Joseph Beuys' Unknown Gastrosophy Author(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September/October 2016 Volume 15, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 INSI DE Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Interview with Raqs Media Collective on the 2016 Shanghai Biennale Artist Features: Cui Xiuwen, Qu Fengguo, Ying Yefu, Zhou Yilun Buried Alive: Chapter 1 US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 C ONT ENT S 23 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Sophia Kidd 23 Qu Fengguo: Temporal Configurations Julie Chun 36 36 Cui Xiuwen Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky 48 Propositioning the World: Raqs Media Collective and the Shanghai Biennale Maya Kóvskaya 59 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Danielle Shang 48 67 Art Labor and Ying Yefu: Between the Amateur and the Professional Jacob August Dreyer 72 Buried Alive: Chapter 1 (to be continued) Lu Huanzhi 91 Chinese Name Index 59 Cover: Zhang Yu, One Man's Walden Pond with Tire, 2014, 67 performance, one day, Lijiang. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Chen Ping, David Chau, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist, and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Performance art has a strong legacy in FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum southwest China, particularly in the city EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian of Chengdu. Sophia Kidd, who previously EDITORS Julie Grundvig contributed two texts on performance art in this Kate Steinmann Chunyee Li region (Yishu 44, Yishu 55), updates us on an EDITORS (CHINESE VERSION) Yu Hsiao Hwei Chen Ping art medium that has shifted emphasis over the Guo Yanlong years but continues to maintain its presence CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde WEB SITE EDITOR Chunyee Li and has been welcomed by a new generation ADVERTISING Sen Wong of artists. -

Old Furnace Artist Residency: Art Is a Conjunction Jon William Henry James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2016 Old Furnace artist residency: Art is a conjunction Jon William Henry James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Sculpture Commons Recommended Citation Henry, Jon William, "Old Furnace artist residency: Art is a conjunction" (2016). Masters Theses. 105. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/105 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Old Furnace Artist Residency Jon Henry A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts School of Art, Design & Art History April 2016 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair : Greg Stewart Committee Members/ Readers: Stephanie Williams Rob Mertens Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... ii Intro ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Conceptual Background ...................................................................................................... 8 Pushback .......................................................................................................................... -

Art Analysis

Art Analysis Joseph Beuys 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks), starting 1982 In 1982 Joseph Beuys began his action/installation of 7000 Private collectors bought the stones, thereby financing the Oaks at the seventh edition of the contemporary art show planting of an oak tree in Kassel. This city is an extremely Documenta (held once every five years in Kassel) and it was symbolic place since it used to be the centre of arms pro- only finished, symbolically, by his son Wenzel at the next duction for all of Germany, a fact which caused it to be razed Documenta in 1987, one year after the artist’s death. to the ground during the Second World War. In reality this is a temporally undefined piece since its dura- Through this work, Beuys speaks of the need for a new and tion is programmed for only as long as the final surviving tree lasting alliance between man and nature but also of the of the 7000 mentioned in the title. Potentially this work could need to eradicate wars and to turn destructive energy into last until the end of the current ecosystem. building for society. On March 16, 1982 Beuys planted the first oak tree in the Today all the oak trees have been planted and the basalt centre of the Friederich Square in Kassel, right in front of the blocks put in place. Friedericianum, the building that traditionally hosts the main At the basis of 7000 Oaks there is a concept of transforma- section of the Documenta show. tion, an aspect that concerns both time, expressed symboli- The action originates from the following system: 7000 prism- cally through the oaks growth, and space, which undergoes shaped blocks of basalt coming from Kassel’s mining area were change as the trees develop. -

Project Report

Caroline Wendling / Oaks & Amity / 2014-2015 Project Report Oaks & Amity Caroline Wendling PROJECT REPORT 1. Introduction 2. The Artist and Shadow Curator Caroline Wendling Lotte Juul Petersen 3. The Project and Work Context The Project Events + Research 4. Main Event The White Wood Planting 5. Shadow Curator Report 6. Marketing Printed Material and Mail/Email Shots Advertising Online Marketing 7. Education / Outreach Programme Artist Talk The Gordon Schools Community Outreach Attendance Numbers 8. Media 9. Comments / Reflections / Evaluation Evaluation 10. Publication 11. Funding and Thanks 12. Appendix Oaks and Amity: Call for Proposal Action Plan for Oaks & Amity How to Plant a Tree Of Trees and Time, Alan Macpherson Notes from Kassel, Elisabetta Rattalino Project Report: Caroline Wendling, Oaks & Amity Oaks & Amity Caroline Wendling 1. Introduction Artist Caroline Wendling joined Deveron Arts in the autumn of 2014 to develop her project, Oaks & Amity; a project developed in response to the occasion of the centenary of the outbreak of World War One. It is a project that explored the link between ecology and art, between friendship and cooperation, precariousness and peace, one hundred years after the First World War. Through her investigation into the local history of both the First and Second World Wars, Caroline became particularly interested in the stories of local conscientious objectors and pacifists. Caroline worked with a multitude of local groups, including the Gordon Schools, Forestry Commission and war veterans, and produced a series of events exploring notions of peace and friendship in post war Europe. The major output of the project was the planting of a symbolic White Wood just outside Huntly. -

