The World Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARE & Climate Change

CARE CASE STUDY: Application of Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment (CVCA) Methodology in Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia1 Regional Project for Adaptation to the Impact of Rapid Glacier Retreat in the Tropical Andes – PRAA Two local women from Tapacaya, Bolivia, work together in November 2010 on a participatory exercise as part of CARE’s Climate Vulnerability Capacity Anaylsis (CVCA). 1. Introduction 2. PRAA overview This case study analyzes the results, lessons learned and Andean countries produce 10 percent of the planet’s recommendations emerging from the application of the freshwater, mainly from high Andean ecosystems (páramo) Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment (CVCA) and glaciers. Glacier retreat, however, is increasingly methodology in the context of the PRAA project. First, it limiting this vital water availability. Glaciers located in presents an overview of the project, the areas of intervention the Andean region account for 95 percent of all tropical by country, the results of the analysis itself, and lastly, the glaciers on the globe.2 Yet, the glaciers are retreating at ever main lessons learned and recommendations that arose from increasing rates. It is quite likely that several of them will the application of the tools contained in the CVCA Handbook disappear entirely in the next 15 years, seriously affecting in Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. the availability of water resources for human consumption, agriculture and energy generation. A particular concern The CVCA methodology is a tool developed by CARE to is how the melting of glaciers increases many poor and delineate the socio-economic aspects of vulnerability to vulnerable communities’ risk of and exposure to disasters, climate change, particularly those factors that make women such as landslides, mudslides and lake outbursts, which and other marginalized groups especially vulnerable. -

1 Living with Glaciers, Adapting to Change the Experience of The

Living with glaciers, adapting to change the experience of the Illimani project in Bolivia J. C. Alurralde, E. Ramirez, M. García, P. Pacheco, D. Salazar, R.S. Mamani Proyecto Illimani, UMSA – AGUA SUSTENTABLE, Bolivia Abstract Glaciers retreat’s rate and its impact on rural livelihoods in the tropical Andes were studied and modeled. Tropical glaciers are more affected by climate change than their temperate counterparts due to larger sun exposure and the coincidence of the rainy season with the summer which reduces snow accumulation. Global warming is occurring faster at high altitudes, causing glaciers’ shrinking and affecting downstream communities’ livelihoods where glaciers, important natural water regulators, are the only domestic and productive water source during dry seasons. Changing crop patterns and upward expanding of productive areas are also effects of the climate change. The project studies the Illimani dependent area in a physical and socio-productive context to evaluate its vulnerability to climate change and climate variability, and the already taken autonomous adaptation strategies. Multidisciplinary results are integrated in watershed management models to develop technically and socially validated descriptions of the dynamics between the glacier and the basin, for actual and future scenarios, resulting in proposals for adaptation actions. The findings reveal that climate is not the only triggering factor for autonomous adaptation and the strong heterogeneity of adaptation requirements in mountainous areas even within -

Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey June 2007

Government of Bolivia Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey June 2007 Bolivia Coca Survey for 2006 PREFACE The evidence from the 2006 Bolivia Coca Survey sends mixed signals. Overall, there is an 8% increase in cultivation over 2005 for a total of 27,500 hectares. Dire forecasts have not been borne out. Nevertheless, there are warning signs that should be heeded. Under Bolivian law, 12,000 hectares may be grown for traditional consumption or other legal uses: this Survey shows that the limit was exceeded in the Yungas of La Paz where most of the cultivation usually takes place. At the same time there has been a dramatic (19%) increase in the Chapare region, including more than 2,300 hectares of coca being grown in national parks in the Tropics of Cochabamba – a threat to the precious eco-system of the Amazon forests. The good news from this same region is that the amount of land devoted to the cultivation of alternative crops – such as bananas, pineapple, and palm heart – now exceeds the area used to grow coca. There are signs of hope that licit crops can help liberate vulnerable communities from poverty. Nevertheless, the considerable increase in seizures and the displacement of drug production to areas outside the coca growing areas, as reported by the Bolivian drug control police, demonstrates the need for sustained drug law enforcement of the Bolivian Government. Bolivia’s drug policy is in the spotlight. The Government needs to reassure the world that its support for coca growers will not lead to an increase in cocaine production. -

