Anthropological and Other "Ancestors": Notes on Setting up a Visual Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gende*-Bending Anth*Opological

!"#$"%&'"#$(#)*+#,-%./.0.)(120*3,4$("5*.6*7$412,(.# +4,-.%859:*+;<*3,2;=21- 3.4%1":*+#,-%./.0.)<*>*7$412,(.#*?42%,"%0<@*A.0B*CD@*E.B*F*8G"1B@*HIII9@*//B*FFH&FFJ K4=0(5-"$*=<:*'021LM"00*K4=0(5-(#)*.#*="-206*.6*,-"*+;"%(12#*+#,-%./.0.)(120*+55.1(2,(.# 3,2=0"*NOP:*http://www.jstor.org/stable/3196139 +11"55"$:*HQRDQRQDDI*DD:FD Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Anthropology & Education Quarterly. -

Mary Douglas: Purity and Danger

Purity and Danger This remarkable book, which is written in a very graceful, lucid and polemical style, is a symbolic interpretation of the rules of purity and pollution. Mary Douglas shows that to examine what is considered as unclean in any culture is to take a looking-glass approach to the ordered patterning which that culture strives to establish. Such an approach affords a universal understanding of the rules of purity which applies equally to secular and religious life and equally to primitive and modern societies. MARY DOUGLAS Purity and Danger AN ANALYSIS OF THE CONCEPTS OF POLLUTION AND TABOO LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 1966 ARK Edition 1984 ARK PAPERBACKS is an imprint of Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. © 1966 Mary Douglas 1966 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0-415-06608-5 (Print Edition) ISBN 0-203-12938-5 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-17578-6 (Glassbook Format) Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 1. -

Jeremy Boissevain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM An Outsider Looking in: Jeremy Boissevain Rob van Ginkel, University of Amsterdam Irene Stengs, Meertens Institute, Amsterdam Jeremy F. Boissevain (London, 1928) established his name in anthropology as one of the ‘Bs’ – Boissevain, Barth, Bailey, Barnes, Bott –, who in the 1960s and 1970s were important in superseding the structural-functionalist paradigm in Brit- ish social anthropology with an actionist approach. Focusing on choice rather than constraint, on individual agency rather than structure, on manipulation and power-play rather than rules and tradition, and on dyadic relationships and ephemeral groupings rather than corporate groups, these transactional- ists were instrumental in bringing the individual back into the scope of social anthropology. Boissevain’s typology and analysis of quasi-groups (networks, coalitions, factions), ‘man the manipulator’, and phenomena like patronage, factionalism, and local-level politics provided new conceptual and analytic tools to anthropologists, especially those working in Europe. After he was appointed professor at the University of Amsterdam in 1966, it seemed as if he would move on after a couple of years, the reason being that he was unhappy with his outsider position and the local academic climate. But through a series of coincidences, he decided to stay on and to commit himself to developing new vistas for anthropology in Amsterdam. Working in the Netherlands during a period of expansion in the academia, he was able to gather a growing circle of anthropologists around him and to establish Anthropology of Europe as a legitimate subfield there. -

Before and After Gender Hau Books

BEFORE AND AFTER GENDER Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com BEFORE AND AFTER GENDER SEXUAL MYthOLOGIES OF EVERYdaY LifE Marilyn Strathern Edited with an Introduction by Sarah Franklin Afterword by Judith Butler Hau Books Chicago © 2016 Hau Books and Marilyn Strathern Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Cover photo printed with permission from the Barbara Hepsworth Estate and The Art Institute of Chicago: Barbara Hepworth, English, 1903-1975, Two Figures (Menhirs), © 1954/55, Teak and paint, 144.8 x 61 x 44.4 cm (57 x 24 x 17 1/2 in.), Bequest of Solomon B. Smith, 1986.1278 Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-3-7 LCCN: 2016902723 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Distributed Open Access under a Creative Commons License (CC-BY ND-NC 4.0) The Priest Sylvester, in Russia in the sixteenth century, writes to his son: The husband ought to teach his wife with love and sensible punishment. The wife should ask her husband about all matters of decorum; how to save her soul; how to please the husband and God; how to keep the house in good order. And to obey him in every- thing. -

