Postcolonial Literatures on Genocide and Capital Shashi Thandra Wayne State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statelessness and Citizenship in the East African Community

Statelessness and Citizenship in the East African Community A Study by Bronwen Manby for UNHCR September 2018 Commissioned by UNHCR Regional Service Centre, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] STATELESSNESS AND CITIZENSHIP IN THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY 2 September 2018 STATELESSNESS AND CITIZENSHIP IN THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... i List of Boxes ................................................................................................................................ i Methodology and acknowledgements ...................................................................................... ii A note on terminology: “nationality”, “citizenship” and “stateless person” ........................... iii Acronyms .................................................................................................................................. iv Key findings and recommendations ....................................................................... 1 1. Summary ........................................................................................................... 3 Overview of the report .............................................................................................................. 4 Key recommendations .............................................................................................................. 5 Steps already taken .................................................................................................................. -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Inequality of Child Mortality Among Ethnic Groups in Sub-Saharan Africa M

Special Theme ±Inequalities in Health Inequality of child mortality among ethnic groups in sub-Saharan Africa M. Brockerhoff1 & P. Hewett2 Accounts by journalists of wars in several countries of sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s have raised concern that ethnic cleavages and overlapping religious and racial affiliations may widen the inequalities in health and survival among ethnic groups throughout the region, particularly among children. Paradoxically, there has been no systematic examination of ethnic inequality in child survival chances across countries in the region. This paper uses survey data collected in the 1990s in 11 countries (Central African Republic, Coà te d'Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda, and Zambia) to examine whether ethnic inequality in child mortality has been present and spreading in sub-Saharan Africa since the 1980s. The focus was on one or two groups in each country which may have experienced distinct child health and survival chances, compared to the rest of the national population, as a result of their geographical location. The factors examined to explain potential child survival inequalities among ethnic groups included residence in the largest city, household economic conditions, educational attainment and nutritional status of the mothers, use of modern maternal and child health services including immunization, and patterns of fertility and migration. The results show remarkable consistency. In all 11 countries there were significant differentials between ethnic groups in the odds of dying during infancy or before the age of 5 years. Multivariate analysis shows that ethnic child mortality differences are closely linked with economic inequality in many countries, and perhaps with differential use of child health services in countries of the Sahel region. -

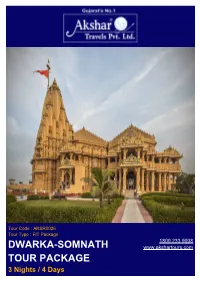

Dwarka-Somnath Tour Package

Tour Code : AKSR0026 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 DWARKA-SOMNATH www.akshartours.com TOUR PACKAGE 3 Nights / 4 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 4Cities 4Days 1Activities Accomodation Meal 02 NIGHTS ACCOMODATION IN DWARKA 03 BREAKFAST 03 DINNER 01 NIGHT ACCOMODATION IN SOMNATH Visa & Taxes Highlights Accommodation on double sharing 5% Gst Extra Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Jamnagar : Lakhota lake , Lakhota museum and Bala hanuman temple. - Dwarka : Bet Dwarka , Nageshwar Jyotirlinga , Rukmani Temple. - Porbandar : Kirti mandir (Gandhiji birth place), Sudama Temple. - Somnath : Somnath jyotirlinga, Triveni sangam, Bhalka tirth. SIGHTSEEINGS JAMNAGAR On an island in the center of the lake stands the circular Lakhota tower, built for drought relief on orders from Jam Ranmalji after the failed monsoons in 1834, 1839 and 1846 made it difficult for the people of the city to find food and resources. Originally designed as a fort such that soldiers posted around it could fend off an invading enemy army with the lake acting as a moat, the tower known as Lakhota Palace now houses the Lakhota Museum. The collection includes artifacts spanning from 9th to 18th century, pottery from medieval villages nearby and the skeleton of a whale. The very first thing you see on entry, however, before the historical and archaeological information, is the guardroom with muskets, swords and powder flasks, reminding you of the structure’s original purpose and proving the martial readiness of the state at the time. The walls of the museum are also covered in frescoes depicting various battles fought by the Jadeja Rajputs. -

Burundian Refugees in Western Tanzania, It Can Be Expected That Such Activities Would Take Place

BURUNDIAN REFUGEES IN TANZANIA: The Key Factor to the Burundi Peace Process ICG Central Africa Report N° 12 30 November 1999 PROLOGUE The following report was originally issued by the International Crisis Group (ICG) as an internal paper and distributed on a restricted basis in February 1999. It incorporates the results of field research conducted by an ICG analyst in and around the refugee camps of western Tanzania during the last three months of 1998. While the situation in Central Africa has evolved since the report was first issued, we believe that the main thrust of the analysis presented remains as valid today as ever. Indeed, recent events, including the killing of UN workers in Burundi and the deteriorating security situation there, only underscore the need for greater attention to be devoted to addressing the region’s unsolved refugee problem. With this in mind, we have decided to reissue the report and give it a wider circulation, in the hope that the information and arguments that follow will help raise awareness of this important problem and stimulate debate on the best way forward. International Crisis Group Nairobi 30 November 1999 Table of Contents PROLOGUE .......................................................................................................................................... I I. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 II. REFUGEE FLOWS INTO TANZANIA....................................................................................... -

Congolese Refugees

Congolese refugees A protracted situation Situation overview As of 1 January 2014,1 almost half a million refugees Due to the size and the protracted nature of the had fled the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Congolese refugee situation and the on-going violence in making the DRC refugee population the sixth largest in eastern DRC, a common sub-regional approach to the world. Various conflicts since the 1960s have created enhance durable solutions for Congolese refugees within Congolese refugees, and refugees from the DRC now a comprehensive solutions strategy was introduced in represent 18 per cent of the total refugee population in early 2012. This strategy includes significantly increased Africa. resettlement of Congolese refugees who are living in a protracted situation in the Great Lakes and Southern Among the 455,522 Congolese refugees registered in Africa region. In order to implement the resettlement Africa as of 1 January 2014, some 50 per cent (225,609 strategy in a regionally harmonized manner and taking persons) are in the Great Lakes Region, into account reservations towards resettlement, such as approximately 39 per cent (177,751 persons) are in the pull factors and processing capacity, refugees East and Horn of Africa, and 11 per cent (52,162) are in considered for resettlement are being profiled according the Southern Africa region. to two main criteria: In Burundi and Rwanda, Congolese refugees represent over 99 per cent of the total registered refugee Arrival in country of asylum from 1 January 1994 to population. In Tanzania and Uganda, Congolese 31 December 2005; refugees represent approximately 65 per cent of the total registered refugee population. -

Stereotypes As Sources of Conflict in Uganda

Stereotypes as Sources of Conflict in Uganda Justus NIL, gaju Editorial Consultant/BMG Wordsmith, Kampala Email: ibmugâ;u ;a yahoo.co.uk In order- to govern, colonial authorities had frequently found it expedient to divide in order to rule. An example of such a situation was, for instance, the dividing up of Uganda into a society of contradictory and mutually suspicious interests. They made, for instance, the central area of the country, and to some extent, areas in the east, produce cash crops for export. In so doing they made one part of Uganda produce cash crops and another reservoir of cheap labour and of recruitment into the colonial army. This had the inevitability of producing inequalities, which in turn generated intense and disruptive conflicts between the different ethnic groups involved. The rivalry over access to opportunities gave rise to the formation of attitudes of superiority and inferiority complexes. President Yoweri Museveni (MISR, 1987:20) The history of modern Uganda is a long story of stereotyping. From the beginning of colonial rule to the present, the history of Uganda has been reconstructed in neat- looking but deceptive stereotypes. These stereotypes can be summed up as follows: aliens and natives, centralised/developed/sophisticated states versus primitive stateless societies, the oppressor and the oppressed, the developed north and the backward north, the rulers and subjects, and the monarchists/traditionalists and the republicans. Uganda's history has also been reconstructed in terms of the "modermsers" versus the "Luddites", patriots against quislings, heroes/martyrs and villains, the self-serving elite and the long-suffering oppressed/exploited masses, the "swine" versus the visionary leaders, the spineless politicians and the blue-eyed revolutionaries, etc. -

Download This PDF File

The International Journal Of Humanities & Social Studies (ISSN 2321 - 9203) www.theijhss.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES Hutu-Tutsi Conflict in Burundi: A Critical Exploration of Factors Dr. Mpawenimana Abdallah Saidi Vice Principal, Baseerah International School, Shah Alam, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Oladimeji Talibu Ph.D. Candidate, School of International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia Abstract: The scenario of genocidal war that broke out in 1994 in Burundi and Rwanda is the worst of its kind that ever happened on the African continent. The war broke out between the two major ethnic groups, Hutu and Tutsi, in Rwanda and Burundi which led to the death of over 800,000 people in both countries. The failure of the international community, the regional body and the East African Community, to instantaneously intervene to prevent the genocide war has been given scholarly attention by scholars whereas the main factors behind the outbreak of the war have not been properly delved into. Given the currency of the issue in the East African region, the article examines those factors that have given rise to the Hutu-Tutsi conflict in Burundi. It seeks to provide an analytical framework upon which the conflict can be understood. In this way, the article presents Burundi as a case study. It is believed that understanding Burundi scenario can shed light on those factors that led to the war in both Burundi and Rwanda. In doing this, we rely on existing works and documents of which we employed content analysis to critically interpret. Keywords: Burundi, Hutu, Tutsi, geography, economics, politics 1. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Alagwa in Tanzania Arab in Tanzania Population: 58,000 Population: 270,000 World Popl: 58,000 World Popl: 703,600 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 31 People Cluster: Sub-Saharan African, other People Cluster: Arab, Arabian Main Language: Alagwa Main Language: Swahili Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.02% Evangelicals: 0.60% Chr Adherents: 0.02% Chr Adherents: 5.00% Scripture: Portions Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Erik Laursen, New Covenant Missi Source: Pat Brasil "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Assa in Tanzania Baganda in Tanzania Population: 700 Population: 60,000 World Popl: 700 World Popl: 8,800,200 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 6 People Cluster: Khoisan People Cluster: Bantu, Makua-Yao Main Language: Maasai Main Language: Ganda Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Christianity Status: Unreached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 0.30% Evangelicals: 13.0% Chr Adherents: 5.00% Chr Adherents: 80.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Masters View / Howard Erickson "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Bajuni in Tanzania Bemba in Tanzania Population: 24,000 Population: 5,500 World -

Inter-Ethnic Marriages, the Survival of Women, and the Logics of Genocide in Rwanda

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 4 November 2007 Inter-ethnic Marriages, the Survival of Women, and the Logics of Genocide in Rwanda Anuradha Chakravarty Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Chakravarty, Anuradha (2007) "Inter-ethnic Marriages, the Survival of Women, and the Logics of Genocide in Rwanda," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 2: Iss. 3: Article 4. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol2/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interethnic Marriages, the Survival of Women, and the Logics of Genocide in Rwanda Anuradha Chakravarty Department of Government, Cornell University This article focuses on the gendered dimensions of the genocide in Rwanda. It seeks to explain why Tutsi women married to Hutu men appeared to have better chances of survival than Tutsi women married to Tutsi men or even Hutu women married to Tutsi men. Based on data from a field site in southwest Rwanda, the findings and insights offered here draw on the gendered, racial, and operational dynamics of the genocide as it unfolded between April and July 1994. Introduction In September 1992, a military commission report in Rwanda officially defined the ‘‘main enemy’’ as ‘‘Tutsis from inside or outside the country’’ and the ‘‘secondary enemy’’ as ‘‘anyone providing any kind of assistance to the main enemy.’’1 Since the invasion of Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels in 1990, extremist propaganda had focused on the immutable racial distinction between Hutu and Tutsi. -

Rwanda's Hutu Extremist Insurgency: an Eyewitness Perspective

Rwanda’s Hutu Extremist Insurgency: An Eyewitness Perspective Richard Orth1 Former US Defense Attaché in Kigali Prior to the signing of the Arusha Accords in August 1993, which ended Rwanda’s three year civil war, Rwandan Hutu extremists had already begun preparations for a genocidal insurgency against the soon-to-be implemented, broad-based transitional government.2 They intended to eliminate all Tutsis and Hutu political moderates, thus ensuring the political control and dominance of Rwanda by the Hutu extremists. In April 1994, civil war reignited in Rwanda and genocide soon followed with the slaughter of 800,000 to 1 million people, primarily Tutsis, but including Hutu political moderates.3 In July 1994 the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) defeated the rump government,4 forcing the flight of approximately 40,000 Forces Armees Rwandaises (FAR) and INTERAHAMWE militia into neighboring Zaire and Tanzania. The majority of Hutu soldiers and militia fled to Zaire. In August 1994, the EX- FAR/INTERAHAMWE began an insurgency from refugee camps in eastern Zaire against the newly established, RPF-dominated, broad-based government. The new government desired to foster national unity. This action signified a juxtaposition of roles: the counterinsurgent Hutu-dominated government and its military, the FAR, becoming insurgents; and the guerrilla RPF leading a broad-based government of national unity and its military, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), becoming the counterinsurgents. The current war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DROC), called by some notable diplomats “Africa’s First World War,” involving the armies of seven countries as well as at least three different Central African insurgent groups, can trace its root cause to the 1994 Rwanda genocide. -

Gendered War and Rumors of Saddam Hussein in Uganda

Gendered War and Rumors of Saddam Hussein in Uganda SVERKER FINNSTRÖM Department of Social Anthropology Stockholm University SE 10691 Stockholm, Sweden SUMMARY This article discusses the role of rumors in everyday Acholi life in war-torn northern Uganda. These rumors concern various health threats such as HIV and Ebola. The rumors are closely associated with the forces of domination that are alleged to destroy female sexuality and women’s reproductive health and, by extension, Acholi humanity. Moreover, the rumors are stories that say something profound about lived entrapments and political asymmetries in Uganda and beyond. [Keywords: rumors, war, gender, health, Uganda] In this article, I explore rumors as interpretive and indeed very real commen- taries on wartime violence, gender hierarchies, and various health threats such as HIV and Ebola. My focus is on the Acholi in northern Uganda who struggle to find directionality in the shadows of a bitter civil war, and how they expe- rience war and construct meaning as they live in intersection with the wider world. Rumors are central to propaganda machineries in all war settings, I argue. They are stories that link the personal with the political and the local with the national and even the global. Rumors figure strongly in the social memory of war-torn Acholiland, deepening the idea that the Acholi are being subjected to a slow genocide, which is staged by the central government and other outside powers, including the international community. Sometimes my Acholi friends suggested that the hidden agenda was to have the war continue by every means, a war that for so many years has been good business for rebels, high-ranking army officers, and humanitarian aid workers, but ultimately was believed to be the end of the Acholi people.