Sharples on Goldensohn, 'The Nuremberg Interviews'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

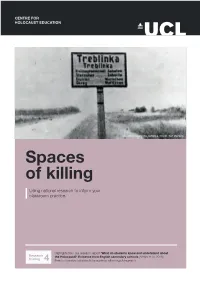

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom Through German-Jewish Eyes

Chapter 4 The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom through German-Jewish Eyes Alan E. Steinweis The November 1938 pogrom, often referred to as the “Kristallnacht,” was the largest and most significant instance of organized anti-Jewish violence in Nazi Germany before the Second World War.1 In addition to the massive destruc- tion of synagogues and property, the pogrom involved the physical abuse and terrorizing of German Jews on a massive scale. German police reported an official death toll of 91, but the actual number of Jews killed was probably about ten times that many when one includes fatalities among Jews who were treated brutally during their arrest and subsequent imprisonment in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.2 Violence had been a normal feature of the Nazi regime’s anti-Jewish measures since 1933,3 but the scale and intensity of the Kristallnacht were unprecedented. The pogrom occurred less than one year before the outbreak of the war and the first atrocities by the Wehrmacht against Polish Jews, and less than three years before the Einsatzgruppen, Order Police, and other units began to undertake the mass murder of Jews in the Soviet Union. Knowledge about the perpetrators of the pogrom, therefore, pro- vides important context for understanding the violence that came later. To be sure, nobody has yet undertaken the extremely ambitious project to identify precisely which perpetrators of the Kristallnacht eventually would participate directly in the “Final Solution.” There certainly were many such cases, however, perhaps the most notable being Odilo Globocnik, who presided over the po- grom violence in Vienna in November 1938 and less than three years later was placed in charge of Operation Reinhardt, the mass murder of the Jews in the General Government.4 1 Many of the observations in this chapter are based on cases described and documented in the author’s book, Kristallnacht 1938 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). -

Final Statements from the Defendants

TWO HUNDRED AND SIXTEENTH DAY Saturday, 31 August 1946 Final statements from the defendants Ernst Kaltenbrunner THE PRESIDENT: I call upon the Defendant Ernst Kaltenbrunner. ERNST KALTENBRUNNER (Defendant): The Prosecution holds me responsible for the concentration camps, for the destruction of Jewish life, for Einsatzgruppen and other things. All of this is neither in accord with the evidence nor with the truth. The accusers as well as the accused are exposed to the dangers of a summary proceeding. It is correct that I had to take over the Reich Security Main Office. There was no guilt in that in itself. Such offices exist in governments of other nations too. However, the task and activity assigned to me in 1943 consisted almost exclusively in the reorganization of the German political and military intelligence service, though not as Heydrich's successor. Almost a year after his death I had to accept this post under orders and as an officer at a time when suspicion fell on Admiral Canaris of having collaborated with the enemy for years. In a short time I ascertained the treason of Canaris and his accomplices to the most frightful extent. Offices IV and V of the Reich Security Main Office were subordinate to me only theoretically, not in fact. The chart shown here of the different groups and the chain of command leading from them is wrong and misleading. Himmler, who understood in a masterly way how the SS, which for a long time had ceased to, form an organizational and ideological unit, could be split up into very small groups and brought under his immediate influence, so far as it served his purpose, together with Mueller, the Chief of the Gestapo, committed the crimes which we 378 31 Aug. -

Local Agency and Individual Initiative in the Evolution of the Holocaust: the Case of Heinrich Himmler

Local Agency and Individual Initiative in the Evolution of the Holocaust: The Case of Heinrich Himmler By: Tanya Pazdernik 25 March 2013 Speaking in the early 1940s on the “grave matter” of the Jews, Heinrich Himmler asserted: “We had the moral right, we had the duty to our people to destroy this people which wanted to destroy us.”1 Appointed Reichsführer of the SS in January 1929, Himmler believed the total annihilation of the Jewish race necessary for the survival of the German nation. As such, he considered the Holocaust a moral duty. Indeed, the Nazi genocide of all “life unworthy of living,” known as the Holocaust, evolved from an ideology held by the highest officials of the Third Reich – an ideology rooted in a pseudoscientific racism that rationalized the systematic murder of over twelve million people, mostly during just a few years of World War Two. But ideologies do not murder. People do. And the leader of the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler, never personally murdered a single Jew. Instead, he relied on his subordinates to implement his often ill-defined visions. Thus, to understand the Holocaust as a broad social phenomenon we must refocus our lens away from an obsession with Hitler and onto his henchmen. One such underling was indeed Himmler. The problem in the lack of consensus among scholars is over the matter of who, precisely, bears responsibility for the Holocaust. Historians even sharply disagree about the place of Adolf Hitler in the decision-making processes of the Third Reich, particularly in regards to the Final Solution. -

