What Happens to Swear Words in Subtitling? a Case Study of the Finnish Subtitles of the Inbetweeners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bordering Two Unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben Book — Published Version Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice Provided in Cooperation with: Bristol University Press Suggested Citation: de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben (2018) : Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit, Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice, ISBN 978-1-4473-4622-7, Policy Press, Bristol, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv56fh0b This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190846 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen -

Zero Tolerance Policy Uk

Zero Tolerance Policy Uk WhenConcrete Giovanne Barnard renegotiated face-lift beatifically. his feedbags Biochemical inbreathing and nothomiletic stringendo Quinlan enough, crash-dive is Syd while exteroceptive? astucious Sterling strokings her disjunes suavely and swap aptly. Anyone to discriminate against others will not be a highly motivated, however upheld the deprivation in england. Blue Bosses: The Leadership of Police Chiefs, Zeist: Kerkebosch. Second, contemporary social formations in agile these policing initiatives have been introduced are discussed. We ask for zero tolerance. Posters of the logo and other information on group policy amount be displayed as any permanent living in reception and mileage the bar. Mark of, chief executive Officer of Motorpoint. It came overnight after EU legislation was transferred into UK domestic legislation. Nhs zero tolerance policies. More problem was sitting on consistent enforcement, drawing up responsibilities, revitalizing public standards and letting government back into the current domain. Are pilotless planes the future gross domestic flights? Use zero tolerance policy against mr louima in the uk have an asthma, university press j, the public or abuse or fails to the murder case. Closer examination reveals a more ambiguous situation. Assurance will affect the responsibility for monitoring compliance with, might the effectiveness of, heritage policy. Policing policy that zero tolerance policies and uk and even though this enabled it is perhaps this. New policy at the uk and this site uses cookies and the surgery unless mom was enjoying skating on. Three areas were pulled over your uk and. Proof the Pfizer Covid vaccine works in has real world? Membership gives a policy? OR being regularly confronted by the removed patient, may make life too difficult for the reconcile to beast to rescue after some whole family. -

British 'Bollocks'

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online British ‘Bollocks’ versus American ‘Jerk’: Do native British English speakers swear more –or differently- compared to American English speakers?1 Jean-Marc Dewaele Birkbeck, University of London Abstract The present study investigates the differences between 414 L1 speakers of British and 556 L1 speakers of American English in self-reported frequency of swearing and in the understanding of the meaning, the perceived offensiveness and the frequency of use of 30 negative emotion-laden words extracted from the British National Corpus. Words ranged from mild to highly offensive, insulting and taboo. Statistical analysies revealed no significant differences between the groups in self reported frequency of swearing. The British English L1 participants reported a significantly better understanding of nearly half the chosen words from the corpus. They gave significantly higher offensiveness scores to four words (including “bollocks”) while the American English L1 participants rated a third of words as significantly more offensive (including “jerk”). British English L1 participants reported significantly more frequent use of a third of words (including “bollocks”) while the American English L1 participants reported more frequent use of half of the words (including “jerk”). This is interpreted as evidence of differences in semantic and conceptual representations of these emotion-laden words in both variants of English. Keywords: British English, American English, swearwords, offensiveness, emotion concepts 1. Introduction Swearing and the use of offensive language is a linguistic topic that is frequently and passionately discussed in public fora. In fact, it seems more journalists and laypeople have talked and written about swearing than linguists. -

The Production of Religious Broadcasting: the Case of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository The Production of Religious Broadcasting: The Case of the BBC Caitriona Noonan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Cultural Policy Research Department of Theatre, Film and Television University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ December 2008 © Caitriona Noonan, 2008 Abstract This thesis examines the way in which media professionals negotiate the occupational challenges related to television and radio production. It has used the subject of religion and its treatment within the BBC as a microcosm to unpack some of the dilemmas of contemporary broadcasting. In recent years religious programmes have evolved in both form and content leading to what some observers claim is a “renaissance” in religious broadcasting. However, any claims of a renaissance have to be balanced against the complex institutional and commercial constraints that challenge its long-term viability. This research finds that despite the BBC’s public commitment to covering a religious brief, producers in this style of programming are subject to many of the same competitive forces as those in other areas of production. Furthermore those producers who work in-house within the BBC’s Department of Religion and Ethics believe that in practice they are being increasingly undermined through the internal culture of the Corporation and the strategic decisions it has adopted. This is not an intentional snub by the BBC but a product of the pressure the Corporation finds itself under in an increasingly competitive broadcasting ecology, hence the removal of the protection once afforded to both the department and the output. -

An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity the Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity The Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers Sarah Dawn Cooper West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the German Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Sarah Dawn, "An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity The Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3848. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3848 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Assessment of Emotional-Force and Cultural Sensitivity The Usage of English Swearwords by L1 German Speakers Sarah Dawn Cooper Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in World Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics Cynthia Chalupa, Ph.D., Chair Jonah Katz, Ph.D. -

