The Federalist Society Special Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let Me Just Add That While the Piece in Newsweek Is Extremely Annoying

From: Michael Oppenheimer To: Eric Steig; Stephen H Schneider Cc: Gabi Hegerl; Mark B Boslough; [email protected]; Thomas Crowley; Dr. Krishna AchutaRao; Myles Allen; Natalia Andronova; Tim C Atkinson; Rick Anthes; Caspar Ammann; David C. Bader; Tim Barnett; Eric Barron; Graham" "Bench; Pat Berge; George Boer; Celine J. W. Bonfils; James A." "Bono; James Boyle; Ray Bradley; Robin Bravender; Keith Briffa; Wolfgang Brueggemann; Lisa Butler; Ken Caldeira; Peter Caldwell; Dan Cayan; Peter U. Clark; Amy Clement; Nancy Cole; William Collins; Tina Conrad; Curtis Covey; birte dar; Davies Trevor Prof; Jay Davis; Tomas Diaz De La Rubia; Andrew Dessler; Michael" "Dettinger; Phil Duffy; Paul J." "Ehlenbach; Kerry Emanuel; James Estes; Veronika" "Eyring; David Fahey; Chris Field; Peter Foukal; Melissa Free; Julio Friedmann; Bill Fulkerson; Inez Fung; Jeff Garberson; PETER GENT; Nathan Gillett; peter gleckler; Bill Goldstein; Hal Graboske; Tom Guilderson; Leopold Haimberger; Alex Hall; James Hansen; harvey; Klaus Hasselmann; Susan Joy Hassol; Isaac Held; Bob Hirschfeld; Jeremy Hobbs; Dr. Elisabeth A. Holland; Greg Holland; Brian Hoskins; mhughes; James Hurrell; Ken Jackson; c jakob; Gardar Johannesson; Philip D. Jones; Helen Kang; Thomas R Karl; David Karoly; Jeffrey Kiehl; Steve Klein; Knutti Reto; John Lanzante; [email protected]; Ron Lehman; John lewis; Steven A. "Lloyd (GSFC-610.2)[R S INFORMATION SYSTEMS INC]"; Jane Long; Janice Lough; mann; [email protected]; Linda Mearns; carl mears; Jerry Meehl; Jerry Melillo; George Miller; Norman Miller; Art Mirin; John FB" "Mitchell; Phil Mote; Neville Nicholls; Gerald R. North; Astrid E.J. Ogilvie; Stephanie Ohshita; Tim Osborn; Stu" "Ostro; j palutikof; Joyce Penner; Thomas C Peterson; Tom Phillips; David Pierce; [email protected]; V. -

Billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife Dies at 82

BUSINESS SATURDAY, JULY 5, 2014 European regulator tells banks to shun Bitcoin LONDON: Europe’s top banking regulator would require a substantial body of regula- But regulators argue the lack of legal AMF. Bitcoin prices surged to $1,240 in yesterday called on the region’s banks not to tion, some components of which would need framework governing the currency, the November last year before they crashed fol- deal in virtual currencies such as Bitcoin until to be developed in more detail,” it added. opaque way it is traded and its volatility make lowing moves by exchanges, financial institu- rules are developed to stop them being Virtual currencies, most famously Bitcoin, it dangerous. Mt Gox, once the world’s tions and the government to rein in the virtual abused. The European Banking Authority have come under increasing scrutiny by biggest Bitcoin exchange, filed for bankruptcy currency. (EBA) said it had identified more than 70 risks financial regulators as their popularity has in Japan this year and at least 11 banks in its They currently trade at more than $600 a related to trading in virtual currencies, includ- grown. Launched in 2009 by a mysterious key market of China have stopped handling Bitcoin. The EBA said that the risks of virtual ing their vulnerability to crime and money computer guru, Bitcoin is a form of cryptogra- the currency. Bitcoin’s reputation was also currencies “outweigh the benefits,” such as laundering. phy-based e-money that offers a largely damaged when US authorities seized tens of faster and cheaper transactions, “which in the The London-based body in a statement anonymous payment system and can be thousands as part of an investigation into dark European Union remain less pronounced”. -

Who Is Richard Mellon Scaife?

