Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume I: China, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Contents Introduction I STRATEGIC VISIONS for EAST ASIA Toward

Contents Introduction I STRATEGIC VISIONS FOR EAST ASIA Toward Greater U.S.-Japan-India Strategic Dialogue and Coordination Mike Green Arc of Freedom and Prosperity Heigo Sato India’s Strategic Vision Suba Chandran II THE RISE OF CHINA Dealing with a Rising Power: India-China Relations and the Reconstruction of Strategic Partnerships Alka Acharya The Prospect of China Up to 2020: A View from Japan Yasuhiro Matsuda The United States and a Rising China Derek Mitchell III NONPROLIFERATION Strengthening the Nonproliferation Regime in the Era of Nuclear Renaissance: A Common Agenda for Japan, the United States, and India Nobumasa Akiyama Global Nonproliferation Dynamics: An Indian Perspective Lawrence Prabhakar Nonproliferation Players and their Policies Jon Wolfstal IV ENERGY SECURITY Trends in Energy Security Mikkal Herberg 1 Japan ’s Energy Security Policy Manabu Miyagawa India’s Energy Security Chietigj Bajpaee V ECONOMIC CONVERGENCE A U.S. Perspective of Economic Convergence in East Asia Krishen Mehta New Open Regionalism? Current Trends and Perspectives in the Asia-Pacific Fukunari Kimura VI SOUTHEAST ASIA U.S. Perspectives on Southeast Asia: Opportunities for a Rethink Ben Dolven Southeast Asia: A New Regional Order Nobuto Yamamoto India’s Role in Southeast Asia: The Logic and Limits of Cooperation with the United States and Japan Sadanand Dhume VII COUNTER-TERRORISM Japan’s Counterterrorism Policy Naofumi Miyasaka Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and Japan: An Indian Perspective Manjeet Singh Pardesi VIII MARITIME -

Admiral Sunil Lanba, Pvsm Avsm (Retd)

ADMIRAL SUNIL LANBA, PVSM AVSM (RETD) Admiral Sunil Lanba PVSM, AVSM (Retd) Former Chief of the Naval Staff, Indian Navy Chairman, NMF An alumnus of the National Defence Academy, Khadakwasla, the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington, the College of Defence Management, Secunderabad, and, the Royal College of Defence Studies, London, Admiral Sunil Lanba assumed command of the Indian Navy, as the 23rd Chief of the Naval Staff, on 31 May 16. He was appointed Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee on 31 December 2016. Admiral Lanba is a specialist in Navigation and Aircraft Direction and has served as the navigation and operations officer aboard several ships in both the Eastern and Western Fleets of the Indian Navy. He has nearly four decades of naval experience, which includes tenures at sea and ashore, the latter in various headquarters, operational and training establishments, as also tri-Service institutions. His sea tenures include the command of INS Kakinada, a specialised Mine Countermeasures Vessel, INS Himgiri, an indigenous Leander Class Frigate, INS Ranvijay, a Kashin Class Destroyer, and, INS Mumbai, an indigenous Delhi Class Destroyer. He has also been the Executive Officer of the aircraft carrier, INS Viraat and the Fleet Operations Officer of the Western Fleet. With multiple tenures on the training staff of India’s premier training establishments, Admiral Lanba has been deeply engaged with professional training, the shaping of India’s future leadership, and, the skilling of the officers of the Indian Armed Forces. On elevation to Flag rank, Admiral Lanba tenanted several significant assignments in the Navy. As the Chief of Staff of the Southern Naval Command, he was responsible for the transformation of the training methodology for the future Indian Navy. -

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

Rule India Andpakistansanctionsother 15 Cfrparts742and744 Bureau Ofexportadministration Commerce Department of Part II 64321 64322 Federal Register / Vol

Thursday November 19, 1998 Part II Department of Commerce Bureau of Export Administration 15 CFR Parts 742 and 744 India and Pakistan Sanctions and Other Measures; Interim Rule federal register 64321 64322 Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 223 / Thursday, November 19, 1998 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Regulatory Policy Division, Bureau of missile technology reasons have been Export Administration, Department of made subject to this sanction policy Bureau of Export Administration Commerce, P.O. Box 273, Washington, because of their significance for nuclear DC 20044. Express mail address: explosive purposes and for delivery of 15 CFR Parts 742 and 744 Sharron Cook, Regulatory Policy nuclear devices. [Docket No. 98±1019261±8261±01] Division, Bureau of Export To supplement the sanctions of Administration, Department of RIN 0694±AB73 § 742.16, this rule adds certain Indian Commerce, 14th and Pennsylvania and Pakistani government, parastatal, India and Pakistan Sanctions and Avenue, NW, Room 2705, Washington, and private entities determined to be Other Measures DC 20230. involved in nuclear or missile activities FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: to the Entity List in Supplement No. 4 AGENCY: Bureau of Export Eileen M. Albanese, Director, Office of to part 744. License requirements for Administration, Commerce. Exporter Services, Bureau of Export these entities are set forth in the newly ACTION: Interim rule. Administration, Telephone: (202) 482± added § 744.11. Exports and reexports of SUMMARY: In accordance with section 0436. -

