Thomas Von Aquin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemplation and the Human Animal in the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Contemplation and the Human Animal in the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas Edyta M. Imai Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Imai, Edyta M., "Contemplation and the Human Animal in the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas" (2011). Dissertations. 205. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/205 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Edyta M. Imai LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO CONTEMPLATION AND THE HUMAN ANIMAL IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF ST. THOMAS AQUINAS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY BY EDYTA M. IMAI CHICAGO IL DECEMBER 2011 Copyright by Edyta M. Imai, 2011 All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE: CONTEMPLATION AND NATURAL APPETITES 30 CHAPTER TWO: SENSATION AND CONTEMPLATION 104 CHAPTER THREE: DESIRE AND CONTEMPLATION 166 CHAPTER FOUR: DELIGHT AND CONTEMPLATION 230 BIBLIOGRAPHY 291 VITA 303 iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ST Summa theologiae SCG Summa contra gentiles QDV Quaestiones disputatae de veritate QDA Quaestiones disputatae de anima In Boetii de Trin. In Librum Boetii de Trinitate Expositio In DA Sententia libri De anima In NE Sententia libri Ethicorum In Met Commentarium in XII libros Metaphysicorum In Ph Commentarium in VIII libros Physicorum SENT Commentarium in quatuor libros Sententiarum iv INTRODUCTION In this dissertation I examine the manner in which – according to Thomas Aquinas - the operations of the sensitive soul contribute to contemplation. -

Chronology of Anselm's Life

APPENDIX A Chronology of Anselm's Life (See Eadmer; Southern; Charlesworth, pp. 8-21.) 1033 Born at Aosta in Burgundy c.1053 His mother dies; 'the ship ofhis heart, having lost its anchor, drifted among the waves of the world' 1056 Quarrels with his father; leaves home and wan ders through Burgundy and France 1060 Enters the Benedictine monastery of Bee in Normandy 1063 Succeeds Lanfranc as Prior of Bee 1076 Monologion 1077-8 Proslogion 1078 Succeeds Herluin as Abbot of Bee 1080-5 de Grammatico, de Veritate, de Libertate Arbitrii 1085-90 de Casu Diaboli 1092-4 Epistola de Incamatione Verbi 1093 Reluctantly enthroned as Archbishop of Canter bury 1094--8 Cur Deus Homo 1097 Exiled by William II; journeys to Rome, and stays at Lyons 1099-1100 de Conceptu Virginali 1100 Death of William II; Anselm recalled by Henry I 1102 de Processione Spiritus Sancti 1103 Exiled by Henry I; at Lyons 1106 Returns to England 1106-7 Epistola de Sacrijicio Azymi et Fermentati; de Sacra mentis Ecclesiae 1107-8 de Concordia ?1108 de Potestate 1109 Dies, 21 April ?1163 Canonised 87 APPENDIX B Anselm's Reductio It may be helpful to set out more rigorously the interpretation of Anselm's reductio which is explained informally on pp. 12-15 above. In the main the formalisation follows Lemmon; but there are several points needing explanation: (i) Abbreviations: 'b' for 'The Fool' 'xUy' for 'x understands "y"' 'xMy' for 'y is in x's understanding' 'xi: P' for 'x can imagine that P' 'Ex' for 'x exists in reality' 'xGy' for 'x is greater than y' 'xi : Fy' for 'x can imagine something F'. -

Thomas Handbuch

Thomas Handbuch Thomas Handbuch herausgegeben von Volker Leppin Mohr Siebeck Die Theologen-Handbücher im Verlag Mohr Siebeck werden herausgegeben von Albrecht Beutel ISBN 978-3-16-150084-8 (Leinen) ISBN 978-3-16-149230-3 (Broschur) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2016 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. www.mohr.de Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlags unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikro- verfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Das Buch wurde von Gulde-Druck in Tübingen aus der Minion Pro und der Syntax gesetzt, auf alterungsbe ständiges Werkdruck papier gedruckt und von der Buchbinderei Spinner in Otters- weier gebunden. Den Umschlag gestaltete Uli Gleis in Tübingen. Abbildung: Carlo Crivelli, Saint Thomas Aquinas © The National Gallery, London. Vorwort Nun muss ich nicht mehr die Frage fürchten: „Und, wie steht es mit dem Thomas Handbuch?“ Noch so freundlich vorgetragen, erinnerte sie am Rande von Tagun- gen und Gremiensitzungen daran, dass ich, als ich vor über zehn Jahren die Auf- gabe übernahm, ein Nachschlagewerk zu der Zentralgestalt der mittelalterlichen Theologie vorzubereiten, nicht geahnt hatte, in welche Untiefen mich dieses Pro- jekt bringen würde. Die lange Dauer hat mir vor Augen geführt, wie schwierig es, zumal in Zeiten von Jubiläumsvorbereitungen und Reformations dekaden, ist, als Forscher den Spagat zwischen Neuzeit und Mittelalter zu wagen. Zu den vielfäl- tigen Anforderungen im Vorfeld des Jahres 2017 kamen von mir selbst hervor- gerufene Ablenkungen hinzu – nicht zuletzt der Wechsel von Jena nach Tübingen im Jahre 2010 mit allen Aufregungen, die dergleichen mit sich bringt. -

