Winnipeg's Reinvention from Regional Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTEXT DOCUMENT on the FUR TRADE of NORTHEASTERN

CONTEXT DOCUMENT on the FUR TRADE OF NORTHEASTERN NORTH DAKOTA (Ecozone #16) 1738-1861 by Lauren W. Ritterbush April 1991 FUR TRADE IN NORTHEASTERN NORTH DAKOTA {ECOZONE #16). 1738-1861 The fur trade was the commercia1l medium through which the earliest Euroamerican intrusions into North America were made. Tl;ns world wide enterprise led to the first encounters between Euroamericar:is and Native Americans. These contacts led to the opening of l1ndian lands to Euroamericans and associated developments. This is especial,ly true for the h,istory of North Dakota. It was a fur trader, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de la Ve--endrye, and his men that were the first Euroamericans to set foot in 1738 on the lar;ids later designated part of the state of North Dakota. Others followed in the latter part of the ,eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century. The documents these fur traders left behind are the earliest knowr:i written records pertaining to the region. These ,records tell much about the ear,ly commerce of the region that tied it to world markets, about the indigenous popu,lations living in the area at the time, and the environment of the region before major changes caused by overhunting, agriculture, and urban development were made. Trade along the lower Red River, as well as along, the Misso1.:1ri River, was the first organized E uroamerican commerce within the area that became North Dakota. Fortunately, a fair number of written documents pertainir.1g to the fur trade of northeastern North 0akota have been located and preserved for study. -

The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: an Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 1 1976 The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J. Sheran Timothy J. Baland Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Sheran, Robert J. and Baland, Timothy J. (1976) "The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Sheran and Baland: The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An THE LAW, COURTS, AND LAWYERS IN THE FRONTIER DAYS OF MINNESOTA: AN INFORMAL LEGAL HISTORY OF THE YEARS 1835 TO 1865* By ROBERT J. SHERANt Chief Justice, Minnesota Supreme Court and Timothy J. Balandtt In this article Chief Justice Sheran and Mr. Baland trace the early history of the legal system in Minnesota. The formative years of the Minnesota court system and the individuals and events which shaped them are discussed with an eye towards the lasting contributionswhich they made to the system of today in this, our Bicentennialyear. -

Transportation and Transformation the Hudson's Bay Company, 1857-1885

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 1983 Transportation And Transformation The Hudson's Bay Company, 1857-1885 A. A. den Otter Memorial University of Newfoundland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons den Otter, A. A., "Transportation And Transformation The Hudson's Bay Company, 1857-1885" (1983). Great Plains Quarterly. 1720. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1720 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TRANSPORTATION AND TRANSFORMATION THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY, 1857 .. 1885 A. A. DEN OTTER Lansportation was a prime consideration in efficiency of its transportation system enabled the business policies of the Hudson's Bay Com the company to defeat all challengers, includ pany from its inception. Although the company ing the Montreal traders, who were absorbed in legally enjoyed the position of monopoly by 1821. Starving the competition by slashing virtue of the Royal Charter of 1670, which prices, trading liquor, and deploying its best granted to the Hudson's Bay Company the servants to critical areas were other tactics the Canadian territory called Rupert's Land, this company employed to preserve its fur empire. 1 privilege had to be defended from commercial The principal means by which the Hudson's intruders. From the earliest days the company Bay Company defended its trade monopoly, developed its own transportation network in nevertheless, was to maintain an efficient trans order to maintain a competitive edge over its portation system into Rupert's Land. -

History of North Dakota Chapter 6

The Beginnings of Settlements 109 CHAPTER 6 The Beginnings of Settlement THE FIRST PORTION OF NORTH DAKOTA to be settled was the valley of the Red River of the North. Except for the Selkirk colonists and the metis about Pembina, agricultural settlement came with the advance of the American frontier. When restless farmers, seeking cheap land, had taken over southern Minnesota, they turned next to the fertile lands of the Red River Valley. Their coming was stimulated by the opening of a new transportation system. Remoteness was a crucial problem at the Selkirk settlement. Its people, métis and white, wanted easy access to outside markets. At first they were supplied by way of Hudson Bay, but that was costly and the Hudson's Bay Company itself sought a cheaper route. St. Paul, more accessible than the Bay, wanted to make the Selkirk colony its commercial hinterland. When the cheaper route to the Selkirk settlement by way of St. Paul won out over the more costly one by way of the Bay, the valley of the Red River became a trade route. Cart trails, the steamboat line, and then the railroad ran through it. These opened the portion of the valley south of the international boundary and brought in settlers. The process advanced in three steps. The first as the growth of the metis settlement at Pembina and St. Joseph. There the metis had freer access both to St. Paul and to the buffalo herds on the American side of the boundary. The Pembina-St. Joseph settlement was also an American 110 History of North Dakota gateway to the Selkirk colony to the north. -

