Calling the Shots Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017)

Contents Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017) 194 President’s Foreword J. Main PAPERS 195 Potential occurrence of the Long-tailed Skua subspecies Stercorarius longicaudus pallescens in Scotland C.J. McInerny & R.Y. McGowan 202 Amendments to The Scottish List: species and subspecies The Scottish Birds Records Committee 205 The status of the Pink-footed Goose at Cameron Reservoir, Fife from 1991/92 to 2015/16: the importance of regular monitoring A.W. Brown 216 Montagu’s Harrier breeding in Scotland - some observations on the historical records from the 1950s in Perthshire R.L. McMillan SHORT NOTES 221 Scotland’s Bean Geese and the spring 2017 migration C. Mitchell, L. Griffin, A. MacIver & B. Minshull 224 Scoters in Fife N. Elkins OBITUARIES 226 Sandy Anderson (1927–2017) A. Duncan & M. Gorman 227 Lance Leonard Joseph Vick (1938–2017) I. Andrews, J. Ballantyne & K. Bowler ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 229 The conservation impacts of intensifying grouse moor management P.S. Thompson & J.D. Wilson 236 NEWS AND NOTICES 241 Memories of the three St Kilda visitors in July 1956 D.I.M. Wallace, D.G. Andrew & D. Wilson 244 Where have all the Merlins gone? A lament for the Lammermuirs A.W. Barker, I.R. Poxton & A. Heavisides 251 Gannets at St Abb’s Head and Bass Rock J. Cleaver 254 BOOK REVIEWS 256 RINGERS' ROUNDUP Iain Livingstone 261 The identification of an interesting Richard’s Pipit on Fair Isle in June 2016 I.J. Andrews 266 ‘Canada Geese’ from Canada: do we see vagrants of wild birds in Scotland? J. Steele & J. -

Aim of the Game

AIM OF THE GAME DRIVEN GAME SHOOTING IN BRITAIN TODAY Game shoots around England are in a unique position to help maintain a diverse countryside where shooting and conservation work hand in hand. Slowing the decline of farmland birds is a prime example of this. Well planned game cover strips, field margins and hedgerows can not only benefit game but also provide food and shelter for many other bird species such as the twite in the Pennines and the tree sparrow and corn bunting in lowland England. Projects in Cheshire, Dorset and Somerset, under the BASC’s ‘Green Shoots’ biodiversity programme, have shown how linking shoot management with landscape scale conservation initiatives can bring even greater benefits to wildlife under increasing pressure to adapt to climate change and other challenges. The game shooters’ intimate knowledge of ‘their patch’ can also lead to the discovery of previously unknown populations of rare or threatened species as recent new records in Cheshire of dormice, barn owls and water vole bear witness. These are just some of the examples of where we can deliver more for our biodiversity and landscape. So much can be gained when we harness our collective knowledge and passion for the countryside. Dr Helen Phillips Chief Executive, Natural England 25 March 2011 2 CONTENTS 4 What is game shooting? 5 Why shoot game birds? 6 What is game? INTRODUCTION 7 How a driven day’s shooting works 11 The team behind the scenes riven game shooting has become increasingly 12 Rearing and releasing birds popular in recent decades. It is an accessible Dsport, enjoyed by many thousands of people 13 Into the wild from all walks of life. -