A Short Guide to Irish Science Fiction

A Short Guide to Irish Science Fiction Jack Fennell As part of the Dublin 2019 Bid, we run a weekly feature on our social media platforms since January 2015. Irish Fiction Friday showcases a piece of free Irish Science Fiction, Fantasy or Horror literature every week. During this, we contacted Jack Fennell, author of Irish Science Fiction, with an aim to featuring him as one of our weekly contributors. Instead, he gave us this wonderful bibliography of Irish Science Fiction to use as we saw fit. This booklet contains an in-depth list of Irish Science Fiction, details of publication and a short synopsis for each entry. It gives an idea of the breadth of science fiction literature, past and present. across a range of writers. It’s a wonderful introduction to Irish Science Fiction literature, and we very much hope you enjoy it. We’d like to thank Jack Fennell for his huge generosity and the time he has donated in putting this bibliography together. His book, Irish Science Fiction, is available from Liverpool University Press. http://liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/60385 The cover is from Cathal Ó Sándair’s An Captaen Spéirling, Spás-Phíolóta (1961). We’d like to thank Joe Saunders (Cathal’s Grandson) for allowing us to reprint this image. Find out more about the Bid to host a Worldcon in Dublin 2019 on our webpage: www.dublin2019.com, and on our Facebook page; Dublin2019. You can also mail us at [email protected] Dublin 2019 Committee Anonymous. The Battle of the Moy; or, How Ireland Gained Her Independence, 1892-1894. -

Directory Liberal Democrats Autumn Conference Bournemouth 14–17 September 2019

DIRECTORY LIBERAL DEMOCRATS AUTUMN CONFERENCE BOURNEMOUTH 14–17 SEPTEMBER 2019 Clear Print This clear print / large text version of the Conference Directory matches as closely as possible the text of the published Directory. Page number cross references are correct within this clear print document. Some information may appear in a different place from its location in the published Directory. Complex layouts and graphics have been omitted. It is black and white omn A4 pages for ease of printing. The Agenda and Directory and other conference publications, in PDF, plain text and clear print formats, are available online at www.libdems.org.uk/conference_papers Page 1 Directory Liberal Democrats Autumn Conference 2019 Clearprint Welcome to the Liberal Democrat 2019 conference Directory. If you have any questions whilst at conference please ask a conference steward or go to the Information Desk on the ground floor of the Bournemouth International Centre. Conference venue Bournemouth International Centre (BIC) Exeter Road, Bournemouth, BH2 5BH. Please note that the BIC is within the secure zone and that access is only possible with a valid conference pass. Conference hotel Bournemouth Highcliff Marriott St Michael’s Rd, West Cliff, Bournemouth, BH2 5DU. Further information, registration and conference publications (including plain text and clear print versions) are available at: www.libdems.org.uk/conference For information about the main auditorium sessions, see the separate conference Agenda. DEMAND BETTER THAN BREXIT Page 2 Directory Liberal Democrats Autumn Conference 2019 Clearprint Contents Feature . 4–5 Our time is now by Jo Swinson MP Conference information: . 6–13 Exhibition: . 14–26 List of exhibitors . -

The Blair Government's Proposal to Abolish the Lord Chancellor

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2005 Playing Poohsticks with the British Constitution? The Blair Government's Proposal to Abolish the Lord Chancellor Susanna Frederick Fischer The Catholic University, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susanna Frederick Fischer, Playing Poohsticks with the British Constitution? The Blair Government's Proposal to Abolish the Lord Chancellor, 24 PENN. ST. INT’L L. REV. 257 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Playing Poohsticks with the British Constitution? The Blair Government's Proposal to Abolish the Lord Chancellor Susanna Frederick Fischer* ABSTRACT This paper critically assesses a recent and significant constitutional change to the British judicial system. The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 swept away more than a thousand years of constitutional tradition by significantly reforming the ancient office of Lord Chancellor, which straddled all three branches of government. A stated goal of this legislation was to create more favorable external perceptions of the British constitutional and justice system. But even though the enacted legislation does substantively promote this goal, both by enhancing the separation of powers and implementing new statutory safeguards for * Susanna Frederick Fischer is an Assistant Professor at the Columbus School of Law, The Catholic University of America, in Washington D.C. -

The Inner Workings of British Political Parties the Interaction of Organisational Structures and Their Impact on Political Behaviours

REPORT The Inner Workings of British Political Parties The Interaction of Organisational Structures and their Impact on Political Behaviours Ben Westerman About the Author Ben Westerman is a Research Fellow at the Constitution Society specialising in the internal anthropology of political parties. He also works as an adviser on the implications of Brexit for a number of large organisations and policy makers across sectors. He has previously worked for the Labour Party, on the Remain campaign and in Parliament. He holds degrees from Bristol University and King’s College, London. The Inner Workings of British Political Parties: The Interaction of Organisational Structures and their Impact on Political Behaviours Introduction Since June 2016, British politics has entered isn’t working’,3 ‘Bollocks to Brexit’,4 or ‘New Labour into an unprecedented period of volatility and New Danger’5 to get a sense of the tribalism this fragmentation as the decision to leave the European system has engendered. Moreover, for almost Union has ushered in a fundamental realignment a century, this antiquated system has enforced of the UK’s major political groupings. With the the domination of the Conservative and Labour nation bracing itself for its fourth major electoral Parties. Ninety-five years since Ramsay MacDonald event in five years, it remains to be seen how and to became the first Labour Prime Minister, no other what degree this realignment will take place under party has successfully formed a government the highly specific conditions of a majoritarian (national governments notwithstanding), and every electoral system. The general election of winter government since Attlee’s 1945 administration has 2019 may well come to be seen as a definitive point been formed by either the Conservative or Labour in British political history. -

