Subsistence Use of Fish and Wildlife in Kotzebue, a Northwest Alaska Regional Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Departkent of the Interior United States Geological Survey

DEPARTKENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OCCURRENCES OF TUNGSTEN MINERALS IN ALASKA Compiled by Edward B. Cobb Open-File Report 82-785 1982 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. REFERENCE LIST The following references give data, as of May 1, 1982, on localities where tungsten minerals have been found in Alaska. References are keyed by number to locations shown on the accompanying map. An asterisk (*) preceding a locality name indicates recorded production. Localities 93-161 (in the Tanacross quadrangle) and 183-197 (in the Chignik and Sutwik Island quadrangles) are the sites of samples collected during geochemical investigations that were part of the Alaska Mineral Resource Assessment Program (AMRAP). Tungsten minerals were identified during microscopic study of the nonmagnetic fractions of the heavy-mineral concentrates of samples from these localities. In most instances the report(s) cited for each occurrence is a summary of data in older reports and was compiled since 1975. Most of the summary reports contain lists of the reports used in their compilation. Citations are in standard bibliographic format with the exception that each includes, in parentheses, an abbreviation for the report or map series and the number of the report or map. Abbreviations used are: AOF, State of Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys Open-File Report; B, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin; BMOF, U.S. Bureau of Mines Open-File Report; C, U.S. Geological Survey Circular; MF, U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies Map; OF, U.S. -

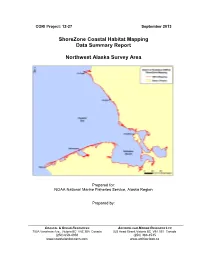

Shorezone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report Northwest

CORI Project: 12-27 September 2013 ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report Northwest Alaska Survey Area Prepared for: NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region Prepared by: COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES ARCHIPELAGO MARINE RESEARCH LTD 759A Vanalman Ave., Victoria BC V8Z 3B8 Canada 525 Head Street, Victoria BC V9A 5S1 Canada (250) 658-4050 (250) 383-4535 www.coastalandoceans.com www.archipelago.ca September 2013 Northwest Alaska Summary (NOAA) 2 SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. The mapping methodology is summarized in Harney et al (2008). This data summary report provides information on geomorphic and biological features of 4,694 km of shoreline mapped for the 2012 survey of Northwest Alaska. The habitat inventory is comprised of 3,469 along-shore segments (units), averaging 1,353 m in length (note that the AK Coast 1:63,360 digital shoreline shows this mapping area encompassing 3,095 km, but mapping data based on better digital shorelines represent the same area with 4,694 km stretching along the coast). Organic/estuary shorelines (such as estuaries) are mapped along 744.4 km (15.9%) of the study area. Bedrock shorelines (Shore Types 1-5) are extremely limited along the shoreline with only 0.2% mapped. Close to half of the shoreline is classified as Tundra (44.3%) with low, vegetated peat the most commonly occurring tundra shore type. Approximately a third (34.1%) of the mapped coastal environment is characterized as sediment-dominated shorelines (Shore Types 21-30). -

National Wildlife Refuge System Koyukukinowitna

U.S. Department of the Interior '·- . Fish and Wildlife Service NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SYSTEM KOYUKUKINOWITNA REFUGE COMPLEX Galena, Alaska ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT Calendar Year 1995 PEC OLL ARR Y/NNWR 395 __gp~ (!.ou_ tJAil. K~ /~tJco' l~ ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT 1995 KOYUKUKNWR NORTHERN UNIT, INNOKO NWR KOYUKUK/NOWITNA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE COMPLEX Galena, Alaska REVIEW AND APPROVALS AJtLIS . US FISH ~ WILDLIFE SERVICE--ALASKA Alaska Resources Lihrary & In f~Jrmation Services Ubraf\' Building. Sml~ Ill 32l i PNwidcnce Onvc 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 }\nchoragc,AJK 99508-t614 3 4982 00022838 6 INTRODUCTION This Annual Narrative Report is for the Koyukuk, Northern Unit of lnnoko and Nowitna Refuges. These three refuges are administered collectively as the Koyukuk/Nowitna Refuge Complex. Narrative items common to all three units are discussed in the Koyukuk and Northern Unit of Innoko report. Any additional events are reported in respective sections. The Koyukuk National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) is located in west central Alaska, about 270 air miles west of Fairbanks and 330 air miles northwest of Anchorage. The exterior boundaries encompass 4.6 million acres. This refuge lies within the roughly circular floodplain basin of the Koyukuk River. The extensive forested floodplain is surrounded by hills 1500' - 4000' to the north, east, and west, and the Yukon River to the south. The Koyukuk NWR was established December 2, 1980 with passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). The refuge was established and is managed for the following purposes: 1. To conserve fish and wildlife populations and habitats in their natural diversity including, but not limited to, waterfowl and other migratory birds, moose, caribou, furbearers and salmon; 2. -

