Public Service Broadcasting: As Vital As Ever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intergenerational Solidarity and the Needs of Future Generations

United Nations A/68/x.. General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2013 Original: English Word count (including footnotes/endnotes): 8419 Sixty-eighth session Item 19 of the provisional agenda Sustainable Development: Intergenerational solidarity and the needs of future generations Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report is prepared pursuant to paragraph 86 of the Rio+20 outcome document, which requests the Secretary-General to provide a report on the need for promoting intergenerational solidarity for the achievement of sustainable development, taking into account the needs of future generations. The report evaluates how the need for intergenerational solidarity could be addressed by the United Nations system and analyses how the issue of intergenerational solidarity is embedded in the concept of sustainable development and existing treaties, and declarations, resolutions, and intergovernmental decisions. It also reviews the conceptual A/68/100 A/68/x.. and ethical underpinnings of intergenerational solidarity and future generations and how the issue has been taken into consideration in policy-making at the national level in a variety of institutions. The report outlines options for possible models to institutionalize concern for future generations at the United Nations level, as well as suggesting options for the way forward. 2 A/68/x.. Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction………………………………………… II. Conceptual framework (a) Conceptual and ethical dimensions (b) Economics III. Existing arrangements and lessons learnt (a) Needs of future generations in international legal instruments (b) Legal provisions at the national level (c) National institutions for future generations (d) Children and youth (e) Proposals related to a High Commissioner for Future Generations IV. -

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

PSB Report Definitions

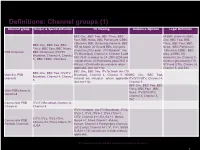

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Ofcom Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21

The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 HC 459 The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraphs 11 and 12 of Schedule 1 of the Office of Communications Act 2002 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 8 July 2021. Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers Laid before the Welsh Parliament by the Rt Hon Mark Drakeford MS, the First Minister of Wales HC 459 © Ofcom Copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2705-4 CCS0521569280 07/21 SG/2021/123 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by Hobbs the Printers on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Chair’s Message 4 Chief Executive’s Report 6 Section A: Performance Report 8 Overview 9 Performance Review 11 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 43 Stakeholder Engagement 47 Financial Review 55 Corporate Responsibility 61 Sustainability Report 64 Section B: Accountability Report 66 Governance 67 Our Employees 92 Remuneration Report 96 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller 103 and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament Section C: Financial Statements 106 Statement of Income and Expenditure 107 Statement of Comprehensive Net Expenditure 107 Statement of Financial Position 108 Statement of Changes in Equity 109 Statement of Cash Flows 110 Notes to the Accounts 111 Section D: Annexes 148 A1. -

Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations

Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations Science and Environmental Health Network The International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations Science and Environmental Health Network The International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School October 2008 http://www.sehn.org http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/hrp The Science & Environmental Health Network (“SEHN”) engages communities and governments in the effective application of science to restore and protect public and ecosystem health. SEHN is a leading proponent of the precautionary principle as a basis for public policy. Our goal is policy reform that promotes just and sustainable communities, for this and future generations. The International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) at Harvard Law School is a center for critical thought and active engagement in human rights. The IHRC provides students the opportunity to engage directly with the vital issues, insti- tutions and processes of the human rights movement. Each year, the IHRC part- ners with dozens of local and international non-governmental organizations to work on human rights projects ranging from litigation, on-site investigations, legal and policy analysis, report drafting for international oversight bodies, and the development of advocacy strategies. MODELS FOR PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS Table of Contents I. Summary 1 II. Legal Bases for Present Promotion of Future Interests 3 A. The Interests of Future Generations 4 B. Duties to and Rights of Future Generations 6 C. Guardians and Trustees for Future Generations 9 III. Legal Mechanisms and Institutions for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations 11 A. -

African Cats Study Notes

African Cats Directed by: Keith Scholey and Alastair Fothergill Certificate: U (contains documentary footage of animals hunting and fighting) Running time: 89 mins Release Date: 27th April 2012 Suitable for: The activities in these study notes address aspects of the curriculum for literacy, science and geography for pupils between ages 5–11. www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites Synopsis An epic true story set against the backdrop of one of the wildest places on Earth, African Cats captures the real-life love, humour and determination of the majestic kings of the Savannah. The story features Mara, an endearing lion cub who strives to grow up with her mother’s strength, spirit and wisdom; Sita, a fearless cheetah and single mother of five mischievous newborns; and Fang, a proud leader of the pride who must defend his family from a rival lion and his sons. Genre African Cats is a nature documentary, referred to by its producers as a ‘true life adventure’. It was filmed in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, a major game region in southwestern Kenya. The film uses real-life footage to tell the true story of two families of wild animals, both fighting to survive in the Savannah. African Cats features a voiceover narration by the actor Samuel L. Jackson and a portion of the money made from ticket sales went to the African Wildlife Foundation. Before SeeinG the film Review pupils’ understanding of the documentary genre. How are they different to other films they watch? Make two lists, one of nature documentaries children have seen (e.g. -