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 24, Number 15, April 4, 1997 Who is Richard Mellon Scaife? Part 2 of our expose on the moneybags behind the media campaign against the President. Edward Spannaus reports on Scaife and the Bush "secret government. .. Richard Mellon Scaifehas recently come into prominence as Mont Pelerin Society. Under the guise of "Thatcherism," the bankroller of a news-media campaign aimed at President these groups provided the social and economic policies, and Clinton, while he is sponsoring a cushy "retirement" position much of the staffing, for the so-called "Reagan Revolution," for Whitewater special prosecutor Kenneth Starr. In Part 1 and more recently, for the Gingrich-Gramm gang in the wake (EIR, March 21), we showed that "Dickie" Scaife has been of the Republican Party takeover of Congress in the 1994 deployed for almost 25 years by the old Office of Strategic elections. One could say that the earnest money for the "Con Services Anglo-Americanfinancier-intelligencecircles, to do tract with America" was paid by Dickie Scaife. exactly this sort of thing. A third distinctive cluster of organizations funded by Scaife are the right-wing legal foundations and litigation Since Dickie Scaife was allowed to take over the Scaife family groups; originally founded to counter civil libertarians and foundations and trusts in 1973, he has been a principal funder environmentalists, they have increasingly become pro-envi of that network of nominally "conservative" foreign policy ronmentalist and libertarian in their outlook-as well as fi think-tanks which operates as a training ground and as the nancing legal attacks on President Clinton and the Clinton agenda-setter for the foreign service and intelligence commu administration. -

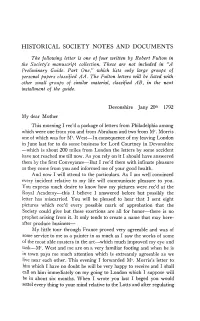

Other Small Groups of Similar Material, Classified AB, in the Next Installment of the Guide

HISTORICAL SOCIETY NOTES AND DOCUMENTS The following letter is one oj jour written by Robert Fulton in the Society's manuscript collection. These are not included in "A Preliminary Guide. Part One" which lists only large groups of personal papers classified AA. The Fulton letters willbe listed with other small groups of similar material, classified AB, in the next installment of the guide. Devonshire Jany 20th 1792 My dear Mother This morning Irec'd a package of letters from Philadelphia among which were one from you and from— Abraham and two from Mr.Morris one of which was for Mr.West Inconsequence of my leaving London —inJune last for to do some business for Lord Courtney inDevonshire which is about 200 miles from London the letters by some accident have not reached me tillnow.—As you rely on itIshould have answered them by the firstConveyance But Irec'd them with infinate pleasure as they come from you and informed me of your good health. And now Iwillattend to the particulars. As Iam well convinced every incident relative to my life will communicate pleasure to you. You express much— desire to know how my pictures were rec'd at the Royal Academy this Ibelieve Ianswered before but possibly the letter has miscarried. You willbe pleased to hear that Isent eight pictures which rec'd every possible mark of approbation— that the Society could give but these exertions are all for honor there is no prophet arising from it.Itonly tends to create a name that may here- after produce business — My little tour through France proved very agreeable and was of some service to me as a painter in—as much as Isaw the works of some of the—most able masters in the art which much improved my eye and task Mr. -

What the Federalist Society Stands for Group Is Haven for Conservative Thought by Michael A

What the Federalist Society Stands For Group Is Haven for Conservative Thought By Michael A. Fletcher Washington Post Staff Writer Friday, July 29, 2005; Page A21 After President Bush tapped John G. Roberts Jr. for the Supreme Court, the nominee was widely reported to be a member of the Federalist Society -- an assertion that White House officials vigorously disputed. When it was later disclosed that Roberts was once listed as serving on the steering committee of the group's Washington chapter, Bush aides continued to insist that Roberts has no recollection of ever being a full-fledged member of the conservative legal group. The eagerness of the White House to distance Roberts from the Federalist Society baffled many conservatives. They believe the reaction fed a false perception that membership in the organization -- an important pillar of the conservative legal movement -- was something nefarious that would damage Roberts's chances of confirmation. "Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Federalist Society?" asked Roger Pilon, a vice president at the libertarian Cato Institute, mocking the suspicion that swirls around the group. "The Republicans and the White House in particular should take this issue on head-on. What are we talking about here? The Communist Party? The Ku Klux Klan? This is an organization of conservative and libertarian law students, lawyers and legal scholars." Launched 23 years ago by a group of conservative students who felt embattled by liberals on the campuses of some of the nation's most elite law schools, the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies has grown into one of the nation's most influential legal organizations. -

