A Rosebud Reservation Winter Count, Circa 1751-1752 to 1886-1887

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF} the Killing of Chief Crazy Horse 1St Edition Ebook Free

THE KILLING OF CHIEF CRAZY HORSE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Garnett | 9780803263307 | | | | | The Killing of Chief Crazy Horse 1st edition PDF Book Bradley had received orders that Crazy Horse was to be arrested and taken under the cover of darkness to Division Headquarters. Marks Tallahassee. Garnett's first-hand account of Crazy Horse's surrender alludes to Larrabee as the "half blood woman" who caused Crazy Horse to fall into a "domestic trap which insensibly led him by gradual steps to his destruction. Historian Walter M. The Pension Bureau regularly sent officials to the reservations where hearings were held to determine if the applicant had really served. Vanished Arizona Martha Summerhayes. Edward Kritzler. Although some compensation might be required to smooth over hurt feelings, the rejected husband was expected to accept his wife's decision. Nov 01, ISBN LOG IN. Welcome back. Little Big Man said that in the hours immediately following Crazy Horse's wounding, the camp commander had suggested the story of the guard being responsible to hide Little Big Man's role in the death of Crazy Horse and avoid any inter-clan reprisals. It goes roughly like this—Reno attacked and was driven away. His personal courage was attested to by several eye-witness Indian accounts. I found Garnett a fascinating figure from the moment I first learned of him—he was young only twenty-two when the chief was killed , he was in the very middle of events interpreting the words of the chiefs and Army officers, and he recorded things that others tried to hide or deny. -

Fort Robinson, Outpost on the Plains

Fort Robinson, Outpost on the Plains (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Roger T Grange Jr, “Fort Robinson, Outpost on the Plains,” Nebraska History 39 (1958): 191-240 Article Summary: Granger describes military activity at Fort Robinson during the Sioux Wars and includes details of garrison life in more peaceful times. Those stationed at the fort responded to the Cheyennes’ attempt to return from Indian Territory, the Cheyenne outbreak, and the Ghost Dance troubles. The fort was used for military purposes until after World War II. Note: A list of major buildings constructed at Fort Robinson 1874-1912 appears at the end of the article. Cataloging Information: Names: P H Sheridan, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, J J Saville, John W Dear, Red Cloud, Old Man Afraid of His Horses, Young Man Afraid of His Horses, Frank Appleton, J E Smith, Levi H Robinson, William Hobart Hare, Toussaint Kenssler, O C Marsh, Moses Milner (“California Joe”), Big Bat Pourier, Frank Grouard, Valentine T McGillycuddy, Ranald -

Cheyenne River Agency (See Also Upper Platte Agency)

Cheyenne River Agency (see also Upper Platte Agency) Established in 1869, this agency is sometimes called the Cheyenne Agency. The agency was located on the west bank of the Missouri River below the mouth of the Big Cheyenne River, about six miles from Fort Sully. The following Lakota bands settled at Cheyenne Agency: Miniconjou, Sihasapa, Oohenunpa, and Itazipco. Headmen at this agency included: Lone Horn, Red Shirt, White Swan, Duck, and Big Foot of the Miniconjou; Tall Mandan, Four Bears, and Rattling Ribs of the Oohenunpa; and Burnt Face, Charger, Spotted Eagle, and Bull Eagle of the Itazipco. Today the reservation is located in north-central South Dakota in Dewey and Ziebach counties. The tribal land base is 1.4 million acres with the eastern boundary being the Missouri River. Major communities include Cherry Creek, Dupree, Eagle Butte, Green Grass, Iron Lightning, Lantry, LaPlant, Red Scaffold, Ridgeview, Thunder Butte, and White Horse. Arvol Looking Horse, 19th generation keeper of the Sacred Pipe of the Great Sioux Nation, lives at Green Grass. Collections ACCESSION # DESCRIPTION LOCATION H76-105 Chief’s Certificates, 1873-1874 (Man Afraid of His Box 3568A Horses, Red Cloud, Red Dog, High Wolf) Indian Register, 1876 This register contains a census of Indians on the Cheyenne River Agency in 1876. The original is the property of the National Archives and was microfilmed at the request of the South Dakota State Historical Society in 1960. CONTENTS MF LOCATION Cheyenne River Agency Indian Register, 1876 9694 (Census Microfilm) Indian Census Rolls, 1892-1924 (M595). Because Indians on reservations were not citizens until 1974, nineteenth and early twentieth century census takers did not count Indians for congressional representation. -