Concept of Tribe and Tribal Community Development

Title of Paper : Administration and Development of Tribal Community Paper Code : DTC405 Year : Second Level : 4th Semester Concept of Tribe and Tribal Community Development The word “Tribe” is taken from the Latin word “Tribus” which means “one third”. The word originally referred to one of the three territorial groups which united to make Rome. India is known as a Melting pot of tribes and races. After Africa India has the second largest concentration of tribal population within the world. Approximately there are about 698 Scheduled Tribes that constitute 8.5% of the India’s population as 2001 censes. Tribal population have some specific characteristics which are different from others tribes. They are simple people with unique customs, traditions and practices. They lived a life of isolation or you can say that geographical isolation. In India aboriginal tribes have lived for 1000 of years in forests and hilly areas without any communication with various centers of civilization. Now, there is a need to integrate tribes in to main stream of the society as a rightful member with respect. Concept and Definition of Tribe: There is no exact definition or the criteria for considering a tribe as a human group. However researchers defined it in various forms at different times. Sometimes they called “Tribe” as “aboriginal” or “depressed classes” or “Adivasees”. Normally, ‘tribe’ may be a group of individuals during a primitive or barbarous stage of development acknowledging the authority of a chief and typically regarding them as having a same ancestor. According to the Imperial Gazetteer of India, a tribe is a collection of families bearing a common name, speaking a common dialect, occupying or professing to occupy a common territory and is not usually endogamous, though originally it might have been so. -

African Critical Inquiry Programme Ivan Karp Doctoral Research Awards

African Critical Inquiry Programme Ivan Karp Doctoral Research Awards Founded in 2012, the African Critical Inquiry Programme (ACIP) is a partnership between the Centre for Humanities Research at University of the Western Cape in Cape Town and the Laney Graduate School of Emory University in Atlanta. Supported by donations to the Ivan Karp and Corinne Kratz Fund, the ACIP fosters thinking and working across public cultural institutions, across disciplines and fields, and across generations. It seeks to advance inquiry and debate about the roles and practice of public culture, public cultural institutions and public scholarship in shaping identities and society in Africa through an annual ACIP workshop and through the Ivan Karp Doctoral Research Awards, which support African doctoral students in the humanities and humanistic social sciences enrolled at South African universities. For further information, see http://www.gs.emory.edu/about/special/acip.html and https://www.facebook.com/ivan.karp.corinne.kratz.fund. Ivan Karp Doctoral Research Awards Each year, ACIP’s Ivan Karp Doctoral Research Awards support African students (regardless of citizenship) who are registered in PhD programs in the humanities and humanistic social sciences in South Africa and conducting dissertation research on relevant topics. Grant amounts vary depending on research plans, with a maximum award of ZAR 40,000. Awards support doctoral projects focused on topics such as institutions of public culture, museums and exhibitions, forms and practices of public scholarship, culture and communication, and theories, histories and systems of thought that shape and illuminate public culture and public scholarship. Projects may work with a range of methodologies, including research in archives and collections, fieldwork, interviews, surveys, and quantitative data collection. -

![Out of Context: the Persuasive Fictions of Anthropology [And Comments and Reply] Author(S): Marilyn Strathern, M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6934/out-of-context-the-persuasive-fictions-of-anthropology-and-comments-and-reply-author-s-marilyn-strathern-m-596934.webp)

Out of Context: the Persuasive Fictions of Anthropology [And Comments and Reply] Author(S): Marilyn Strathern, M

Out of Context: The Persuasive Fictions of Anthropology [and Comments and Reply] Author(s): Marilyn Strathern, M. R. Crick, Richard Fardon, Elvin Hatch, I. C. Jarvie, Rix Pinxten, Paul Rabinow, Elizabeth Tonkin, Stephen A. Tyler and George E. Marcus Source: Current Anthropology, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Jun., 1987), pp. 251-281 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2743236 Accessed: 16-03-2017 13:41 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, The University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Current Anthropology This content downloaded from 164.41.102.240 on Thu, 16 Mar 2017 13:41:13 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY Volume 28, Number 3, June I987 ? I987 by The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. All rights reserved OOII-3204/87/2803-0002$2.5O This is the confession of someone brought up to view Sir James Frazer in a particular way who has discovered that Out of Context the context for that view has shifted. -

