Immediation I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Manning What Things Do When They Shape Each Other

Erin Manning WHAT THINGS DO WHEN THEY SHAPE EACH OTHER The Way of the Anarchive In order to discover some of the major categories under which we can classify the infinitely various components of experience, we must appeal to evidence relating to every variety of occasion. Nothing can be omitted, experience drunk and experience sober, experience sleeping and experience waking, experience drowsy and experience wide-awake, experience self- conscious and experience self-forgetful, experience intellectual and experience physical; experience religious and experience sceptical, experience anxious and experience care-free, experience anticipatory and experience retrospective, experience happy and experience grieving, experience dominated by emotion and experience under self-restraint, experience in the light and experience in the dark, experience normal and experience abnormal (Whitehead 1967: 222) Bolder adventure is needed - the adventure of ideas, and the adventure of practice conforming itself to ideas (Whitehead 1967: 259) 1. METHOD "Every method is a happy simplification," writes Whitehead (1967: 221). The thing is, all accounting of experience travels through simplification - every conscious thought, but also, in a more minor sense, every tending toward a capture of attention, every gesture subtracted from the infinity of potential. And so a double-bind presents itself for those of us moved by the force of potential, of the processual, of the in-act. How to reconcile the freshness, as Whitehead might say, of processes underway with the weight of experience captured? How to reconcile force and form? This was the challenge SenseLab (www.senselab.ca) gave itself when we decided, a few years ago, to develop a concept we call "the anarchive." For us, the concept was initially an attempt to reconsider the role documentation plays in the context of the event. -

Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience Pdf Free

THOUGHT IN THE ACT: PASSAGES IN THE ECOLOGY OF EXPERIENCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erin Manning,Brian Massumi | 224 pages | 01 May 2014 | University of Minnesota Press | 9780816679676 | English | Minnesota, United States Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience PDF Book Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Sign in. Greg marked it as to-read Jan 19, To paint: a thinking through color. Lisa Banu rated it it was amazing Dec 18, N Filbert rated it it was amazing Sep 09, Manning and Massumi, however, depart from the vast scope of their predecessors, limiting their sources to a narrow range, predominantly William James and Alfred North Whitehead, engaged as much for their poetics as for their ideas. Explores the intimate connections between thinking and creative practice. The result is a thinking-with and a writing-in-collaboration-with these processes and a demonstration of how philosophy co-composes with the act in the making. This book feels very timely. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Average rating 4. Kate rated it really liked it Aug 09, Daniella rated it it was amazing Feb 04, We have a verbal travel through the experience of receiving their work, experiencing their re-configuration of spaces and intervention into the physicality of our lives. Keywords: philosophy of art , process philosophy , art and activism , political philosophy , neurodiversity , embodied cognition , art-based research. Drawing from the idiosyncratic vocabularies of each creative practice, and building on the vocabulary of process philosophy, the book reactivates rather than merely describes the artistic processes it examines. Search Site only in current section. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Erin Manning I. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION .....................................................................................................................................3 AC A DEMIC BA CKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................................3 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY ................................................................................................................................................................3 AW A RDS .....................................................................................................................................................................................3 LA NGU A GES ................................................................................................................................................................................4 II. RESEARCH ...........................................................................................................................................................................4 EX H I B ITIONS /PERFORM A NCES (SOLO ) ............................................................................................................................................4 PERFORM A NCES (SOLO ) ...............................................................................................................................................................4 PU B LIC A TIONS (PRINT OR ELECTRONIC ) ..........................................................................................................................................5 -

Homeland Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HOMELAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Fernando Aramburu | 640 pages | 02 Apr 2020 | Pan MacMillan | 9781509858040 | English | London, United Kingdom Homeland PDF Book At eight seasons long, Homeland is already Showtime's second-longest running drama behind Shameless , which premiered nine months before Homeland. Watch on Prime Video included with Prime. With the help of her long-time mentor Saul Berenson Mandy Patinkin , Carrie fearlessly risks everything, including her personal well-being and even sanity, at every turn. Laura Played by Sarah Sokolovic A bright American journalist who works for the same organization as Carrie in Berlin, Laura ends up on the receiving end of some highly classified leaked information that has the potential to devastate U. Trivia Graffiti artists employed to create slogans for a refugee camp in season five actually wrote anti-Homeland slogans such as "Homeland is a joke, and it didn't make us laugh" on the set in protest at the show's portrayal of Muslims. Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon, along with an excellent team of writers, producers, and directors the latter of which was led by the great Lesli Linka Glatter , refused to provide solutions to problems without any. The entire last season, and certainly, the last episode, was geared for those people that have been with the show. The mastermind of an attack on the American Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan that killed 36 Americans, Haqqani is now the head of the Taliban. Wolf was in the chief role at the department in an acting capacity for 14 months. I mean, it was just beyond emotional. -