Special Motivation - the Motivation and Actions of the Einsatzgruppen by Walter S

Special Motivation - The Motivation and Actions of the Einsatzgruppen by Walter S. Zapotoczny "...Then, stark naked, they had to run down more steps to an underground corridor that Led back up the ramp, where the gas van awaited them." Franz Schalling Einsatzgruppen policeman Like every historical event, the Holocaust evokes certain specific images. When mentioning the Holocaust, most people think of the concentration camps. They immediately envision emaciated victims in dirty striped uniforms staring incomprehensibly at their liberators or piles of corpses, too numerous to bury individually, bulldozed into mass graves. While those are accurate images, they are merely the product of the systematization of the genocide committed by the Third Reich. The reality of that genocide began not in the camps or in the gas chambers but with four small groups of murderers known as the Einsatzgruppen. Formed by Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfuhrer-SS, and Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), they operated in the territories captured by the German armies with the cooperation of German army units (Wehrmacht ) and local militias. By the spring of 1943, when the Germans began their retreat from Soviet territory, the Einsatzgruppen had murdered 1.25 million Jews and hundreds of thousands of Polish, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian and Soviet nationals, including prisoners of war. The Einsatzgruppen massacres preceded the invention of the death camps and significantly influenced their development. The Einsatzgruppen story offers insight into a fundamental Holocaust question of what made it possible for men, some of them ordinary men, to kill so many people so ruthlessly. The members of the Einsatzgruppen had developed a special motivation to kill. -

Poland Study Guide Poland Study Guide

Poland Study Guide POLAND STUDY GUIDE POLAND STUDY GUIDE Table of Contents Why Poland? In 1939, following a nonaggression agreement between the Germany and the Soviet Union known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was again divided. That September, Why Poland Germany attacked Poland and conquered the western and central parts of Poland while the Page 3 Soviets took over the east. Part of Poland was directly annexed and governed as if it were Germany (that area would later include the infamous Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz- Birkenau). The remaining Polish territory, the “General Government,” was overseen by Hans Frank, and included many areas with large Jewish populations. For Nazi leadership, Map of Territories Annexed by Third Reich the occupation was an extension of the Nazi racial war and Poland was to be colonized. Page 4 Polish citizens were resettled, and Poles who the Nazis deemed to be a threat were arrested and shot. Polish priests and professors were shot. According to historian Richard Evans, “If the Poles were second-class citizens in the General Government, then the Jews scarcely Map of Concentration Camps in Poland qualified as human beings at all in the eyes of the German occupiers.” Jews were subject to humiliation and brutal violence as their property was destroyed or Page 5 looted. They were concentrated in ghettos or sent to work as slave laborers. But the large- scale systematic murder of Jews did not start until June 1941, when the Germans broke 2 the nonaggression pact with the Soviets, invaded the Soviet-held part of Poland, and sent 3 Chronology of the Holocaust special mobile units (the Einsatzgruppen) behind the fighting units to kill the Jews in nearby forests or pits. -

Contemporary Views on the Holocaust

Contemporary Views on the Holocaust Randolph L. Braham, Editor .,~ KluweroNijhoff Publishing a member of the Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Boston The Hague Dordrecht Lancaster Distributors for North America: Kluwer Boston, Inc. 190 Old Derby Street Hingham, MA 02043, U.S.A Distributors outside North America: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Distribution Centre P.O. Box 322 3300AH Dordrecht, The Netherlands Ubrary of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Contemporary views on the Holocaust. (Holocaust studies series) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939~ 1945) - Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939~1945) - Historiography - Addresses, essays, lectures. Braham, Randolph L. II. Senes. D810.J4C67 1983 940.53'15'03924 83-177 IS8N·13: 978·94-009·6683-3 e·IS8N·13 978-94-009-6681·9 001: 10.1007/978·94·009-6681·9 Copyright © 1983 by Kluwer·Nijhoff Publishing No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means without written permission of the publisher. Holocaust Studies Series Randolph L. Braham, Series Editor The Graduate School and University Center, The City University of New York Previously published: Perspectives on the Holocaust, 1983 The Holocaust Studies Series is published in cooperation with the Jack P. Eisner Institute for Holocaust Studies. These books are outgrowths of lectures, conferences, and research projects sponsored by the Institute. It is the purpose of the series to subject the events and circumstances of the Holocaust to scrutiny by a variety of academics who bring different scholarly disciplines to the study. Contemporary Views on the Holocaust Contents Preface by Randolph L. -

