Economics of Music Streaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Top 65 Women Business Influencers 04TOP 65 Women Business Influencers TABLE of Contents 01 Why

Top 65 Women Business influencers 04TOP 65 Women Business Influencers TABLE OF CONTENTs 01 Why . 3 02 Concept . 3 03 A Brief Disclaimer . 4 04 Top 65 Women Business Influencers . 5 The idea behind the creation of this list was simple; we wanted one unified document that ranked influencers based on the WHY same scale. Currently, if someone was interested that their rankings are the ultimate in answering the question of, rundown of who to follow. However, in “who are the top women business today’s hyper-data driven world, that’s influencers today?” they’d have an no longer acceptable. Consumers have extraordinarily difficult time coming grown hungrier for proof, as they’re 01 up with an accurate picture of the no longer willing to accept a list from field. Googling this question brings a reputable source with no rhyme or up a number of results . Some from reason to how it was compiled; and as Hubspot, Salesforce, Forbes, and other consumers ourselves, we were struck respectable outlets; however each of with the same problems . them suffers from a singular issue . These issues ultimately lead us None are organized in any discernible to create our own Top 65 Women way . They simply tell readers that Business Influencers list, which is their list is the most comprehensive ranked carefully by the same set of group of influencers assembled, and metrics across the board . During the creation of this list, the singular most important question we had to answer was, what’s the best indicator of an influencer? Unfortunately there’s no easy answer; CONCEPT arguments can be made for a wide variety of metrics. -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 22.06.2019

22.06.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 25 - 1 11151 5 I Don't Care . Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber 222121 2 Old Town Road . Lil Nas X 333241 7 Someone You Loved . Lewis Capaldi 44471 2 Vossi Bop . Stormzy 555112 Bad Guy . Billie Eilish 67764 Hold Me While You Wait . Lewis Capaldi 78896 SOS . Avicii feat. Aloe Blacc 8 --- --- 1N8 No Guidance . Chris Brown feat. Drake 99939 Cross Me . Ed Sheeran feat. Chance The Rapper & PnB Rock 10 11 11 1110 All Day And Night . Jax Jones & Martin Solveig pres. Europa . 11 10 10 69 If I Can't Have You . Shawn Mendes 12 --- 14 309 Grace . Lewis Capaldi 13 15 --- 213 Shine Girl . MoStack feat. Stormzy 14 13 --- 213 Never Really Over . Katy Perry 15 24 39 315 Wish You Well . Sigala & Becky Hill 16 17 13 73 Me! . Taylor Swift feat. Brendon Urie Of Panic! At The Disco 17 6 6 132 Piece Of Your Heart . Meduza feat. Goodboys 18 --- --- 1N18 Mad Love . Mabel 19 --- --- 1N19 Stinking Rich . MoStack feat. Dave & J Hus 20 --- --- 1N20 Heaven . Avicii . 21 22 18 318 The London . Young Thug feat. J. Cole & Travi$ Scott 22 --- --- 1N22 Shockwave . Liam Gallagher 23 30 31 323 One Touch . Jesse Glynne & Jax Jones 24 27 23 618 Guten Tag . Hardy Caprio & DigDa T 25 14 --- 214 What Do You Mean . Skepta feat. J Hus 26 43 48 1526 Ladbroke Grove . AJ Tracey 27 34 29 327 Easier . 5 Seconds Of Summer 28 18 47 518 Greaze Mode . -

