A Common Setting for Naval Planning in Southeast Asia? Two Case Studies in Divergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leonardo Helicopters Soar in Philippine Skies

World Trade Centre, Metro Manila, Philippines 28-30 September 2016 DAILY NEWS DAY 2 29 September Leonardo helicopters soar in Philippine skies Elbit builds on M113 work New AFP projects progress Page 8 Changing course? South China Sea The Philippine Navy has ordered two AW159 Wildcat helicopters. (Photo: Leonardo Helicopters) verdict fallout Page 11 and avionics. It is no surprise that both aircraft and helicopters, the STAND 1250 the Philippine Air Force and Navy are Philippines’ strategic posture is Leonardo Helicopters has achieved extremely happy with their AW109s, interesting as it might open a number outstanding recent success in the considering them a step change in of opportunities for collaboration in the Philippine market. For example, the their capabilities.’ naval and air fields.’ Philippine Navy (PN) purchased five Leonardo enjoyed further success The company added: ‘With the navy AW109 Power aircraft and the when the PN ordered two AW159 undergoing modernisation plans, we Philippine Air Force (PAF) eight Wildcats (pictured left) in March. are ready to work with them in the field examples. The spokesperson commented: of naval guns, Heavy ADAS Daily News spoke to a ‘The AW159s were chosen after a such as the best-selling 76/62 metal Leonardo spokesperson about this. competitive selection to respond to Super Rapid gun from our Defence ‘The choice of the AW109 is very a very sophisticated anti-submarine Systems division. Furthermore, we Asia-Pacific AFV interesting because it represents the warfare (ASW) and anti-surface offer a range of ship-based radar and market analysis ambition of the Philippines to truly warfare (ASuW) requirement of the naval combat solutions that might be Page 13 upgrade their capabilities in terms of Philippine Navy. -

WATCH February 2019 Foreign News & Perspectives of the Operational Environment

community.apan.org/wg/tradoc-g2/fmso/ Foreign Military Studies Office Volume 9 Issue #2 OEWATCH February 2019 FOREIGN NEWS & PERSPECTIVES OF THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT EURASIA INDO-PACIFIC 3 Radios in the Russian Ground Forces 21 Chinese Military Launches Largest-Ever Joint Logistics 50 IRGC: Iran Can Extend Ballistic Missile Range 5 Northern Fleet Will Receive Automated C&C System Exercise 51 Turkey to Create Space Agency Integrating Air, Land and Sea 23 Luo Yuan Describes an Asymmetric Approach to Weaken 52 Iran’s Army Aviation Gets UAV Unit 6 The Inflatable Sentry the United States 53 Turkey to Sell ATAK Helicopters to the Philippines 7 The S-350 Vityaz Air Defense System 25 Military-Civil Fusion Cooperation in China Grows in the 54 Chinese Military and Commercial Cooperation with Tunisia 8 Bigger is Better: The T-80BVM Tank Modernization Field of Logistics 10 The Power Struggle for Control of Russia’s Arctic 27 Chinese Military Completes Release of New Set of Military AFRICA 11 The Arctic Will Have Prominent Role in 2019 Operational- Training Regulations 55 Anger in Sudan: Large Protests Against al-Bashir Regime Strategic Exercise “Center” 28 China Defends Xinjiang Program 56 Africa: Trouble Spots to Watch in 2019 12 Preparation for the 2019 Army International Games 29 Is Pakistan Acquiring Russian Tanks? 57 Can Businessmen Bring Peace in Gao, Mali? 13 Cossacks – Hybrid Defense Forces 30 Russia to Deploy Additional Anti-Ship Missile Batteries 58 Chinese Weapons in Rwanda 14 Update on Military Church Construction Near Japan by 2020 -

