News Media and the Changes in Disaster Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ofcom Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21

The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 HC 459 The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraphs 11 and 12 of Schedule 1 of the Office of Communications Act 2002 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 8 July 2021. Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers Laid before the Welsh Parliament by the Rt Hon Mark Drakeford MS, the First Minister of Wales HC 459 © Ofcom Copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2705-4 CCS0521569280 07/21 SG/2021/123 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by Hobbs the Printers on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Chair’s Message 4 Chief Executive’s Report 6 Section A: Performance Report 8 Overview 9 Performance Review 11 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 43 Stakeholder Engagement 47 Financial Review 55 Corporate Responsibility 61 Sustainability Report 64 Section B: Accountability Report 66 Governance 67 Our Employees 92 Remuneration Report 96 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller 103 and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament Section C: Financial Statements 106 Statement of Income and Expenditure 107 Statement of Comprehensive Net Expenditure 107 Statement of Financial Position 108 Statement of Changes in Equity 109 Statement of Cash Flows 110 Notes to the Accounts 111 Section D: Annexes 148 A1. -

Spring 2006 Bulletin 85

Advertisements Diary Dates Please refer to VLV when responding to advertisements. VLV Ltd cannot accept any liability or complaint in regard to the following offers. The charge for classified advertisements is 30p per word, 20p for Wednesday 26 April members. Please send typed copy with a cheque made payable to VLV Ltd. For display space please VLV Spring Conference contact Linda Forbes on 01474 352835. The Royal Society, London SW1 10.30am – 5.00pm The Radio Listener's Guide 2006 The Television Viewer's Guide 2006 Wednesday 26 April Presentation of VLV’s Awards G 160 pages G 160 pages for Excellence In Broadcasting G Frequencies for all BBC and commercial radio G Digital TV details of what you need to pick up Sky, The Royal Society, London SW1 stations, plus DAB digital transmitter details. Freeview or cable 1.45pm – 2.30pm G Radio Reviews Independent reviews of over G Transmitter sites for all analogue and digital Thursday, 11 May 130 radios including DAB digital radios. television transmitters. An Evening with Joan Bakewell G News from both BBC and commercial radio stations. G Equipment advice covering TV sets, VCRs, DVD One Whitehall Place, players and recorders, Sky and Freeview. G Digital Radio (DAB) The latest news and information. London SW1 G Freeview set-top box guide. 6.30pm – 8.20pm G Sky and Freeview radio information and G channel lists. Channel lists for Sky and Thursday, 18 May Freeview. VLV Evening Seminar with Mark G Advice showing how to get the G Thompson, BBC Director General best from your radio. -

The Future of Public Service Broadcasting

House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The future of public service broadcasting Sixth Report of Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the Report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 17 March 2021 HC 156 Published on 25 March 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Julian Knight MP (Conservative, Solihull) (Chair) Kevin Brennan MP (Labour, Cardiff West) Steve Brine MP (Conservative, Winchester) Alex Davies-Jones MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Julie Elliott MP (Labour, Sunderland Central) Rt Hon Damian Green MP (Conservative, Ashford) Rt Hon Damian Hinds MP (Conservative, East Hampshire) John Nicolson MP (Scottish National Party, Ochil and South Perthshire) Giles Watling MP (Conservative, Clacton) Heather Wheeler MP (Conservative, South Derbyshire) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/. Committee Reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/dcmscom and in print by Order of the House. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

Stijdenincorporating Jail R Magazine � Britain's Biggest Weekly Student Newspaper April 26, 1996