Tennessee, Chamber of Commerce Page 1 of 8 4

D . Lake City, Tennessee, Chamber of Commerce Page 1 of 8 4 Business Directory Select the classification of the business you- desire. IBanks & Financial Sewices 4%- Banks I Financial Services Member Name I Address I City \Statel Zip I Phone BankAmerica 1P.O. Box614 ]Lake Citv. ITN 1377691 426-7481 SunTrust Bank IP.0. Box 68 ILake City ITN 1377691 426-7451 First Choice Financial I I I I I Group 2841 Norris Freeway Andemnville TN 37705 494-0702 First National Bank 2106 N Charles Seivers Blvd. Clinton TN 37716 457-8684 423-562- Peoples National Bank P.O. Box 1221 LaFolletle TN 37766 4921 . ~-Return to Top of .me Chambers of Commerce Member Name I Address I Ci lStatel Zia I Phone 1 ~ ~~ -~ Anderson County Chamber of Commerce 245 N. Main St., Suite 200 Clinton TN 37716 457-2559 Knoxville Chamber 601 W. Summit Hill Dr., Suite Partnership 300 Knoxville TN 37902 637-4550 Monroe County Chamber 423-442- of Commerce 4765 Highway 68 Madisonville TN 37354 4588 http://~.lak~i~.or~directory.html 711 6/03 . Lake City, Tennessee, Chamber of Commerce Page 2 of 8 Member Name Address City State Zip Phone Lake City Chnstian Fellowship 506 4th Street, POB 939 LakeCity TN 37769 426-6544 Ret-umto1op-dPme Communications Yellow Book Southern Returnto Top of Page Healthcare I http Nwww lakecitytn.org/directory html 71 16/03 . Lake City, Tennessee, Chamber of Commerce Page 3 of 8 Noe, Dr. Ronald E IP.0. Box 599 ILake City ITN 1377691 426-7421 Pryse, Dr. John C., Jr I180 Edgewood Ave. -

Regulating the National Lottery

Section 5 Regulating the National Lottery The Third National Lottery Licence May 2021 The Third Licence Conditions 1. Grant of Licence 2. Definitions and Interpretation 3. Commencement 4. Handover from the Previous Licence 5. Service requirement 6. Prohibition of activities not related to the National Lottery 7. Consumer Protection 8. Retailer commission and retailer management 9. Independent section 6 licence applicants 10. Information and reporting 11. Payments to the Secretary of State 11A. Promotion of the National Lottery 12. Shareholders, other Connected parties and debt providers 13. Vetting 14. Control environment 15. Contractors 16. Employees 17. Performance monitoring 18. Handover on expiry or revocation of the Licence 19. Security for Players’ funds 20. Confidentiality and freedom of information 21. Intellectual Property 22. Data Protection 23. Licence extensions 24. No waiver 25. Severability 26. Governing Law and jurisdiction 27. Third Party rights 28. Notices 29. Survival Schedules Schedule 1 Definitions Schedule 2 Part 1 Games and facilities to be available in the first five weeks of the Licence Schedule 2 Part 2 Financial penalties Schedule 2 Part 3 Schedule 3 Handover from the Previous Licensee Schedule 4 Part 1 Ancillary activities that the Commission has consented to Schedule 4 Part 2 Further Conditions relating to Ancillary Activities Schedule 5 The Ancillary Activity Payment Schedule 6 Schedule 7 Codes of practice and strategies Schedule 8 Primary and Secondary Contributions Part 1 Definitions and interpretation Schedule -

BBC Learning – Commissioning Meeting

BBC Learning – Commissioning Meeting May 2012 Welcome and Introduction Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning BBC North • BBC Learning is now located at MediaCityUK, Salford • The move to Salford aims to ensure we better serve and reflect Northern audiences • Other departments based here include: o Sport o Children’s o 5 live o Future Media o BBC Breakfast Welcome and Introduction • Our fourth session to share plans and future thinking • This is the second of two sessions held today: o AM – aimed at education publishers and distributors o PM – commissioning meeting for BBC suppliers • Minutes and recordings of both events will be put online Welcome and Introduction At the last meeting in October 2011 we covered: o Update on Learning activity and content o Information on BBC Learning online activity and plans o Emerging thoughts on the Knowledge and Learning Product o Information on BBC Learning television and Learning Zone plans o Update on finance and public affairs activity Agenda model Timing Agenda Item Speaker 2.30pm Introduction and Welcome Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning Learning and Strategy Update The Knowledge and Learning Product Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning Chris Sizemore – Executive Editor, BBC Learning BBC Learning Online Commissioning Chris Sizemore – Executive Editor, BBC Learning BBC Learning Television Abigail Appleton – Head of Commissioning, BBC Learning BBC Two: The Learning Zone Katy Jones – Executive Producer, BBC Learning Finance and Industry Engagement Alex Lloyd – Head of Operations and Public Affairs, -