Adoro Te Devote

Adoro Te Devote Eucharistic Adoration in the Spirit of St Thomas Aquinas St Saviour’s Church, Dominick St (D1) Some of the best loved Eucharistic hymns - Adoro Te Devote, Tantum Ergo, Panis Angelicus - were written by one man, the Dominican Friar St. Thomas Aquinas. The Dominican Friars of St. Saviour's Priory, which has been in existence for nearly 800 years, will mark the 50th International Eucharistic Congress by inviting renowned preachers to explain the rich delights of these Eucharistic hymns, all in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, exposed for our veneration. The preachers include Wojciech Giertych OP, the Pope's personal theologian; Paul Murray OP, a celebrated spiritual writer; John Harris OP, well-known for his ministry to young people; and Terence Crotty OP, a Scripture scholar. The evening events will also include music and silent adoration, and will conclude with the Office of Compline, sung by the Dominican community, and the ancient tradition of the Salve Regina procession. Finally, on Saturday, St Saviour's will host a day-long festival of Eucharistic adoration. Come and join us, as we contemplate the source and summit of our faith, 'in which Christ is received, the memory of His Passion is renewed, the soul is filled with grace, and the pledge of future glory is given to us' (St Thomas Aquinas). Mon 11 June, 8pm Fri 15 June, 8pm Wojciech Giertych OP (Papal Theologian) John Harris OP Pange Lingua Verbum Supernum Prodiens Sat 16 June, 11am-6pm Tues 12 June, 8pm Eucharistic Adoration in St Saviour's Church Paul Murray OP (Professor of Spiritual Theology, Angelicum) Adoro Te Devote Thurs 14 June, 8pm Terence Crotty OP Lauda Sion . -

1 the Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas

The Summa Theologiae and the Reformed Traditions Christoph Schwöbel 1. Luther and Thomas Aquinas: A Conflict over Authority? On 10 December 1520 at the Elster Gate of Wittenberg, Martin Luther burned his copy of the papal bull Exsurge domine, issued by pope Leo X on 15 June of that year, demanding of Luther to retract 41 errors from his writings. The time for Luther to react obediently within 60 days had expired on that date. The book burning was a response to the burning of Luther’s works which his adversary Johannes Eck had staged in a number of cities. Johann Agricola, Luther’s student and president of the Paedagogium of the University, who had organized the event at the Elster Gate, also got hold of a copy of the books of canon law which was similarly committed to the flames. Following contemporary testimonies it is probable that Agricola had also tried to collect copies of works of scholastic theology for the burning, most notably the Summa Theologiae. However, the search proved unsuccessful and the Summa was not burned alongside the papal bull since the Wittenberg theologians – Martin Luther arguably among them – did not want to relinquish their copies.1 The event seems paradigmatic of the attitude of the early Protestant Reformers to the Summa and its author. In Luther’s writings we find relatively frequent references to Thomas Aquinas, although not exact quotations.2 With regard to the person of Thomas Luther could gleefully report on the girth of Thomas Aquinas, including the much-repeated story that he could eat a whole goose in one go and that a hole had to be cut into his table to allow him to sit at the table at all.3 At the same time Luther could also relate several times and in different contexts in his table talks how Thomas at the time of his death experienced such grave spiritual temptations that he could not hold out against the devil until he confounded him by embracing his Bible, saying: “I believe what is written in this book.”4 At least on some occasions Luther 1 Cf. -