Clinton, Conspiracism, and the Continuing Culture

TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL PublicEye RESEARCH ASSOCIATES SPRING 1999 • Volume XIII, No. 1 Clinton, Conspiracism, and the Continuing Culture War What is Past is Prologue by Chip Berlet cal of the direct-mail genre, it asked: culture war as part of the age-old battle he roar was visceral. A torrent of Which Clinton Administration against forces aligned with Satan. sound fed by a vast subconscious scandal listed below do you consider to Demonization is central to the process. Treservoir of anger and resentment. be “very serious”? Essayist Ralph Melcher notes that the “ven- Repeatedly, as speaker after speaker strode to The scandals listed were: omous hatred” directed toward the entire the podium and denounced President Clin- Chinagate, Monicagate, Travel- culture exemplified by the President and his ton, the thousands in the cavernous audito- gate, Whitewater, FBI “Filegate,” wife succeeded in making them into “polit- rium surged to their feet with shouts and Cattlegate, Troopergate, Casinogate, ical monsters,” but also represented the applause. The scene was the Christian Coali- [and] Health Caregate… deeper continuity of the right's historic tion’s annual Road to Victory conference held In addition to attention to scandals, distaste for liberalism. As historian Robert in September 1998—three months before the those attending the annual conference clearly Dallek of Boston University puts it, “The House of Representatives voted to send arti- opposed Clinton’s agenda on abortion, gay Republicans are incensed because they cles of impeachment to the Senate. rights, foreign policy, and other issues. essentially see Clinton…as the embodi- Former Reagan appointee Alan Keyes Several months later, much of the coun- ment of the counterculture’s thumbing of observed that the country’s moral decline had try’s attention was focused on the House of its nose at accepted wisdoms and institu- spanned two decades and couldn’t be blamed Representatives “Managers” and their pursuit tions of the country.” exclusively on Clinton, but when he of a “removal” of Clinton in the Senate. -

How Right-Wing Billionaires Infiltrated Higher Education

• • • 28 THE CHRONICLE REVIEW How Right-Wing Billionaires Infiltrated Higher Education Chronicle Review illustration by Scott Seymour, original image by Randy Lyhus By Jane Mayer FEBRUARY 12, 2016 PREMIUM If there was a single event that galvanized conservative donors to try to wrest control of higher education in America, it might have been the uprising at Cornell University on April 20, 1969. That afternoon, during parents’ weekend at the Ithaca, N.Y., campus, some 80 black students marched in formation out of the student union, which they had seized, with their clenched fists held high in black-power salutes. To the shock of the genteel Ivy League community, several were brandishing guns. At the head of the formation was a student who called himself the "Minister of Defense" for Cornell’s Afro-American Society. Strapped across his chest, Pancho Villa-style, was a sash-like bandolier studded with bullet cartridges. Gripped nonchalantly in his right hand, with its butt resting on his hip, was a glistening rifle. Chin held high and sporting an Afro, goatee, and eyeglasses reminiscent of Malcolm X, he was the face of a drama so infamous it was regarded for years by conservatives such as David Horowitz as "the most disgraceful occurrence in the history of American higher education." John M. Olin, a multimillionaire industrialist, wasn’t there at Cornell, which was his alma mater, that weekend. He was traveling abroad. But as a former Cornell trustee, he could not have gone long without seeing the iconic photograph of the armed protesters. What came to be known as "the Picture" quickly ricocheted around the world, eventually going on to win that year’s Pulitzer Prize. -

Richard Mellon Scaife

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 25, Number 14, April 3, 1998 asterisk). In some cases the same individuals played active, What is somewhat less widely known, is the role that albeit different, roles in the two actions. Richard Mellon Scaife played in the 1980s “Get LaRouche” Following the four charts, which represent overlays of operation, the combined legal and media assault against the data organized by forms of action, we have included an anno- noted American System political economist, and intellectual tated index of names, to help the reader through the maze author of President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative. of detail. Mellon Scaife directly bankrolled the media salon that churned out a constant stream of Goebbels-like anti- The analysis LaRouche hate propaganda, through such media outlets as It must be emphasized that the data presented in this spe- NBC-TV, Readers Digest, the Washington Post, Business cial report are by no means complete. However, the data pro- Week, the New Republic, and the Wall Street Journal. The vide a road-map of the apparatus under investigation, and Get LaRouche salon was an integral part of the “Public Diplo- will, hopefully, provoke further inquiry into two aspects, in macy” unit, run out of the White House, by George Bush and particular, of the ongoing investigation: his gopher Oliver North, which was later exposed as part First, the institutions and individuals who have been iden- of the “secret parallel government” behind the Iran-Contra tified in both the Get LaRouche and Get Clinton operations fiasco. Both the Iran-Contra guns-for-drugs criminal enter- warrant special investigative followup. -

Bullet Hole’ Campaign?