Alex Pumiuqtuuq Whiting — Environmental Director

Alex Pumiuqtuuq Whiting — Environmental Director A view of Kotzebue Sound icing over from the beach at Kotzebue. CONTENTS______________________________________________________________________________ Community of Kotzebue……………..…………………….……………………..……………..….…… Page 3 Geographic Description…………………………..……..………………………………………………. Page 4 Subsistence Resources……………………………….....…………………………...…………………… Page 5 Local and Regional Actors………………………….…………..……….…………………………….… Page 8 Native Village of Kotzebue……………..…………………………..…………………………………… Page 9 Tribal Environmental Program…………………………………………………..………………..…… Page 9 Environmental Document and Management Plan Review……..………………..………...……........ Page 12 City of Kotzebue Cooperative Efforts…………………………...…………….……..………......…… Page 13 State of Alaska Cooperative Efforts…………………………………………………………..….....…. Page 14 Northwest Arctic Borough Cooperative Efforts………………………..……………........…………... Page 16 Federal Government Cooperative Efforts …………………...……..………….………..…..…..…… Page 18 NGO, Alaska Native Organizations & Industry Cooperative Efforts…………………………….… Page 25 Academia Cooperative Efforts……………………………………………………..…...……..….....… Page 28 Education, Communication and Outreach............................................................................. Page 33 Tribal Environmental Program Priorities including Capacity Building ....................................Page 34 Appendix 1: Native Village of Kotzebue Research Protocol & Questionnaire….………………..… Page 37 Appendix 2: NEPA/Management Plans - Review and Comment…………………………………..Page -

Background Section

NORTHWEST ARCTIC SUBAREA CONTINGENCY PLAN BACKGROUND SECTION BACKGROUND: PART ONE – SUPPORT INFORMATION ............................................................................. E‐1 A. SUBAREA PLAN ................................................................................................................................... E‐1 B. SUBAREA DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................................... E‐1 C. AREA OF RESPONSIBILITY .................................................................................................................. E‐6 D. REGIONAL STAKEHOLDER COMMITTEE ............................................................................................. E‐7 E. SUBAREA COMMITTEE ....................................................................................................................... E‐9 BACKGROUND: PART TWO – RESPONSE POLICY & STRATEGIES ............................................................. E‐11 A. FEDERAL RESPONSE ACTION PRIORITIES/STRATEGIES .................................................................... E‐11 B. STATE OF ALASKA RESPONSE PRIORITIES ........................................................................................ E‐12 BACKGROUND: PART THREE ‐ SUBAREA SPILL HISTORY, OIL FATE & RISK ASSESSMENT ......................... E‐13 A. NAVIGABLE WATERS SPILL HISTORY ................................................................................................ E‐13 B. INLAND SPILL HISTORY .................................................................................................................... -

Late Precontact Settlement on the Northern Seward Peninsula Coast: Results of Recent Fieldwork

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2017 Late Precontact Settlement on the Northern Seward Peninsula Coast: Results of Recent Fieldwork Shelby L. Anderson Portland State University, [email protected] Justin Andrew Junge Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Anderson, Shelby L. and Junge, Justin Andrew, "Late Precontact Settlement on the Northern Seward Peninsula Coast: Results of Recent Fieldwork" (2017). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 132. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/132 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. LATE PRE-CONTACT SETTLEMENT ON THE NORTHERN SEWARD PENINSULA COAST: RESULTS OF RECENT FIELDWORK Shelby L. Anderson Portland State University, PO Box 751, Portland, OR; [email protected] Justin A. Junge Portland State University, PO Box 751, Portland, OR; [email protected] ABSTRACT Changing arctic settlement patterns are associated with shifts in socioeconomic organization and interaction at both the inter- and intra-regional levels; analysis of Arctic settlement patterns can inform research on the emergence and spread of Arctic maritime adaptations. Changes in late pre-contact settlement patterns in northwest Alaska suggest significant shifts in subsistence and/or social organization, but the patterns themselves are not well understood. -

İnyupikçe Bitki Ve Hayvan Adları ÜMÜT ÇINAR Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names