Inside This Brief Editorial Team

Inside this Brief Editorial Team Captain (Dr.) Gurpreet S Khurana ➢ Maritime Security………………………………p.6 Ms. Richa Klair ➢ Maritime Forces………………………………..p.13 ➢ Shipping, Ports and Ocean Economy.….p.21 Address ➢ Marine Enviornment………………………...p.35 National Maritime Foundation ➢ Geopolitics……………………………………….p.46 Varuna Complex, NH- 8 Airport Road New Delhi-110 010, India Email:[email protected] Acknowledgement : ‘Making Waves’ is a compilation of maritime news and news analyses drawn from national and international online sources. Drawn directly from original sources, minor editorial amendments are made by specialists on maritime affairs. It is intended for academic research, and not for commercial use. NMF expresses its gratitude to all sources of information, which are cited in this publication. IMO Focus on Maritime Security Enhancing regional maritime security in Indian Ocean region will be the focus of IONS Abe wants tighter Japan-France maritime security cooperation PH Navy now making progress in maritime security US, Vietnam Defense Chiefs Seek Increased Cooperation In Maritime Security - Pentagon Page 2 of 34 U.S. Navy plans to purchase 301 ships in the next 30 years: Report China, ASEAN begin joint naval drill Navy frigate tested China’s nerve in Taiwan Strait transit Japan makes inaugural deployment of coastguard vessel to Australia M-class frigates to receive IFF upgrade Euro naval 2018: CNIM unveils new LCX multimission landing craft for amphibious operations Page 3 of 34 India signs port partner pact with Myanmar India, Iran, -

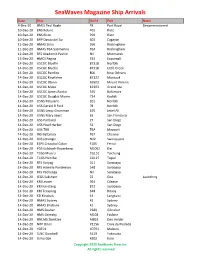

Navcall Current.Xlsx

SeaWaves Magazine Ship Arrivals Date Ship Hull # Port Notes 4-Dec-20 HMJS Paul Bogle P8 Port Royal Decommissioned 10-Dec-20 ENS Roland P01 Risto 10-Dec-20 ENS Risto P02 Risto 10-Dec-20 BRP Davao del Sur 602 Cagayan 11-Dec-20 HMAS Sirius 266 Rockingham 11-Dec-20 HMAS TBA Submarine TBA Rockingham 12-Dec-20 RFS Akademic Pashin Nil Murmansk 13-Dec-20 HMCS Regina 334 Esquimalt 14-Dec-20 USCGC Bluefin 87318 Norfolk 14-Dec-20 USCGC Bluefin 87318 Little Creek 14-Dec-20 USCGC Pamlico 800 New Orleans 14-Dec-20 USCGC Kingfisher 87322 Montauk 14-Dec-20 USCGC Obion 65503 Mount Vernon 14-Dec-20 USCGC Mako 87303 Grand Isle 14-Dec-20 USCGC James Rankin 555 Baltimore 14-Dec-20 USCGC Douglas Munro 724 Kodiak 14-Dec-20 USNS Patuxent 201 Norfolk 14-Dec-20 USS Gerald R Ford 78 Norfolk 14-Dec-20 USNS Leroy Grumman 195 Jebel Ali 14-Dec-20 USNS Mary Sears 65 San Francisco 14-Dec-20 USS Portland 27 San Diego 14-Dec-20 USS Pearl Harbor 52 San Diego 14-Dec-20 USS TBA TBA Mayport 14-Dec-20 INS Battimalv T67 Chennai 14-Dec-20 LNS Jotvingis N42 Swinoujscie 14-Dec-20 ESPS Cristobol Colon F105 Ferrol 14-Dec-20 FGS Sulzbach-Rosenberg M1062 Kiel 14-Dec-20 TCGS Miao Li CG131 Taichung 14-Dec-20 TCGS Hsin Bei CG127 Taipei 14-Dec-20 RFS Varyag 011 Surabaya 14-Dec-20 RFS Admirla Panteleyev 548 Surabaya 14-Dec-20 RFS Pechenga Nil Surabaya 14-Dec-20 ICGS Saksham 22 Goa Launching 14-Dec-20 KRI Leuser 924 Cilegon 14-Dec-20 KRI Karotang 872 Surabaya 14-Dec-20 KRI Terapang 648 Bitung 14-Dec-20 KD Kinabalu 14 Langkawi 14-Dec-20 HMAS Sydney 42 Sydney 14-Dec-20 HMAS Brisbane 41 Sydney -

