The History of Deaf Education and ASL Part 1 1. the History of Deaf Education and ASL an Important Part of Learning a Language I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Sasl) in a Bilingual-Bicultural Approach in Education of the Deaf

APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF Philemon Abiud Okinyi Akach August 2010 APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF By Philemon Abiud Omondi Akach Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (DEPARTMENT OF AFROASIATIC STUDIES, SIGN LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE PRACTICE) at the UNIVERSITY OF FREE STATE Promoter: Dr. Annalie Lotriet. Co-promoter: Dr. Debra Aarons. August 2010 Declaration I declare that this thesis, which is submitted to the University of Free State for the degree Philosophiae Doctor, is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me to another university or faculty. I hereby cede the copyright of the thesis to the University of Free State Philemon A.O. Akach. Date. To the deaf children of the continent of Africa; may you grow up using the mother tongue you don’t acquire from your mother? Acknowledgements I would like to say thank you to the University of the Free State for opening its doors to a doubly marginalized language; South African Sign Language to develop and grow not only an academic subject but as the fastest growing language learning area. Many thanks to my supervisors Dr. A. Lotriet and Dr. D. Aarons for guiding me throughout this study. My colleagues in the department of Afroasiatic Studies, Sign Language and Language Practice for their support. Thanks to my wife Wilkister Aluoch and children Sophie, Susan, Sylvia and Samuel for affording me space to be able to spend time on this study. -

Deaf-History-Part-1

[from The HeART of Deaf Culture: Literary and Artistic Expressions of Deafhood by Karen Christie and Patti Durr, 2012] The Chain of Remembered Gratitude: The Heritage and History of the DEAF-WORLD in the United States PART ONE Note: The names of Deaf individuals appear in bold italics throughout this chapter. In addition, names of Deaf and Hearing historical figures appearing in blue are briefly described in "Who's Who" which can be accessed via the Overview Section of this Project (for English text) or the Timeline Section (for ASL). "The history of the Deaf is no longer only that of their education or of their hearing teachers. It is the history of Deaf people in its long march, with its hopes, its sufferings, its joys, its angers, its defeats and its victories." Bernard Truffaut (1993) Honor Thy Deaf History © Nancy Rourke 2011 Introduction The history of the DEAF-WORLD is one that has constantly had to counter the falsehood that has been attributed to Aristotle that "Those who are born deaf all become senseless and incapable of reason."1 Our long march to prove that being Deaf is all right and that natural signed languages are equal to spoken languages has been well documented in Deaf people's literary and artistic expressions. The 1999 World Federation of the Deaf Conference in Sydney, Australia, opened with the "Blue Ribbon Ceremony" in which various people from the global Deaf community stated, in part: "...We celebrate our proud history, our arts, and our cultures... we celebrate our survival...And today, let us remember that many of us and our ancestors have suffered at the hands of those who believe we should not be here. -

Deaf American Historiography, Past, Present, and Future

CRITICAL DISABILITY DISCOURSES/ 109 DISCOURS CRITIQUES DANS LE CHAMP DU HANDICAP 7 The Story of Mr. And Mrs. Deaf: Deaf American Historiography, Past, Present, and Future Haley Gienow-McConnella aDepartment of History, York University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a review of deaf American historiography, and proposes that future scholarship would benefit from a synthesis of historical biography and critical analysis. In recent deaf historical scholarship there exists a tendency to privilege the study of the Deaf community and deaf institutions as a whole over the study of the individuals who comprise the community and populate the institutions. This paper argues that the inclusion of diverse deaf figures is an essential component to the future of deaf history. However, historians should not lapse in to straight-forward biography in the vein of their eighteenth and nineteenth-century predecessors. They must use these stories purposefully to advance larger discussions about the history of the deaf and of the United States. The Deaf community has never been monolithic, and in order to fully realize ‘deaf’ as a useful category of historical analysis, the definition of which deaf stories are worth telling must broaden. Biography, when coupled with critical historical analysis, can enrich and diversify deaf American historiography. Key Words Deaf history; historiography; disability history; biography; American; identity. THE STORY OF MR. AND MRS. DEAF 110 L'histoire de «M et Mme Sourde »: l'historiographie des personnes Sourdes dans le passé, le présent et l'avenir Résumé Le présent article offre un résumé de l'historiographie de la surdité aux États-Unis, et propose que dans le futur, la recherche bénéficierait d'une synthèse de la biographie historique et d’une analyse critique. -