No 490 Autumn 2018

No 490 Autumn 2018 Photograph - Sparrowhawk at our Belvide Reserve Photographer Kevin Wardlaw This front page is sponsored by The Birder’s Store, Worcester WMBC News Is published in March, June, September and December each year to link members with each other, what’s been happening, Membership Matters current issues and forthcoming events on the birding scene in our area and further We are pleased to welcome the following new members of the club who have joined afield together with a selection of your articles and a comprehensive summary of since the last newsletter. Please note the names shown are as on the membership the recorded bird sightings in our area form but that all family members at each address are included in this welcome. Hello everyone, Mr T Baggaley of STOKE ON TRENT, Ms J Chamberlain of COVENTRY, Mr M Cottingham Here we are again, where has the last three months gone? What a summer, when folks journeyed of SOLIHULL, Mr D Daniel of BIRMINGHAM, Mr M Davies of WOLVERHAMPTON, abroad to avoid the high temperatures in Britain! But as I write the high temperatures have subsided Mr P Fletcher of WOLVERHAMPTON, Mr J Foster of FRODSHAM, Mr D Johnson of and autumn is truly on the way with birds returning on their migratory journeys and excitement and BIRMINGHAM, Mr M Khuram of BIRMINGHAM, Mr K Mallett of WHITCHURCH, Mr S O’Brien anticipation returning to our reserves. Oooh bring it on! of STAFFORD, Mr W Rotchell of RUGELEY, Mr E Whiting of LEEK, Mr R Ching of SUTTON There is lots to enjoy in this issue of your Newsletter and that is thanks entirely to your fellow members COLDFIELD, Mr D Holden of ASHBOURNE, Ms V Kirkham of CRADLEY HEATH, Mr L Stokes for sharing their birding experiences and also to the keen photographers who are increasingly sharing of WOLVERHAMPTON, Mr B Jones of WOLVERHAMPTON and Mr B Jones of their terrific shots with me without being prompted (thank you so much). -

Sustainable Driven Grouse Shooting?

Sustainable Driven Grouse Shooting? A summary of the evidence Authors Professor Simon Denny, BA, MA, PhD Dr Tracey Latham-Green, BA, MBA, PhD Professor Richard Hazenberg BA, MA, PhD Independent chair Professor James Crabbe, Wolfson College, University of Oxford July 2021 1 Date Version Updates 18.07.2021 1.0 First edition 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY THE INDEPENDENT CHAIR 7 1 INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 AIM OF THE REPORT 9 1.2 RELEVANCE AND AUDIENCE 9 1.3 THE LOGIC OF OPPOSITION TO DRIVEN GROUSE SHOOTING 10 1.4 ABOUT THE AUTHORS 12 1.5 INDEPENDENT REVIEW 13 2 SYNOPSIS 14 2.1 ECONOMICS 14 2.1.1 ECONOMIC IMPACT 1 14 2.1.2 ECONOMIC IMPACT 2 15 2.1.3 ECONOMIC IMPACT 3 16 2.1.4 ECONOMIC IMPACT 4 16 2.1.5 ECONOMIC IMPACT 5 17 2.1.6 ECONOMIC IMPACT 6 17 2.2 BIODIVERSITY 18 2.2.1 INTRODUCTION 18 2.2.2 IMPACT OF POLICY DECISIONS 19 2.2.3 RENEWABLE ENERGY 19 2.2.4 TOURISM 20 2.2.5 INTEGRATED MOORLAND MANAGEMENT 20 2.2.6 PREDATOR CONTROL 20 2.2.7 MOUNTAIN HARES 21 2.2.8 BIRDS 21 2.2.9 INVERTEBRATES 22 2.2.10 TICKS 22 2.2.11 MEDICATED GRIT 22 2.2.12 HEATHER BEETLE 23 2.2.13 STAKEHOLDERS 23 2.3 NATURAL CAPITAL AND ECOSYSTEMS 24 2.3.1 INTRODUCTION 24 2.3.2 DEFINITIONAL ISSUES 25 2.3.3 FIRE 25 2.3.4 BURNING VS. MOWING 28 2.3.5 WATER 28 2.4 SOCIAL IMPACTS 29 2.5 ALTERNATIVE USES 32 2.6 OPPOSITION TO DGS: MOTIVATIONS AND METHODS 36 3 METHODOLOGY 40 4 OVERVIEW OF DRIVEN GROUSE SHOOTING 41 4.1 THE RED GROUSE: AN INTRODUCTION 41 4.1.1 INTRODUCTION 41 4.1.2 DIFFERENT SPECIES OF GROUSE 41 4.1.3 THE RED GROUSE 42 3 4.1.4 HABITAT AND DISTRIBUTION 43 4.1.5 DISEASES 44 4.1.6 -