REMEDIATIONS. Art in Second Life"

Hz #11 - "REMEDIATIONS. Art in Second Life" HOME ARTICLES NET GALLERY --- --- REMEDIATIONS. Art in Second Life Domenico Quaranta Second Life [1]: hardly a day goes by without it being talked about. The media success of the virtual world launched in 2003 by the Californian company Linden Labs appears to be on a par only with its user popularity (around 10 million residents as I write) and commercial success. These three things are obviously closely connected: people flock to SL, companies follow, the media talks about it and this attracts new people and new companies. The hype – which strangely enough, as activist and media critic Geert Lovink [2] notes, is fed by "old school broadcast and print media and the wannabe cool corporations" is starting to show its first cracks [3], and while on the one hand it has served to make concepts like "avatar", "virtual worlds" and "social networks" popular, on the other, with its uncritical enthusiasm and superficiality, it has created false expectations that risk leading to an equally uncritical condemnation of a context that does have its problems, but is undeniably rich in potential. It's all true: the habitual users of SL represent a ludicrously tiny percentage of the 10 million curious visitors who set up an account for a single visit, without ever following it up; the only returns on the million dollar investments made by the big companies have been in terms of publicity, while their virtual headquarters are usually deserted; SL's graphic engine and scripting language are vastly inferior to those of other virtual worlds; its world is built around a trashy, kitsch aesthetic; the prevalent image is that of "a mega milkshake of pop culture" [4], and life revolves mainly around the banal repetition of real-life rituals (having sex, going dancing, and attending parties, openings and conferences) and the same principles: private property, wealth and consumption. -

New Practices, New Pedagogies

INNOVATIONS IN ART AND DESIGN NEW PRACTICES NEW PEDAGOGIES a reader EDITED BY MALCOLM MILES SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Printed in Copyright © 2004 …… All rights reserved. No part of this publication of the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publishers. Although all care is taken to ensure the integrity and quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the authors for any damage to properly or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. www ISBN ISSN The European League of Institutes of the Arts - ELIA - is an independent organisation of approximately 350 major arts education and training institutions representing the subject disciplines of Architecture, Dance, Design, Media Arts, Fine Art, Music and Theatre from over 45 countries. ELIA represents deans, directors, administrators, artists, teachers and students in the arts in Europe. ELIA is very grateful for support from, among others, The European Community for the support in the budget line 'Support to organisations who promote European culture' and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Published by SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Supported by the European Commission, Socrates Thematic Network ‘Innovation in higher arts education -

Installation Art and Experience

TRODUCTION INSTALLATION ART AND EXPERIENCE What is installation art? 'Installation art' is a term that loosely refers to the type of art into which the viewer physically enters, and which is often described as 'theatrical', 'immersive' or 'experiential'. However, the sheer diversity in terms of appearance, content and scope of the work produced today under this name, and the freedom with which the term is used, almost preclude it from having any meaning. The word 'installation' has now expanded to describe any arrangement of objects in any given space, to the point where it can happily be applied even to a conventional display of paintings on a wall. But there is a fine line between an installation of art and installation art. This ambiguity has been present since the terms first came into use in the 1960s. During this decade, the word 'installation' was employed by art magazines to describe the way in which an exhibition was arranged. The photographic documentation of this arrangement was termed an 'installation shot', and this gave rise to the use of the word for works that used the whole space as 'installation art'. Since then, the distinction between an installation of works of art and 'installation art' proper has become increasingly blurred. What both terms have in common is a desire to heighten the viewer's awareness of how objects are positioned (installed) in a space, and of our bodily response to this. However, there are also important differences. An installation of art is secondary in importance to the individual works it contains, while in a work of installation art, the space, and the ensemble of elements within it, are regarded in their entirety as a singular entity. -

Searching for Eur-‐Asia -‐ the Journeys of Joseph Beuys And

Searching for Eur-Asia - The Journeys of Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik Towards the Unity of Europe and Asia Shinya Watanabe An imaginary division between "East" and "West" was created in European cultural history, mainly to make a distinction between European Christianity and the alien cultures to its east. Even Emmanuel Levinas, known as a philosopher of the “other” in post-war Europe, was disdainful of Asia and Buddhism, and considered Europe to be central. Both Europe and Asia can exist in relation with what is to their east and west; neither can exist by itself. However, once a geographical and cultural entity is named “Europe” and “Asia,” or “West” and “East,” this creates an impression that such imaginary entities exist –, not in the relationship it has with its counterpart, but by itself. Containing Europe and Asia, Eurasia is one continuous mass of land. The idea of a fixed division between Europe and Asia has made it difficult for many to understand that East and West share historical and cultural roots in the Eurasian land mass. When the process of capturing the world via cogito, which originated in Christianity and prepared the way for European Modernity, was proven to be contradictory, contemporary art needed to reconsider the roots of modernity in order to find alternatives. So far, the vocabulary of contemporary art has addressed how to conceptually deal with the symbols created by the contradictions of modernity, but in the 21st century, the act of going back to the origin of such contradictions will be the basis for a new vocabulary. -

