The * Droppers' of Tulipa and Erythronium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liliaceae S.L. (Lily Family)

Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) Photo: Ben Legler Photo: Hannah Marx Photo: Hannah Marx Lilium columbianum Xerophyllum tenax Trillium ovatum Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) Photo: Yaowu Yuan Fritillaria lanceolata Ref.1 Textbook DVD KRR&DLN Erythronium americanum Allium vineale Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) Herbs; Ref.2 Stems often modified as underground rhizomes, corms, or bulbs; Flowers actinomorphic; 3 sepals and 3 petals or 6 tepals, 6 stamens, 3 carpels, ovary superior (or inferior). Tulipa gesneriana Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) “Liliaceae” s.l. (sensu lato: “in the broad sense”) - Lily family; 288 genera/4950 species, including Lilium, Allium, Trillium, Tulipa; This family is treated in a very broad sense in this class, as in the Flora of the Pacific Northwest. The “Liliaceae” s.l. taught in this class is not monophyletic. It is apparent now that the family should be treated in a narrower sense and some of the members should form their own families. Judd et al. recognize 15+ families: Agavaceae, Alliaceae, Amarylidaceae, Asparagaceae, Asphodelaceae, Colchicaceae, Dracaenaceae (Nolinaceae), Hyacinthaceae, Liliaceae, Melanthiaceae, Ruscaceae, Smilacaceae, Themidaceae, Trilliaceae, Uvulariaceae and more!!! (see web reading “Consider the Lilies”) Iridaceae (Iris family) Photo: Hannah Marx Photo: Hannah Marx Iris pseudacorus Iridaceae (Iris family) Photo: Yaowu Yuan Photo: Yaowu Yuan Sisyrinchium douglasii Sisyrinchium sp. Iridaceae (Iris family) Iridaceae - 78 genera/1750 species, Including Iris, Gladiolus, Sisyrinchium. Herbs, aquatic or terrestrial; Underground stems as rhizomes, bulbs, or corms; Leaves alternate, 2-ranked and equitant Ref.3 (oriented edgewise to the stem; Gladiolus italicus Flowers actinomorphic or zygomorphic; 3 sepals and 3 petals or 6 tepals; Stamens 3; Ovary of 3 fused carpels, inferior. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

Embryological and Cytological Features of Gagea Bohemica (Liliaceae)

Turk J Bot 36 (2012) 462-472 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1107-11 Embryological and cytological features of Gagea bohemica (Liliaceae) Filiz VARDAR*, Işıl İSMAİLOĞLU, Meral ÜNAL Department of Biology, Science and Arts Faculty, Marmara University, 34722 Göztepe, İstanbul - TURKEY Received: 19.07.2011 ● Accepted: 29.02.2012 Abstract: Th e present study describes the developmental features of the embryo sac and ovular structures, particularly the obturator, during development in Gagea bohemica (Zauschn.) Schult. & Schult. f. Th e nucellar epidermis is poorly developed and composed of 1-2 layers of cuboidal cells. Th e tissue at the chalazal end of the nucellus diff erentiates into a hypostase. Th e micropyle is formed by the inner integument and composed of 4-5 cell layers that include starch grains. Th e functional megaspore results in an 8-nucleated embryo sac and conforms to a tetrasporic, Fritillaria L. type. Cytoplasmic nucleoloids consisting of protein and RNA are obvious during megasporogenesis. Th e obturator attracts attention during embryo sac development. Cytochemical tests indicated that the cells of the obturator present a strong reaction in terms of insoluble polysaccharide, lipid, and protein. Obturator cells are coated by a smooth and thick surface layer that starts to accumulate partially and then merges. Ultrastructural studies reveal that obturator cells are rich in rough endoplasmic reticulum, polysomes, plastids with osmiophilic inclusions, dictyosomes with large vesicles, mitochondria, and osmiophilic secretory granules. Aft er fertilisation, the vacuolisation in obturator cells increases by fusing small vacuoles to form larger ones. Some of the small vacuoles contain electron dense deposits. -

The Alien Vascular Flora of Tuscany (Italy)