İnyupikçe Bitki ve Hayvan Adları Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names Niġrutillu Nautchiallu I (Mammals & Birds) ✎ Ümüt Çınar Nisan 2017 KEÇİÖREN / ANKARA Turkey Kmoksy www.kmoksy.com www.kmoksy.com Sayfa 1 İnyupikçe Bitki ve Hayvan Adları ÜMÜT ÇINAR Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names The re-designed images or collages (mostly taken from the Wikipedia) are not copyrighted and may be freely used for any purpose Iñupiaq (ipk = esi & esk)-speaking Area www.kmoksy.com Sayfa 2 İnyupikçe Bitki ve Hayvan Adları ÜMÜT ÇINAR Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names Eskimo-Aleut dilleri içinde İnyupikçenin konumu Eskimo - Aleut dilleri 1. Eskimo - Aleut languages Aleutça (Unanganca) 1.1. Aleut (Unangan) Eskimo dilleri 1.2. Eskimo languages Yupik dilleri 1.2.1. Yupik languages Sirenik Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1. Sireniki language Öz Yupik dilleri 1.2.1.1. Yupik proper Sibirya Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.1. Siberian Yupik Naukan Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.2. Naukan Yupik Alaska Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. Central Alaskan Yup'ik Unaliq-Pastuliq Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. 1. Norton Sound Yup'ik Yupikçe 1.2.1.1.3. 2. Yukon and Kuskokwin Yup'ik Egegik Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. 3. Bristol Bay Yup'ik Çupikçe 1.2.1.1.3. 4. Hooper Bay and Chevak Cup'ik Nunivak Çupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. 5. Nunivak Cup'ig Supikçe 1.2.1.1.4. Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) İnuit dilleri 1.2.2. Inuit languages İnyupikçe 1.2.2.1. Inupiaq Batı Kanada İnuitçesi 1.2.2.2. Western Canadian Inuit (Inuvialuktun) Doğu Kanada İnuitçesi 1.2.2.3. -

TERRITOHP of Klasha No. 5

TERRITOHP OF kLASHA DEPARTMENT OF 1vIINES 3; D. Stewart, Commissioner of Mines Ppphlet6 ' No. 5 MINERAL OC-CES IN NORlXWE5TERN WKA BY ESKIL ANDERSON Juneau, Alaska us, 1944- Page Introduction .......................................... 1 Antimony .............................................. 3 Cape Nome precinct ............................... 3 Cape Nome district .......................... 3 Council district. ........................... 5 Kougarok district ........................... 5 Port Clarence district ...................... 5 St . Tdichael precinct ............................. 6 Asbestos .............................................. 6 Cape Nome precinct ............................... 6 Port Clarence district ...................... 6 Fairhaven precinct ............................... 6 Koyuk precinct ................................... 7 Noatak-Kobuk precinct ............................ 7 Bexyllim......................................... 9 Cape Nome precinct......^........................ 9 Bimth............................................... 9 Gape Name precinct ............................... 9 Cape Nome district .......................... 9 Port Clarence district ....................... 9 St. bfichael precinct ............................. 10 ChoLZ1Jw .............................................. 10 Koyuk preoinct ................................... 10 Noatak-Kobuk precinct ............................ 10 Copper ............................................... 10 Cap Nome precinct ............................... 10 Cape -

Kotzebue Sound Physical Oceanography: 2015 Study of Currents, Temperature & Salinity

Kotzebue Sound Physical Oceanography: 2015 Study of Currents, Temperature & Salinity Study Findings: • Kotzebue Sound water temperatures and salinities change quickly during and after breakup, adjusting to the influence of river discharge and solar heating. • Tides, winds, and changes in temperature or salinity are responsible for ocean currents in Kotzebue Sound. The importance of each varies in time and place. • The 12-hour tidal currents are stronger than the 24-hour tidal currents and are largest near Cape Espenberg. • The southern Kotzebue Sound shoreline appears to be at greater risk from beaching of oil and other ocean-borne contaminants than other portions of the sound. • Marine water temperatures in June 2015 were warm enough to support blooms of toxic algae in Kotzebue Sound. • A clockwise gyre flow can develop in the southwestern (Goodhope Bay) portion of Kotzebue Sound. • Kotzebue Sound is upstream both of Kivalina and Point Hope. Wind from the southeast and fresh river water helps drive currents out of the south to the north past Cape Kruzenstern and Kivalina. Deployment of a satellite-tracked drifter Behind the science: This study collected water speed, direction and temperature data using satellite-tracked oceanographic drifters (photo above) that move with ocean currents and report their location and the sea surface temperature each hour. We also collected water temperature and salinity data using hand-lowered conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) instruments and we examined satellite images (examples below) to follow the evolution of the spring river and ice breakup. Satellite images from 19 May 2015 (left) and 31 May 2015 (right) showing the rapid progression of ice breakup and the delivery of sediment-laden river waters to the coast. -