List of Drdo Laboratories

LIST OF DRDO LABORATORIES LIST OF DRDO LABORATORIES The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) is an agency of the Republic of India, charged with the military's research and development, headquartered in New Delhi, India. It was formed in 1958 by the merger of the Technical Development Establishment and the Directorate of Technical Development and Production with the Defence Science Organisation. It is under the administrative control of the Ministry of Defence, Government of India. DRDO is India's largest and most diverse research organisation. The organisation includes around 5,000 scientists belonging to the Defence Research & Development Service (DRDS) and about 25,000 other scientific, technical and supporting personnel. LIST OF DRDO LABORATORIES & THEIR LOCATION Sl No Name of the Laboratory Establishment Location 1 Advanced Numerical Research & Analysis Group (ANURAG) Hyderabad 2 Aerial Delivery Research & Development Establishment (ADRDE) Agra 3 Vehicles Research & Development Establishment (VRDE) Ahmednagar 4 Naval Materials Research Laboratory (NMRL) Ambernath 5 Integrated Test Range (ITR) Balasore 6 Proof and Experimental Establishment (PXE) Balasore 7 Aeronautical Development Establishment (ADE) Bangalore Page 1 LIST OF DRDO LABORATORIES 8 Centre for Airborne Systems (CABS) Bangalore 9 Centre for Artificial Intelligence & Robotics (CAIR) Bangalore 10 Defence Avionics Research Establishment (DARE) Bangalore 11 Defence Bio-engineering & Electro-medical Laboratory (DEBEL) Bangalore 12 Gas Turbine Research Establishment -

(Defence Wing) Govenjnt of India New Vice Chief Of

PRESS INFOREATION BUREAU (DEFENCE WING) GOVENJNT OF INDIA NEW VICE CHIEF OF NAVY FLAG OFFICER COJ'INANDING—IN_CHIEF, sOVTHERN NAVAL CONMAND AND DEPUTY CHIEF OF NAVY ANNOUNCED New Delhi Agrahayana 07, 19109 November 28, 1987 Vice Admiral GN Hiranandani presently Flag Officer Commanding—in—Chief, Southern Naval Command (FOC—in—C, SNC) has been appointed as Vice Chief of Naval Staff. He will take over from Vice Admiral JG Nadkarni, the CNS Designate, who will assume the ofice of Chief of the Naval Staff on November Oth in the rank of Admiral. Vice Admiral L. Ramdas presently Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff has been appointed FOC—in—C, SNC. Vice Admiral RP Sawhney, presently Controller Warship Production and Acquisition at Naval Headnuarters, has been appointed as Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff. Vice Admiral GM Hiranandani -was commissioned in 1952 and received his initial training in the United Kingdom and later graduated from the Staff College, Greenwich (U.K.). In 1 971 he served as the Fleet Operations Officer, Western Fleet. His notable - commands at sea include that of the first Kashin class destroyer, INS Rajput which he commissioned in 1980. On promotion to flag rank he was appointed Chief of Staff, Western Naval Command and later Deputy Chief of Naval Staff in the rank of Vice Admiral. He is a recipient of the Param Vishst Seva Medal, Ati Vishist Seva, Medal and Nao Sena Medal. .1,2 -2-- Vice Admiral L. Ramdas was commissioned in 1953 and received his initial trai lug in the U.K.. A communication Specialist, he has held a number of importanf commands a't sea, which inolde Command of the Eastern Fleet, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant and a modern patrol vessel squadron. -

