Hip-Hop's Tanning of a Postmodern America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Autoethnography of Scottish Hip-Hop: Identity, Locality, Outsiderdom and Social Commentary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Napier An autoethnography of Scottish hip-hop: identity, locality, outsiderdom and social commentary Dave Hook A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Declaration This critical appraisal is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It has not been previously submitted, in part or whole, to any university or institution for any degree, diploma, or other qualification. Signed:_________________________________________________________ Date:______5th June 2018 ________________________________________ Dave Hook BA PGCert FHEA Edinburgh i Abstract The published works that form the basis of this PhD are a selection of hip-hop songs written over a period of six years between 2010 and 2015. The lyrics for these pieces are all written by the author and performed with hip-hop group Stanley Odd. The songs have been recorded and commercially released by a number of independent record labels (Circular Records, Handsome Tramp Records and A Modern Way Recordings) with worldwide digital distribution licensed to Fine Tunes, and physical sales through Proper Music Distribution. Considering the poetics of Scottish hip-hop, the accompanying critical reflection is an autoethnographic study, focused on rap lyricism, identity and performance. The significance of the writing lies in how the pieces collectively explore notions of identity, ‘outsiderdom’, politics and society in a Scottish context. Further to this, the pieces are noteworthy in their interpretation of US hip-hop frameworks and structures, adapted and reworked through Scottish culture, dialect and perspective. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

James Edwin Pope

James Edwin Pope EXPERIENCE ─────────────────────────────────────────────────── Toyota (Demo) Husband (Lead) Commercial 2019 Amtrak Traveler (Lead) Commercial 2019 The Greatest Sketch Show in America Actor (Various Roles) Theatre 2019 Centra Health Father (Lead) Commercial 2019 Maryland Pride Be Like Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2019 United Airlines Husband (Lead) Commercial 2018 Canon, Inc. Father (Lead) Commercial 2018 Moxy by Marriott Hotels Interior Designer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Maryland Live! Casino Casino Patron (Lead) Print 2018 Black and Decker Homeowner (Lead) Print 2018 Giant Foods Party-Goer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Thompson Creek Windows Homeowner (Lead) Commercial 2018 Dark City: Beneath the Beat Police Officer/Dancer Film 2018 New Year’s Daze Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Film (Short) 2017 Epic Office XMas Party Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Microtel by Wyndham Hotels Father (Lead) Print 2017 Time Machine Dancer/Writer Theatre 2017 Tinder On-Demand Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2017 The Motion Challenge Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Political Dance Battle Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Cards Against Humanity IRL (Web Series) Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Heroes and Villains Dancer Theatre 2016 New Year (Parody) Director/Writer Film (Short) 2016 Steve Harvey Show Guest Television 2016 The Today Show Guest Television 2015 Countertop Solutions Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Commercial 2015 WORK EXPERIENCE ──────────────────────────────────────────────────── Krewski, LLC Founder -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

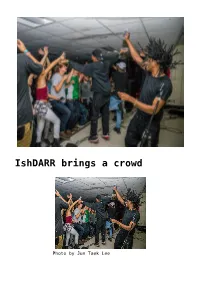

Ishdarr Brings a Crowd,Iowa Band Speaks on Locality,Field Report To

IshDARR brings a crowd Photo by Jun Taek Lee A packed crowd gathered in Gardner on Friday, Nov. 6, to hear from three young hip-hop artists—Young Eddy, Kweku Collins and IshDARR (pictured to the left). IshDARR is based out of Milwaukee, Wis. The sharp-tongued 19- year-old released a critically acclaimed album, “Old Soul, Young Spirit,” earlier this year. He largely pulled material from that album during the performance. The youthful, ecstatic energy of his recorded material transferred seamlessly to the stage. IshDARR was totally engaging for the duration of the set and did not shy away from talking with the audience, eliciting laughter and cheers. It wasn’t a terribly long set, but one that kept the people in attendance rapt from start to finish. Milwaukee is an exciting place to be an MC in 2015. The Midwestern city has recently cultivated a vibrant and dynamic DIY hip hop scene that’s only getting larger. IshDaRR, one of the youngest and most prominent members of the scene, proved on Friday night that he’s got a lot to share with the world. Assuredly, he is only getting started. Friday night was the third time that Young Eddy, aka Greg Margida ’16, has performed on campus and he is sure to have more performances next semester. Kweku Collins hails from Evanston, Ill., and this was his first time performing in Grinnell. Iowa band speaks on locality The S&B’s Concerts Correspondent Halley Freger ‘17 sat down with Pelvis’ guitarist and vocalist, Nao Demand, before his Gardner set on Friday, Oct. -