Joseph Beuys 1 Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys 1 Joseph Beuys Joseph Beuys Offset poster for Beuys' 1974 US lecture-series "Energy Plan for the Western Man", organised by Ronald Feldman Gallery - Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York Born May 12, 1921Krefeld, Germany Died January 23, 1986 (aged 64)Düsseldorf Nationality German Field Performances, sculpture, visual art, aesthetics, social philosophy Training Kunstakademie Düsseldorf Joseph Beuys (German pronunciation: [ˈjoːzɛf ˈbɔʏs]; May 12, 1921, Krefeld – January 23, 1986, Düsseldorf) was a German performance artist, sculptor, installation artist, graphic artist, art theorist and pedagogue of art. His extensive work is grounded in concepts of humanism, social philosophy and anthroposophy; it culminates in his "extended definition of art" and the idea of social sculpture as a gesamtkunstwerk, for which he claimed a creative, participatory role in shaping society and politics. His career was characterized by passionate, even acrimonious public debate, but he is now regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.[1] [2] Biography Childhood and early life in the Third Reich (1921-1941) Joseph Beuys was the son of the merchant Josef Jakob Beuys (1888–1958) and Johanna Maria Margarete Beuys (born Hülsermann, 1889–1974). The parents had moved from Geldern to Krefeld in 1910, and Beuys was born there on May 12, 1921. In autumn of that year the family moved to Kleve, an industrial town in the Lower Rhine region of Germany, close to the Dutch border. There, Joseph attended primary school (Katholische Volksschule) and secondary/high- school (Staatliches Gymnasium Cleve, now the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gymnasium). His teachers considered him to have a talent for drawing; he also took piano- and cello lessons. -

Art & the Anthropocene

Art & The Anthropocene Processes of responsiveness and communication in an era of environmental uncertainty A project submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer Holly Rae (Jen Rae) M.A. (Public Art), B.F.A. School of Art College of Design and Social Context RMIT University March 2015 DECLARATION I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; and; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Jennifer Holly Rae 13 March 2015 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their dedicated guidance and support during my candidature: Associate Professor Linda Williams (Primary Supervisor) Simon Perry (former Secondary Supervisor) Dr. Irene Barberis-Page (Secondary Supervisor) Professor Lesley Duxbury Thank you to my colleagues of The Riparian Project, Nicola Rivers and Amanda Wealands, for all of your enthusiasm, industriousness and rigor in shaping the project over the past 4+ years. I would also like to recognise support for The Riparian Project from the following: The Centre for Sustainability Leadership RMIT University SEEDS program including Marcus Powe and Ian Jones The School for Social Entrepreneurs Russell Wealands and The Yea Wetlands Trust and Committee of Management The Yea Public Art Advisory Committee (PAAG) members Pilot project partners Mary Crooks and Liz McAloon from The Victorian Women’s Trust For technical and logistical support, thank you to Thomas Ryan, Erik North, Michael Wentworth-Bell and Alan Roberts. -

Performance Art Context R

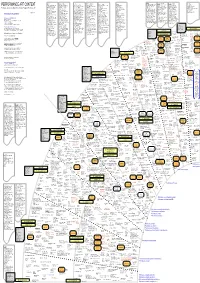

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

MATERIAL ZONES Gaston Bachelard Imagination and Matter, 1942//022

MATERIAL ZONES EVOLUTIONARY IDEAS Gaston Bachelard Imagination and Matter, 1942//022 Henri Bergson Creative Evolution, 1907//078 Walter De Maria On the Importance of Natural Vladimir Vernadsky The Biosphere, 1926//079 Disasters, 1960//024 Jacques Monod Chance and Necessity, 1970//081 Robert Smithson In Conversation with Dennis Wheeler, Gregory Bateson Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 1972//085 1969–70//025 Arne Naess The Three Great Movements, 1992//090 Hans Haacke Systems Aesthetics: Conversation with Félix Guattari The Three Ecologies, 1989//092 Jeanne Siegel, 1971//028 Peter Halley Nature and Culture, 1983//98 Suzaan Boettger Looking at, and Overlooking, Women Trevor Paglen Experimental Geography, 2008//104 Working in Land Art in the 1970s, 2008//031 Claire Bishop, Lynne Cooke, Tim Griffin, Pierre Huyghe, Ana Mendieta In Conversation with Linda Montano, Pamela M. Lee, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Andrea Zittel 1988//035 Remote Possibilities: Land Art’s Changing Terrain, Michael Auping A Nomad among Builders, 1987//036 2005//107 Jean-François Lyotard Scapeland, 1988//038 Helen & Newton Harrison On Ecocivility, 2009//113 David Harvey Between Space and Time, 1990//040 Tomás Saraceno In Conversation with Stefano Boeri and Mierle Laderman Ukeles Flow City (1983–91), 1995//042 Hans Ulrich Obrist, 2005//116 Steven Connor Topologies: Michel Serres and the Ingeborg Reichle Art in the Age of Technoscience, Shapes of Thought, 2002//044 2009//118 Emma Cocker Heather and Ivan Morison: Earthwalker, Oliver Grau The History of Telepresence: Automata, 2006//049