Bbc Global Audience Measure

BBC GLOBAL AUDIENCE MEASURE A quick guide What exactly is the Global Audience Measure (GAM)? The Global Audience Measure is an annual update of how many people are consuming the BBC weekly for ALL international services excluding the BBC’s output aimed at the UK market in ALL countries across ALL platforms (TV, Radio, website and social media). The GAM builds 240 ‘single customer view’ models, one for every country in the world, each year. We do this by combining measurement data for BBC radio, TV, websites and social media: TV and radio data counts people through either surveys that we run in market, or through ratings data (BARB in the UK, or Arbitron in the USA, generally industry currencies in key developed markets). As surveys are extremely expensive to run continuously, we select particular markets to update each year. Digital data (social media and web analytics) is a continuous measurement that we can access whenever we want. However, it does not count people – but rather browsers or impressions. The GAM process converts digital data to represent people. These individual sources are brought together, and converted into individual adult weekly reach. The reach is de-duplicated- that is, people using multiple platforms to access our content (ie TV and radio or tablet and mobile) or multiple services (World Service English radio and World News TV channel) or languages (say, English and Swahili in Kenya) are counted only once. This has the net effect of lowering – and thereby making more accurate- our top level reach figure for each country, and therefore for the global reach figure. -

Disneynature Penguins Activity Packet

ACTIVITY PACKET Created in Partnership with Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment IN THEATERS EARTH DAY 2019 arrated by Ed Helms (The Office, The Hangover trilogy, The Daily Show with NJon Stewart), Disneynature’s all-new feature filmPenguins is a coming-of-age story about an Adélie penguin named Steve who joins millions of fellow males in the icy Antarctic spring on a quest to build a suitable nest, find a life partner and start a family. None of it comes easily for him, especially considering he’s targeted by everything from killer whales to leopard seals, who unapologetically threaten his happily ever after. From the filmmaking team behindBears and Chimpanzee, Disneynature’s Penguins opens in theaters and in IMAX® April 17, 2019. Acknowledgments Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment would like to take this opportunity to thank the amazing teams that came together to develop the Disneynature Penguins Activity Packet. It was created with great care, collaboration and the talent and hard work of many incredible individuals. A special thank you to Dr. Mark Penning for his ongoing support in developing engaging educational materials that connect families with nature. These materials would not have happened without the diligence and dedication of Kyle Huetter and Lacee Amos who worked side by side with the filmmakers and educators to help create these compelling activities and authored the unique writing found throughout each page. A big thank you to Hannah O’Malley and Michelle Mayhall whose creative thinking and artistry developed games and crafts into a world of outdoor exploration. Special thanks to director Jeff Wilson, director/producer Alastair Fothergill and producers Mark Linfield, Keith Scholey and Roy Conli for creating such an amazing story that inspired the activities found within this packet. -

BBC Script Agreement for Television and Online March 2017

SCRIPT AGREEMENT FOR TELEVISION AND ONLINE Memorandum of an Agreement made on 21st March 2017. Between The British Broadcasting Corporation whose principal office is at Broadcasting House Portland Place London W1A 1AA (the “BBC”, which term shall where the context so permits include the BBC’s assignees and successors in title including without limitation BBC Studios or any successor to BBC Studios, other production entity or co-producer, distributor, licensee or broadcaster) and The Personal Managers’ Association Limited whose registered office is at Summit House, 170 Finchley Road, London NW3 6BP (Company number 00487049) (the “PMA”) and The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain of First Floor 134 Tooley Street London SE1 2TU (the “WGGB”) establishing the minimum terms which shall be offered by the BBC on commissioning a Writer to write a Script for a television or online programme. 1 CONTENTS 1. Application of Agreement 2. Commissioning 3. Rights 4. Format Rights and Characters 5. Extracts 6. Script Payment and Secondary Channel Use 7. Repeat Fees on Primary Channels 8. Commercial Exploitation 9. Collective Administration 10. Miscellaneous Uses 11. Disputes Procedure 12. Regulation 13. Forum 14. Accounting 15. Publicity 16. Rewrites and Acceptance 17. Moral Rights and Alterations 18. Turnaround 19. Long Running Series 20. Credit 21. Copy of Programme 22. Attendance and Expenses 23. Confidentiality 24. Warranties and Indemnity 25. BBC’s Licensees 26. Term and Termination 27. Notices 28. Assignment 29. No Agency Partnership Joint Venture or Employment 30. Variation 31. Value Added Tax 32. Severability 33. Headings 34. Proper Law 35. Nature of the Agreement SCHEDULES 1.