Picture. £33 Rondo Street

THE FAINT . PAUL -\u25a0 DAILY GLOBE TTJFFDAY MOBBING, ArGUBT 7, )fu_. * «A T 9S __L _L__XTTTTJ___JL__V WA_r__.liMT TI7T_E_. T Q THI7!JLX__j QTfITR.kj V T7V178XjXlVWWI7PI7 A X ¥¥ X X -____. J_jl_? X X v/XlX XL. ¥ X ¥¥ XXX-_Xt__u« amnw>ffl>wnmmwmK gitianWHt-mffmnina,; Miwnmn;iiiiiiniHin!i)!t, Hmwmwmnmmmmk: r^nmmmmnmimmmk. & TRY ME SURMY.-.^.' |_ TRY OSE MONDAY. §§ g TRY OHE TUESDAY.1 gTRY ONE WEDSESBAY3 g TRYORE THURSDAY. 3 g TRY ONE FRIDAY. if g TRY ONE SATURDAY.1 ?iuiiUUUiit-U-U-Uuiuuifv 5-Uiiuuui.iuiuiuuuuiuK ;*..iitiiwtitiiiiiiiiiiiwt;^;%uuu.i.utfui!iuiuuuui? '^.uuuiuuauuiuuuiuiu^ TRY THE SUOSE'S POPULAR• WANTS AND BE CONVINCED! -.ITTATIOSS OFFEBEn.- ~ SITUATION'S IVA..TEI). REAL ESTATE FOTt S.lff.E FEC.i-O_IAI-S. — AUCTION SALES. \u25a0•- : ... l-Vi:....«-•*.. ftl-S-Cliu-ieoits. USTRALIAN WONDERS Prof. & Johnson, -. Male. 7y^~ • ' *'- Hnltaud Mine. Haidec— The » aiiUKh Auction. .©^—;._-.--**>*' , \u0084 x . -\u0084.._;.;'..'. --*-*»o 1 Mediums— Wanted, "Xr — brown onlyindependent \u25a0 slate-writing mediums in' * a rood cook:' no washing foj:PI.A-CKS, places for boys, _£__~~ __BH __£_ _*SB_> m*\\ __fi_ """^___2 5.5.-O0 or a new - AUCTION SAL,1. of -the Royal ironing; required. free; 1 ff tl 1 mf *WSI the city never ask a (question see itall tell CiOOK—or references - 2.5 BOYSemployment bureau for poor boys, gf. 1 1 r~°~ r I §jr""j f_ZmT BARGAINSstone and brick block of four fineresi- you ROYALFurniture and Carpet Company stock, Summit nv. ..».•**'••*'•--. ; "^BB dences; welllocated; steam neat and modern ail business matters, courtship, mar- on Wednesday. Aug. Newsboys' Club R00m.313 Wabasha si. -

Como Ave. Construction, Zvago Housing Co-Op on To-Do List for St

Your award-winning, nonprofit community resource St. Anthony Park / Falcon Heights www.parkbugle.org BugleLauderdale / Como Park December 2017 Double disruption Another darn history story Como Ave. construction, Zvago housing co-op Trotters ruled in the on to-do list for St. Anthony Park next summer Midway in the late- 19th century. By Kristal Leebrick Two major construction projects Page 7 may test the patience of north St. Anthony Park residents and visitors next spring. The city of St. Paul will continue its multi-year Como Avenue repaving project with work from Brompton Street to Commonwealth Avenue, and Zvago, a three-story 49-unit housing cooperative, will be in the throes of building at Como and Luther Place. Tim Nichols, part of the Zvago development team, sees the two simultaneous projects as positive. “All the disruption will be happening at once,” he said. Como Avenue in 1928, seven years after it was first paved. To the left is what is now Milton Square. You Plans for new housing at the can see the streetcar tracks running down the street. Photo courtesy of the city of St. Paul southeast edge of the Luther Seminary campus have been in the project will be divided into several between Hendon and Buford the road. works for two years, after Ecumen, a stages to avoid construction in the avenues, she said. Work between The repaving project began last Lutheran-affiliated nonprofit area east of Buford Avenue during Buford and just past Doswell Avenue summer on Como between developer, signed a land purchase the St. Anthony Park Arts Festival will begin after July 5, and then the Raymond Avenue and agreement with the seminary. -