Northwestern Alaska Dolly Varden and Arctic Char

Fishery Management Report No. 09-48 Fishery Management Report for Sport Fisheries in the Northwest/North Slope Management Area, 2008 by Brendan Scanlon December 2009 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye to fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye to tail fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright © common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co. -

Department of Agriculture Department of the Interior

Wednesday, June 30, 2010 Part III Department of Agriculture Forest Service 36 CFR Part 242 Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 100 Subsistence Management Regulations for Public Lands in Alaska—2010–11 and 2011–12 Subsistence Taking of Wildlife Regulations; Subsistence Taking of Fish on the Yukon River Regulations; Final Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 18:11 Jun 29, 2010 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\30JNR2.SGM 30JNR2 emcdonald on DSK2BSOYB1PROD with RULES2 37918 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 125 / Wednesday, June 30, 2010 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 1011 East Tudor Road, Mail Stop 121, • Alaska Regional Director, U.S. Fish Anchorage, Alaska 99503, or on the and Wildlife Service; Forest Service Office of Subsistence Management Web • Alaska Regional Director, U.S. site (http://alaska.fws.gov/asm/ National Park Service; 36 CFR Part 242 index.cfml). • Alaska State Director, U.S. Bureau FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of Land Management; DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Chair, Federal Subsistence Board, c/o • Alaska Regional Director, U.S. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs; and Fish and Wildlife Service Attention: Peter J. Probasco, Office of • Alaska Regional Forester, U.S. Subsistence Management; (907) 786– Forest Service. 50 CFR Part 100 3888 or [email protected]. For Through the Board, these agencies [Docket No. FWS–R7–SM–2009–0001; questions specific to National Forest participate in the development of 70101–1261–0000L6] System lands, contact Steve Kessler, regulations for subparts A, B, and C, Subsistence Program Leader, USDA, RIN 1018–AW30 which set forth the basic program, and Forest Service, Alaska Region, (907) they continue to work together on Subsistence Management Regulations 743–9461 or [email protected]. -

Imuruk Lake Quartz Creek

T 165°0'0"W 164°0'0"W 163°0'0"W 162°0'0"W Clifford Creek Rex Creek SImnmitha cChrueke kRiver Deering I Goodnews Bay Sullivan Creek Cripple River Sullivan Bluffs Deering Ninemile Point Alder Creek Francis Creek Sullivan Lake Grayling Creek Reindeer Creek Hunter Creek Willow Bay Kirk Creek Kiwalik CamWpill oCwre Cekreek Kugruk Lagoon Minnehaha Creek Lone Butte Creek Eagle Creek Virginia Creek Kugruk River 66°0'0"N Iowa Creek Kiwalik Lagoon Pot Creek Inmachuk River Lava Creek Richmond Creek Wabash Creek A 66°0'0"N May Creek Mud Channel Creek Iron Creek Mystic Creek Middle Channel Kiwalk River Humbolt Creek North Channel Kiwalk River Cue Creek Mud Creek Moonlight Creek Mud Creek Ditch Kiwalik River West Creek Washington Creek Oregon Creek Snowshoe Creek Hoodlum Creek Polar Bear Creek California Creek Snow Creek CandleCandle Candle Creek Hot Springs CreekSchlitz Creek Cunningham CreekMilroy Creek Mystery Creek Jump Creek Portage Creek R Bryan Creek Ballarat Creek Fink Creek Contact Creek Teller Creek Inmmachuck River Chicago Creek Collins Creek Chicago Creek Fink Creek Limestone Creek Arizona Creek Burnt River Diamond Creek Foster, Mount Logan Gulch Hannum Creek Pinnell River Short Creek Grouse Creek Mukluk Creek Eureka CreekEureka Gulch First Chance Creek Willow Creek Old Glory Creek Reindeer Creek Lincoln Creek Rain Gulch Serpentine Hot Springs Wallin Coal Mine Camp 19 Patterson Creek Snow Gulch Fox Creek Nelson Creek Dacy Gulch T American Creek Lava Creek Bella Creek Little Daisy Creek Goldbug Creek Blank Creek Dick Creek Reindeer Creek