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Louis Armstrong Kate Nash Sonny & Cher Matt Cardle Animals Cliff Richard Manfred Mann Craid David Petula Clark Ray Charles Roy Orbison HearSay Kings Of Leon Ne-Yo Jamelia Shayne Ward Holly Valance Georgie Fame Bobby Darin Paul Weller Vengaboys Scouting For Girls Cilla Black Avicii Beach Boys Spencer Davis Group Blue Plan B Kelly Clarkson Britney Spears Queen Basshunter Black Eyed Peas Bobby Vee Freda Payne Doobie Brothers Gerry & The Pacemakers Marmalade Doris Day JLS Evanescence Katy Perry Christina Aguilera Ronetts Anastacia Liberty X James Morrison Jeff Beck Snoop Dogg Chubby Checker Copyright QOD Page 1/28 Host's Master Artist List for Game 2 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Smokey Robinson Lovin' Spoonfull Troggs Ben Heanow Dion Warwick Avons James Brown Snow Patrol Little Richard Diana Ross Ronetts Tom Jones Dean Martin Gladys Knight Estelle Kid Rock Evanescence Mamas & The Papas Fats Domino Lulu Anastacia Good Charlotte Craid David Coral Ne-Yo Emili Sande Mumford & Son Lenny Kravitz Fatboy Slim Justin Timberlake Lily Allen Doris Day Spencer Davis Group Who Stevie Wonder Queen KT Tunstall Scissor Sisters Buddy Holly Nickelback Shayne Ward Kinks Brenda Lee Andy Williams Holly Valance Temptations Searchers Britney Spears Shirley Bassey The Fray Copyright QOD Page 2/28 Host's Master Artist List for Game 3 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. -

About the Speakers

5-7 Oct 2013 – Bali, Indonesia PRESS (PRESS) CONTACT (CONTACT-OVERVIEW.HTML) Home (index.html) The Summit (about-overview.html) The Host Economy (host.html) Sponsors (sponsors.html) Registration (registration.html) Delegates (delegates.html) Summit Overview (about- Program Highlights Speakers About Previous Summits overview.html) (program.html) (about.html) About the Speakers The APEC CEO Summit will feature an exciting interactive program that covers the key issues affecting the Asia Pacific. As in past Summits, we look forward to the participation of many APEC Leaders taking part in the program. In addition, global states persons, thought leaders and CEO's of international companies will be taking part in robust and dynamic discussions. 'We anticipate the participation of the following APEC Leaders in the Summit program.' Speaker Line-up Tony Abbott Sebastián Piñera Xi Jinping Prime Minister Australia President of Chile President of China Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Shinzō Abe Park Geun-Hye President of Indonesia Prime Minister of Japan President of Korea Najib Razak Enrique Peña Nieto John Key Prime Minister of Malaysia President of Mexico Prime Minister of New Zealand Ollanta Humala Benigno Aquino III Vladimir Putin President of Peru President of the Philippines President of Russia Lee Hsien Loong John Kerry Prime Minister of Singapore Secretary of State of the United States of America Business and Thought Leaders Cher Wang Christopher A. Viehbacher Dennis Nally Chairperson of HTC Corporation and Chief Executive Officer of Sanofi Chairman -

Absolute Radio Brand Guidelines 2014.Indd

The style guide Key features Page 2 Our brand identity is key to our future Names Colour Channel bar success. As our business grows and The name of the master brand is To the extent that visual content Our brand icons set must allow for easy becomes more diverse (for example Absolute Radio and should never be features colour other than black and navigation between the channels in the with the addition of new stations), and shortened to Absolute. white, the primary colour shall be Absolute Radio portfolio. as digital becomes a more and more • It’s important as we extend our purple. • Moving our audience around within important channel, it is important that brand to new audiences and new Absolute Radio channels is central we present the brand in a recognisable channels that people understand to our strategy. and consistent way. what we do. We’re proud to be a • The ‘portfolio’ versions of the logo radio brand but we’re a modern This page summarises the key elements have been introduced for use within radio brand, that understands radio of our identity system (and also strongly Absolute Radio branded is content, not channel. any changes, where elements have environments to make navigation evolved). easy and fun. Discovery Icon • They are secondary elements and Absolute Radio has one central icon, must not stand alone. the ‘Discovery Icon’. • Having an icon is important to help people navigate app stores (which they do with pattern recognition). • We need to use our icon consistently and persistently to make sure it becomes indelibly associated with our brand. -