Total Communication Programs for Deaf Children. Schools Are

DOCUMENT RESUME, ED' 111 119 95 EC 073.374 AUTHOR Moores, Donald F.; And Others TITLE Evaluation of PIOgrams for Hearing Impaired Children: Report of 1973-74. Research Report No. 81. INSTITUTION Minnesota Univ., Minneapolis.'Research,Development, and Demonstration Center in Education ofHandicapped Children. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (DHEW/OE) , Washington, D.C. BUREAU NO BR-332189 PUB DATE Dec 74 GRANT OEG-09-332189-4533(032) NOTE 234p.;*For related informationsee ED 071 239 and 089 525 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$12.05 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Aurally Handicapped;*Deaf; Early Childhood Education; Exceptional Child Research; Expressive Language; *Longitudinal Studies; Oral Communication; *Preschool Education;*Program Effectiveness; Program Evaluation; Receptive Language;. Special Schools IDENTIFIERS- --Total Communication ABSTRACT Presented is the fourth year report ofa 4-year 'longitudinal study comparing effectiveness ofseven preschocl programs for deaf children. Schools are seen to emphasize etheran oral-aural, Rochester (Oral-aural plus fingerspelling), or total communication method of instruction. Included inthe report are a brief review of literature on educationalprograms for the deaf, summaries of earlier yearly reports, descriptionsof the programs and subjects studied, project findings, and appendixes(such as a classroom Observation schedule). Among findingsreported are: that Ss' scores on the Illinois Test of Psycho linguisticAbilities (ITPA, were alhost identical to the scores of normal hearing children;that Ss' scores on the Metropolitan AchievementTests Primer Battery were equal to those of hearing children in reading andwere lower in arithmetic; that scores on a Receptive Communicationscale showed sound alone,to be the least efficient communicationmode (44 percent) rising to 88 percent when speechreading, fingerspelling,aid signs were added; that improved scores on a test for understandingthe printed word (76 percent as compared to 56percent in 1973 and.38 percent in 1972) reflected increasing. -

Poor Print Quality

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 476 841 FL 027 697 AUTHOR Kontra, Miklos TITLE British Aid for Hungarian Deaf Education from a Linguistic Human Rights Point of View. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 9p.; An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Biennial Conference of the Hungarian Society for the Study of English (4th, Budapest, Hungary, January 28-30, 1999). Some parts contain light or broken text. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) Reports Descriptive (141) JOURNAL CIT Hungarian Journal of Applied Linguistics; vl n2 p63-68 2001 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Deafness; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Oral Communication Method; *Sign Language; Speech Communication; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Hungary; United Kingdom ABSTRACT This paper discusses the issue of oral versus sign language in educating people who are deaf, focusing on Hungary, which currently emphasizes oralism and discourages the use of Hungarian Sign Language. Teachers of people who are hearing impaired are trained to use the acoustic channel and view signing as an obstacle to the integration of deaf people into mainstream Hungarian society. A recent news report describes how the British. Council is giving children's books to a Hungarian college for teachers of handicapped students, because the college believes in encouraging hearing impaired students' speaking skills through picture books rather than allowing then to use sign language. One Hungarian researcher writes that the use of Hungarian Sign Language hinders the efficiency of teaching students who are hard of hearing, because they often prefer it to spoken Hungarian. This paper suggests that the research obscures the difference between medically deaf children, who will never learn to hear, and hearing impaired children, who may learn to hear and speak to some extent. -