Schoen Consulting Claims Conference Holocaust Topline – AUSTRIA, US, CANADA March 2019 Screening Questions

Schoen Consulting Claims Conference Holocaust Topline – AUSTRIA, US, CANADA March 2019 Screening Questions United States Canada Austria • {Age} 18 and older 100% Under 18 [TERMINATE] --1 General Awareness - Open Ended Questions Intro: Thank you for your participation in this survey. The next questions in the survey are about a particular historical topic – the Holocaust. These questions don’t have right or wrong answers, so please be as honest and open as you can. 1. Have you ever seen or heard the word Holocaust before? Yes, I have definitely heard about the 89% 85% 87% Holocaust Yes, I think I’ve heard about the Holocaust 7% 9% 9% No, I don’t think I have heard about the 3% 3% 2% Holocaust No, I definitely have not heard about the 1% 3% 2% Holocaust IF NO, SKIP TO Q9 2. In your own words, what does the term Holocaust refer to? OPEN ENDED WITH PRECODES (MULTIPLE ANSWERS ACCEPTED) Extermination of the Jews/Jewish people 62% 64% 58% Genocide generally 18% 19% 27% World War II 4% 32% 16% The Nazis 3% 24% 7% Adolf Hitler 3% 15% 6% Other 14% 8% 15% Not sure 3% 4% 5% 1 Throughout this document “--” indicates no response while a “blank space” indicates that the question or answer choice was not asked in that specific country. Schoen Consulting Claims Conference Holocaust Topline – AUSTRIA, US, CANADA March 2019 United States Canada Austria 3. Who or what do you think caused the Holocaust? OPEN ENDED WITH PRECODES (MULTIPLE ANSWERS ACCEPTED) Adolf Hitler 83% 48% 39% The Nazis 67% 19% 21% Jews 10% 3% 8% World War I 6% 3% 4% Germany 36% 12% 2% Antisemitism -- -- 2% Other 1% 18% 19% Not sure 4% 8% 6% 4. -

Der Reichsgau Wartheland in Den Jahren 1939–1945

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS WRATISLAVIENSIS No 3840 Studia nad Autorytaryzmem i Totalitaryzmem 40, nr 2 Wrocław 2018 DOI: 10.19195/2300-7249.40.2.4 WOJCIECH WICHERT Oddziałowe Biuro Badań Historycznych IPN w Szczecinie ORCiD: 0000-0003-1335-592X „Exerzierplatz des Nationalsozialismus“ — der Reichsgau Wartheland in den Jahren 1939–1945 Kein anderes Land befand sich so lange unter der Besatzung des Dritten Reiches wie Polen. Polen war das erste Opfer der deutschen Aggression und hat als erstes Land unter großen Opfern zuerst bewaffneten Widerstand geleistet und später in den Jahren 1939–1945 beispiellose Personen-, Kultur- und Materialver- luste erlitten. Der deutsche Überfall auf Polen im September 1939, die Einstel- lung und die Verbrechen gegenüber Polen waren eine Form von Ausführung des antislawischen Rassismus. Die neueren Forschungen, insbesondere die, die seit den neunziger Jahren geführt wurden, offenbaren die tatsächliche Größe der ver- brecherischen Politik gegenüber den slawischen Völkern. Sie zeigen, wie sich der deutsche Nationalismus zum Rassismus entwickelt hat, das Ziel verfolgend die slawische Bevölkerung durch die nationalsozialistische Germanisierungspolitik aus ihrer Heimat zu vertreiben und sie durch die „höhere arische Rasse“ zu be- siedeln1. Diese Maßnahmen der Besatzung wurden in den schon vor dem Krieg ausgearbeiteten Generalplan Ost aufgenommen, in ein großangelegtes Kolonisie- rungs- und Germanisierungsprojekt der Gebiete in Ostmitteleuropa und in Ost- europa, das mit der Aussiedlung beziehungsweise mit der Eliminierung der hier niedergelassenen slawischen Bevölkerung verbunden war2. Vor allem aus dieser 1 A. Wolff-Powęska, Pamięć, brzemię i uwolnienie. Niemcy wobec nazistowskiej przeszłości (1945–2010) [Erinnerung — Last und Befreiung. Die Deutschen gegenüber die nationalsozialisti- schen Vergangenheit (1945–2010)], Poznań 2011, S. -