Chris Cunningham: Autoria Em Videoclipe

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PROGRAMA DE ESTUDOS PÓS-GRADUADOS EM COMUNICAÇÃO E SEMIÓTICA CHRIS CUNNINGHAM: AUTORIA EM VIDEOCLIPE Sueli Chaves Andrade São Paulo 2009 Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica CHRIS CUNNINGHAM: AUTORIA EM VIDEOCLIPE Sueli Chaves Andrade Dissertação apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de MESTRE em Comunicação e Semiótica, sob a orientação do Professor Doutor Arlindo Ribeiro Machado Neto. São Paulo 2009 SUELI CHAVES ANDRADE CHRIS CUNNINGHAM: AUTORIA EM VIDEOCLIPE Dissertação apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de MESTRE em Comunicação e Semiótica, sob a orientação do Professor Doutor Arlindo Ribeiro Machado Neto. Aprovado pela Banca Examinadora em ____________________________2009 BANCA EXAMINADORA _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Dedico a meu pai, Antônio Andrade, maior incentivador dos meus sonhos de vida. Agradecimentos Sem generosidade, eu jamais teria concluído essa dissertação. E eu a recebi de diferentes pessoas, momentos e lugares. Agradeço em primeiro lugar a generosidade da minha mãe e irmãs, que nos momentos mais difíceis na luta do meu pai contra o câncer, tiveram a nobreza de segurar as pontas mesmo eu estando ausente. Agradeço a generosidade de Mari, parceira incondicional nos meus melhores e piores momentos nesses últimos dois anos. Agradeço a generosidade dos amigos que me acolheram de afeto e de fato, Rodrigo e Ana. Obrigada a meu orientador Arlindo Machado, por todo a ajuda na concretização das minhas idéias vagas e imaturas. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

List of Lintenings

• Iceberg Slim "Duriella DuFontaine" • Lightnin Hopkins "Dirty Dozens" • Lightnin' Rod/Jimi Hendrix "Duriella DuFontaine" • Watts Prophets "The Days The Hours" • Count Machuki and the Sound Dimension "More Scorcha" • Jimmy Castor "It's Just Begun" • Gil Scott-Heron "The Bottle" • Thin Lizzy "Johnny the Fox" • Harlem Underground Band "Cheeba Cheeba" • Cheryl Lynn "To Be Real" • Blowfly "Blowfly's Rap" • Incredible Bongo Band “Apache" • Fatback Band "King Tim III" • Sugarhill Gang "8th Wonder" • Funky 4 + 1 "That's the Joint" • Kurtis Blow "The Breaks" • Fearless Four "Rockin It" • Younger Generation "We Rap More Mellow" (actually Furious Five) • Sequence "Funk You Up" • Treacherous Three "Feel the Heartbeat" • Afrika Bambaataa "Death Mix" • Afrika Bambaataa "Jazzy Sensation" • Kraftwerk "Trans Europe Express” • Run DMC "Sucker MCs", TV performance (vs Kool Moe Dee/Special K on "Graffiti Rock") • Eric B and Rakim "My Melody" • Ultramagnetic MCs "Ego Trippin" • Juice Crew "The Symphony" • MC Shan "The Bridge" • Boogie Down Productions "The Bridge is Over" • LL Cool J "Rock the Bells" • Jody Watley "Friends" • Newcleus "Jam On It" • Salt N Pepa "Tramp" • De La Soul "Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey)" • A Tribe Called Quest "Description of a Fool" • Jungle Brothers "I'll House You” • Ed OG "Be a Father to Your Child" • JVC Force "Strong Island" • Main Source "Looking at the Front Door” • BDP "Criminal Minded" • Public Enemy "911 is a Joke" • Schoolly D "Saturday Night" • Schooly D "Black Enough For You" • NWA "Gangsta Gangsta" • NWA "Express Yourself" • JJ Fad "Supersonic" • DJ Quik "Tonight" • Geto Boys "Damn It Feels Good to be a Gangster" • The D.O.C. -