The Secretary of the Interior

50'1'~~ ' ( . >~ G; HEss, } HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. { DoCUMENT _rf .'lesswn. · No. 447. AGREE.\'lENTS WITH CERTAIN INDIANS. LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR, SUBMITTING CERTAIN AGREEMENTS WITH ROSEBUD AND LOWER BRULE INDIANS FOR A CESSION OF LANDS AND MODIFICATION OP EXISTING TREATIES, TOGETHER WITH DRAFTS OF BILLS RELATING THERETO. MAY 3, 1898.-Referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs and ordered to be printed. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, T~lashington, Jlllay 3, 1898. SIR: The lndian appropriation act, approved June 7, 1897 (30 Stats., 62), provides: The Secreta.ry of the Interior is hereby authorized to negotiate, throngh an Indian inspector, with the Rosebud Indians and with the Lower Brule Indians in South Dakota for the settlement of all differences between said Indians; a.nd with the Rosebud Indians and the Lower Brule Indians, the Cheyenne River Indians in South Dakota, and with the Standing Rock Indians in North and South Dakota for aces sion of a portion of their respective reservations and for a modification of existing treaties as to the requirement of the consent of three-fourths of the male adult Indians to any treaty disposing of their lands; all agreements made to be submitted to Congress for its approval. · In compliance with the requirements of said act, United States Indian Inspector tTames McLaughlin was instructed to negotiate with the Rosebud Indians and the Lower Brule Indians for the settlement of the differences between them. The agreements concluded by him (herewith) have been considered by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and drafts of bills to ratify the same have been prepared by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Commissioner of the General I.~and Office. -

Picture-Writing

& &< -ly'^oS-^sOsf _^.<&^&£&T<*0k PICTURE-WRITING ^ OF THE AMERICAN INDIANS GARRICK MALLERY s EXTRA! T FROM THE TENTH ANNUAL REPORT OK THE BUREAU OF ETHNi >|.< K ; V WASHINGTON fiDVEK N M E N T phixtim; office 1894 / MALLEKV.] LONE-DOGS WINTER COUNT. 273 tribal division, but it has become only an expression for all those tribes whose ranges are on the prairie, and thus it is a territorial and acci- dental, not a tribular distinction. One of the Dakotas at Fort Rice spoke to the present writer of the "hostiles" as "Titons," with obviously the same idea of locality, "away on the prairie," it being well known that they were a conglomeration from several tribes. lone-dog's winter count. Fig. 183, 1800-'01.—Thirty Dakotas were killed by Crow Indians. The device consists of thirty parallel black lines in three columns, the outer lines being united. In this chart, such black lines always signify the death of Dakotas killed by their enemies. The Absaroka or Crow tribe, although belonging to the Siouau family, has nearly always been at war with the Da- kotas proper since the whites have had any knowledge of either. They are noted for the extraordinary length of their fig. 183. hair, which frequently distinguishes them in pictographs. Fig. 184, lSll-'02.—Many died of smallpox. The smallpox broke out in the tribe. The device is the head aud body of a man covered with red blotches. In this, as in all other cases where colors in this chart are mentioned, they will be found to corre- spond with PI. -

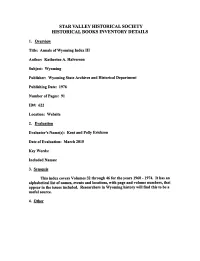

Appear in the Issues Included. Researchers in Wyoming History Will Find This to Be a Useful Source