Indo-Pacific

INDO-PACIFIC New Milestones in the Modernization of the Philippine Navy OE Watch Commentary: Philippines officials are calling 2018 a “banner year” for the modernization of the Philippine Navy. The accompanying excerpted article, published by the Philippine News Agency, offers an overview of some of the navy’s benchmarks reached over the past year. In short, according to the article, the navy officially entered the missile age and demonstrated an ability to sail beyond its territorial waters. On 21 November 2018, the navy’s formal entry to the missile age was marked by the firing of two newly-acquired Rafael Advanced Defense Ltd. Spike-ER (extended range) surface-to-surface missiles from three multi-purpose assault crafts (MPAC) reportedly constructed by Subic-based Propmech Corporation. Despite rough seas, guided through modern technology, both hit their targets. The Spike-ER system arrived in the Philippines in April 2018 and, having a range of eight kilometers, is the country’s first missile weapon capable of penetrating 39 inches of rolled homogeneous armor. The MPACs are high-speed naval craft capable of exceeding 40 knots. Their missions can include patrol and fire support for troops. They can be armed with missiles, and machine guns, including remote controlled .50 caliber machine guns that are ideal for anti-piracy missions. The Philippine Navy currently has only nine MPACs, with another three expected to arrive over the next 12 months; however, according to Vice Admiral Robert Empedrad, the navy’s flag officer in command, another 42 would be optimal to enhance the navy’s capabilities through swarming tactics, which would enable it to engage larger, more capable ships that pose a threat. -

Philippine Navy Anniversary

RoughTHE OFFICIALDeck GAZETTE OF THE PHILIPPINE NAVY Log• VOLUME NO. 78 • JUNE 2019 All hands for the Final st Journey of Sail Plan 2020 p. 8 The Philippine Navy: Expanding 121 Operational Reach through Multinational Engagements PHILIPPINE NAVY p. 10 PH Navy’s 1st Multi-Mission Capable Frigate ANNIVERSARY p. 25 Anti Submarine Warfare from the Air: The Role of AW159 ASW Helicopter p. 27 PN ROUGHDECKLOG 1 18 RoughDeckLog 29 Feature Articles 8 All hands for the Final Journey of Sail Plan 2020 Editorial Board 121st Philippine Navy Anniversary Theme: 10 The Philippine Navy: Expanding Operational VADM ROBERT A EMPEDRAD AFP Reach through Multinational Engagements Flag Officer In Command, Philippine Navy 12 NFC’s Stingray: Adaptive and Responsive RADM ROMMEL JUDE G ONG AFP Protecting the Seas, Naval Operations Vice Commander, Philippine Navy 15 Sea Sentinel of the East RADM LOUMER P BERNABE AFP Securing our Future 18 The Navy: A Reliable Security Partner in the Chief of Naval Staff Region COL RICARDO D PETROLA PN(M)(GSC) 22 Naval Diplomacy in a Sea of Change Assistant Chief of Naval Staff for Civil Military Contributors 24 Building Bridges China’s Int’l Fleet review Operations, N7 44 experience LCDR MARIA CHRISTINA A ROXAS PN 25 Philippine Navy’s first Multi-mission Capable Editorial Staff LT WILFREDO F NEFALAR JR PN Frigate MAJ BERYL CHARITY T BACOLCOL PN(M) Editor-In-Chief 27 Anti Submarine Warfare from the Air: The CPT JUDGE BENJAMIN R TESORO PN(M) CAPT JONATHAN V ZATA PN(GSC) Role of AW159 ASW Helicopter LT EMMANUEL C ABSALON PN 32 Editorial Assistants LT ARIESH A CLIMACOSA PN 29 Reliving a Hero’s Legacy: The Sailing Crew LCDR MARIA CHRISTINA A ROXAS PN LTJG CARLO VICTOR D MANASAN PN of BRP Conrado Yap LT RYAN H LUNA PN LTJG ALLAN LOUIE A SALVADOR PN 32 New Tracks for the Philippine Marine Corps LT RANDY P GARBO PN ENS MARIA AMANDA PRECIOUS R ZAMUCO PN 33 NAVAL CMO: Critical & Inseparable LT JOY G CARDANO PN ENS FRANCIS KENT B BATERNA PN Component of Naval Operations LT EDUARD J PABLICO PN ENS WAYNE A SOCRATES PN(RES) Technical Assistants Ms. -

The Thickening Web of Asian Security Cooperation: Deepening Defense

The Thickening Web of Asian Security Cooperation Deepening Defense Ties Among U.S. Allies and Partners in the Indo-Pacific Scott W. Harold, Derek Grossman, Brian Harding, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Gregory Poling, Jeffrey Smith, Meagan L. Smith C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3125 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0333-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photo by Japan Maritime Self Defense Force. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the turn of the century, an important trend toward new or expanded defense cooperation among U.S. -