Politics and Collective Action in Thomas Aquinas's on Kingship

Anselm Spindler Politics and collective action in Thomas Aquinas's on kingship Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Spindler, Anselm (2018) Politics and collective action in Thomas Aquinas's on kingship. Journal of the History of Philosophy. ISSN 0022-5053 © 2018 Journal of the History of Philosophy, Inc. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/87076/ Available in LSE Research Online: March 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Politics and Collective Action in Thomas Aquinas's On Kingship There is currently a vibrant debate in philosophy about the nature of collective intentionality and collective action. However, these topics are rarely explored in detail from the perspective of the history of philosophy. And if reference is made to the history of philosophy, it is mostly to antique authors like Plato1 or to modern authors such as Hobbes2, Rousseau3, or Kant4 – although it has been appreciated that these were important issues in the Middle Ages as well.5 Therefore, I would like to contribute a little bit to a broadened understanding of the history of these concepts by exploring the political philosophy of Thomas Aquinas. -

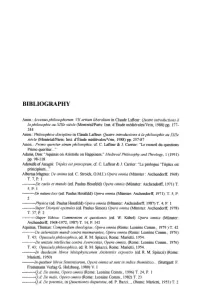

BIBLIOGRAPHY A

BIBLIOGRAPHY Anon.:Accessus philosophorum: VII artium liberalium in ClaudeLafleur: Quatre introductions a la philosophie au XIIle steele (Montreal/Paris: Inst. d'Etude medievales/Vrin, 1988) pp. 177- 244 Anon. : Philosophica disciplina in ClaudeLafleur: Quatre introductions ala phi/osophie au XIIle steele (Montreal/Paris: lust. d'Etude medievales/Vrin, 1988) pp. 257-87 Anon.: Primo queritur utrum philosophia , cf. C. Lafleur & 1. Carrier: "Le recueil du questions Primo queritur..." Adams, Don: "Aquinas on Aristotleon Happiness," Medieval Philosophy and Theology, 1(1991) pp. 98-118 Adenulfe of Anagni: Triplex est principium , cf. C. Lafleur & J. Carrier: "Le prologue 'Triplex est principium..." AIbertus Magnus: De anima (ed. C. Stroick, O.MJ.) Opera omnia (Miinster: Aschendorff, 1968) T. 7, P. I ----------De caelo et mundo (ed. PaulusHossfeld) Opera omnia (Miinster:Aschendorff, 1971) T. 5, P. I ---De natura loci (ed. PaulusHossfeld) Opera omnia (Munster: Aschendorff, 1971) T. 5, P. 2 ----------Physica (ed. Paulus Hossfeld) Opera omnia (Miinster: Aschendorff, 1987) T. 4, P. I ---------Super Dionysii epistulas (ed. Paulus Simon) Opera omnia (Miinster: Aschendorff, 1978) T. 37, P. 2 ----------Super Ethica. Commentem et questiones (ed. W. Kiibel) Opera omnia (Munster: Aschendorff, 1968-1972, 1987) T. 14, P. I-II Aquinas, Thomas: Compendium theologiae, Opera omnia (Rome:Leonine Comm., 1979) T. 42 ------De aeternitate mundi contra murmurantes, Opera omnia (Rome:Leonine Comm., 1976) T. 43; Opuscula philosophica, ed. R. M. Spiazzi, Rome: Marietti, 1954. ----------De unitate inte//ectus contra A verroistas, Opera omnia , (Rome: Leonine Comm., 1976) T. 43; Opuscula phi/o sophica, ed. R. M. Spiazzi, Rome: Marietti, 1954. ---------In duodecim libros Metaphysicorum Aristotelis expositio (ed. -