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 25, Number 4, January 23, 1998 EIRNational Who’s behind the Ron Brown ‘bullet hole’ campaign? by Edward Spannaus Among right-wing Clinton-haters, on the talk shows and on tions, mapping out the post-war reconstruction of Bosnia and the Internet, one of the hottest “underground” topics is the Croatia; strategically, this was a direct challenge to the long- story that the late Commerce Secretary Ron Brown may have standing Anglo-French policy of keeping the Balkans en- died from a bullet in the head, rather than from the plane crash meshed in bloody religious and ethnic turmoil. which occurred in Croatia in April 1996. Within days and weeks, many theories were floating A number of black activists and political leaders have also around that Brown was the victim of an assassination plot. been drawn into the controversy, and are now asking for an One of the most elaborated scenarios was that circulated by investigation of the spurious “bullet hole” story. Nick Guarino, a convicted fraudster, and fugitive, who pub- How did this story get started? What has given rise to this lishes the mysterious Wall Street Underground newsletter bizarre, de facto coalition between groups which were on which regularly accuses Clinton of carrying out treason with opposite sides during the “CIA crack-cocaine” controversy? China, while promoting Guarino’s trademark pamphlet, How is it that many of the same people who were accusing “How to Survive and Profit from the Clinton Crash.” Guari- Ron Brown of criminality, and even treason, in life, are now no’s imaginative scenario had White House agents using a suddenly his biggest defenders in death? And why is a wealthy false beacon signal to send Brown’s plane crashing into a scion of the Mellon banking family, Richard Mellon Scaife, mountain and then burning, for the reason that Brown was who was trained 25 years ago by British Intelligence and the about to go to jail, and had threatened to take Clinton down CIA in news-media manipulation, spearheading the “bullet with him. -

Who Is Richard Mellon Scaife?

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 24, Number 16, April 11, 1997 Who is Richard Mellon Scaife? Part3 of our expose on the moneybags behind the media assault against President Clinton and Lyndon LaRouche. Edward Spannaus reports. A certain irony exists, in the fact of Richard Mellon Scaife's treated as a full-fledged Mellon. Dickie would later describe bankrolling of a network of anti-capitalist Mont Pelerin Soci his father as "sucking hind tit" to the Mellons. ety think-tanks in the U.S. The Mont Pelerin Society-the As he grew older, young Dickie became resentful of the modem-day embodiment of the feudal, aristocratic "Austrian treatment that his father had gotten at the hands of the Mel School" of monetarist economics-bitterly hates industrial Ions, and he often made his animosity known, particularly capitalism and any form of centralized, dirigist measures toward his uncle, Richard King Mellon. Dickie became through which a nation-state can build up its own industrial known as a "bull in a china shop." Some attributed his impetu technological base, while restricting access to predatory inter ousness to his being thrown by a horse at age 9; his skull was national financial looters. partially crushed, and was repaired with an aluminum plate The fact of the matter is that the Pittsburgh Scaife family and much plastic surgery. was a pioneering U.S. industrial family, especially in the 19th As soon as his father died in 1952, Dickie sold off the century. At one time, the family was wont to boast that the Scaife Company for one dollar. -

Lessons from 1964

04-179 (35) Ch 35 6/17/04 6:51 AM Page 403 • 35 • Lessons from 1964 Eric Alterman Building on my book What Liberal Media? this chapter focuses on the rise of con- servative media over the last forty years. It concludes with lessons for advocacy and media in support of the foreign, economic, and domestic policy alternatives set forth in this book. Primarily, I want to consider the “elite” media, located largely in New York and Washington. The elite media are composed mostly of the top political re- porters for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, the top networks, the top opinion magazines, and the cable news shows. When we discuss the media today, there are many issues on the table. They in- clude the phony charge of “liberal bias,” the terrible problem of media ownership concentration, the focus on profits that is killing so many media companies, and the collapse of journalistic standards. But even if these issues didn’t exist, and even if there were a perfect candidate who ran on the kinds of positions staked out in this book, that candidate still would have difficulty communicating the value of those positions to the American public. Why? To answer that question, it is necessary to go back to the 1964 election. That election was key to how the media have changed in our lifetimes. In 1964, the media were conservative in many ways. But the elite media were more liberal than the rest of the nation on most issues. -

Lapham, L. Tentacles of Rage

Tentacles of Rage: The Republican propaganda mill, a brief history LE... http://www.mindfully.org/Reform/2004/Republican-Propaganda1sep04.htm Tentacles of Rage The Republican propaganda mill, a brief history LEWIS H LAPHAM / Harpers Magazine v.309, n.1852, September 2004 1sep04 When, in all our history, has anyone with ideas so bizarre, so archaic, so self-confounding, so remote from the basic American consensus, ever got so far? —Richard Hofstadter In company with nearly every other historian and political journalist east of the Mississippi River in the summer of 1964, the late Richard Hofstadter saw the Republican Party's naming of Senator Barry Goldwater as its candidate in that year's presidential election as an event comparable to the arrival of the Mongol hordes at the gates of thirteenth-century Vienna. The "basic American consensus" at the time was firmly liberal in character and feeling, assured of a clear majority in both chambers of Congress as well as a sympathetic audience in the print and broadcast press. Even the National Association of Manufacturers was still aligned with the generous impulse of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, accepting of the proposition, as were the churches and the universities, that government must do for people what people cannot do for themselves.* * With regard to the designation "liberal," the economist John K. Galbraith said in 1964, "Almost everyone now so describes himself." Lionel Trilling, the literary critic, observed in 1950 that "In the United States at this time, liberalism is not only the