Quad. Mus. St. Nat. Livorno, 26: 43-78 (2015-2016) 43 The alien vascular fora of Tuscany (Italy): update and analysis VaLerio LaZZeri1 SUMMARY. Here it is provided the updated checklist of the alien vascular fora of Tuscany. Together with those taxa that are considered alien to the Tuscan vascular fora amounting to 510 units, also locally alien taxa and doubtfully aliens are reported in three additional checklists. The analysis of invasiveness shows that 241 taxa are casual, 219 naturalized and 50 invasive. Moreover, 13 taxa are new for the vascular fora of Tuscany, of which one is also new for the Euromediterranean area and two are new for the Mediterranean basin. Keywords: Vascular plants, Xenophytes, New records, Invasive species, Mediterranean. RIASSUNTO. Si fornisce la checklist aggiornata della fora vascolare aliena della regione Toscana. Insieme alla lista dei taxa che si considerano alieni per la Toscana che ammontano a 510 unità, si segnalano in tre ulteriori liste anche i taxa che si ritengono essere presenti nell’area di studio anche con popolazioni non autoctone o per i quali sussistono dubbi sull’effettiva autoctonicità. L’analisi dello status di invasività mostra che 241 taxa sono casuali, 219 naturalizzati e 50 invasivi. Inoltre, 13 taxa rappresentano una novità per la fora vascolare di Toscana, dei quali uno è nuovo anche per l’area Euromediterranea e altri due sono nuovi per il bacino del Mediterraneo. Parole chiave: Piante vascolari, Xenofte, Nuovi ritrovamenti, Specie invasive, Mediterraneo. Introduction establishment of long-lasting economic exchan- ges between close or distant countries. As a result The Mediterranean basin is considered as one of this context, non-native plant species have of the world most biodiverse areas, especially become an important component of the various as far as its vascular fora is concerned. -

Checklist of the Vascular Alien Flora of Catalonia (Northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3

BOTANICAL CHECKLISTS Mediterranean Botany ISSNe 2603-9109 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/mbot.63608 Checklist of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3 Received: 7 March 2019 / Accepted: 28 June 2019 / Published online: 7 November 2019 Abstract. This is an inventory of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) updated to 2018, representing 1068 alien taxa in total. 554 (52.0%) out of them are casual and 514 (48.0%) are established. 87 taxa (8.1% of the total number and 16.8 % of those established) show an invasive behaviour. The geographic zone with more alien plants is the most anthropogenic maritime area. However, the differences among regions decrease when the degree of naturalization of taxa increases and the number of invaders is very similar in all sectors. Only 26.2% of the taxa are more or less abundant, while the rest are rare or they have vanished. The alien flora is represented by 115 families, 87 out of them include naturalised species. The most diverse genera are Opuntia (20 taxa), Amaranthus (18 taxa) and Solanum (15 taxa). Most of the alien plants have been introduced since the beginning of the twentieth century (70.7%), with a strong increase since 1970 (50.3% of the total number). Almost two thirds of alien taxa have their origin in Euro-Mediterranean area and America, while 24.6% come from other geographical areas. The taxa originated in cultivation represent 9.5%, whereas spontaneous hybrids only 1.2%. From the temporal point of view, the rate of Euro-Mediterranean taxa shows a progressive reduction parallel to an increase of those of other origins, which have reached 73.2% of introductions during the last 50 years. -

Winter 2004.Pmd

The Lady-Slipper, 19:4 / Winter 2004 1 The Lady-Slipper Kentucky Native Plant Society Number 19:4 Winter 2004 A Message from the President: It’s Membership Winter is upon us. I hope everyone had some opportunity to experience the colors of Fall and now some of us will turn our attention to winter botany. While I was unable to Renewal Time! attend, I understand that our Fall meeting at Shakertown Kentucky Native Plant Society with Dr. Bill Bryant from Thomas More College as the guest EMBERSHIP ORM speaker was a great success. M F Our Native Plant Certification program was relatively successful this Fall. Plant taxonomy failed to meet Name(s) ____________________________________ because the NKU’s Community Education Bulletin was Address ____________________________________ mailed too late for anyone to sign up for the course. The woody plants course did, however, have a successful run. City, State, Zip ______________________________ This coming Spring, we will be offering Basic Plant Taxonomy, Plant Communities and Spring Wildflowers of KY County __________________________________ Central Kentucky. Tel.: (home) ______________________________ You will see in this issue that we are promoting “Chinquapin” the newsletter of the Southern Appalachian (work) ______________________________ Botanical Society (SABS). SABS is an organization E-mail _______________________________ largely made up of professional botanists and produces a quarterly scholarly journal. The newsletter “Chinquapin” o Add me to the e-mail list for time-critical native plant news has more of a general interest approach much like our o Include my contact info in any future KNPS Member Directory newsletter but on a regional scale. In this issue we have Membership Categories: provided subscription information on page 7. -