26 APR 1!:":i'j They think it's all over HOW DID MIR TEAM WORE OVER THE EASIER VOW CUISSIFIED RESULTS SERVICE: TOTAL FOOTSAEL. PAGE 17 STIJDENIncorporating jail r magazine Britain's biggest weekly student newspaper April 26, 1996 THEY TREATED ME LIKE A TERRORIST' SAYS JAILED STUDENT Thrown in solitary for losing passport B MARTIN ARNOLD. CHIEF REPORTER A SPANISH field trip turned into a r nightmare for student Mark Vinton when RADIO DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN airport police refused him entry and threw him in solitary confinement. Heavy-handed officials bundled Mark into a cell because he could not produce his passport - it had been lost in the post. Yet hours before the trip Mark had received a special fax from Spanish immigration officials authorising his entry to the country. Airport police dismissed it and locked Mark away, while tutors pleaded in vain for his release, Mark was stopped as he arrived with a group of 60 other Leeds University students and four lecturers. -They thought I was a terrorist.," said Mark. tried to reason v.ith them but they juvi wouldn't listen." Astonished Spanish police detained the astonished student in solitary confinement for more than seven hours as they sought to deport him back to Britain. It was only after an intervention by the Home Office that he was filially released and allowed to rejoin the Leeds $roup. University staff who attempted to intervene through their travel agent had been told nobody would be allowed to speak to Mark as he ramd immediate di:potation. -

Public Service Broadcasting: As Vital As Ever

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Communications and Digital 1st Report of Session 2019 Public service broadcasting: as vital as ever Ordered to be printed 31 October 2019 and published 5 November 2019 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 16 Select Committee on Communications and Digital The Select Committee on Communications and Digital is appointed by the House of Lords in each session “to consider the media, digital and the creative industries”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on Communications and Digital are: Lord Allen of Kensington Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall Baroness Bull Baroness Meyer Viscount Colville of Culross Baroness Quin Lord Gilbert of Panteg (Chairman) Baroness Scott of Bybrook Lord Gordon of Strathblane Lord Storey Baroness Grender The Lord Bishop of Worcester Lord McInnes of Kilwinning Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords- interests Publications All publications of the Committee are available at: http://www.parliament.uk/hlcommunications Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at: http://www.parliamentlive.tv Further information Further information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is available at: http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords Committee staff The staff who worked on this inquiry were Theodore Pembroke (Clerk), Theo Demolder (Policy Analyst) and Rita Cohen (Committee Assistant). Contact details All correspondence should be addressed to the Select Committee on Communications and Digital, Committee Office, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW. -

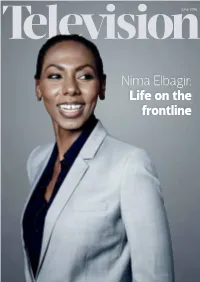

Nima Elbagir: Life on the Frontline Size Matters a Provocative Look at Short-Form Content

June 2016 Nima Elbagir: Life on the frontline Size matters A provocative look at short-form content Pat Younge CEO, Sugar Films (Chair) Randel Bryan Director of Content and Strategy UK, Endemol Shine Beyond UK Adam Gee Commissioning Editor, Multi-platform and Online Video (Factual), Channel 4 Max Gogarty Daily Content Editor, BBC Three Kelly Sweeney Director of Production/Studios, Maker Studios International Andy Taylor CEO, Little Dot Studios Steve Wheen CEO, The Distillery 4 July The Hospital Club, 24 Endell Street, London WC2H 9HQ Booking: www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society June 2016 l Volume 53/6 From the CEO The third annual RTS/ surroundings of the Oran Mor audito- Mockridge, CEO of Virgin Media; Cathy IET Joint Public Lec- rium in Glasgow. Congratulations to Newman, Presenter of Channel 4 News; ture, held in the all the winners. and Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom. unmatched surround- Back in London, RTS Futures held Steve Burke, CEO of NBCUniversal, ings of London’s Brit- an intimate workshop in the board- will deliver the opening keynote. ish Museum, was a room here at Dorset Rise: 14 industry An early-bird rate is available for night to remember. I newbies were treated to tips on how those of you who book a place before was thrilled to see such a big turnout. to secure work in the TV sector. June 30 – just go to the RTS website: Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse gave a Bookings are now open for the RTS’s rts.org.uk/event/rts-london-conference-2016. -