Ingeniería Sanitaria Y Ambiental REVISTA N°5

Universidad Mayor de San Andrés Ingeniería Sanitaria y Ambiental REVISTA N°5 Agosto 2018 La Paz – Bolivia Edición Principal: Oscar Paz Rada - Instituto de Ingeniería Sanitaria y Ambiental – UMSA Colaboradores en este número: Alison Quiroz Vásquez Carlos España Claudia García Edwin Astorga Sanjinés Esther Sillerico Evelin Susana Humerez Espinoza Froilan Mamani Contenido Gregorio Carvajal Sumi Grover Rivera Ivar Arana Pardo Hernán Coriza Presentación .........................................................................................3 Javier Mendoza Rodriguez Makoto Umeda Prólogo .................................................................................................5 Marilyn Aparicio-Effen Oscar Paz Rada Determinación de la vulnerabilidad sanitaria al cambio climático en relación a la disponibilidad y calidad de agua sobre enfermedades Dirección del IIS: diarreicas en comunidades del municipio de Palca .............................7 Edwin Astorga Modelación de la calidad del agua en el Río Condoriri en los Andes .21 Colaboración especial: Personal técnico - administrativo del IIS Aplicación del método PAJ en la elección de tecnologías de tratamien- to de aguas residuales en Bolivia ......................................................33 Referencias: Al citar este documento debe señalar Herramienta para el diseño sistematizado de la Filtración en Múltiple como: Revista de Ingeniería Sanitaria y Etapa (FiME) ......................................................................................47 Ambiental, UMSA, Facultad de -

Ppcr Bolivia Indice

ESTADO PLURINACIONAL DE BOLIVIA IV Foro – Taller: “resiliencia y adapTación al cambio climáTico” INFORME DE EVALUACIÓN DE INDICADORES CIF Programa Piloto de Resiliencia Climática La Paz – Bolivia Julio 2018 PPCR BOLIVIA INDICE 1. RESUMEN EJECUTIVO .................................................................................................................4 2. ANTECEDENTES ..........................................................................................................................5 3. DESARROLLO DEL IV FORO – TALLER ...........................................................................................8 4. METODOLOGÍA Y SU PROCEDIMIENTO ..................................................................................... 11 Procedimiento Metodológico ....................................................................................................... 12 5. RESULTADOS DE LOS CINCO INDICADORES EN FORMATO CIF ..................................................... 16 6. EVALUACIÓN DEL EVENTO Y LOS AVANCES POR INDICADOR ...................................................... 57 6.1 Evaluación del Indicador 1 ................................................................................................. 57 a) Nivel Nacional ................................................................................................................... 59 b) Sector Riego ...................................................................................................................... 59 c) Sector Recursos Hídricos ................................................................................................... -

4.4 Charana Achiri Santiago De Llallagua Is. Taquiri General Gonzales 3.0 3.1 2.9

N ULLA ULLA TAYPI CUNUMA CAMSAYA CALAYA KAPNA OPINUAYA CURVA LAGUNILLA GRAL. J.J. PEREZ CHULLINA STA. ROSA DE CAATA CHARI GRAL. RAMON CARIJANA GONZALES 2.0 CAMATA AMARETEGENERAL GONZALES MAPIRI VILLA ROSARIO DE WILACALA PUSILLANI CONSATA MARIAPU INICUA BAJO MOCOMOCO AUCAPATA SARAMPIUNI TUILUNI AYATA HUMANATA PAJONAL CHUMA VILAQUE ITALAQUE SUAPI DE ALTO BENI SAN JUAN DE CANCANI LIQUISANI COLLABAMBA GUANAY COTAPAMPA TEOPONTE PUERTO ACOSTA CHINAÑA 6 SANTA ROSA DE AGOSTO ANANEA CARGUARANI PAUCARES CHAJLAYA BELEN SANTA ANA DEL TAJANI PTO. ESCOMA 130 PANIAGUA ALTO BENI PARAJACHI ANBANA TACACOMA YANI QUIABAYA TIPUANI COLLASUYO PALOS BLANCOS V. PUNI SANTA ROSA DE CHALLANA SAN MIGUEL CALLAPATA CALAMA EDUARDO AVAROA DE YARICOA TIMUSI OBISPO BOSQUE SOCOCONI VILLA ELEVACION PTO. CARABUCO CARRASCO LA RESERVA CHUCHULAYA ANKOMA SAPUCUNI ALTO ILLIMANI ROSARIO 112 SORATA CARRASCO ENTRE RIOS PTO. COMBAYA 115 CHAGUAYA ILABAYA ALCOCHE SAN PABLO SOREJAYA SANTA FE CHIÑAJA CARANAVI VILLA MACA MACA CHEJE MILLIPAYA ANCORAIMES SANTA ANA DE CARANAVI PAMPA UYUNENSE CAJIATA FRANZ TAMAYO PTO.RICO SOTALAYA TAYPIPLAYA WARISATA CHOJÑA COTAPATA SAN JUAN DE CHALLANA INCAHUARA DE CKULLO CUCHU ACHACACHI SAN JOSE V. SAN JUAN DE EL CHORO SANTIAGO AJLLATA V. ASUNCION DE CHACHACOMANI ZAMPAYA CORPAPUTO KALAQUE DE HUATA GRANDE CHARIA JANCKO AMAYA CHUA HUARINA MURURATA LA ASUNTA COPACABANA COCANI KERANI TITO YUPANKI CHUA SONCACHI CALATA VILASAYA HUATAJATA LOKHA DE S. M. SAN PABLO PEÑAS VILLA ASUNCION HUAYABAL DE T. COPANCARA TURGQUIA ZONGO KARHUISA COROICO CALISAYA CHAMACA V. AMACIRI2.9 PACOLLO SANTIAGO DE IS. TAQUIRI YANAMAYU SURIQUI HUANCANE OJJE PTO. ARAPATA COLOPAMPA GRANDE PEREZ VILLA BARRIENTOS LA CALZADA CASCACHI HUAYNA POTOSI LAS BATALLAS MERCEDES CORIPATA V. -