TIP 73 – Field Sports

TIP73 – Field Sports Contents Warning 3 Introduction 4 Game Licences 5 Food Hygiene Regulations 6 Planning Permission 8 Business Rates 9 Avian Influenza 10 Foot & Mouth Disease 11 Firearms 12 Shooting 14 Introduction to Game Shooting 15 Driven Game Shooting 16 Rough Shooting 17 Open Seasons for Game 18 Game Shoot Structures 19 Game Shoots 20 Game Shoot Income 22 Game Shoot Expenditure 24 Game Bird Rearing 25 Game Farms 27 Game Bird Losses 28 Game Birds 29 Wildfowling 32 Woodpigeon 33 Clay Pigeon Shooting 34 Laser Clay Pigeons 36 Deer Stalking 37 Deer Species 39 Hunting with Hounds 42 Foxhunting 45 Deer Hunting 46 Hunting Hares 47 Hare Coursing 48 Mink Hunting 49 Hunting Ban 50 Fishing 51 1 Fisheries 53 Fisheries – Legal 54 Particular Fish Species 55 Put & Take Fishery 56 Stocking 57 River and Loch Fishing 59 Gamekeepers 60 This area of guidance had been withheld because disclosure would prejudice the 61 assessment or collection of taxes/duties or assist tax/duty avoidance or evasion. This area of guidance had been withheld because disclosure would prejudice the 64 assessment or collection of taxes/duties or assist tax/duty avoidance or evasion. Records 68 Record Examination 70 Employer Compliance 73 VAT 74 This area of guidance had been withheld because disclosure would prejudice the 75 assessment or collection of taxes/duties or assist tax/duty avoidance or evasion. This area of guidance had been withheld because disclosure would prejudice the 77 assessment or collection of taxes/duties or assist tax/duty avoidance or evasion. This area of guidance had been withheld because disclosure would prejudice the 78 assessment or collection of taxes/duties or assist tax/duty avoidance or evasion. -

1987 Edited by T

YORK ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB REPORT Published by the York Ornithological Club 1987 Edited by T. E. Dixon, J. Pewtress, M. Leakey and D. Anderson CONTENTS COMMITTEE 4 RECORDING AREA 5 EDITORIAL 6 ORNITHOLOGICAL HIGHLIGHTS 7 STATUS OF THE RARER WADERS OCCURRING IN THE YORK AREA (1977—1957) 13 CLASSIFIED LIST 24 SPECIES OCCURRING SINCE 1966 BUT NOT IN 1987 81 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS 82 3 YORK ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB 1987 COMMITTEE HON. LIFE PRESIDENT MICHAEL CLEGG CHAIRMAN: I.R. NEWTON 9 Fairway, Clifton, York. Tel. York 653151 SECRETARY: J. PEWTRESS Youth Hostel, Canton Lane, Helmsley, York. Tel. Helmaley 70322 TREASURER: Mrs. V. WESTON, Pleasant View, The Common, Dunnington, York. Tel. York 489830 RECORDER: T.E. DIXON, The Cottage, Main Street, North Duffield, Selby. Tel. Selby 288127 ASSISTANT RECORDER: J. PEWTRESS. [1. LEAKEY, 49, Thorpe Street, Scaronoft Road, York. Tel. York 654815 R. GREGORY. EXCURSIONS SECRETARY: B. CAFFREY, 43, Broadway West, Fulford Road, York. Tel. York 652279 4 9 YORK ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB This Report has been compiled by members of the York Ornithological Club and nearly all the records have been submitted by members who are active in watching an area of about 550 square miles around York which the Club is responsible for recording. The Club has a membership of about 80 enthusiasts. It meets once a month in the Priory Street Sports and Community Centre, usually on the first Tuesday of the nonth, for a full programme of talks and discussions and for the informal exchange of information which bird watchers find invaluable. In addition, on the first Sunday of each month, there is a Club excursion to an area of ornithological interest, usually outside the recording area. -