STAR VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY HISTORICAL BOOKS INVENTORY DETAILS 1. Overview Title: Annals ofWyoming Index III Author: Katherine A. Halverson Subject: Wyoming Publisher: Wyoming State Archives and Historical Department Publishing Date: 1976 Number of Pages: 91 ID#: 622 Location: Website 2. Evaluation Evaluator's Name(s): Kent and Polly Erickson Date of Evaluation: March 2015 Key Words: Included Names: 3. Svnopsis This index covers Volumes 32 through 46 for the years 1960 - 1974. It has an alphabetical list of names, events and locations, with page and volume numbers, that appear in the issues included. Researchers in Wyoming history will find this to be a useful source. 4. Other Me^c Volume III of Wyoming VOLUMES 32 Through 46 1960 - 1974 WYOMING STATE ARCHIVES AND HISTORICAL DEPARTMENT CHEYENNE, WYOMING 19 7 6 hdcfc Volume III Mudls of Wyommg VOLUMES 32 THROUGH 46 1960 - 1974 Published By WYOMING STATE ARCHIVES AND HISTORICAL DEPARTMENT Compiled andEdited Under Supervisioh of KATHERINE A. HALVERSON Director, Historical Research andPublications Division KEY TO INDEX AND ABBREVIATIONS Adj., Adjutant Gen., General Pres., President Agii., Agriculture Gov., Governor Pvt., Private Assn., Association Govt., Government R. R., Raflroad biog., biography Hon., Honorable re, regarding, relative to Brig., Brigadier Hist., History Reg., Regiment Bros., Brothers la., Iowa Rev., Reverend Bvt, Brevet Ida., Idaho Sec., Secretary Capt., Captain lU., Illinois Sen., Senator Cav., Cavalry illus., illustration Sess., Session Co., Company Jr., Junior Sgt., Sergeant Col., Colonel Kan., Kans., Kansas S. D., So. Dak., South Dakota Colo., Colorado Lieut., Lt., Lieutenant Sr., Senior Comm., Commission Maj., Major St., Saint Cong., Congressional Mo., Missouri Supt., Superintendent Cpl., Corporal Mont., Montana T., Ten., Territory Dept., Department Mt. -

Aspects of Historical and Contemporary Oglala Lakota Belief and Ritual

TRANSMITTING SACRED KNOWLEDGE: ASPECTS OF HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY OGLALA LAKOTA BELIEF AND RITUAL David C. Posthumus Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University April 2015 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Raymond J. DeMallie, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Douglas R. Parks, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Jason B. Jackson, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Christina Snyder, Ph.D. March 12, 2015 ii Copyright © 2015 David C. Posthumus iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to many people for their friendship, encouragement, criticism, patience, and support. This work would have never been completed or possible without them. First of all I want to thank my Lakota friends and adoptive relatives for sharing their lives and deep knowledge with me. I am very thankful for your friendship, acceptance, generosity, enduring support, and for allowing me to tag along with you on your many adventures. I am eternally grateful to each and every one of you and consider you as relatives. Thank you to Robert Brave Heart, Sr. and the entire Brave Heart family; Stanley Good Voice Elk; Alvin and Steve Slow Bear; Tom Cook and Loretta Afraid of Bear; Joe Giago, Richard Giago, and Tyler Lunderman; John Gibbons and his family; and Russ and Foster “Boomer” Cournoyer. Special thanks go to Arthur Amiotte and his wife Janet Murray, the late Wilmer “Stampede” Mesteth and his wife Lisa, Richard Two Dogs and his wife Ethleen, and their families. -