24 September 2019)

Project no: Advisory Committee for Wales Author: Lloyd Watkins Minutes of the 74th ACW Meeting (24 September 2019) For information Document no: ACW74 Project director: Eleanor Marks Submitted to: ACW 75 (3) Project manager: Elinor Williams Submitted by: Lloyd Watkins Date written: 24 October 2019 Project sponsor: Elinor Williams 1. Input requested To approve the minutes of the 74th meeting of the Advisory Committee for Wales held on 24 September 2019. 2. Summary of analysis PRESENT: Committee: Hywel Wiliam (Chairman) (HW) Robert Andrews (RA) Peter Trott (Member) (PT) Ruth McElroy (RM) Aled Eirug (Content Board Member for Wales) (AE) Karen Lewis (Communications Consumer Member for Wales) (KL) David Jones (Ofcom Board Member for Wales) (DJ) Ofcom Staff: Elinor Williams, Principal, Regulatory Affairs Wales (EW) Joanna Davies, Senior Welsh Language Advisor (JD) Lloyd Watkins, Regulatory Affairs Advisor (LW) London Emma McFadyen, Government & Parliament Nations representative (EMcF) Katie Pettifer, Director, Government & Parliament Director (KP) Anthony Szynkaruk, Principal, Content Policy (AS) Garreth Lodge, Associate, Content Policy Advisor (GL) Gary Clemo, Principal, Technology Advisor (GC) Tom Lancaster, Associate, Content Policy (TL) Tom Walker, Principal, Content Policy (TW) Alex Waterfield, Senior Associate, Content Policy (AW) Vikki Cook, Director, Content Media Policy (VC) Guy Holcroft, Head of Audience Management, Market Intelligence (GH) Katerina Sklavounou, Senior Associate, Strategy & Policy (KS) Amy Luong, Graduate, Business Planning and Reporting Corporate Services Group (AL) 1 Item 1: Chairman’s Introduction & Apologies for Absence 1. The Chairman, Hywel Wiliam (HW), welcomed Members and Ofcom Wales staff to the 74th meeting of the Ofcom Advisory Committee for Wales (ACW) held at M-Sparc, Anglesey, North Wales. -

Cteerc/S5/17/29/A Culture, Tourism, Europe And

CTEERC/S5/17/29/A CULTURE, TOURISM, EUROPE AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE AGENDA 29th Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Thursday 14 December 2017 The Committee will meet at 10.00 am in the David Livingstone Room (CR6). 1. Decision on taking business in private: The Committee will decide whether to take item 3 in private. 2. Ofcom and broadcasting: The Committee will take evidence from— Glenn Preston, Director Scotland, and Kevin Bakhurst, Group Director, Content and Media Policy, Ofcom. 3. Ofcom and broadcasting: The Committee will consider the evidence heard earlier in the meeting: Katy Orr Clerk to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee Room Tower T3.40 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5234 Email: [email protected] The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda item 2 Note by SPICe CTEERC/S5/17/29/1 PRIVATE PAPER CTEERC/S5/17/29/2 (P) CTEERC/S5/17/29/1 Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee 29th Meeting, 2017 (Session 5) Thursday 14 December Ofcom and Broadcasting This paper included— Background on witnesses Background briefing Lines of questioning (at the end of the paper) Witnesses Glenn Preston, Director, Scotland Glenn Preston heads the Nations team in Scotland in addition to leading the development of Ofcom’s expanding Edinburgh office as part of its “Out of London strategy”. Ofcom’s presence in Scotland will grow to around 40 people with representation from across the organisation. Glenn Preston joined Ofcom in October 2016 after having spent 17 years in the Civil Service, latterly as Policy Deputy Director at the Scotland Office. -