Liber Hymnorum. the Latin Hymns of the Lutheran Church

!"#$!" % $&'()*'$!" +, -'$$.!/ 0'&1!& 6)$ !"#$#5( !--'(2!* 3&!)) 45&$ /',(!, #( CONTENTS Page Hymn CALENDAR, OR TABLE OF FIXED FEASTS xi TABLE OF HYMN ASSIGNMENTS 7eir Yearly Course xii Proper & Common of Saints xiv HYMNS IN ENGLISH #. 7e Daily O8ce [9] 9 ##. Times & Seasons [:9] ;< ###. Church Dedication [=>] =< #1. Proper of Saints [?@] == 1. Common of Saints [>=] @A 1#. Hymns of the Procession & Mass [99:] >9 1##. Additional Songs & Chants [9;:] >= 1###. Spiritual Songs [9:>] 9BA HYMNS IN LATIN #. 7e Daily O8ce [9=:] 9 ##. Times & Seasons [9@>] ;< ###. Church Dedication [;99] =< #1. Proper of Saints [;9=] == 1. Common of Saints [;<=] @A 1#. Hymns of the Procession & Mass [;?9] >9 1##. Additional Songs & Chants [;@:] >= 1###. Spiritual Songs [;A@] 9BA INDICES #. First Lines with Hymn Number & Author [;>@] ##. Authors with Hymn Numbers [:B9] ###. First Lines with Melody Numbers [:B:] #1. Comparison of the Melodies among the Sources [:B=] THE HYMNS IN THEIR YEARLY COURSE Numbers refer to the same hymn in both the English & the Latin sections. THE DAILY OFFICE From the Octave of Epiphany to Invocavit; from Trinity Sunday to Advent. Hymn Hymn Compl. Te lucis ante terminum . 9 On Saturdays a!er the Su%rages may be Matins Nocte surgentes. ;–: sung the hymn Serva Deus verbum tuum . >= Te Deum . ;: Ferial Vespers— Lauds Ecce jam noctis . < Sun. Lucis Creator optime. >–9B or Nocte surgentes. ;–: Mon. Immense cæli Conditor . 99–9; Prime Jam lucis ordo sidere. .= Tues. Telluris ingens Conditor. 9:–9< Terce Nunc sancte nobis Spiritus . .? Wed. Cæli Deus sanctissime . 9=–9? Sext Rector potens verax Deus . .@ 7ur. Magnæ Deus potentiæ. 9@–9A None Rerum Deus tenax vigor. .A Fri. -

The Domain of Logic According to Saint Thomas Aquinas the Domain of Logic According to Saint Thomas Aquinas

THE DOMAIN OF LOGIC ACCORDING TO SAINT THOMAS AQUINAS THE DOMAIN OF LOGIC ACCORDING TO SAINT THOMAS AQUINAS by ROBERT W. SCHMIDT, S.]. Xavier University, Cincinnati • THE HAGUE MARTINUS NI]HOFF 1966 ISBN 978-94-015-0367-9 ISBN 978-94-015-0939-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-015-0939-8 Copyright 1966 by Martinus NijhoJf, The Hague, Netherlands. All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form. Imprimi potest: John R. Connery, 5.J. Provincial, Chicago Province January 7, 1966 N ihil obstat: Daniel E. Pilarczyk, 5.T.D., Ph. L., Censor January 7, 1966 Imprimatur: Most Rev. Paul F. Leibold Vicar General, Archdiocese of Cincinnati January 15, 1966 PREFACE Ever since philosophy became conscious of itself, there has been a problem of the relations between the real world which philosophy sought to understand and explain, and the thought by which it sought to explain it. It was found that thought had certain requirements and conditions of its own. If the real world was to be understood through thought, there was a question whether thought and the real correspond ed in all respects, and therefore whether they had the same conditions and laws, or whether some of these were peculiar to thought alone. For the solution of this problem it was necessary to study thought and the process of knowing and the conditions which the manner of know ing placed upon our interpretation of the real. With a consciousness of the peculiarities of thought and of its laws, philosophers could then more surely make use of it to arrive at the knowledge of the real world which they were seeking, without danger of reading into the real what is peculiar to thought. -

Gerald Near—List of Music for Organ, Organ Transcriptions, Organ and Instruments, Harpsichord and Hymns with Annotations Prepared by Steven Egler, Revised March 2017