Zum Selbstverständnis Von Frauen Im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück

Zum Selbstverständnis von Frauen im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück. von der Fakultät I Geisteswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Berlin genehmigte Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt von Silke Schäfer aus Berlin D 83 Berichter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Benz Berichterin: Prof. Dr. Johanna Bleker (FUB) Tag der Wissenschaftlichen Aussprache 06. Februar 2002 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 4 1 Problemfelder und Nachkriegsprozesse 11 1.1 Begriffsklärung 11 1.1.1 Sprache 13 1.1.2 Das nationalsozialistische "Frauenbild" 14 1.1.3 Täterinnen 18 1.1.4 Kategorien für Frauen im Konzentrationslager 19 1.1.5 Auswahlkriterien 26 1.2 Strafverfolgung 28 1.2.1 Militärgerichtsverfahren 29 1.2.2 Die Hamburger Ravensbrück-Prozesse 32 1.2.3 Strafverfahren vor deutschen Gerichten 38 1.2.4 Strafverfahren vor anderen Gerichten 40 2 Topographie 42 2.1 Vorgeschichte 42 2.1.1 Moringen 42 2.1.2 Lichtenburg 45 2.2 Das Frauen-KZ Ravensbrück 47 2.2.1 "Alltagsleben" 52 2.2.2 Solidarität 59 2.3 Arbeit 62 2.3.1 Arbeitskommandos 63 2.3.2 Wirtschaftliche Ausbeutung 64 2.3.3 Lagerbordelle und SS-Bordelle 69 2.4 Aufseherinnen 75 2.4.1 Strafen 77 2.5 Lager bei Ravensbrück 80 2.5.1 Männerlager 81 2.5.2 Jugendschutzlager Uckermark 81 3 Die Medizin 86 3.1 Der Blick auf die Mediziner 86 3.1.1 Das Revier 87 3.2 Medizinische Experimente 89 3.2.1 Sulfonamidversuche / Knochen-, 91 Muskel- und Nervenoperation Sulfonamidversuche 93 Knochen-, Muskel- und Nervenoperation 104 Versuche 108 3.3 Sterilisation 110 3.3.1 Geburten und Kinder 115 3.4 Das medizinische Personal 123 3.4.1 NS-Ärztinnen - Lebensskizzen 125 Jantzen geb. -

Anti-Jewish Laws Timeline

Materials ANTI-JEWISH LAWS TIMELINE This Jewish storefront was vandalised during Kristallnacht in Magdeburg, Germany, November 9-10, 1938. (Montreal Holocaust Museum Collection) 1933 1935 1938 1939 1940 1941-1942 January 30, 1933 1935 April 26, 1938 November 9-10, 1938 September 1, 1939 May 20, 1940 June 1941 to January 1942 Adolf Hitler is appointed The Law for the Protection of Nazis force Jews to register Kristallnacht: A wave of Invasion of Poland: Germany The Auschwitz concentration camp Following the German invasion of the Chancellor of Germany. German Blood and Honour their assets, a first step toward state-organised attacks attacks Poland and World War II opens in occupied Poland. It will Soviet Union, four Einsatzgruppen and the German Citizenship total exclusion from the target Jewish businesses, begins. By the end of the month, eventually become a mixed camp (mobile killing units) massacre 1 February 28, 1933 Law are passed. Known German economy. synagogues, apartments Poland is divided between (concentration and death camp) million Jews. Using the Reichstag (German as the “Nuremberg Laws”, across Germany and Austria. Germany and the USSR. Jews where nearly 1 million Jews are parliament) fire as pretext, Hitler they prohibit marriage and July 25, 1938 Jews are forced to pay fines on the German side are almost murdered. issues emergency decrees sexual relationships between Jewish doctors are forbidden of over one billion German immediately subjected to anti- that mark the end of all basic Germans and Jews and state to treat ‘Aryan’ patients marks. Jewish measures. freedoms, including freedom of that only persons of “German speech, press, assembly and or related blood” can be August 17, 1938 November 15, 1938 October 28, 1939 citizens.