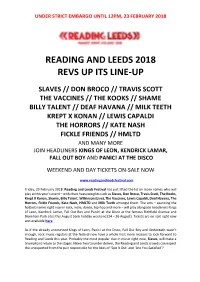

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

Maas360 and Ios

MaaS360 and iOS A comprehensive guide to Apple iOS Management Table of Contents Introduction Prerequisites Basics and Terminology Integrating MaaS360 with Apple’s Deployment Programs Deployment Settings Enrollment: Manual Enrollment Enrollment: Streamlined Apple Configurator Device View Policy App Management Frequently Asked Questions "Apple’s unified management framework in iOS gives you the best of both worlds: IT is able to configure, manage, and secure devices and control the corporate data flowing through them, while at the same time users are empowered to do great work with the devices they love to use.” -Apple Business “Managing Devices and Corporate Data on iOS” Guide IBM Security / © 2019 IBM Corporation 3 Types of iOS Management “Supervision gives your organization more control iOS supports 3 “styles” of management that will over the iOS, iPadOS, and tvOS devices you own, determine the MDM capabilities on the device. allowing restrictions such as disabling AirDrop or Apple Music, or placing the device in Single App Standard – an out-of-the-box device with no additional Mode. It also provides additional device configurations. Would be enrolled over-the-air via a Safari configurations and features, so you can do things URL or the MaaS360 agent. like silently install apps and filter web usage via a global proxy, to ensure that users’ web traffic stays Supervised – Supervision unlocks the full management within the organization’s guidelines. capabilities available on iOS. Can be automated via the Apple streamlined enrollment program or enabled manually By default, iOS, iPadOS, and tvOS devices are not via Apple configurator. Supervision of an existing device supervised. -

Legal-Process Guidelines for Law Enforcement

Legal Process Guidelines Government & Law Enforcement within the United States These guidelines are provided for use by government and law enforcement agencies within the United States when seeking information from Apple Inc. (“Apple”) about customers of Apple’s devices, products and services. Apple will update these Guidelines as necessary. All other requests for information regarding Apple customers, including customer questions about information disclosure, should be directed to https://www.apple.com/privacy/contact/. These Guidelines do not apply to requests made by government and law enforcement agencies outside the United States to Apple’s relevant local entities. For government and law enforcement information requests, Apple complies with the laws pertaining to global entities that control our data and we provide details as legally required. For all requests from government and law enforcement agencies within the United States for content, with the exception of emergency circumstances (defined in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act 1986, as amended), Apple will only provide content in response to a search issued upon a showing of probable cause, or customer consent. All requests from government and law enforcement agencies outside of the United States for content, with the exception of emergency circumstances (defined below in Emergency Requests), must comply with applicable laws, including the United States Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA). A request under a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty or the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (“CLOUD Act”) is in compliance with ECPA. Apple will provide customer content, as it exists in the customer’s account, only in response to such legally valid process. -

Minutes of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Justice for Equitable Life Policyholders Held on 10Th November 2014 at 4.30Pm in Committee Room 17, House of Commons