2019 JUNO Award Nominees

2019 JUNO Award Nominees JUNO FAN CHOICE AWARD (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Universal Avril Lavigne BMG*ADA bülow Universal Elijah Woods x Jamie Fine Big Machine*Universal KILLY Secret Sound Club*Independent Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony NAV XO*Universal Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Growing Pains Alessia Cara Universal Not A Love Song bülow Universal Body Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony In My Blood Shawn Mendes Universal Pray For Me The Weeknd, Kendrick Lamar Top Dawg Ent*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Camila Camila Cabello Sony Invasion of Privacy Cardi B Atlantic*Warner Red Pill Blues Maroon 5 Universal beerbongs & bentleys Post Malone Universal ASTROWORLD Travis Scott Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Darlène Hubert Lenoir Simone* Select These Are The Days Jann Arden Universal Shawn Mendes Shawn Mendes Universal My Dear Melancholy, The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Outsider Three Days Grace RCA*Sony ARTIST OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Alessia Cara Universal Michael Bublé Warner Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Arkells Arkells*Universal Chromeo Last Gang*eOne Metric Metric Music*Universal The Sheepdogs Warner Three Days Grace RCA*Sony January 29, 2019 Page 1 of 9 2019 JUNO Award Nominees -

THE WHITE STRIPES – the Hardest Button to Button (2003) ROLLING STONES – Like a Roling Stone (1995) I AM – Je Danse Le

MICHEL GONDRY DIRECTORS LABEL DVD http://www.director-file.com/gondry/dlabel.html DIRECTOR FILE http://www.director-file.com/gondry/ LOS MEJORES VIDEOCLIPS http://www.losmejoresvideoclips.com/category/directores/michel-gondry/ WIKIPEDIA http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_Gondry PARTIZAN http://www.partizan.com/partizan/home/ MIRADAS DE CINE 73 http://www.miradas.net/2008/n73/actualidad/gondry/gondry.html MIRADAS DE CINE 73 http://www.miradas.net/2008/n73/actualidad/gondry/rebobineporfavor1.html BACHELORETTE - BJORK http://www.director-file.com/gondry/bjork6.html THE WHITE STRIPES – The hardest button to button (2003) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/stripes3.html ROLLING STONES – Like a Roling Stone (1995) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/stones1.html I AM – Je danse le mia (1993) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/iam.html JEAN FRANÇOISE COHEN – La tour de Pise (1993) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/coen.html LUCAS - Lucas With the Lid off (1994) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/lucas.html CHRIS CUNNINGHAM DIRECTORS LABEL DVD http://www.director-file.com/cunningham/dlabel.html LOS MEJORES VIDEOCLIPS http://www.losmejoresvideoclips.com/category/directores/chris-cunningham/ POP CHILD http://www.popchild.com/Covers/video_creators/chris_cunningham.htm WEB PERSONAL AUTOR http://chriscunningham.com/ WIKIPEDIA http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chris_Cunningham ARTFUTURA http://www.artfutura.org/02/arte_chris.html APHEX TWIN – Come to Daddy (1997) http://www.director-file.com/cunningham/aphex1.html SPIKE JONZE WEB PERSONAL http://spikejonze.net/