“Theory” in Postwar Slovenian Ethnology

Slavec Gradišnik Against the “Aversion to Theory” Against the “Aversion to Theory”: Tracking “Theory” in Postwar Slovenian Ethnology Ingrid Slavec Gradišnik ZRC SAZU, Institute of Slovenian Ethnology Slovenia Abstract As elsewhere in Europe, disciplinary transformations of ethnology and folklore studies in Slo- venia were embedded in the changing political and social map after the Second World War. In the postwar years, sporadic reflections on the discipline’s academic and social position antici- pated the search for a new disciplinary identity. The first attempts to reconceptualize “folk cul- ture” as a building block of ethnological research and the use of the name “ethnology” instead of “ethnography/Volkskunde” in the 1950s also reflected the approaching of “small national ethnology” to “European ethnology.” Only in the 1960s and 1970s, radical epistemological and methodological criticism anticipated the transformation of the disciplinary landscape. The article tracks paradigmatic shifts in the field of tension between empirically oriented and theoretically grounded research. The former regarded “theorizing” as superfluous or the op- posite of “practice.” It more or less reproduced the “salvage project” and the positivist model of cultural-historical and philologically oriented research. The new agenda proposed a dialectical genetic-structural orientation that advocated for a “critical scholarship.” It insisted on the correspondence between the discipline’s subject and the empirical reality that reflects the socio- historical dynamics inherent to culture and everyday life. It introduced “way of life” (everyday life, everyday culture) as a core subject of research that expanded research topics, called for new methodological tools, revised affiliations to related disciplines, recognized discipline’s applied aspects, and addressed the re-reading of disciplinary legacy. -

W. Wilder the Culture of Kinship Studies In: Bijdragen Tot De

W. Wilder The culture of kinship studies In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 129 (1973), no: 1, Leiden, 124-143 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 05:49:08AM via free access REVIEW ARTICLE W. D. WILDER THE CULTURE OF KINSHIP STUDIES Rethinking Kinship and Marriage, edited by Rodney Needham; A.S.A. Monograph 11, Tavistock Publications, London 1971, cxix, 276 pp. £4.00. The Morgan centenary year (1971) saw a larger-than-usual out- pouring of books on kinship and marriage, even though their appearance on this occasion was apparently no more than a coincidence, since in none of them is the centenary date noticed as such.1 More importantly, the reader of these books, with a single exception, confronts merely a restatement or adaptation of older views or the original statements of those views, reprinted. The one exception is the last-published of all these books, Rethinking Kinship and Marriage, presently under review. These facts in themselves may say a great deal about the modern study of kinship fully one hundred years on,2 besides making ASA 11 an essential text for all those anthropologists who are (as Needham once remarked of Hocart) "not much concerned to pander to received ideas".3 1 In addition to Rethinking Kinship and Marriage (ASA 11), there had already appeared in France, the U.S.A. and Britain: L. Dumont Introduction a Deux Thiories d'Anthropologie Sociale: Groupes de Filiation et Alliance de Manage (Mouton, 1971); H. Scheffler and F. -

'Anthropology'?

Anthropology? What ‘Anthropology’? written by Mateusz Laszczkowski January 24, 2019 In September 2018, Jarosław Gowin, Poland’s Minister of Science and Higher 1 of 8 Education, abolished anthropology as an academic discipline by an executive decree. The much-protested new law on higher education entered into force on 1 October 2018. Amid mounting outcry, this post attempts to outline the significance of this decision, identify its practical consequences and situate it against a background of our discipline’s more general crisis. In a famous scene from the 1980s Polish comedy film Miś (‘Teddy Bear’) a man walks into a post office to make a long distance phone call. ‘London?’ the jaded clerk behind the counter replies. Checking the thick register she responds, ‘There’s no such place called “London”. There’s only Lądek, Lądek Zdrój.’ To a Polish ear, Lądek, pronounced ‘Londek’, is phonetically similar to ‘London’. The man patiently explains that he means ‘London, a city in England’, to which the clerk angrily exclaims: ‘Why didn’t you say it’s abroad?! Gotta look it up!’ The scene ridicules the ignorance and parochialism of Polish public institutions in the declining years of ‘real socialism’. But with Minister Jarosław Gowin’s recently introduced academic reform, foreign anthropologists seeking collaboration with their peers in Poland may soon expect to be confronted with a similar response: ‘Anthropology? What anthropology? There’s no such discipline.’ October 1 is the inauguration of the new academic year in Poland. It was on that day that the new law on Higher Education and Science entered into force. -