Bolivia 2015 Human Rights Report

BOLIVIA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bolivia is a constitutional, multiparty republic with an elected president and a bicameral legislature. On October 12, 2014, in a process deemed free but whose fairness was questioned by international observers, citizens re-elected President Evo Morales Ayma, leader of the Movement Toward Socialism Party (MAS), for a third term. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. The most serious human rights problems included widespread corruption and inefficiency in the country’s law enforcement and judicial system, leading to arbitrary arrest or detention, denial of a fair and timely public trial, and harsh prison conditions. Government officials actively promoted restrictions on freedom of press and association and used legal mechanisms to limit political opposition. Additional human rights problems included abuse by police and military officials, lack of government transparency, violence against women, trafficking in persons, vigilante justice, poor labor conditions, and child labor. Societal discrimination continued against women; members of racial and ethnic minority groups; individuals with disabilities; indigenous persons; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons; and those with HIV/AIDS. Although the government took steps in some cases to prosecute security service and other government officials who committed abuses, inconsistent application of the laws and a dysfunctional judiciary led to impunity. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life While there were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings, several cases of arbitrary or unlawful deprivation of life remained unresolved. -

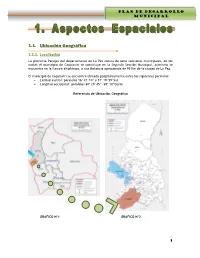

1.1. Ubicación Geográfica

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI 1.1. Ubicación Geográfica 1.1.1. Localización La provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz consta de ocho secciones municipales, de los cuales el municipio de Caquiaviri se constituye en la Segunda Sección Municipal, asimismo se encuentra en la llanura altiplánica, a una distancia aproximada de 95 Km de la ciudad de La Paz. El municipio de Caquiaviri se encuentra ubicado geográficamente entre los siguientes paralelos: Latitud austral: paralelos 16º 47´10” y 17º 19´59”Sur Longitud occidental: paralelos 68º 29´45”- 69º 10”Oeste Referencia de Ubicación Geográfica GRAFICO Nº1 GRAFICO Nº2 1 PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI Ubicación del Municipio Caquiaviri en la Provincia Pacajes GRAFICO Nº3 1.1.2. Límites Territoriales El municipio de Caquiaviri tiene la siguiente delimitación: Límite Norte; Municipios de Jesús de Machaca y San Andrés de Machaca de la provincia Ingavi y el Municipio Nazacara de Pacajes que es la Séptima Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Sur; Municipios Coro Coro, Calacoto y Charaña que son Primera, Tercera y Quinta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Este; Municipio Comanche que es Cuarta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Oeste; Municipio de Santiago de Machaca de la provincia José Manuel Pando del departamento de La Paz. 1.1.3. Extensión La Provincia Pacajes posee una extensión total de 10.584 km², de la cual la Segunda Sección Municipal Caquiaviri representa el 14 % del total de la provincia, lo que equivale a una superficie de 1.478 Km². -