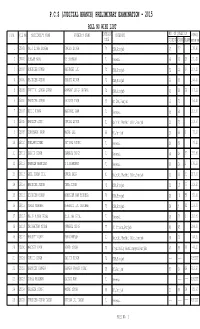

P.C.S (Judicial Branch) Preliminary Examination - 2015 Roll No Wise List S.No

P.C.S (JUDICIAL BRANCH) PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION - 2015 ROLL NO WISE LIST S.NO. ROLL NO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY CATEGORY NO. OF QUESTION MARKS CODE CORRECT WRONG BLANK (OUT OF 500) 1 25001 NAIB SINGH SANGHA GURDEV SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 48 77 130.40 2 25002 NEELAM RANI OM PARKASH 71 General 45 61 19 131.20 3 25003 AMNINDER KUMAR KASHMIRI LAL 72 ESM,Punjab 32 26 67 107.20 4 25004 RAJINDER SINGH SANGAT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 56 69 168.80 5 25005 PREETPAL SINGH GREWAL HARWANT SINGH GREWAL 72 ESM,Punjab 41 58 26 117.60 6 25006 NARENDER SINGH DAULATS INGH 86 BC ESM,Punjab 53 72 154.40 7 25007 RISHI KUMAR MANPHOOL RAM 71 General 65 60 212.00 8 25008 HARDEEP SINGH GURDAS SINGH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 52 73 149.60 9 25009 GURCHARAN KAUR MADAN LAL 85 BC,Punjab 36 88 1 73.60 10 25010 NEELAMUSONDHI SAT PAL SONDHI 71 General 29 96 39.20 11 25011 DALVIR SINGH KARNAIL SINGH 71 General 44 24 57 156.80 12 25012 KARMESH BHARDWAJ S L BHARDWAJ 71 General 99 24 2 376.80 13 25013 ANIL KUMAR GILL DURGA DASS 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 61 33 31 217.60 14 25014 MANINDER SINGH TARA SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 31 19 75 108.80 15 25015 DEVINDER KUMAR MOHINDER RAM BHUMBLA 72 ESM,Punjab 25 10 90 92.00 16 25016 VIKAS GIRDHAR KHARAITI LAL GIRDHAR 72 ESM,Punjab 34 9 82 128.80 17 25017 RAJIV KUMAR GOYAL BHIM RAJ GOYAL 71 General 45 79 1 116.80 18 25018 NACHHATTAR SINGH GURMAIL SINGH 77 SC Others,Punjab 80 45 284.00 19 25019 HARJEET KUMAR RAM PARKASH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 55 70 164.00 20 25020 MANDEEP KAUR AJMER SINGH 76 Physically Handicapped,Punjab 47 59 19 140.80 21 25021 GURDIP SINGH JAGJIT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab --- --- --- ABSENT 22 25022 HARPREET KANWAR KANWAR JAGBIR SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 83 24 18 312.80 23 25023 GOPAL KRISHAN DAULAT RAM 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT 24 25024 JAGSEER SINGH MODAN SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 33 58 34 85.60 25 25025 SURENDER SINGH TAXAK ROSHAN LAL TAXAK 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT PAGE NO. -

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, editors Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. ISBN 0-9747255-8-7 The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street NW Twelfth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... vii Introduction......................................................................................................... ix 1. The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia Michael Krepon ............................................................................................ 1 2. Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia: Structural Factors Rodney W. Jones......................................................................................... 25 3. India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture Rajesh M. Basrur ........................................................................................ 56 4. Nuclear Signaling, Missiles, and Escalation Control in South Asia Feroz Hassan Khan ................................................................................... -

Newsletter Vol 55

NEWSLETTER PAGE NO. 26-29 MAY-JUNE 2021 | VOL. 55 Indian Men's & Women's Hockey Team announcement for the Olympics #IndiaKaGame Newsletter Vol. 55 (May & June 2021) Major Team Partner Follow Us : www.hockeyindia.org @TheHockeyIndia @hockeyindia facebook.com/TheHockeyIndia www.youtube.com/HockeyIndiaMedia www.hockeyindia.org 04 Message from Hockey India President 05-19 20-21 22-25 Top Feature Story Feature Story Highlights Birendra Lakra Hockey India Coaching Education Pathway benefits over 1000 candidates in India 26-29 30-31 32-33 Cover Story Feature Story Feature Story Indian Men's and Women's Indian Men's Hockey Indian Women's Hockey Hockey Team Team Captain dedicating Team Captain dedicating announcement for the Olympic Medal to Olympic Medal to Olympics Covid Warriors Covid Warriors 34-35 36-37 39-45 Feature Story Feature Story Hockey India Savita Hockey India registered Member Unit Umpires Raghuprasad Activites RV and Javed Shaikh on Olympic preparations 46-49 50 51 Media Team In Focus Coverage Birthdays Gurjit Kaur Newsletter Vol. 55 (May & June 2021) Message from Hockey India President Mr. Gyanendro Ningombam Namaskar, The months of May and June were fantasc here at Hockey India. It was absolutely magnificent for Hockey India to be recognized with the Eenne Glichitch Award by the Internaonal Hockey Federaon (FIH) during the virtual conference organised as part of the 47th FIH Congress in May. We are also delighted to note that the Chairman, Managing Director and CEO of Hero MotoCorp, Dr. Pawan Munjal and the Private Secretary to the Hon’ble Chief Minister of Odisha, Shri. -