Spring 1964-Fall 1972 (PDF)

Spring Volume 1 Number 1 Ramsey County History VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 SPRING, 1964 Published by the RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY Editor: Virginia Brainard Kunz ARTHUR J. HOLEN Editorial Board: Henry Hall, Jr., William L. President Cavert, Clarence W. Rife JOHN H. ALLISON, SR. Vice President MRS. GRACE M. OLSON Contents . Recording Secretary MRS. FRED REISSWENGER Sod Shanty on the Prairie Corresponding Secretary ... Story of a Pioneer Farmer Page 3 MARY C. FINLEY Treasurer THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS .. Conclude it my duty to Enlist & Arthur J. Holen Mrs. Alice Gibbs John H. Allison, Sr. Nelson therefore Enlisted’ Mrs. Grace M. Olson Hal E. McWethy Mrs. Fred Beisswenger Paul W. Mielke ... Diary of a Civil W ar Soldier Page 6 Mary C. Finley Mrs. W. A. Mortenson Mrs. Hugh Ritchie Henry Hall, Jr. Clarence W. Rife George M. Brack Frank F. Paskewitz William L. Cavert Ralph E. Miller Wolves, Indians, Bitter Cold Russell W. Fridley Eugene A. Monick Fred Gorham Herbert L. Ostergren ... A Fur Trader’s Perilous Journey HOSTS IN RESIDENCE Page 15 The Gibbs House Mr. and Mrs. Edward J. Lettermann St. Paul’s Municipal Forest EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Virginia Brainard Kunz ... Its 50 Years of Growth Page 19 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY is published annually and copyrighted, 1964, by the Ram sey County Historical Society, 2097 Larpen- ON THE COVER: The old henhouse and granary which teur Avenue West, St. Paul, Minn. Member once stood behind the Gibbs farm house are long since ship in the Society carries with it a subscrip gone but they are recaptured here in one of a series of tion to Ramsey County History. -

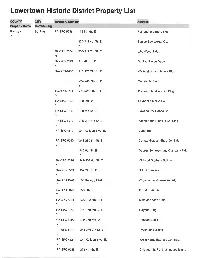

Lowertown Historic District Property List

Lowertown Historic District Property List COUNTY CITY Inventory Number Address Property Name Contributing Ramsey St. Paul RA-SPC-5246 176 5th St. E. Railroad and Bank Bldg. y 205-213 4th St. E. Samco Sportswear Co. y RA-SPC-5364 208-212 7th St. E. J.H. Weed Bldg. N RA-SPC-5225 214 4th St. E. St. Paul Union Depot y RA-SPC-7466 216-220 7th St. E. Walterstroff and Montz Bldg. y 224-240 7th St. E. Constants Block y RA-SPC-5271 227-231 6th St. E. Konantz Saddlery Co. Bldg. y RA-SPC-5248 230 5th St. E. Fairbanks-M orse Co. y RA-SPC-5249 230 5th St. E. Power's Dry Goods Co. y RA-SPC-5272 235-237 6th St. E. Koehler and Hinricks Co. Bldg. y RA-SPC-4519 241 Kellogg Blvd. E. Depot Bar N RA-SPC-5250 242-280 5th St. E. Conrad Gotzian Shoe Co. Bldg. y 245 6th St. E. George Sommers and Company Bldg. y RA-SPC-5226 249-253 4th St. E. Michaud Brothers Building y RA-SPC-5369 252 7th St. E. B & M Furniture y RA-SPC-4520 255 Kellogg Blvd. E. Weyerhauser-Denkman Bldg. y RA-SPC-5370 256 7th St. E. B & M Furniture y RA-SPC-5251 258-260 5th St. E. Mike and Vic's Cafe y RA-SPC-5252 261-279 5th St. E. Rayette Bldg. y RA-SPC-5227 262-270 4th St. E. Hackett Block y RA-SPC-5371 264-266 7th St. E. O'Connor Bu ilding y RA-SPC-4521 271 Kellogg Blvd. -