On Touch, Synaesthesia and Other Ways of Knowing Erin Manning

Not at a Distance : On Touch, Synaesthesia and Other Ways of Knowing Erin Manning A thousand other things sing to me. John Lee Clark Every possible feeling produces a movement, and that movement is a movement of the entire organism, and of each of its parts. William James What if mirror-touch synaesthesia, defined as the expe- rience that ensues when the stimulation of one sensory modality (vision) automatically triggers a perception in a second modality (touch), in the absence of any direct stimulation to this second modality, were not only mis- named, but radically misunderstood? It’s not just the nomenclature that I am concerned with here – why a synaesthesia that is said to move between touch and vision isn’t called vision-touch synaesthesia like its sis- ters, sound-taste, colour-grapheme, shape-taste – but the very presupposition that grounds an account of sensation 148 Erin Manning that can be parsed so cleanly between sense modalities and between the bodies that are said to be the locations of sense. For even if it were called vision-touch synaesthesia, it would still take for granted a whole set of beliefs about both how we perceive and what is considered worthy of being perceived: despite a rare admission that for some the experience of being touched-without-touch occurs through an object,1 mirror-touch synaesthesia is pre- dominantly a humanist concept. To be touched by that which we see is, in most of the literature, to be touched by the human. This is the question I want to ask here: what is assumed in the presupposition that to be moved is to be moved by the human? And what is assumed when we take vision as the predominant activator of the expe- rience of being touched by the world? Circling around autistic perception and DeafBlindness, I want to ask how neurotypicality as the normative standard for human experience operates in the presuppositions of sense. -

Immediation II

Immediation II Edited by Erin Manning, Anna Munster, Bodil Marie Stavning Thomsen Immediation II Immediations Series Editor: SenseLab “Philosophy begins in wonder. And, at the end, when philosophic thought has done its best, the wonder remains” – A.N. Whitehead The aim of the Immediations book series is to prolong the wonder sustaining philosophic thought into transdisciplinary encounters. Its premise is that concepts are for the enacting: they must be experienced. Thought is lived, else it expires. It is most intensely lived at the crossroads of practices, and in the in-between of individuals and their singular endeavors: enlivened in the weave of a relational fabric. Co-composition. “The smile spreads over the face, as the face fits itself onto the smile” – A. N. Whitehead Which practices enter into co-composition will be left an open question, to be answered by the Series authors. Art practice, aesthetic theory, political theory, movement practice, media theory, maker culture, science studies, architecture, philosophy … the range is free. We invite you to roam it. Immediation II Edited by Erin Manning, Anna Munster, Bodil Marie Stavning Thomsen OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS London 2019 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2019. Copyright © 2019, Erin Manning, Anna Munster, Bodil Marie Stavning Thomsen. Chapters copyright their respective authors unless otherwise noted. This is an open access book, licensed under Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy their work so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

2018-2019 CISSC Year in Review

CISSC Year in Review 2018–2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture 3 Letter from the Director 5 CISSC Happenings 7 Public Lectures 7 Workshops and Conferences 12 CISSC Working Groups 14 Ethnocultural Art Histories Research in Media (EAHR) African Studies Material Religion Initiative (MRI) Narrating Childhood The Ethnography Lab Feminism and Controversial Humour CISSC Diversity Research Travel Stipend Report 21 Visiting Scholars 23 Derek Maus Rachel Zellars Natalie Loveless 24 Humanities Interdisciplinary Ph.D Program 26 2018-19 HUMA PhD Graduates Fall 2018 Incoming HUMA PhD Students 27 HUMA Course Descriptions 29 HUMA Graduate Student Activities and Accolades 31 Front cover: Magdalena Hutter, Strudeltuch, 2019 100x140 cm, cotton, polyester thread, flour Back cover: “Résonances manifestes” (Research-creation project by HUMA student Hubert Gendron-Blais) Photo taken by: Gyslain Gaudet ABOUT THE CENTRE The Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture (CISSC), founded in 2007, is a joint creation of the Faculty of Fine Arts and the Faculty of Arts and Science. It ## houses the Humanities Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program (HUMA) which was established in 1973. David Howes is the current director of CISSC. He is also a Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Erin Manning is the current director of HUMA. She is also a dually appointed Professor in Studio Arts and Film Studies. Ana Ramos is the Coordinator of the HUMA program. Tristana Martin Rubio took over from Skye Maule-O’Brien as the Coordinator of CISSC in January 2019. 3 Members of the CISSC Board and PhD Humanities Committee for 2018-2019. -