Navy News Week 40-5

NAVY NEWS WEEK 40-5 4 October 2018 Nigeria Piracy Attack: MV Glarus update Massoel Shipping, Managers of Bulk carrier MV Glarus, attacked by pirates off Bonny, Nigeria on September 22, confirm that contact has now been made with those holding 12 crew members hostage. It is understood that all his crew are together and all are well and unharmed. The MV Glarus is now safely alongside at Port Harcourt with the remaining seven crew members on board Families are being kept in close touch with developments, the first and absolute priority being the safe release of the hostages. Massoel will not be making any further comments on operational issues as this could prejudice the safety of those being held. Source: Massoel Shipping Nigeria: High seas becoming safe, says ministry official The Federal Government through the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety (NIMASA) is doing everything to ensure safety on the high seas, a top government official has said. According to him: “The seas are sullen and the Federal Government through NIMASA is making them to become more secure for the people who sail them. “Although the African ocean is genuinely quiet at the moment, the overall political direction of the current administration is directed to settle it,” he said. Piracy, cargo theft and crew kidnap in the Gulf of Guinea are reducing in the east of Malacca, he said. The number of people affected ran into millions and are adding significantly to the numbers of migrants entering Europe by boat from Libya – itself in the throes of a chaotic and violent aftermath of the end of the Gadhafi regime. -

Deepening Interoperability a Proposal for a Combined Allied Expeditionary Strike Group Within the Indo-Pacific Region by Capt Eli J

IDEAS & ISSUES (CHASE PRIZE ESSAYS) 2019 MajGen Harold W. Chase Prize Essay Contest: First Place Deepening Interoperability A proposal for a combined allied expeditionary strike group within the Indo-Pacific region by Capt Eli J. Morales o restore readiness and en- 40,000 gallons of water from a nearby 1 hance interoperability, co- >Capt Morales is an Instructor at the supply ship. alition partners and allies MAGTF Intelligence Officer Course, Currently, the Navy and Marine Corps in the Indo-Pacific region Marine Detachment, Dam Neck, VA. are faced with a choice to maintain Tmust assemble and deploy an expedi- current levels of forward naval pres- tionary strike group (ESG) built from ence and risk breaking its amphibious the capabilities and resources of each deployment and miss Exercise COBRA force, or reduce its presence and restore coalition partner and ally. The high op- GOLD. On a separate occasion, readiness through adequate training, 2 erational tempo of the last decade has after being ordered to respond to the upgrades, and maintenance. What resulted in deferred maintenance and 2010 Haitian earthquake just one has not changed over the last decade is reduced readiness for Navy and Marine month following a seven month de- the need for Navy and Marine Corps Corps units. In 2012, after the USS ployment, the USS Bataan (LHD-5) units to establish and maintain capable Essex (LHD-2) skipped maintenance suffered a double failure of its evapora- alliances and partnerships within the to satisfy operational requirements, the tors forcing the 22nd MEU to delay Indo-Pacific region. 31st MEU was forced to cut short its rescue operations in order to take on In his farewell letter to the force, former Secretary of Defense James N. -

INDO-PACIFIC INSIGHT SERIES Philippines

INDO-PACIFIC INSIGHT SERIES Philippines: Shifting Tides in the Sulu-Celebes Sea The Sulu-Celebes Sea, commonly known as the tri-border area, has been warned as a potential “new Somalia” by Indonesian Minister for Maritime Affairs Luhut Panjaitan following a worldwide escalation in maritime kidnapping which is unparalleled in the past decade. The Philippine militants, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), have emerged as the predominant actors operating within the tri-border area, successfully kidnapping more than 50 sailors and generating roughly U.S. $7.3 million dollars in hostage revenue in the past year alone. In response, the littoral states of the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia have revitalised trilateral diplomatic efforts to strengthen a regional comprehensive framework to counter maritime piracy and kidnapping, however, there remains a failure to address many of the fundamental challenges that has so far resulted in a failure to shift the tides of the reality on the ground. Reginald Ramos, Perth USAsia Centre Volume 4, April 2017 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 The Southern Philippines 4 The Abu Sayyaf Group 5 The Philippine Government Response 6 Implications for the Broader Indo-Pacific 11 Conclusion 13 Endnotes 14 Philippines: Shifting Tides in the Sulu-Celebes Sea EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The kidnappings of Indonesian and Malaysian sailors between March and July 2016 resulted in resurgence in diplomatic efforts between the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia towards countering regional maritime piracy and kidnapping. • The Sulu-Celebes Sea, commonly known as the tri-border area, has an estimated U.S. $40 billion dollars’ worth of cargo flowing every year and maritime piracy and kidnapping threatens regional trade and stability. -