Socio-Economic Impacts of Driven Grouse Moors in Scotland

Socio-economic and biodiversity impacts of driven grouse moors in Scotland. Part 1. Socio-economic impacts of driven grouse moors in Scotland Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Scottish Government via the Scottish Government’s Strategic Research Programme 2016-2021. The work has been undertaken by The James Hutton Institute (thorough the Policy Advice with Supporting Analysis (PAWSA) component of the Underpinning Capacity funding) and Scotland’s Rural College - SRUC (via Underpinning Policy Support funding). The views expressed in this report are those of the researchers and do not necessarily represent those of the Scottish Government or Scottish Ministers. We would like to acknowledge the advice and support of the project Steering Group: Gita Anand: Scottish Government Charles Warren: University of St Andrew Claudia Rowse: Scottish Natural Heritage Colin Shedden: British Association for Shooting and Conservation Helen Duncan: Scottish Government Hugh Dignon: Scottish Government Ian Thomson: RSPB Scotland Tim Baynes: Scottish Land & Estates (Moorland Group) Cover Photo: Photos © Mark Ewart (Lammermuirs Moorland Group) Citation: Steven Thomson, Rob Mc Morran and Jayne Glass* (2018). Socioeconomic and biodiversity impacts of driven grouse moors in Scotland: Part 1 Socio-economic impacts of driven grouse moors in Scotland. Published Online: January 2019. * Centre for Mountain Studies, Perth College, UHI i Contents Summary of the key findings from the research ................................................................................... -

BOC Newsletter

BERKSHIRE ORNITHOLOGICAL CLUB BOC Newsletter April 2020 No 80 Introduction /Conservation Corner .................................................................................................. 1 Robert Gillmor Print Auction/Richard Burness ................................................................................ 2 Trips: North Kent 25th January/Pagham Harbour 15th March ........................................................ 3/4 Beyond Birds/Bird Watching in Unprecedented Times ................................................................... 5/6 RBWM Climate Initiatives .............................................................................................................. 7 Safeguarding/Membership Matters …………... .................................................................................. 8 Puzzles/End of Grouse Shooting? ................................................................................................... 9 IDCD......................................................................................................................................... 10 Our Newbury Peregrines ............................................................................................................. 11 BirdingHighlights Apr-Jun 2019/Gallery…….…………………………………….………………………..…………..13/14 Introduction Iain Oldcorn [email protected] Welcome to the 80th BOC Newsletter. Renton explains that much Conservation activity is on hold. You again have the opportunity to bid for a signed Robert Gillmor print (edition 4 of -

Context: the Roles and Responsibilities of the Minority Leader Are Not Well-Defined

context: The roles and responsibilities of the minority leader are not well-defined . To a large extent , the functions of the minority leader are defined by tradition and custom . A minority leader from 1931 to 1939 , Representative Bertrand Snell , R-N.Y. , provided this " job description " : " He is spokesman for his party and enunciates its policies . He is required to be alert and vigilant in defense of the minority 's rights . It is his function and duty to criticize constructively the policies and programs of the majority , and to this end employ parliamentary tactics and give close attention to all proposed legislation . " question: What despcription was assigned to minority leader in part ? guessed answer: Bertrand Snell , R-N.Y. actual answer: He is spokesman for his party and enunciates its policies . context: The Earth of the early Archean ( 4,000 to 2,500 million years ago ) may have had a different tectonic style . During this time , the Earth 's crust cooled enough that rocks and continental plates beganto form . Some scientists think because the Earth was hotter , that plate tectonic activity was morevigorous than it is today , resulting in a much greater rate of recycling of crustal material . Thismay have prevented cratonisation and continent formation until the mantle cooled and convection slowed down . Others argue that the subcontinental lithospheric mantle is too buoyant to subduct and thatthe lack of Archean rocks is a function of erosion and subsequent tectonic events . question: What might have a very hot earth stopped from occurring ? guessed answer: cratonisation and continent formation actual answer: cratonisation and continent formation context: A variety of industries benefit from hunting and support hunting on economic grounds . -