Gerald Near—List of Music for Organ, Organ Transcriptions, Organ and Instruments, Harpsichord and Hymns with Annotations Prepared by Steven Egler, Revised March 2017 AE=Aureole Editions MSM=MorningStar Music Publishers OP=Out of Print Organ Solo Carillon on a Ukranian Bell Carol. AE, 2006. AE151. Dedicated to Dr. Steven Egler. Note: Based upon the familiar “Carol of the Bells.” Chantworks: Organ Music for the Church Year based upon Gregorian Chant melodies. Set I—Advent, Christmas, Epiphany. AE, 1997. AE42. 1. “Veni, Veni Emmanuel” (“O Come, O Come Emmanuel”)-- Advent 2. “Conditor Alme Siderum” (“Creator of the Stars of Night”)-- Advent 3. “Vox Clara Ecce Intonat” (“Hark! A Thrilling Voice Is Sounding”)--Advent 4. “Divinum Mysterium” (“Of the Father’s Love Begotten”)-- Christmas 5. “O Solis Ortus Cardine” (“From east to west, from shore to shore”)--Christmas 6. “Christe, Redemptor Omnium” (“Jesu, Redeemer of the world”)—Christmas; Partita: Theme & Four Variations 7. “A Sola Magnarum Urbium” (“O More Than Mighty Cities Known”)--Epiphany Set II—Lent, Passiontide, Easter. AE, 1998. AE43. 1. “Audi, Benigne Conditor” (“O Master of the world, give ear”)-- Lent 2. “Jam, Christe, Sol Justitæ” (“Now, Christ, Thou Sun of righteousness”)—Lent 3. “Ex More Docti Mystico” (“The fast, as taught by holy lore”)— Lent 2 4. “Vexilla Regis Prodeunt” (“The royal banners forward go”)— Passiontide 5. “Pange Lingua Gloriosi” (“Sing my tongue the glorious battle”)—Passiontide 6. “Lustris Sex Qui Jam Peractic” (“Thirty years among us dwelling”)—Passiontide 7. “Ad Cœnam Agni Providi” (“The Lamb’s high banquet we await”)—Easter 8. “Aurora Lucis Rutilat” (“Light’s glittering morn bedecks the sky”)—Easter Set III—Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity, Corpus Christi, Morning, Evening. -

A Latin-To-Maltese Literary and Religious Translator Ivan Said*

Fr Albert M. Grech O.P. (1883-1942): A Latin-to-Maltese literary and religious translator Ivan Said* The 1930s are considered to be a crucial era for modern Maltese: In 1934, the British Colonial Government recognised Maltese as an official language, together with English, ending once and for all the great Language Question which had dragged on since the previous century. Thus, Maltese became one of the official languages of the colony’s administration, used throughout the Law Courts and the Civil Service at the expense of the long-established Italian language. From the literary point of view, this decade gave us some of the best Maltese classics, both in prose and in poetry, particularly in 1938, the year our national poet Dun Karm completed his magnum opus Il-Jien u Lilhinn Minnu, Karmenu Fr Albert M. Grech O.P. Vassallo published his book of poems Nirien and the year when Ġino Muscat Azzopardi, Ġużè Aquilina, Ġużè Ellul Mercer and Ivo Muscat Azzopardi published their novels in Maltese. It was during this same year that Fr Albert M. Grech O.P., a Dominican Latinist, finished the translation from Latin to Maltese of the first two books of L-Enejjija, Vergil’s Aeneid. Two years earlier, this fervent lover of Maltese published L-Għanjiet dwar l-Ewkaristija, a translation from Latin of St Thomas Aquinas’ five Eucharistic hymns. Who was Fr Albert M. Grech O.P. Carlo Grech was born in Sliema on 7th October 1883 to Mikiel and Karmena Xuereb. On 22nd November 1898 he joined the Dominican Order and took the name of Albert. -

Chrīstum Ducem

Verbum Supernum: Lauds Hymn for the Feast of Corpus Christi composed by St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) translated by Jeffrey C. Kalb, Jr. Verbum supernum prodiens, The Word supernal going forth, nec Patris linquens dexteram, yet seated at His Father’s right, ad opus suum exiens, now going out for deeds of worth, venit ad vitae vesperam. had come to life’s own vesper light. In mortem a discipulo, By Judas to His rivals sold, suis tradendus aemulis, by rivals given to the grave, prius in vitae ferculo He first in dish of Life untold se tradidit discipulis. Himself to His disciples gave. Quibus sub bina specie His Flesh and Blood He did prepare carnem dedit et sanguinem, concealed beneath a twofold sign, ut duplicis substantiae that man entire might take for fare totum cibaret hominem. His Substance human and divine. Se nascens dedit socium, When born, Himself as Friend He gave, convescens in edulium when supping, as both Food and Lord, se, moriens in pretium, when dying, as the Price to save, se regnans dat in praemium. but reigning, He is our Reward. O salutaris Hostia, O saving Victim here confessed, quae caeli pandis ostium, Who gate of Heaven open laid, bella premunt hostilia: on us, by hostile wars oppressed, da robur, fer auxilium. bestow Thy strength, confer Thine aid. Uni trinoque Domino, To Lord Almighty, One and Three, sit sempiterna gloria, let praise and glory ever tend! qui vitam sine termino May God so grant that we may see nobis donet in patria. a life in Heaven without end.