Arms Racing in Asia: the Naval Dimension

ARMS RACING IN ASIA: THE NAVAL DIMENSION Event Report Institute of Defence and 18 November 2016 Strategic Studies Nanyang Technological University Block S4, Level B4, 50 Nanyang Avenue, Singapore 639798 Tel: +65 6790 6982 | Fax: +65 6794 0617 | www.rsis.edu.sg Event Report ARMS RACING IN ASIA: THE NAVAL DIMENSION 18 November 2016 Holiday Inn Atrium, Singapore TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Section 1: Is There An Arms Race In Asia? 4 Section 2: Case Studies In Regional Arms Proliferation 38 Section 3: Expert Discussion 72 Workshop Programme 79 About the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies 82 About the S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies 83 Report of a Workshop organised by: Military Transformations Programme and Maritime Security Programme, Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS), S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore Editor Richard A. Bitzinger This report summarises the proceedings of the seminar as interpreted by the assigned rapporteurs and editors appointed by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. Participants neither reviewed nor approved this report. This workshop adheres to a variation of the Chatham House Rule. Accordingly, beyond the paper presenters cited, no other attributions have been included in this workshop report. 3 INTRODUCTION On 18 November 2016, the RSIS Military Transformations Programme (MTP), together with the RSIS Maritime Security Programme, hosted a one-day workshop on “Arms Racing in Asia: The Naval Dimension.” The workshop was held at the Holiday Inn Singapore Atrium and was run back-to-back with the Maritime Security Programme’s conference on “Navies, Coast Guards, the Maritime Community and International Stability,” held 16–17 November, also in Singapore. -

Roughdecklog

THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE PHILIPPINE NAVY • VOLUME NO. 71 • DECEMBER 2018 RoughDeckLog NEWS STORY EXERCISE PAGSISIKAP 2018: ENHANCING INTEROPERABILITY FOR THE MARITIME TERRITORY p.7 PN PARTICIPATES IN 18-DAY CAMPAIGN TO END VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN & CHILDREN p.11 FEATURE ARTICLE PN EXPANDS PRESENCE WITH MISSILE, BLUE WATER CAPABILITYp.19 SAIL PLAN CORNER THE 2018 SAIL PLAN YEAR IN REVIEW p. 26 1 PHILIPPINE NAV Y PN ROUGHDECKLOG 1 CONTENT RoughDeckLog 17 Editorial Board VADM ROBERT A EMPEDRAD AFP Flag Officer In Command, Philippine Navy 19 ABOUT THE COVER RADM ROMMEL JUDE G ONG AFP The Philippine Navy participates in the AFP-wide simultaneous Christmas Tree Lighting held on Dec. Vice Commander, Philippine Navy 03 to formally kick off the yuletide celebration. The event was made more special with the fireworks dis- RADM ERICK A KAGAOAN AFP play at the Headquarters Philippine Navy in Roxas Chief of Naval Staff Boulevard, Manila. COL RICARDO D PETROLA PN(M)(GSC) 26 Assistant Chief of Naval Staff for Civil Military VOLUME NO. 71 • DECEMBER 2018 ISSUE Operations, N7 Editorial Staff MESSAGES FEATURE ARTICLES Editor-In-Chief 4 FOIC, PN’s Message 13 NAVRESCOM @ 36: Optimizing Protecting the Role of High Performing CDR JONATHAN V ZATA PN(GSC) 5 CPF’s Message Force Multipliers in Building a Editorial Assistants 6 CPMC’s Message Strong and Credible Navy LT MARIA CHRISTINA A ROXAS PN the Seas, 14 Your Navy: Protectors of the NEWS STORIES LT ENRICO T PAYONGAYONG PN Tañon Strait LT JOY G CARDANO PN 7 Exercise PAGSISIKAP 2018: Securing 17 Serbisyong