Minutes of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Justice for Equitable Life Policyholders Held on 10th November 2014 at 4.30pm In Committee Room 17, House of Commons Present: Bob Blackman MP (co-chair), Fabian Hamilton MP (co-chair), Stephen Lloyd MP (secretary), Alistair Burt MP, Andrea Leadsom MP, Andrew George MP, Andrew Jones MP, Dame Anne Begg MP, Annette Brooke MP, Bob Neill MP, Caroline Spelman MP, Claire Perry MP, Heather Wheeler MP, Ivan Lewis MP, Jason McCartney MP, Jenny Willott MP, John Leech MP, Julian Lewis MP, Mark Field MP, Mary Glindon MP, Mary Macleod MP, Mike Hancock MP, Mike Thornton MP, Paul Uppal MP, Sir Peter Bottomley MP, Philip Hollobone MP, Rebecca Harris MP, Richard Harrington MP and Tessa Munt MP. Paul Braithwaite (EMAG), Alex Henney (EMAG) and Paul Weir (EMAG). The staff of Clive Betts MP, David Davis MP, Desmond Swayne MP, Elizabeth Truss MP, Fiona Bruce MP, Guy Opperman MP, Harriett Baldwin MP, Iain Stewart MP, John Baron MP, Michael Fallon MP and Stephen O'Brien MP • Andrew Jones (Con, Harrogate and Knaresborough) (AJ) chaired the meeting for the election of officers. All officers had indicated willingness to stand for re-election. AJ proposed the election of Bob Blackman (Con, Harrow East) (BB) and Fabian Hamilton (Lab, Leeds North East) (FH) as Co-Chairs, this was seconded by Alistair Burt (Con, North East Bedfordshire) (AB) and approved by the Group. The election of Stephen Lloyd (Lib Dem, Eastbourne) (SL) as Secretary was proposed by AJ and seconded by Dame Anne Begg (Lab, Aberdeen South) and approved by the Group. -

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent Vs. Sign to a Label: Artist's Point of View

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to a Label: Artist’s Point of View Sampo Winberg Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in International Business 2018 Abstract Date 22.5.2018 Author(s) Sampo Winberg Degree programme International Business Report/thesis title Number of pages Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to and appendix pages a Label: Artist’s Point of View 58 + 6 The mark of an artist making it in music industry, throughout its relatively short history, has always been a record deal. It is a ticket to fame and seen as the only way to make a living with your music. Most artist would accept a record deal without hesitating. Being an artist myself I fall into the same category, at least before conducting this research. As we know record labels tend to take a decent chunk of artists’ revenues. Goal of this the- sis is to find out ways how a modern-day artist makes money, and can it be done so that it would be better to remain as an independent artist. What is the difference in volume that artist needs without a label vs. with a label? Can you get enough exposure and make enough money that you can manage without a record label? Technology has been and still is the single most important thing when it comes to the evo- lution of the music industry. New innovations are made possible by constant technological development and they’ve revolutionized the industry many times. First it was vinyl, then CD, MTV, Napster, iTunes, Spotify etc. -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 28.12.2019

28.12.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 52 - 1 1 --- --- 1N1 1 I Love Sausage Rolls . LadBaby 22342 Own It . Stormzy feat. Ed Sheeran & Burna Boy 34252 Before You Go . Lewis Capaldi 43472 Don't Start Now . Dua Lipa 5713922 Last Christmas . Wham! 6 --- --- 1N6 Audacity . Stormzy feat. Headie One 75575 Roxanne . Arizona Zervas 8681052 All I Want For Christmas Is You . Mariah Carey 9 --- --- 1N9 Lessons . Stormzy 10 1 1 201 11 Dance Monkey . Tones And I . 11 8 14 48 River . Ellie Goulding 12 11 --- 211 Adore You . Harry Styles 13 9 6 53 Everything I Wanted . Billie Eilish 14 14 22 1082 Fairytale Of New York . The Pogues & Kirsty McColl 15 12 11 296 Bruises . Lewis Capaldi 16 16 26 751 2 Merry Christmas Everyone . Shakin' Stevens 17 15 23 781 5 Do They Know It's Christmas ? . Band Aid 18 47 55 518 Watermelon Sugar . Harry Styles 19 24 39 3910 Step Into Christmas . Elton John 20 17 12 312 Blinding Lights . The Weeknd . 21 19 18 1314 Hot Girl Bummer . Blackbear 22 21 15 93 Lose You To Love Me . Selena Gomez 23 23 20 1020 Pump It Up . Endor 24 25 32 347 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas . Michael Bublé 25 29 43 283 One More Sleep . Leona Lewis 26 35 40 426 Falling . Trevor Daniel 27 51 --- 3210 Lucid Dreams . Juice WRLD 28 31 33 2813 Santa Tell Me . Ariana Grande 29 34 44 804 I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday .