State Archives of Assyria Volume Xix Publications Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thiele's Biblical Chronology As a Corrective for Extrabiblical Dates

Andm University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1996, Vol. 34, No. 2,295-317. Copyright 1996 by Andrews University Press.. THIELE'S BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY AS A CORRECTIVE FOR EXTRABIBLICAL DATES KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University The outstanding work of Edwin R. Thiele in producing a coherent and internally consistent chronology for the period of the Hebrew Divided Monarchy is well known. By ascertaining and applying the principles and procedures used by the Hebrew scribes in recording the lengths of reign and synchronisms given in the OT books of Kings and Chronicles for the kings of Israel and Judah, he was able to demonstrate the accuracy of these biblical data. What has generally not been given due notice is the effect that Thiele's clarification of the Hebrew chronology of this period of history has had in furnishing a corrective for various dates in ancient Assyrian and Babylonian history. It is the purpose of this essay to look at several such dates.' 1. i%e Basic Question In a recent article in AUSS, Leslie McFall, who along with many other scholars has shown favor for Thiele's chronology, notes five vital variable factors which Thiele recognized, and then he sets forth the following opinion: In view of the complex interaction of several of the independent factors, it is clear that such factors could never have been discovered (or uncovered) if it had not been for extrabiblical evidence which established certain key absolute dates for events in Israel and Judah, such as 853, 841, 723, 701, 605, 597, and 586 B.C. It was as a result of trial and error in fitting the biblical data around these absolute dates that previous chronologists (and more recently Thiele) brought to light the factors outlined above.= '~lthou~hmuch of the information provided in this article can be found in Thiele's own published works, the presentation given here gathers it, together with certain other data, into a context and with a perspective not hitherto considered, so far as I have been able to determine. -

Sea-L 3 Jeverling Materials Vol1.Pdf

SPECIMINA ELECTRONICA ANTIQUITATIS – LIBRI 3. 2013 ₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪ ISBN 978-963-642-508-1 Materials for the Study of First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts Volume 1. Chronological List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia János Everling Pécs 2000 Matrials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts vol. 1. Chronological List 1. Introduction Since the publication of the Chronological List of the Ur III texts 1 the attention of several scholars were drawn to the lack of information in the same field concerning the First Millennium B.C. The first attempt to complete our knowledge concerning this period were realized by M. Dandamayev2. Next year R. Zadok published a comprehensive study on the geographical repartition of the material3. Several studies were elaborated for the reconstruction of the first millennium B.C. Babylonian chronology4. The first volume of the “Materials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts” is intended to present the material in chronological order. It was completed in September 2000. The “Materials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts” is a series of volumes whose logical structure can be described as follows: 1. Chronological List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 2. Geographical List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 3. Personal Names of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 4. Thematic Selections from the Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 5. Publication of Text Editions of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. -

1. the Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1982, Vol. 20, No. 3, 229-217. Copyright 0 1982 by Andrews University Press. DARIUS THE MEDE: AN UPDATE WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University The two main historical problems which confront us in the sixth chapter of Daniel have to do with the two main historical figures in it, Darius the Mede, who was made king of Babylon, and Daniel, whom he appointed as principal governor there. The problem with Darius is that no ruler of Babylon is known from our historical sources by this name prior to the time of Darius I of Persia (522-486 B.c.). The problem with Daniel is that no governor of Babylon is known by that name, or by his Babylonian name, early in the Persian period. Daniel's position mentioned here, which has received little attention, will be discussed in a sub- sequent study. In the present article I shall treat the question of the identification of Darius the Mede, a matter which has received considerable attention, with a number of proposals having been advanced as to his identity. I shall endeavor to bring some clarity to the picture through a review of the cuneiform evidence and a comparison of that evidence with the biblical data. As a back- ground, it will be useful also to have a brief overview of the various theories that have already been advanced. 1. The Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede Before we consider the theories regarding the identification of Darius the Mede, however, note should be taken of the information about him that is available from the book of Daniel. -

Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION JOHN ALBERT WILSON & THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN - EDITORS ELIZABETH B. HAUSER & RUTH S. BROOKENS • ASSISTANT EDITORS oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.G.-A.D. 45 oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS - CHICAGO THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY • NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS • LONDON oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.C.-A.D. 45 BT RICHARD A. PARKER AND WALDO H. DUB B ERSTE IX THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • NO. 24 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS . CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu COPYRIGHT 1942 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 1942. COMPOSED AND PRINTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE This study aims at providing a brief, but complete and thorough, presenta tion of the data bearing upon the chronological problems of the Neo-Baby- lonian, Achaemenid Persian, and Seleucid periods, together with tables for the easy translation of dates from the Babylonian calendar into the Julian. Recent additions to our knowledge of intercalary months in the Neo-Baby- lonian and Persian periods have enabled us to improve upon the results of our predecessors in this field, though our great debt to F. X. Kugler and D. Sider- sky for providing the background of our work is obvious. While our tables are intended primarily for historians, both classical and oriental, biblical students also should find them useful, as any biblical date of this period given in the Babylonian calendar can be translated by our tables. -

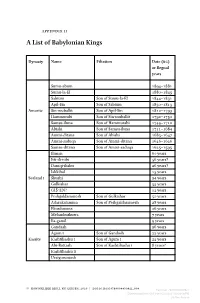

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

IV. a Re-Examination of the Nabonid~S Chonicle I

AN UNRECOGNIZED VASSAL KING OF BABYLON IN THE EARLY ACHAEMENID PERIOD WILLIAM H. SHEA Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, West Indies IV. A Re-examination of the Nabonid~sChonicle I. Comparative Materials Introd~ction.If a solution to the problem posed by the titulary of Cyrus in the economic texts is to be sought, perhaps it is not unexpected that the answer might be found in the Nabonidus Chronicle, since that text is the most specific historical document known that details the events of the time in question. However, there are several places in this re- consideration of the Nabonidus Chronicle where the practices of the Babylonian scribes who wrote the chronicle texts are examined, and for this reason other chronicle texts besides the Nabonidus Chronicle are referred to in this section. The texts that have been selected for such comparative purposes chronicle events from the two centuries preceding the time of the Nabonidus Chronicle. Coincidentally, the chronicle texts considered here begin with records from the reign of Nabonas- sar in the middle of the 8th century B.c., the same time when the royal titulary in the economic texts began to show the changes discussed in the earlier part of this study. Although there are gaps in the information available from the chronicles for these two centuries, we are fortunate to have ten texts that chronicle almost one-half of the regnal years from the time of Nabonassar to the time of Cyrus (745-539). The texts utilized in this study of the chronicles are listed in Table V. * The first two parts of this article were published in A USS, IX (1971), 51-67, 99-128. -

Cyrus the Great, Exiles and Foreign Gods a Comparison of Assyrian and Persian Policies on Subject Nations1

Cyrus the Great, Exiles and Foreign Gods A Comparison of Assyrian and Persian Policies on Subject Nations1 To be published in: Wouter Henkelman, Charles Jones, Michael Kozuh and Christopher Woods (eds.), Extraction and Control: Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper. Oriental Institute Publications. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. R.J. van der Spek VU University Amsterdam Introduction Cyrus, king of Persia (559-530 BC), conqueror of Babylon (539), has a good reputation, also among modern historians. Most textbooks, monographs, and articles on ancient history stress his tolerance towards the countries and nations he subdued. It is mentioned time and again that he allowed them freedom of religion, that he behaved respectfully towards Babylon and its temple cults, and that he reinstated several cults, especially that of the god of Israel in Jerusalem. This policy is often contrasted with that of the Assyrian kings, who are presented as cruel rulers, oppressing subdued nations, destroying sanctuaries, deporting gods and people, and forcing their subjects to worship Assyrian gods. Cyrus’ acts supposedly inaugurated a new policy, aimed at winning the subject nations for the Persian Empire by tolerance and clemency. It was exceptional that Cambyses and Xerxes abandoned this policy in Egypt and Babylonia. In the prestigious Cambridge Ancient History volume on Persia, T. Cuyler Young maintains that Cyrus’ policy “was one of remarkable tolerance based on a respect for individual people, ethnic groups, other religions and ancient kingdoms.” 2 1 This contribution is an update of my article “Cyrus de Pers in Assyrisch perspectief: Een vergelijking tussen de Assyrische en Perzische politiek ten opzichte van onderworpen volken,” Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 96 (1983): 1-27 (in Dutch, for a general audience of historians). -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 06:11:41PM Via Free Access 208 Appendix III

Appendix III The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117 1 Shamshi-Adad I / Ishme-Dagan I vs. Hammurabi The synchronization of Hammurabi and the ruling family of Shamshi-Adad I’s kingdom can be proven by the correspondence between them, including the letters of Yasmah-Addu, the ruler of Mari and younger son of Shamshi-Adad I, to Hammurabi as well as an official named Hulalum in Babylon1 and those of Ishme-Dagan I to Hammurabi.2 Landsberger proposed that Shamshi-Adad I might still have been alive during the first ten years of Hammurabi’s reign and that the first year of Ishme- Dagan I would have been the 11th year of Hammurabi’s reign.3 However, it was also suggested that Shamshi-Adad I would have died in the 12th / 13th4 or 17th / 18th5 year of Hammurabi’s reign and Ishme-Dagan I in the 28th or 31st year.6 If so, the reign length of Ishme-Dagan I recorded in the AKL might be unreliable and he would have ruled as the successor of Shamshi-Adad I only for about 11 years.7 1 van Koppen, MARI 8 (1997), 418–421; Durand, DÉPM, No. 916. 2 Charpin, ARM 26/2 (1988), No. 384. 3 Landsberger, JCS 8/1 (1954), 39, n. 44. 4 Whiting, OBOSA 6, 210, n. 205. 5 Veenhof, AP, 35; van de Mieroop, KHB, 9; Eder, AoF 31 (2004), 213; Gasche et al., MHEM 4, 52; Gasche et al., Akkadica 108 (1998), 1–2; Charpin and Durand, MARI 4 (1985), 293–343. -

Counting Days in Ancient Babylon: Eclipses, Omens, and Calendrics During the Old Babylonian Period (1750-1600 Bce)

COUNTING DAYS IN ANCIENT BABYLON: ECLIPSES, OMENS, AND CALENDRICS DURING THE OLD BABYLONIAN PERIOD (1750-1600 BCE) by Steven Jedael A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies Charlotte 2016 Approved by: Dr. John C. Reeves Dr. Steven Falconer Dr. Dennis Ogburn ii Copyright ©2016 Steven Jedael ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT STEVEN JEDAEL. Counting days in ancient Babylon: eclipses, omens, and calendrics during the Old Babylonian period (1750-1600 bce). (Under the direction of DR. JOHN C. REEVES) Prior to the sixth century BCE, each lunar month of the Babylonian calendar is believed to have been determined solely by direct observation of the new moon with the insertion of intercalary months arbitrarily dictated by the king and his advisors. However, lunar eclipse omens within the divination texts of the Enūma Anu Enlil, some which date to the second half of the Old Babylonian period (ca. 1750-1600 BCE), clearly indicate a pattern of lunar eclipses occurring on days 14, 15, 16, 20, and 21 of the lunar month—a pattern suggesting an early schematic structure. In this study, I argue that observed period relations between lunar phases, equinoxes, and solstices as well as the invention of the water clock enabled the Babylonians to become aware of the 8-year lunisolar cycle (known as the octaeteris in ancient Greece) and develop calendars with standardized month-lengths and fixed rules of intercalation during the second millennium BCE. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES vi LIST OF FIGURES vii LIST OFABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS viii LIST OF STANDARD MESOPOTAMIAN MONTHS (SUMERIAN x LOGOGRAPHIC SPELLINGS) CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. -

The Life and Times of Isaiah for Commercial Purposes Or to Attain Personal Gain Or Advantage

©2020 Mike Whyte - this document may be used freely for personal study, preaching, and teaching. No part of it may be used under any circumstances The Life and Times of Isaiah for commercial purposes or to attain personal gain or advantage. Assyrian Kings: Ashur-dan III Ashur-nirari V Shalmaneser V Esarhaddon (771-754) (753-746) Tiglath-pileser III (745-727) (726-722) Sargon II (721-705) Sennacherib (704-681) (680-669) Babylonian Kings: Pulu (Pul, Tiglath-pileser III) Merodach-baladin Belibni Ashur-nadin-shumi (699-694) Nergel-ushezib Mushezib-marduk Nabonassar (747-734) (728-727) (721-710, again 703) (702-700) son of Sennacherib (693) (692-689) Egyptian Kings: Dynasty 22, 23, & 24 many concurrent Pharaohs - before 716 Dynasty 25 (Nubian): Piankhi (747-716) Shabaqo (716-702) Shabitqo (702-690) Tirhakah (690-664) North Israelite Kings: Zechariah (752) Menahem Pekahiah Pekah Hoshea Jeroboam II (781-753) Shallum (752) (752-741) (741-739) (739-731) (731-724) South Israelite Kings: Jotham (739-730) Ahaz (730-715) Hezekiah (715-686) Manasseh (686-643) (co-regent with (co-regent with (co-regent with Ahaz (co-regent with Uzziah (767-739) Uzziah from 750) Jotham from 735) from 728) Hezekiah from 697) 714 - alliance led by 701 - 2Kg18:13-16, Is36:1 first invasion of 688 - 2Kg18:17-36, Assyria weak until 732 - 2Kg15:29 Tiglath-pileser 725 - 2K17:3-6 Hoshea Ashdod, including Sennacherib: Egyptian army comes to support 19:1-35//Is36:2-22, 681 - Tiglath-pileser destroys Damascus, reduces withholds tribute; seeks Egypt weak until Piankhi Edom, Moab, -

A Spatial Analysis of the Akītu Festival in Babylon After 626 BCE

Balancing Power and Space: a Spatial Analysis of the Akītu Festival in Babylon after 626 BCE Andrew Alberto Nicolas Deloucas Student Number: 1573241 June 30, 2016 Research Master’s Thesis for Classical and First Reader: Caroline Waerzeggers Ancient Civilizations (Assyriology) Second Reader: J.G. Dercksen Universiteit Leiden Table of Contents Chapter I: Balancing Power and Space 1. Introduction…..…………………………………………………...……………….... 1 2. Past and Recent Scholarship……………………………………….……................... 2 3. Goals of this Study……….…………………………………………………………. 5 4. Methodology……………………….……………………………………………..... 6 5. Theory…………...……………………………………………………………….…. 7 Chapter II: The Neo-Babylonian Period 1. Chronicles………………………………………………………………………….. 13 2. Royal Inscriptions………………………………………………………………….. 21 3. Analysis……………..……………………………………………………………... 27 Chapter III: The Persian Period 1. The Cyrus Cylinder and Verse Account.…………...….…………………………... 32 2. ABC 1A-1C…...…………………………………………………………………… 37 3. Xerxes and Onward. ………………….………………….…………………..……. 38 4. Analysis……………………………………………………………………………. 40 Chapter IV: The Hellenistic Period 1. Cultic Texts..………………………………..……………………………………… 42 2. Chronicles………………………………………………………………………….. 56 3. Analysis…………………………………………...……………………………….. 60 Chapter V: Conclusions 1. Synthesis of Material……….……...………………………………………………. 64 2. Conclusions……..………………………….........…………………………………. 71 3. Abbreviations and.Bibliography …..……….........………………………………… 75 Andrew Deloucas 1. Introduction a. Babylon Babylon as it appeared throughout history seems to be a city -

Xerxes and Babylonia

ORIENTALIA LOVANIENSIA ANALECTA Xerxes and Babylonia The Cuneiform Evidence edited by CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS and MAARJA SEIRE PEETERS XERXES AND BABYLONIA: THE CUNEIFORM EVIDENCE ORIENTALIA LOVANIENSIA ANALECTA ————— 277 ————— XERXES AND BABYLONIA The Cuneiform Evidence edited by CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS and MAARJA SEIRE PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – BRISTOL, CT 2018 A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. © 2018, Peeters Publishers, Bondgenotenlaan 153, B-3000 Leuven/Louvain (Belgium) This is an open access version of the publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial reproduction and distribution of the work, in any medium, provided the original work is not altered or transformed in any way, and that the work is properly cited. ISBN 978-90-429-3670-6 eISBN 978-90-429-3809-7 D/2018/0602/119 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS . VII CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS Introduction: Debating Xerxes’ Rule in Babylonia . 1 REINHARD PIRNGRUBER Towards a Framework for Interpreting Social and Economic Change in Babylonia During the Long 6th Century BCE . 19 MAŁGORZATA SANDOWICZ Before Xerxes: The Role of the Governor of Babylonia in the Administration of Justice Under the First Achaemenids . 35 MICHAEL JURSA Xerxes: The Case of Sippar and the Ebabbar Temple . 63 KARLHEINZ KESSLER Uruk: The Fate of the Eanna Archive, the Gimil-Nanāya B Archive, and Their Archaeological Evidence . 73 CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS The Network of Resistance: Archives and Political Action in Baby- lonia Before 484 BCE . 89 MATHIEU OSSENDRIJVER Babylonian Scholarship and the Calendar During the Reign of Xerxes .