Lone Dog's Winter Count: Keeping History Alive

K E EP I N G H I ST O RY A L I V E NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN LONE DOG’S WINTER COUNT: KEEPING HISTORY ALIVE Grade Level: 4–8 Time Required: Approximately 4 one-hour class periods and 2-3 homework sessions OVERVIEW OBJECTIVES Students learn about the oral culture and history-keeping In this lesson, students will: of the Nakota people, who made the Lone Dog Winter • Learn about the practice of making winter counts Count. Then they create a monthly pictograph calendar among some Native American groups. of their own to document a year of their personal history. • Study the Lone Dog Winter Count. CURRICULUM STANDARDS FOR • Learn about history keeping in an oral culture. SO CIAL STUDIES • Understand how storytellers use pictographs as National Council for the Social Studies mnemonic devices. • Provide for the study of the ways human beings view • Create a pictograph calendar of a year in their themselves in and over time. own lives. • Provide for the study of culture and cultural diversity. BACKGROUND Communities are defined by their languages, cultures, and histories. The languages of Native Americans were not traditionally written. They were only spoken, which meant that tribal histories and other important information had to be remembered by people and passed down orally from generation to generation. This is what is known as an oral tradition. Sometimes, Native communities used creative tools to help them remember their complex histories. A winter count was one such tool that certain Native American communities of the Northern Great Plains region used to help record their histories and to keep track of the passage of years. -

Before Sitting Bull

Copyright © 2010 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. KINGSLEY M. BRAY Before Sitting Bull Interpreting Hunkpapa Political History, 1750–1867 During the nineteenth century, the Hunkpapa people were the most warlike of the seven tribal divisions of the Teton Sioux, or Lakotas. Moving aggressively against their enemies, they early won a reputa- tion as resistors of the expansion of American trade and power on the Northern Great Plains. In their leader Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapas produced perhaps the single most iconic leader in the plains wars, a man deeply committed to repelling white intruders, retaining Lakota cultural verities, and resisting the imposition of the reservation system. In 1876, as the Great Sioux War convulsed the region, perhaps one- third of the Teton people gathered in the great summer encampment whose warriors went on to annihilate the Seventh United States Cav- alry command of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. While two-thirds of Lakotas had remained near their agencies on the Great Sioux Reservation, fully 70 percent of Hunkpapas answered the call of Sitting Bull at the Little Bighorn.1 A century or more of political history lay between the emergence of the Hunkpapas as an autonomous division and the seating of Sitting Bull as the Lakotas’ war leader in 1867. Probing the often fragmentary evidence of the Lakota past allows a reconstruction of the course of political events, revealing insights into the resistance that so marked Hunkpapa dealings with the United States and providing a glimpse of the last, most articulate and determined, upholder of the Hunkpapa tradition of isolationism.2 1. -

Download Press Release

Andrew Smith Gallery, Inc. Masterpieces of Photography Vida Loca Gallery at 203 W. San Francisco St., Santa Fe, NM 87501, and Andrew Smith Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibit: “Broken Treaties, Historic Witnesses” A group of historic portraits of the leading Sioux Indians who led their people during the US Government broken treaties and wars from 1865-1891. It will be shown in conjunction with "DAPL [Dakota Access Pipeline],” drawings and paintings by Santa Fe’s award- winning cartoonist and cartoon journalist Ricardo Caté. The exhibition opens Friday, December 2, 2016 with a reception and talk by Ricardo Caté from 5 to 7 p.m. The exhibit continues through January 5, 2017. “Broken Treaties, Historic Witnesses” is an important exhibit containing historic photographic portraits of the leading Native American leaders who witnessed broken treaties with the U.S. Government, displacement of their people and the desecration of Native lands. They were leaders during a time of unimaginable strife.! Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1868 The two photographs below were taken by Alexander Gardner in May 1868 at the Fort Laramie Peace Treaty. The first shows the primary groups of Sioux chiefs who signed the treaty of 1868, perhaps the most notorious of all of the broken treaties with the Sioux and still germane to the Sioux tribe. A section of the treaty reads as follows:i ARTICLE 2. The United States agrees that the following district of country, to wit, viz: commencing on the east bank of the Missouri River where the forty-sixth parallel of north latitude -

SOUTH DAKOTA - - a TRAVEL GUIDE to TRIBAL LANDS Reservations & Tribal Lands C Ontents