21. Bibliografía

BIBLIOGRAFÍA1121 A) Material impreso y/o digitalizado Abergel, R. (s. d.): L’enfant sourd et la psychomôtricite. Hommage à Pereire. Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du Certificat de capacité d‘orthophoniste (Memoria no publicada pre- sentada para la obtención del certificado de capacidad de ortofonista. Universidad Louis Pasteur. Facultad de Medicina. Strasbourg). Acquier, Marie-Laure (2000): «Los Tratados en prosa de Antonio López de Vega: aproxima- ción al discurso político en el siglo XVII», Cuadernos de Historia Moderna, n.º 24, 11-31, pp. 85-106. Aftonio, Elio Festo (1961): De metris, en H. Keil (ed.): Grammatici Latini, vol. VI, Hildes- heim, Olms; reimpr de la. 1.ª ed. de Leipzig, 1874, pp. 31-173. Aguado Díaz, A. L. (1995): Historia de las Deficiencias, Madrid, Escuela Libre Editorial (Col. Tesis y Praxis). Aguirre Lora, G. M. E. (dir./1993): Juan Amós Comenio: obra, andanzas, atmosferas en el IV centenario de su nacimiento. (1592-1992), Coyoacán, Centro de Estudios sobre la Universidad. Agulló y Cobo, Mercedes (1992): La imprenta y el comercio de libros en Madrid (siglos XVI- XVIII), Madrid, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Ainscow, M. (2001): Desarrollo de escuelas inclusivas. Ideas propuestas y experiencias para mejorar las instituciones escolares, Madrid, Narcea. Alcuino de York (1851): Grammatica, en Frobenius (ed.): Opera omnia, en J.-P. Migne: Patro- logia Latina, vol. CI, Turnholti, Brepols, reimpr.de la 1.ª ed. de París, 1777, cols. 849-902. Aldea Vaquero, Quintín de (1986): España y Europa en el siglo XVII. Correspondencia de Saavedra Faxardo. 1631-1633, Madrid, CSIC. Alemán, Mateo (1609): Ortografía castellana, México, Jerónimo Balli. -

The Two Hundred Years' War in Deaf Education

THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/146075 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2020-04-15 and may be subject to change. THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS* WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy EEN WETENSCHAPPELIJKE PROEVE OP HET GEBIED VAN DE SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT NIJMEGEN, VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DECANEN IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP 5 DECEMBER 1995 DES NAMIDDAGS TE 3.30 UUR PRECIES DOOR AGNES ELIZABETH JACOBA MARIA TELLINGS GEBOREN OP 9 APRIL 1954 TE ROOSENDAAL Dit onderzoek werd verricht met behulp van subsidie van de voormalige Stichting Pedon, NWO Mediagroep Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen PROMOTOR: Prof.Dr. A.W. van Haaften COPROMOTOR: Dr. G.L.M. Snik 1 PREFACE The methods controversy in deaf education has fascinated me since I visited the International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Hamburg (Germany) in 1980. There I was struck by the intemperate emotions by which the methods controversy is attended. This book is an attempt to understand what this controversy really is about I would like to thank first and foremost Prof.Wouter van Haaften and Dr. -

Deaf History Notes Unit 1.Pdf

Deaf History Notes by Brian Cerney, Ph.D. 2 Deaf History Notes Table of Contents 5 Preface 6 UNIT ONE - The Origins of American Sign Language 8 Section 1: Communication & Language 8 Communication 9 The Four Components of Communication 11 Modes of Expressing and Perceiving Communication 13 Language Versus Communication 14 The Three Language Channels 14 Multiple Language Encoding Systems 15 Identifying Communication as Language – The Case for ASL 16 ASL is Not a Universal Language 18 Section 2: Deaf Education & Language Stability 18 Pedro Ponce DeLeón and Private Education for Deaf Children 19 Abbé de l'Epée and Public Education for Deaf Children 20 Abbé Sicard and Jean Massieu 21 Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet 23 Martha's Vineyard 24 The Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons 27 Unit One Summary & Review Questions 30 Unit One Bibliography & Suggested Readings 32 UNIT TWO - Manualism & the Fight for Self-Empowerment 34 Section 1: Language, Culture & Oppression 34 Language and Culture 35 The Power of Labels 35 Internalized Oppression 37 Section 2: Manualism Versus Oralism 37 The New England Gallaudet Association 37 The American Annals of the Deaf 38 Edward Miner Gallaudet, the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, and the National Deaf-Mute College 39 Alexander Graham Bell and the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf 40 The National Association of the Deaf 42 The International Convention of Instructors of the Deaf in Milan, Italy 44 -

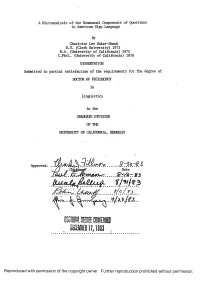

Iffls G E M M E U . IW EB17J8S3

A M icroanalysis o f the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language By Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk B.S. (Clark U niversity) 1972 M.A. O Jniversity o f C alifornia) 1975 C.Phil. (University of California) 1978 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved: Date IfflSGEMMEU . IWEB17J8S3 \ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A Microanalysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language C opyright © 1983 by Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements .................................................................................. v ii List of Figures .................................................................................... x List of Photographs ..................................... x ii List of Drawings .......................................................................................x i i i Transcription Conventions .................................................... iv C hapter I - EXPERIENCES OF DEAF PEOPLE IN A HEARING WORLD ................................................. 1 1.0 Formal education of deaf people: historical review •• 1 1.1 -