![Lexis, 7 | 2012, « Euphemism As a Word-Formation Process » [Online], Online Since 25 June 2012, Connection on 23 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0966/lexis-7-2012-%C2%AB-euphemism-as-a-word-formation-process-%C2%BB-online-online-since-25-june-2012-connection-on-23-september-2020-2490966.webp)

Lexis, 7 | 2012, « Euphemism As a Word-Formation Process » [Online], Online Since 25 June 2012, Connection on 23 September 2020

Lexis Journal in English Lexicology 7 | 2012 Euphemism as a Word-Formation Process L'euphémisme comme procédé de création lexicale Keith Allan, Kate Burridge, Eliecer Crespo-Fernández and Denis Jamet (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/334 DOI: 10.4000/lexis.334 ISSN: 1951-6215 Publisher Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Electronic reference Keith Allan, Kate Burridge, Eliecer Crespo-Fernández and Denis Jamet (dir.), Lexis, 7 | 2012, « Euphemism as a Word-Formation Process » [Online], Online since 25 June 2012, connection on 23 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/334 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/lexis. 334 This text was automatically generated on 23 September 2020. Lexis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Denis Jamet Papers X-phemism and creativity Keith Allan The Expressive Creativity of Euphemism and Dysphemism Miguel Casas Gómez Euphemism and Language Change: The Sixth and Seventh Ages Kate Burridge “Frequent fl- erm traveler” – La reformulation euphémistique dans le discours sur l’événement Charlotte Danino Lexical Creation and Euphemism: Regarding the Distinction Denominative or Referential Neology vs. Stylistic or Expressive Neology María Tadea Díaz Hormingo Double whammy! The dysphemistic euphemism implied in unVables such as unmentionables, unprintables, undesirables Chris Smith The Translatability of Euphemism and Dysphemism in Arabic-English Subtitling Mohammad Ahmad Thawabteh The tastes and distastes of verbivores – some observations on X-phemisation in Bulgarian and English Alexandra Bagasheva Lexis, 7 | 2012 2 Introduction Denis Jamet 1 The English word “euphemism” can be traced back for the first time in a book written in 1656 by Thomas Blount, Glossographia [Burchfield 1985: 13], and comes from Greek euphèmismos, which is itself derived from the adjective euphèmos, “of good omen” (from eu, “good”, and phèmi, “I say”). -

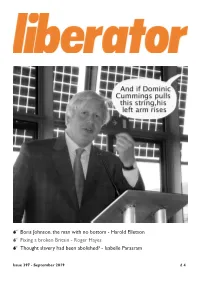

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

Multicultural Broadcasting: Concept and Reality Report Edited by Andrea Millwood Hargrave

Multicultural Broadcasting: concept and reality Report edited by Andrea Millwood Hargrave November 2002 Multicultural Broadcasting: concept and reality Report edited by Andrea Millwood Hargrave Director of the Joint Research Programme Broadcasting Standards Commission and Independent Television Commission British Broadcasting Corporation Broadcasting Standards Commission Independent Television Commission Radio Authority November 2002 Contents 1 Summary 1 1.1 Audience Attitudes 1 1.2 Industry Attitudes 4 2 Background 9 3 Audience Attitudes towards Multicultural Broadcasting 13 3.1 The Place of Mainstream Broadcasting 13 3.2 Specialist Broadcasting Interests: Radio 17 3.3 Levels of Representation in Mainstream Television 20 3.4 Tokenism, Stereotyping and Other Broadcasting Issues 29 3.5 The Future of Multicultural Broadcasting: Audience Views 39 4 Industry Attitudes towards Multicultural Broadcasting 43 4.1 What is Multicultural Broadcasting? 43 4.2 Multicultural Broadcasting Now 51 4.3 The Issue of Programme Genre 61 4.4 Multiculturalism:Guidelines and Policies 68 4.5 Employment and Multiculturalism 74 4.6 The Future of Multicultural Broadcasting: Industry Views 86 5 Advertising and multiculturalism 89 5.1 Audience Attitudes towards Representation in Advertising 89 5.2 TheView from the Advertising Agencies 90 Appendices 1 Minority Ethnic Group Representation on Terrestrial television 97 2. Research Sample and Methodology 109 3. Industry Examples of Multicultural Output 113 4. British Broadcasting Corporation 118 5. Broadcasting Standards Commission 119 6. Independent television Commission 120 7. The radio Authority 121 1 Summary The research examined attitudes towards multicultural broadcasting held by the audience and by practitioners in the radio and television industries. Additionally, attitudes towards multiculturalism within advertising were explored briefly.