Cbbc Roadshows 2002

CBBC ROADSHOWS 2002 Mon 29th July Beach, Skegness, England (Foreshore) With Darius, S Club Juniors, and ATC Wed 31st July Wythenshawe Park, Manchester, England With Blue, 3SL, and Boniface Mon 5th August Beach, Blackpool, England (next to central pier) With Abs, Liberty X, Busted and Omero Wed 7th August Events Arena, Rhyl Promenade, Rhyl With Sugababes, 3SL and Hear’Say Mon 12th August Castlewellan Forest Park, Castlewellan, Northern Ireland With H & Claire, Six and Harvey (So Solid Crew) Wed 14th August Irvine Beach Park, Irvine, Scotland With a1 and D Mac Mon 19th August The Hoe, Plymouth, England With Atomic Kitten Wed 21st August Barrowfields, Newquay, England With Liberty X Hold on tight - CBBC are gearing up for their biggest summer ever and are coming to a town near you! Following the massive success of the Blue Peter roadshows last year, CBBC have decided to make this summer even bigger and better by staging eight UK roadshows, hosted by the stars of favourites Blue Peter, Xchange and CBBC. All eight live shows will bring the very best of CBBC to towns around the UK - a mix of top pop guests - your favourite CBBC stars - and some amazing competitions and giveaways. CBBC is also on the look-out for the hot new dancing talent of the future and will be staging a top competition where you could be spotted by Popstars talent guru Nicki Chapman. At each roadshow, CBBC will be holding a dance competition, the winners from each show going through to the grand final at the last roadshow. The lucky overall winners will get coaching from a team of choreographers, and the chance to perform with Gareth Gates on Blue Peter later on this year. -

Ofcom Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20

Our mission is to make communications work for everyone. The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts HC 644 For the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020 This document is also available in Welsh: Adroddiad a Chyfrifon Blynyddol y Swyddfa Gyfathrebiadau 1 The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraphs 11 and 12 of Schedule 1 of the Office of Communications Act 2002 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 21 July 2020. Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers Laid before the Welsh Parliament by the Rt Hon Mark Drakeford MS, the First Minister of Wales HC 644 2 Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20 © Ofcom Copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2043-7 CCS0320313510-001 SG/2020/106 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Hobbs the Printers on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 3 Contents Chair’s message 4 Chief Executive’s report 6 A Performance Report 1. -

Blue Peter Celebrates 5,000 Episodes Pension Page 2 Scheme | Back at the Bbc

The newspaper for retired BBC Pension Scheme members • April 2018 • Issue 2 PROSPERO BLUE PETER CELEBRATES 5,000 EPISODES PENSION PAGE 2 SCHEME | BACK AT THE BBC WHEN FRED BECAME FREDA... by Matt Eastley Blue Peter celebrated its 5,000th edition on 31 January. Ariel Editor, Matt Eastley recalls a reptilian mystery and pays tribute to a programme that, for most of us, holds a special place in our hearts. loved my school days but Blue Peter sparked possibly the most useless educational exercise ever, prompted Iby the sex of a lazy and unenterprising tortoise. The tortoise in question was called Fred and was one of a long line of pets to have graced the programme down the years. Fred was a spectacularly dull reptile, who never did anything. My older sister used to tell me: ‘You’re more boring than Fred,’ if she wanted to annoy me, which she did, frequently. While other Blue Peter pets such as the dogs Patch, Petra, Shep, Goldie or Honey seemed to have a vestige of personality, Fred was a crashing bore. His party piece was falling asleep mid programme. He was desperately uninteresting. Yet this lethargic creature found itself at the centre of a mini scandal when an eagle-eyed viewer spotted – and to this day I don’t know how – that Fred was Blue Peter presenters with the real stars: Meg (collie), Mabel (mongrel), Lucy (retriever) and Smudge (kitten). actually… female. The animal John Noakes was quickly renamed Freda. the annual Blue Peter appeal, which didn’t ask for money with Freda.