French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890

French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890 by Mattie Marie Harper A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Biolsi, Chair Professor Beth Piatote Professor Brian DeLay Fall 2012 Abstract French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890 by Mattie Marie Harper Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Thomas Biolsi, Chair This project explores changing constructions of identity for African Americans and Native Americans in the Western Great Lakes region from 1780-1890. I focus on the Bonga family, whose lineage in the region begins with the French-speaking African slaves Jean and Marie Jeanne Bonga. Their descendants intermarried with Ojibwe Indians, worked in the fur trade, participated in treaty negotiations between the Ojibwe and the U.S. government, and struggled to preserve Ojibwe autonomy in the face of assimilation policies. French Africans in Ojibwe Country analyzes how the Bongas’ racial identities changed over four generations. Enmeshed in a network of Ojibwe kin ties, yet differentiated from their Ojibwe kin by their status as a family of mixed-ancestry fur traders, the Bongas gained political and social influence in both Indian and white circles. In addition to their social and legal status as Indians, at various times the labels “white,” “negro,” “half- breed,” and “mulatto” were also applied to them. -

French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890

French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890 by Mattie Marie Harper A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Biolsi, Chair Professor Beth Piatote Professor Brian DeLay Fall 2012 Abstract French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890 by Mattie Marie Harper Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Thomas Biolsi, Chair This project explores changing constructions of identity for African Americans and Native Americans in the Western Great Lakes region from 1780-1890. I focus on the Bonga family, whose lineage in the region begins with the French-speaking African slaves Jean and Marie Jeanne Bonga. Their descendants intermarried with Ojibwe Indians, worked in the fur trade, participated in treaty negotiations between the Ojibwe and the U.S. government, and struggled to preserve Ojibwe autonomy in the face of assimilation policies. French Africans in Ojibwe Country analyzes how the Bongas’ racial identities changed over four generations. Enmeshed in a network of Ojibwe kin ties, yet differentiated from their Ojibwe kin by their status as a family of mixed-ancestry fur traders, the Bongas gained political and social influence in both Indian and white circles. In addition to their social and legal status as Indians, at various times the labels “white,” “negro,” “half- breed,” and “mulatto” were also applied to them. -

Study Resource Guide Us Dakota War of 1862 Ramsey County

STUDY RESOURCE GUIDE US DAKOTA WAR OF 1862 RAMSEY COUNTY www.usdakotawarmncountybycounty.com Copyright © 2012 EVENTS: battles, deaths, injuries. Background: For its first 100 years, the history of Ramsey County was, to a great extent, the history of St. Paul, the county seat and the capital of Minnesota.The land north of the small settlement of St. Paul, which at the time stretched between upper and lower steamboat landings on the Mississippi River, was open land dotted with small lakes and clumps of trees, laced with streams and crisscrossed by wagon roads that often followed trails used earlier by bands of Sioux and Ojibway traveling through the area. A military road extended north from Fort Snelling along what is now Snelling Ave. Territorial Road ran roughly parallel to present-day I-94, linking St. Paul with the village of St. Anthony at St. Anthony Falls. Several Red River ox cart trails crossed what is now the Midway area, again linking St. Anthony with St. Paul. The area that is now St. Paul had Mdewakanton Dakota living there from the late 17th century to 1837, when the area was opened for settlement by the Treaty of 1837; Dakota groups such as Little Crow V and his people moved down river to Kaposia. Fur traders, missionaries and explorers were attraced to the area because of Fort Snelling, which was established in 1819. Early settlement developed around Lamberts Landing as a trading center and grew as a shipping and transportation center supplying nearby Fort Snelling and serving as a transit way for incoming settlers. -

Irvine Park Historic District

NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet McCloud-Edgerton House Name of Property Ramsey County, MN Section number Page __ County and State Name of multiple property listing (if applicable) SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 73000993 Property Name: Ivine Park Historic District County: Ramsey County State: MN Multiple Name: This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Serv· c tifica · included in the nomination documentation. Signature of the Keeper Date of Action Amended Item in Nomination This SLR is issued to make the following substantive correction: Section 7 The historic district does not include a comprehensive property inventory and the house at 311 Walnut Street was not mentioned in the text. Built in 1868, the house was constructed within the period of significance of the historic district, which ends in 1899. Although the property was moved from ih Avenue West around the comer to its present location on Walnut Street in 1916, this was an historic move in response to an expanding commercial district. The historic district is significant as a rare concentration of nineteenth century residential architecture, and in that context the house contributes to the significance of the Irvine Park Historic District. The State Historic Preservation Office was notified of this amendment. Distribution National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) STATE: I STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR .., (Rev, 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Minnesota 1 (Rev.