India's Missile Programme and Odisha : a Study

January - 2015 Odisha Review India's Missile Programme and Odisha : A Study Sai Biswanath Tripathy India’s missile and nuclear weapons programs First, there must be an open, uninhabited stretch have evolved as elements of its strategic response of land or water (several hundred kilometers long) to 68 years of wars and skirmishes it has fought ‘down range.’ Second, the site ideally, must allow with Pakistan and with China. Deep tensions and for longitudinal launch. The first requirement is to mistrust in the sub-continent continue unabated ensure that a malfunction during the launch stage to the present. India’s defeat by China in the 1962 does not cause damage to civilian lives and border war, probably more than any other event, property. Rocket propellant is highly explosive galvanized its leadership to build indigenous missile and if it does explode during the launch stage, and “threshold” nuclear weapons capabilities as burning fuel and metal fragments are sprayed over a credible deterrent against attack by China, and vast areas. Often, rockets fail to take off along to attain military superiority over Pakistan. the planned trajectory and have to be destroyed by the range safety officer. In this case too, the As far back as in November 1978, the· effects are so devastating that most launch sites government had set up a Committee to identify a around the world are consequently located on a site for the establishment of an instrumented test coast. range. A group of experts had surveyed a number The Bay of Bengal provides an ideal of sites, including the Sunderbans (West Bengal), stretch of sea over which missiles can be fired. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Jr.JcI6 SerIeI. VeL L. No. 42 ,'J.1IarIUr•• , 4, JJ89 V....... 14, UII (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Thirteenth Session (Eiahtb Lok Sabha) (Vol. L cOlJtaim NDs. 41 to 49);) PrIu I R.t.6. 00 (o..IGINAL BNGLISH paOCEllDINGS INCLUDBD IN ENOUSH VDSION AND ORIGINAL HlNDl nOCBBDINGS INCLUDBD IN HINDI VeRStON WILL IIIf TRBATED AS AUTHORITATIVE AND NOT TBB TRANlLATIONTHEIlBOP.] CONTENTS [Engltsh Senes, Vol L. Thirteenth Session, 198911911 (SAKA)] No 42, Thursday, May 4 19891Va/sakha 14, 1911 (SAKA) CoLUMNS Oral Answers To Questions 1-75 'Starred Questions Nos 841 to 843 and 845 to 847 Written Answers to Questions 75-342 Starred Questions Nos 844 and 848 to 860 75--88 Unstarred Questions Nos 7964 to 7994 and 70g6 to 8141 88-336 Papers Laid on the Table 343-346 Message from Ralya Sabha 346 Business Advisory Committee 347 Seventy-first Report-Adopted Matters under Rule 377 347-348 (I) Need to take urgent measures to control the spread ot 347-348 'Monkey Disease' In several parts of North and South Canara districts. Karnataka Shn G Devavaya Nark (II) Need to fill up posts In KhurOrl Road DIVISion and other 348-354 Railway stations In Orissa Shnmatl Jayantl Patnalk (III) Need to fiX remunerative pnce for mustard 349 Shn Blrbal * TI 3 Sign t marked above the name of a Member Indicates that the question was actually as«ed on the floor of the House by that Member (ij) CoLUMNS (iv) Need to open a TV centre ;1t Bhanjanagar (Orissa) 349-350 Shri Somnath Rath (v) Need to start 'Light and Sound' programme 350 on the life of Sita in Madhuhani Darbhanga and Sitamarhi in Milhlla region of Bihar Dr. -

Here. the Police Stopped Them at the Gate

[This article was originally published in serialized form on The Wall Street Journal’s India Real Time from Dec. 3 to Dec. 8, 2012.] Our story begins in 1949, two years after India became an independent nation following centuries of rule by Mughal emperors and then the British. What happened back then in the dead of night in a mosque in a northern Indian town came to define the new nation, and continues to shape the world’s largest democracy today. The legal and political drama that ensued, spanning six decades, has loomed large in the terms of five prime ministers. It has made and broken political careers, exposed the limits of the law in grappling with matters of faith, and led to violence that killed thousands. And, 20 years ago this week, Ayodhya was the scene of one of the worst incidents of inter-religious brutality in India’s history. On a spiritual level, it is a tale of efforts to define the divine in human terms. Ultimately, it poses for every Indian a question that still lingers as the country aspires to a new role as an international economic power: Are we a Hindu nation, or a nation of many equal religions? 1 CHAPTER ONE: Copyright: The British Library Board Details of an 18th century painting of Ayodhya. The Sarayu river winds its way from the Nepalese border across the plains of north India. Not long before its churning gray waters meet the mighty Ganga, it flows past the town of Ayodhya. In 1949, as it is today, Ayodhya was a quiet town of temples, narrow byways, wandering cows and the ancient, mossy walls of ashrams and shrines.