Cruel and Indiscriminate: Why Scotland Must Become Snare-Free

Cruel and Indiscriminate: Why Scotland must become snare-free 1518 LACSS Snare Campaign AW.indd 1 26/09/2016 19:56 OneKind is an animal protection charity that aims to end cruelty to Scotland’s animals through campaigns, research and education. We work in partnership with others across the UK to bring our Scottish perspective to UK-wide campaigns. OneKind records snaring incidents on its dedicated SnareWatch website www.snarewatch.org to show the nature and extent of animal suffering caused by these traps. OneKind, 50 Montrose Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5DL Tel: 0131 661 9734 | [email protected] www.onekind.org The League Against Cruel Sports is a charity working to expose and end the cruelty inflicted on animals in the name of sport. In Scotland the League works to end fox hunting, ban the use of snares and campaigns against the shooting of birds for entertainment. League Against Cruel Sports Scotland, 272 Bath Street, Glasgow, G2 4JR Tel: 01483 524 250 | [email protected] www.league.org.uk #SnareFreeScotland 2 . Cruel and Indiscriminate: Why Scotland must become snare-free 1518 LACSS Snare Campaign AW.indd 2 26/09/2016 19:56 Contents 1. Executive Summary 04 2. Introduction 05 3. Preface 06 4. The trouble with snares 07 4.1 Snaring is inhumane, causing severe suffering to animals 07 4.2 Snares are indiscriminate, catching a wide range of species 09 4.3 Snares are unnecessary and counterproductive 11 4.4 There are alternatives to cruel and indiscriminate snares 12 5. Snaring incidents in Scotland 14 6. Where snaring takes place in Scotland – incident map since 2010 16 7. -

Protect Magazine Issue No4

Winter / Spring Issue January 2013 No.4 03 Bang … Goes the countryside From Criminology to Cruelty Criminologist Peter Squires talks about the cruelty involved in shooting 06 Operations Team – Special Report Updates from the field and the courtrooms in our bid to tackle wildlife crime 09 Hunt Havoc The stories of real life people affected by hunt havoc this season 2013 A lucky year for our wildlife? Page 10/11 Welcome Contents Margaret Thatcher famously stated that she was “not Regulars for turning”: well apparently Mr Cameron is. 06 League reports: From the field In 2012, the media headlines were dominated by and the courtroom the many U-turns and backtracks made by the 08 In my view … Ian Beaumont Coalition Government. For those of us in the pro- 12 Update from Parliament animal welfare corner, there were some scares and 14 Get active disappointments, but also some victories. Buzzards 16 Joe Blogs arguably benefitted the most from the Government’s vacillations, being granted reprieve from unnecessary persecution. Other species were not so lucky. The Features Government failed to act to protect circus animals, 03 Bang … Goes the Countryside despite overwhelming public support for a ban, and of From Criminology to Cruelty course, our badgers remain on death row ahead of the 05 Remembering Patrick Moore potential cull in June this year. 09 Real life victims of hunt havoc So, where does all that leave us for the year ahead? 10 2013 Year Planner Well, firstly, it would be naïve of us not to observe with concern the attitudes of some Defra ministers. -

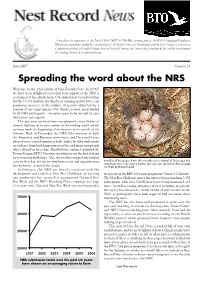

Download on Present You with the IPMR Web- a Warning Message Page At

A newsletter for supporters of the NEST RECORD SCHEME, forming part of the BTO’s Integrated Population Monitoring programme funded by a partnership of the British Trust for Ornithology and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (on behalf of English Nature, Scottish Natural Heritage, the Countryside Council for Wales, and the Environment & Heritage Service in Northern Ireland). June 2007 Number 23 Spreading the word about the NRS Welcome to the 23rd edition of Nest Record News. In 2006/7 we have been delighted to see that your support of the NRS is as strong as it has always been. Our annual nest record total has hit the 31,000 mark for the third year running and we have seen promising increases in the number of records submitted for a number of our target species. Our thanks, as ever, are extended to all NRS participants - we never cease to be amazed by your dedication and support! This past year, we have been very pleased to note flickers of interest lighting up in new corners of the birding world, which we hope mark the beginning of an increase in the profile of the Scheme. Back in December, the NRS held meetings at both the Swanwick and Braemar conferences, and Dave and I were pleased to see a good turnout at both, with a healthy enthusiasm in evidence from both long-time recorders and many new people who ‘collared’ us for a chat. Shortly before spring, I attended the Devon Regional BTO Meeting, intending to run the first of many nest-recording workshops. Alas, the weather stopped any outdoor activity that day, but we are very keen to try and organise more A well lined Treecreeper clutch.