appointment of the Quality of Education Review Committee to examine the effectiveness of present Commonwealth involvement in primary and secondary education with a view to assisting the Government to develop clear, more efficient strategies for directing its funds for school level education. We have now completed our task and are pleased to submit to you the unanimous report of the Committee. In the preparation of this document the Committee was greatly assisted by education and labour market authorities as well as by national interest groups. We express our appreciation for their cooperation. -

Participating Schools List

PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS LIST current at Saturday 11 June 2016 School / Ensemble Suburb Post Code Albion Park High School Albion Park 2527 Albury High School* Albury 2640 Albury North Public School* Albury 2640 Albury Public School* Albury 2640 Alexandria Park Community School* Alexandria 2015 Annandale North Public School* Annandale 2038 Annandale Public School* Annandale 2038 Armidale City Public School Armidale 2350 Armidale High School* Armidale 2350 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Killarney Beacon Hill 2100 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Pennant Hills Pennant Hills 2120 Ashbury Public School Ashbury 2193 Ashfield Boys High School Ashfield 2131 Asquith Girls High School Asquith 2077 Avalon Public School Avalon Beach 2107 Balgowlah Heights Public School* Balgowlah 2093 Balgowlah North Public School Balgowlah North 2093 Balranald Central School Balranald 2715 Bangor Public School Bangor 2234 Banksmeadow Public School* Botany 2019 Bathurst Public School Bathurst 2795 Baulkham Hills North Public School Baulkham Hills 2153 Beacon Hill Public School* Beacon Hill 2100 Beckom Public School Beckom 2665 Bellevue Hill Public School Bellevue Hill 2023 Bemboka Public School Bemboka 2550 Ben Venue Public School Armidale 2350 Berinba Public School Yass 2582 Bexley North Public School* Bexley 2207 Bilgola Plateau Public School Bilgola Plateau 2107 Billabong High School* Culcairn 2660 Birchgrove Public School Balmain 2041 Blairmount Public School Blairmount 2559 Blakehurst High School Blakehurst 2221 Blaxland High School Blaxland 2774 Bletchington -

AMS112 1973-1974 Lowres Web

' I CO.VER: Preparators put the ftnal touches to th.e. ie/1 model in the Australian Museum's Hall of Life. I REPORT OF THE rfRUSTEES OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE, 1974 Ordered to be printed, 20 March, 1975 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Trustees, Director and staff of the Australian Museum have pleasure in thanki ng t he fo llowi ng organizations which provided funds by way of research grants or grants-in-aid, assisting Museum staff in undertaking research and other projects of interest to the Museum: Australian Research Grants Committee Australian Biological Resources Study Interim Council Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Australian Council for the Arts CSIRO Science and Industry Endowment Fund The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs lan Potter Foundation The Commonwealth Foundation The British Council The Myer Foundation BHP Ltd james Kirby Foundation Bernard Van Leer Foundation Argyle Arts Centre Further acknowledgements are listed under Appendix 2. COVER: Preparators put the finishing touches to the cell model in The Australian Museum's Hall of Life. (Photo: Howard Hughes Aurtraflan Museum.) 2 THE AU STRA LIAN MUSEUM BOARD OF TRUSTEES PRESIDENT K. l. Sutherland, D.Sc., Ph.D., F.A.A., A.R.I.C., M.I.M.M.Aust., F.R.A.C.I. CROWN TRUSTEE W. H. Maze, M.Sc. OFFICIAL TRUSTEES ELECTIVE TRUSTEES The Hon. the Chief justice Sir Frank McDowell The Hon. the President of the Legislative Council R. J. Noble, C.B.E., B.Sc. Agr., M.Sc., Ph.D. The Hon. the Chief Secretary G. A. johnson, M.B.E.