Native SOUTH DAKOTA - - A TRAVEL GUIDE TO TRIBAL LANDS Reservations & Tribal Lands C ONTENTS 1 RESERVATIONS & TRIBAL LANDS MAP 2 INTRODUCTION 4 RICH CULTURE AND HERITAGE 6 OcETI SAKOWIN/THE SEVEN COUNCIL FIRES 8 MILESTONES 10 VISITOR GUIDELINES 12 CHEYENNE RIVER SIOUX TRIBE 16 CROW CREEK SIOUX TRIBE 20 FLANDREAU SANTEE SIOUX TRIBE 24 LOWER BRULE SIOUX TRIBE 28 OGLALA SIOUX TRIBE 32 ROSEBUD SIOUX TRIBE 36 SISSETON WAHPETON OYATE 40 STANDING ROCK SIOUX TRIBE 44 YANKTON SIOUX TRIBE 48 LANDSCAPES & LANDMARKS 50 NATIVE AMERICAN ART 60 POWWOWS & CELEBRATIONS RESERVATIONS TRAILS 64 TRIBAL CASINOS 66 TRIBAL CONTACT LISTINGS 1 CHEYENNE RIVER INDIAN N10 ATIVE AMERICAN RESERVATION SCENIC BYWAY 2 CROW CREEK INDIAN RESERVATION 11 OYATE TRAIL 3 FLANDREAU SANTEE INDIAN RESERVATION 4 LOWER BRULE INDIAN RESERVATION 5 PINE RIDGE INDIAN RESERVATION 6 ROSEBUD INDIAN RESERVATION 7 SISSETON-WAHPETON OYATE TRIBAL LANDS 8 STANDING ROCK INDIAN RESERVATION 9 YANKTON TrIBAL LANDS Pine Ridge Indian Reservation Introduction WELCOME to the land of the Dakota, word “nadouessioux,” which is believed Lakota and Nakota. There are nine to be a derogatory term meaning “little Native American tribes that call snakes.” The name may have resulted South Dakota home, and each of them from a history of territorial conflicts has a unique story to tell. Working between the Sioux and the Ojibwas. together, they welcome visitors into People of the Great Sioux Nation their communities in order to educate prefer the terms Dakota, Nakota and and to share. When visiting Native Lakota when referring to themselves communities, you will experience as a people and a nation. -

Copy of RCJ Special Sales 2020

CategoryName EntrantName Place Automotive Auto Detailer Mr. Detailz Winner Color Mystique Second Place Unique Auto Groom Runner Up Rapid City Paintless Dent Repair T&T Detailing & Sales Auto Glass Repair and Replacement Frontier Auto Glass Winner Kustomz Truck & Auto Second Place Safelite AutoGlass Runner Up Dakotaland Autoglass Rapid Auto Glass Auto Parts Store Black Hills Tire Winner O'Reilly Auto Parts Second Place Kustomz Truck & Auto Runner Up Sturdevant's Auto Parts NAPA Auto Parts - Prairie Auto Parts of Rapid City Auto Repair (Collision) Kustomz Truck & Auto Winner Roy's Westside Auto Body Second Place Mel's Auto Body & Glass - East Runner Up Abra Auto Body Repair of America S.A.C Auto Body Great Western Tire Inc. Auto Repair (Mechanical) Black Hills Tire Winner Bob's Auto Service Second Place Great Western Tire Inc Runner Up Wicked Wrenches Whipple Racing Products Brake Shop Black Hills Tire Winner Great Western Tire Second Place Advanced Auto Repair Inc. Runner Up Wicked Wrenches Bert's Brakes & Automotive Car Audio Sound Pro Winner Kustomz Truck & Auto Second Place Mobile Fx Runner Up The Audio Shop RC Great Western Tire Car Wash Super Clean Tunnel Wash Winner Rapid Wash Second Place Parkway Car Wash Runner Up Big D Oil Co Zaug Wash Muffler Shop Black Hills Tire Winner Exhaust Pros Second Place TMA - Tire Muffler Alignment - East Runner Up Great Western Tire Hills Tire and Supply New Auto Dealer Liberty Superstores Winner Courtesy Subaru Second Place McKie Ford Lincoln Runner Up Denny Menholt Rapid Chevrolet Denny Menholt Toyota Granite Buick GMC Rushmore Honda Granite Nissan Hersrud's Of Belle Fourche, Inc.