The Development of Education for Deaf People

1 Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people The development of education for deaf people Legacy of the Past The book Legacy of the Past (Some aspects of the history of blind educa- tion, deaf education, and deaf-blind education with emphasis on the time before 1900) contains three chapters: Chapter 1: The development of education for blind people Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people Chapter 3: The development of education for deaf-blind people In all 399 pp. An internet edition of the whole book in one single document would be very unhandy. Therefore, I have divided the book into three documents (three inter- netbooks). In all, the three documents contain the whole book. Legacy of the Past. This Internetbook is Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people. Foreword In his Introduction the author expresses very clearly that this book is not The history of blind education, deaf education and deaf-blind education but some aspects of their history of education with emphasis on the time before 1900. Nevertheless - having had the privilege of reading it - my opinion is that this volume must be one of the most extensive on the market today regarding this part of the history of special education. For several years now I have had the great pleasure of working with the author, and I am not surprised by the fact that he really has gone to the basic sources trying to find the right answers and perspectives. Who are they - and in what ways have societies during the centuries faced the problems? By going back to ancient sources like the Bible, the Holy Koran and to Nordic Myths the author gives the reader an exciting perspective; expressed, among other things, by a discussion of terms used through our history. -

The Challenges of Deaf Women in Society: an Investigative Report

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program Spring 2020 The Challenges of Deaf Women in Society: An Investigative Report Megan Harris Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Disability Studies Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Megan, "The Challenges of Deaf Women in Society: An Investigative Report" (2020). Honors Theses. 772. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/772 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SENIOR THESIS APPROVAL This Honors thesis entitled “The Challenges of Deaf Women in Society: an Investigative Report” written by Megan Harris and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion of the Carl Goodson Honors Program meets the criteria for acceptance and has been approved by the undersigned readers. __________________________________ Mrs. Carol Morgan, thesis director __________________________________ Dr. Kevin Motl, second reader __________________________________ Dr. Benjamin Utter, third reader __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, Honors Program director June 5, 2020 THE CHALLENGES OF DEAF WOMEN IN SOCIETY 2 The Challenges of Deaf Women in Society: An Investigative Report Megan Harris Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders Ouachita Baptist University Mrs. Carol Morgan HNRS 4982: Honors Thesis THE CHALLENGES OF DEAF WOMEN IN SOCIETY 3 Abstract History has recorded the mistreatment of both Deaf people and women across time and cultures. The discrimination, struggle for rights, and the strides of progress thus far are congruent themes in both narratives, but neither expressly acknowledges the experiences of Deaf women, who encounter prejudice for both labels. -

The Methods Debate Within Deaf Education in Historical Perspective

Signs versus Whispers: The Methods debate within Deaf Education in Historical Perspective with the Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind (FSDB) as a case study. Melissa Klatzkow Klatzkow 2 Table of Contents: Introduction: 3 Chapter One: Prelude to the oralist movement: 9 Chapter Two: The Changes In Sentiments: 16 Chapter Three: The “Rise” of Oralism: 23 Chapter Four: The Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind; St. Augustine: 33 Epilogue: 51 Conclusion: 57 Glossary: 63 Bibliography: 64 Klatzkow 3 Introduction Mr. and Mrs. Cole were like any couple, living in a typical town at the turn of the century. They lived in an average house and worked normal jobs. They attended church and were, for all intents and purposes, model citizens. Several years into their marriage, they had a daughter they named Susan. At first, the Coles’ were delighted—they had wanted a child for some time now—but soon they began noticing that their daughter was developmentally behind. Mrs. Cole noticed it first. She realized that, where her friend’s babies had begun to babble, her own was silent. At first, she brushed it off and decided to ignore it, but as Susan grew older and no speech became apparent, the Coles’ concern grew. Eventually, they took Susan to a doctor, only to have their worst fears confirmed—Susan was deaf. This shocked the Coles—neither had a deaf relative and Susan had always been very healthy. Their doctor began telling them about how their daughter would enter a residential school, where she would have little contact with them for most of the year.