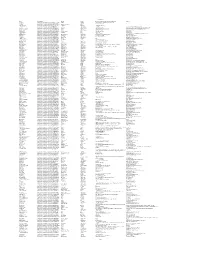

OAC Members Page 1 Name Profile Address Location Country School

OAC Members Name Profile Address Location Country School/Organization/Current anthropological attachment Website Erik Cohen http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_0q3436294e00n Bangkok Thailand Hebrew University of Jerusalem Israel (Emeritus) - Liviu Chelcea http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_13fm1mp3j3ec0 Romania economic anth, kinship - Fiza Ishaq http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_257csvwenh01d Bangalore, Karnataka India -- -- Budi Puspa Priadi http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_2chvjykjv4cz8 Yogyakarta Indonesia Gadjah Mada University ---- E. Paul Durrenberger http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_3l4ha53wqxfjt United States Penn State //www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/e/p/epd2/ Joe Long http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_0b6vedfu8to4e Aberdeen United Kingdom University of Aberdeen /www.abdn.ac.uk/anthropology/postgrad/details.php?id=anp037 Louise de la Gorgendiere http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_1w9frbg5i32ep Ottawa Canada Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada /www.carleton.ca/socanth/faculty/gorgendiere.html Sebnem Ugural http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_0h8qc5txfeu01 london United Kingdom University of Essex /www.seb-nem.com/ millo mamung http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_0cs1x9hd3jmlk arunachal pradesh India rajiv gandhi university @yahoo.com Mangi Lal Purohit http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_0r5sad7imypae Rajasthan India Aakar Trust aakartrust.org Hakan Ergül http://openanthcoop.ning.com/xn/detail/u_2o9ookbjyxvcv Turkey Anadolu University academy.anadolu.edu.tr/xdisplayx.asp?kod=0&acc=hkergul -

Mise En Page 1

c rgo Revue internationale d’anthropologie culturelle & sociale Anne-Marie Dauphin-Tinturier a recueilli de nombreux contes qu’elle a analysés et s’est intéressée à l’initiation des filles dans la région de parler bemba (Zambie) et à ses relations avec le développement. Par ailleurs, elle travaille sur la numérisation de la performance de littérature orale sous forme d’hypermedia. Mots-clés : initiation – Zambie – cibemba – SIDA – développement Du rôle du cisungu dans la région de parler bemba en Zambie Anne-Marie Dauphin-Tinturier LLACAN/CNRS e cisungu , rituel d’initiation des jeunes filles, a été observé et décrit par Audrey Richards dans un livre devenu un classique de l’anthropologie britannique. Dans lLa seconde préface, écrite à l’occasion de la réédition de l’ouvrage en 1982, l’auteur précise que ce que le livre décrit pourrait bien avoir complétement disparu : « This book is therefore a record of what may now be quite extinct » (Richards, 1982 : xIII ). Et, pourtant, en 1989, j’assistais à une partie du rituel final dans la région où, en 1931, Audrey Richards s’était rendue (Chilonga). En 1998, j’observais également une cérémonie finale dans une ville de la Copperbelt (« la ceinture de cuivre »), près de la mine de Nkana, là où, en 1934, elle avait refusé d’aller ( ibid. ). Ainsi, l’initiation des filles n’a pas totalement disparu, mais une analyse comparative de ces trois rituels montre qu’elle a évolué avec le temps tout au long du siècle. La surprise de voir ces rites, réputés être tombés en désuétude, m’a amené à m’interroger sur les modifications qui s’y sont opérées et sur les nouvelles significations dont ils ont été investis, au regard du contexte particulier de la montée de la pandémie de SIDA en Zambie.