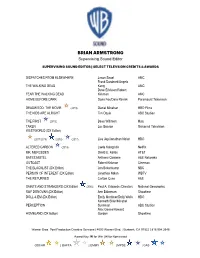

BRIAN ARMSTRONG Supervising Sound Editor

BRIAN ARMSTRONG Supervising Sound Editor SUPERVISING SOUND EDITOR | SELECT TELEVSION CREDITS & AWARDS DISPATCHES FROM ELSEWHERE Jason Segel AMC Frank Darabont/Angela THE WALKING DEAD Kang AMC Dave Erickson/Robert FEAR THE WALKING DEAD Kirkman AMC HOME BEFORE DARK Dana Fox/Dara Resnik Paramount Television DEADWOOD: THE MOVIE (2019) Daniel Minehan HBO Films THE KIDS ARE ALRIGHT Tim Doyle ABC Studios THE FIRST (2019) Beau Willimon Hulu TAKEN Luc Besson Universal Television WESTWORLD (DX Editor) (2017/2018) (2019) (2017) Lisa Joy/Jonathan Nolan HBO ALTERED CARBON (2019) Laeta Kalogridis Netflix MR. MERCEDES David E. Kelley AT&T BATES MOTEL Anthony Cipriano A&E Networks OUTCAST Robert Kirkman Cinemax THE BLACKLIST (DX Editor) Jon Bokenkamp NBC PERSON OF INTEREST (DX Editor) Jonathan Nolan WBTV THE RETURNED Carlton Cuse A&E SAINTS AND STRANGERS (DX Editor) (2016) Paul A. Edwards (Director) National Geographic RAY DONOVAN (DX Editor) Ann Biderman Showtime DOLL & EM (DX Editor) Emily Mortimer/Dolly Wells HBO Kenneth Biller/Micahel PERCEPTION Sussman ABC Studios Alex Gansa/Howard HOMELAND (DX Editor) Gordon Showtime Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.2646 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS SOUND EDITOR | SELECT FEATURE CREDITS THE PURGE (SSE) James DeMonaco Universal Pictures THE INTERN (Supervising Foley Editor) Nancy Meyers Warner Bros. PITCH PERFECT (Sound Editor) Jason Moore Universal Pictures SNITCH (Addl Re-Recording) Ric Roman Waugh Summit Entertainment GET THE GRINGO (Sound FX Editor) Adrian Grunberg Fox THE MUPPETS (Sound Editor) James Bobbin Walt Disney Pictures 30 MINUTES OR LESS (Sound FX Editor) Ruben Fleischer Columbia Pictures HOW DO YOU KNOW (Foley Editor) James L. -

Applying a Rhizomatic Lens to Television Genres

A THOUSAND TV SHOWS: APPLYING A RHIZOMATIC LENS TO TELEVISION GENRES _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by NETTIE BROCK Dr. Ben Warner, Dissertation Supervisor May 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the Dissertation entitled A Thousand TV Shows: Applying A Rhizomatic Lens To Television Genres presented by Nettie Brock A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________________________ Ben Warner ________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz ________________________________________________________ Stephen Klien ________________________________________________________ Cristina Mislan ________________________________________________________ Julie Elman ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Someone recently asked me what High School Nettie would think about having written a 300+ page document about television shows. I responded quite honestly: “High School Nettie wouldn’t have been surprised. She knew where we were heading.” She absolutely did. I have always been pretty sure I would end up with an advanced degree and I have always known what that would involve. The only question was one of how I was going to get here, but my favorite thing has always been watching television and movies. Once I learned that a job existed where I could watch television and, more or less, get paid for it, I threw myself wholeheartedly into pursuing that job. I get to watch television and talk to other people about it. That’s simply heaven for me. A lot of people helped me get here. -

Nomination Press Release

Outstanding Comedy Series 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Productions, Inc. in association with Warner Tina Fey as Liz Lemon Bros. Television Veep • HBO • Dundee Productions in Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO association with HBO Entertainment Entertainment Julia Louis-Dreyfus as Selina Meyer Girls • HBO • Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner Productions in association with HBO Entertainment Outstanding Lead Actor In A Modern Family • ABC • Levitan-Lloyd Comedy Series Productions in association with Twentieth The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Century Fox Television Productions, Inc. in association with Warner 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Bros. Television Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Jim Parsons as Sheldon Cooper Television Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO Veep • HBO • Dundee Productions in Entertainment association with HBO Entertainment Larry David as Himself House Of Lies • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Crescendo Productions, Totally Outstanding Lead Actress In A Commercial Films, Refugee Productions, Comedy Series Matthew Carnahan Circus Products Don Cheadle as Marty Kaan Girls • HBO • Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner Productions in association with Louie • FX Networks • Pig Newton, Inc. in HBO Entertainment association with FX Productions Lena Dunham as Hannah Horvath Louis C.K. as Louie Mike & Molly • CBS • Bonanza Productions, 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Inc. in association with Chuck Lorre Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Productions, Inc. and Warner Bros. Television Television Alec Baldwin as Jack Donaghy Melissa McCarthy as Molly Flynn Two And A Half Men • CBS • Chuck Lorre New Girl • FOX • Chernin Entertainment in Productions Inc., The Tannenbaum Company association with Twentieth Century Fox in association with Warner Bros.