Existentialism in Graham Greene's "The Name of Action", "The Heart of the Matter", "A Burnt-Out Case": the Theme of Betrayal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

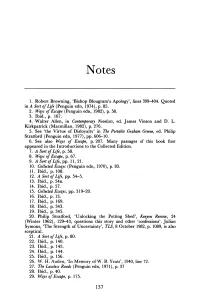

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

Nesetrilovai Reflection1930s O

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Reflection of the 1930´s British Society in Graham Greene´s Brighton Rock Iva Nešetřilová Bachelor thesis 2017 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně. V Pardubicích dne 17.3.2017 Iva Nešetřilová Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Olga Roebuck, M.Litt. Ph.D. for giving me the opportunity to choose this topic, for her professional help, advice, and, especially, for the time she had spent when consulting my work. Annotation This paper examines and analyses the reflection of British Society in the novel Brighton Rock by Graham Green. The first part explores the situation in Britain around the 1930s, the period when the book was written and published, and briefly focuses on the changing landscape brought about by the Depression and aftermath of the First World War. The emphasis is confined mostly to how these changes affected the lower classes, and a brief description of what constitutes working class is provided. -

Moral Values in Espionage Novels by Graham Greene

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Viktoria Fedorova Moral Values In Espionage Novels by Graham Greene Bachelor's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2017 / declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. Viktória Fedorová 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, PhD. for all his valuable advice. I would also like to thank my family, my partner and my friends for their support. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Graham Greene: Life and Vision 10 2.1. Espionage 15 2.2. Greene and Catholicism 17 2.3. The Entertainments and "Serious Novels" 21 3. The Ministry of Fear 23 4. The Quiet American 32 5. The Comedians 46 6. Conclusion °1 7. Works Cited 65 8. Resume (English) 67 9. Resume (Czech) 68 4 1. Introduction The aim of this thesis is to analyse and compare the treatment of moral values in three espionage novels by Graham Greene- The Ministry of Fear, The Quiet American and The Comedians- to show that the debate of moral values in Greene's novels is closely connected with the notion that the gravity of sins committed is connected to the amount of pain one's decision causes to other human beings. The evil committed by his characters is to be judged individually and one of his characters' greatest fears is the fear to cause the pain to other human beings. Espionage novels were used because Greene's experience with espionage is often projected into his novels and it is often central to the plot. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

The Destructors Graham Greene

The Destructors Graham Greene Online Information For the online version of BookRags' The Destructors Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-destructors/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Wireless Women: the “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University

47 Wireless Women: The “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University All popular fi ction must feature a romantic couple, and so it is in the open- ing pages of Brighton Rock (1938) that Graham Greene introduces Pinkie and Rose, the teenagers whose abrasive courtship and perverse marriage will both enact and travesty this convention as the novel unfolds. When Pinkie fi rst meets Rose, she is working at Snow’s as a waitress. Entering the establishment, Pinkie encounters a wireless set “droning a programme of weary music broadcast by a cinema organist—a great vox humana trembl[ing] across the crumby stained desert of used cloths: the world’s wet mouth lamenting over life” (24). This reference to the weary lamentations of wireless remains an isolated detail until moments before Pinkie takes his fatal plunge over the cliff in the novel’s closing pages. Having taken Rose up the coast from Brighton with plans to facilitate her suicide, the couple sits for a few awkward moments in an empty hotel lounge. As Rose works on her half of the couple’s double-suicide note, to be left behind for the benefi t of “Daily Express readers, to what one called the world” (260), wireless makes a brief but meaningful re-appearance as that world speaks back. “The wireless was hidden behind a potted plant; a violin came wailing out, the notes shaken by atmospherics,” writes Greene (250). Later, the violin fades away and “a time signal pinged through the rain. A voice behind the plant gave them the weather report—storms coming up from the Continent, a depression in the Atlantic, tomorrow’s forecast” (251). -

THE HEART of the MATTER by Graham Greene

THE HEART OF THE MATTER by Graham Greene THE AUTHOR Graham Greene (1904-1991) was born in Berkhamsted, England. He had a very troubled childhood, was bullied in school, on several occasions attempted suicide by playing Russian roulette, and eventually was referred for psychiatric help. Writing became an important outlet for his painful inner life. He took a degree in History at Oxford, then began work as a journalist. His conversion to Catholicism at the age of 22 was due largely to the influence of his wife-to-be, though he later became a devout follower of his chosen faith. His writing career included novels, short stories, and plays. Some of his novels dealt openly with Catholic themes, including The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948), and The End of the Affair (1951), though the Vatican strongly disapproved of his portrayal of the dark side of man and the corruption in the Church and in the world. Others were based on his travel experiences, often to troubled parts of the world, including Mexico during a time of religious persecution, which produced The Lawless Roads (1939) as well as The Power and the Glory, The Quiet American (1955) about Vietnam, Our Man in Havana (1958) about Cuba, The Comedians (1966) about Haiti, The Honorary Consul (1973) about Paraguay, and The Human Factor (1978) about South Africa. Many of his novels were later made into films. Greene was also considered one of the finest film critics of his day, though one particularly sharp review attracted a libel suit from the studio producing Shirley Temple films when he suggested that the sexualization of children was likely to appeal to pedophiles. -

An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War Leann Do the College of Wooster

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2012 Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War Leann Do The College of Wooster Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Do, Leann, "Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War" (2012). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 3826. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/3826 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2012 Leann Do The College of Wooster Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War by Leann A. Do Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Senior Independent Study Supervised by Dr. Madonna Hettinger Department of History Spring 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii List of Figures iv Timeline v Maps vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 The Two Vietnams Chapter Two: Historiography of the Vietnam War 5 in American Scholarship Chapter Three: Theory and Methodology 15 of Oral History Chapter Four: “I’m an Ordinary Person” 30 A Husband and -

Framing 'The Other'. a Critical Review of Vietnam War Movies and Their Representation of Asians and Vietnamese.*

Framing ‘the Other’. A critical review of Vietnam war movies and their representation of Asians and Vietnamese.* John Kleinen W e W ere Soldiers (2002), depicting the first major clash between regular North-Vietnamese troops and U.S. troops at Ia Drang in Southern Vietnam over three days in November 1965, is the Vietnam War version of Saving Private Ryan and The Thin Red Line. Director, writer and producer, Randall Wallace, shows the viewer both American family values and dying soldiers. The movie is based on the book W e were soldiers once ... and young by the U.S. commander in the battle, retired Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore (a John Wayne- like performance by Mel Gibson).1 In the film, the U.S. troops have little idea of what they face, are overrun and suffer heavy casualties. The American GIs are seen fighting for their comrades, not their fatherland. This narrow patriotism is accompanied by a new theme: the respect for the victims ‘on the other side’. For the first time in the Hollywood tradition, we see fading shots of dying ‘VC’ and of their widows reading loved ones’ diaries. This is not because the filmmaker was emphasizing ‘love’ or ‘peace’ instead of ‘war’, but more importantly, Wallace seems to say, that war is noble. Ironically, the popular Vietnamese actor, Don Duong, who plays the communist commander Nguyen Huu An who led the Vietnamese People’s Army to victory, has been criticized at home for tarnishing the image of Vietnamese soldiers. Don Duong has appeared in several foreign films and numerous Vietnamese-made movies about the War.