Distribution, Diversity and Conservation Status of Bolivian Amphibians

Distribution, diversity and conservation status of Bolivian Amphibians Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrichs-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Steffen Reichle aus Stuttgart Bonn, 2006 Diese Arbeit wurde angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch- Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn. 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. W. Böhme 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. G. Kneitz Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 27. Februar 2007 "Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni- bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert" Erscheinungsjahr: 2007 CONTENTS Acknowledgements I Introduction 1. Bolivian Amphibians 1 2. Conservation problems of Neotropical Amphibians 2 3. Study area 3 3.1 Bolivia – general data 3 3.2 Ecoregions 4 3.3 Political and legal framework 6 3.3.1 Protected Areas 6 II Methodology 1. Collection data and collection localities 11 2. Fieldwork 12 2.1 Preparation of voucher specimens 13 3. Bioacustics 13 3.1 Recording in the field 13 3.2 Digitalization of calls, analysis and visual presentation 13 3.3 Call descriptions 13 4. Species distribution modeling – BIOM software 14 4.1 Potential species distribution 14 4.2 Diversity pattern and endemism richness 14 5. Assessment of the conservation status 14 5.1 Distribution 15 5.2 Taxonomic stability 15 5.3 Presence in Protected Area (PA) 15 5.4 Habitat condition and habitat conversion 16 5.5 Human use of the species 16 5.6 Altitudinal distribution and taxonomic group 16 5.7 Breeding in captivity 17 5.8 Conservation status index and IUCN classification 17 III Results 1. -

Plan De Desarrollo Municipal

GOBIERNO MUNICIPAL DE CHULUMANI “VILLA DE LA LIBERTAD” PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL 2006 –2010 Gobierno Municipal de Chulumani “Villa de la Libertad” Primera Sección de la Provincia Sud Yungas PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL GOBIERNO MUNICIPAL DE CHULUMANI “VILLA DE LA LIBERTAD” CONTENIDO A. ASPECTOS ESPACIALES 1 A. 1. Ubicación Geográfica 1 a.1. 1. Latitud y longitud 1 a.1.2. Limites Territoriales 1 a.1.3. Extensión 2 a.2.1. Distritos y comunidades 2 a.2.2. Centros poblados 3 A.3. Manejo espacial. 4 a.3.1. Uso y ocupación del espacio. 4 B. ASPECTOS – FISIOGRÁFICOS 5 B.1. Descripción Fisiográfica 5 b.1.1. Altitud 5 b.1.2. Relieve y Topografía 5 B.2. Características físico-biológicas 6 b.2.1. Pisos ecológicos 6 b.2.1.1. Clima 7 b.2.1.1.1. Temperatura promedio, máxima y mínima 7 b.2.1.1.2. Precipitaciones pluviales 8 b.2.1.1.3. Humedad relativa 8 b.2.1.1.4. Evaporación. 9 b.2.1.1.5. Heliofania 9 b.2.1.1.6. Evapotranspiración 9 b.2.1.1.7. Riesgos climáticos 9 b.2.1.2. Suelos 10 b.2.1.2.1. Principales características 10 b.2.1.2.2. Zonas y grados de erosión 11 b.2.1.2.3. Prácticas y superficies recuperadas 12 b.2.1.3. Flora y recursos forestales 12 b.2.1.3.1. Principales especies 12 b.2.1.3.2. Plantas medicinales 15 b.2.1.4. Fauna, insectos y enfermedades de las plantas. -

Phd Thesis Philipp Horn.Pdf

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Indigeneity, Constitutional Changes and Urban Policies: Conflicting Realities in La Paz, Bolivia and Quito, Ecuador Thesis How to cite: Horn, Philipp (2015). Indigeneity, Constitutional Changes and Urban Policies: Conflicting Realities in La Paz, Bolivia and Quito, Ecuador. PhD thesis The University of Manchester. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2015 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.686747 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk INDIGENEITY, CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGES AND URBAN POLICIES: CONFLICTING REALITIES IN LA PAZ, BOLIVIA AND QUITO, ECUADOR A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 PHILIPP HORN School of Environment, Education and Development Table of contents List of tables ......................................................................................................................... 5 List of figures ....................................................................................................................... 6 List of boxes ........................................................................................................................ -

Assessment of Prospects for Flood Hazard Mitigation in the La Paz River Watershed Area

ASSESSMENT OF PROSPECTS FOR FLOOD HAZARD MITIGATION IN THE LA PAZ RIVER WATERSHED AREA PROJECT EXECUTED BY CARE BOLIVIA – USAID 2002 ASSESSMENT OF PROSPECTS FOR FLOOD HAZARD MITIGATION IN THE LA PAZ RIVER WATERSHED AREA TABLE OF CONTENTS ASSESSMENT OF PROSPECTS FOR FLOOD HAZARD MITIGATION IN THE LA PAZ RIVER WATERSHED AREA ............................................................................................................................... 1 ASSESSMENT OF PROSPECTS FOR FLOOD HAZARD MITIGATION IN THE LA PAZ RIVER WATERSHED AREA ............................................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 8 1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 14 1.1 GEOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................... 15 1.1.1 The High plateau (Altiplano), ............................................................................................ 15 1.1.2 The Sub Andean Zone, ...................................................................................................