Lily (Erythronium Albidium) in Cameron Park of the Trout Lily in Cameron Park

Impact of Ligustrum lucidum on White Trout Lily 2 towards the production of fl owering ramets involved in producing new Impact of Ligustrum lucidum on Leaf Morphology, plants. Thus, the average increase in petiole and leaf lengths in these single-year data indicate the privet is suppressing populations of native Chlorophyll, and Flower Morphology of White Trout spring ephemerals, such as white trout lily, and altering the morphology Lily (Erythronium albidium) in Cameron Park of the trout lily in Cameron Park. Sarah J. Garza and Dr. Susan Bratton Introduction Abstract From water hyacinth crowding out native lake plants to zebra mussels competing with native clams, exotic species invasion threatens the Invasion of non native species is reducing biodiversity worldwide. biodiversity of many different ecosystems worldwide. This well-studied Shining privet (Ligustrum lucidum W.T. Aiton), a sub-canopy tree native phenomenon is the most serious threat to the long-term preservation to Asia, is diminishing native understory fl ora in Cameron Park in of native forest in William B. Cameron Park, located in Waco, Texas. Waco, Texas. Previous data from Cameron Park indicates that privet is Cameron Park incorporates relic forest vernal herb communities, which suppressing the vernal ephemeral, white trout lily (Erythronium albidium are prone to species loss from disturbance. Cameron Park also provides Nutt), in ravines above the Brazos River. a contiguous block of habitat for forest birds otherwise excluded from In February 2008, a research team from Baylor University’s fragmented urban habitats. Seeds of ornamental trees and shrubs, Environmental Studies Department sampled trout lily populations to some originating from lawns in or near the park and some traveling test the hypothesis that greater privet cover increases leaf and petiole longer distances via birds or other dispersal mechanisms, have produced (stem) length of the ramets (individual plants) while it decreases the scattered populations of exotic plants throughout the park. -

Tulip, Saxatilis Spring-Flowering Bulb

Tulip, Saxatilis Spring-Flowering Bulb Tulipa saxatilis Liliaceae Family These compact 8- to 10-inch-tall tulips bear delicate but showy sweet- scented, pale pink or purple blooms with yellow centers. It is well-suited to rock garden use. Site Characteristics Plant Traits Special Considerations Sunlight: Lifecycle: perennial Special characteristics: . full sun Ease-of-c a r e : easy . non-aggressive - Spreads by runners. Soil conditions: Height: 0.75 to 1 feet . non-invasive . not native to North America - . tolerates droughty soil Spread: 0.25 to 0.5 feet Native to Crete and Turkey . requires well-drained soil . fragrant - Blooms are sweetly Bloom time: scented. Prefers fertile, well drained soil. mid-spring Special uses: Hardiness zones: . late spring . 5 to 9 Flower color: Special locations: . yellow . violet . outdoor containers . white . rock gardens . pink . xeriscapes Blooms are pale pink or violet with yellow markings edged in white. Foliage color: medium green Foliage texture: me di u m Shape: upright Shape in flower: flower stalks with flowers as cups Blooms borne in groups of up to 4 per plant. Growing Information How to plant: Propagate by division or separation - Divide the bulbs in the fall, when clumps have become overcrowded. Plant the bulbs 5" beneath the soil surface. Maintenance and care: Remove faded flowers after blooming. After spring blooming, allow the foliage to die back (about 6 weeks) before cutting back. Do not cut back unfaded foliage. More growing information: How to Grow Bulbs Pests: Slugs and snails Aphids Diseases: Bulb rot Root rot Gray mold Nematodes ©2006 Cornell U n i v e r s i t y . -

Tulip Meadows of Kazakhstan & the Tien Shan Mountains

Tulip Meadows of Kazakhstan & the Tien Shan Mountains Naturetrek Tour Report 12 - 27 April 2008 Tulipa ostrowskiana Tulipa buhsiana Tulipa kauffmanaina Tulipa gregeii Report & images compiled by John Shipton Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Tulip Meadows of Kazakhstan & the Tien Shan Mountains Tour Leaders: Anna Ivanshenko (Local Guide) John Shipton (Naturetrek Leader) Translator Yerken Kartanbeyovich Participants: Diane Fuell Andrew Radgick Jennifer Tubbs Christina Hart-Davies Day 1 Saturday 12th April Travelling from the UK Day 2 Sunday 13th April LAKE KAPCHAGAI We arrived at Almaty at dawn. I had to negotiate with the rapacious taxi drivers to take us to the Otrar hotel was booked ready for us, and Julia from the local agents office, phoned soon after to let us know the day’s plan. This allowed us two hours rest before breakfast. At 10am Julia introduced us to Anna and Yerken and we drove with driver Yerlan two hours (80km) north out of town to Lake Kapchagai by the dam on the Ili River. Starting from the rather dilapidated industrial scene and negotiating a crossing of the main road with two imposing policeman we started on the west side of the road. Almost immediately we saw Tulipa kolpakowskiana in flower and our first Ixiolirion tartaricum. Further up the bank we found wonderful specimens of Tulipa albertii, although many flowers had already gone over as spring apparently was unusually advanced. Our tally of Tulips was increased by Tulipa buhsiana but not in flower. -

Tulips of the Tien Shan Kazakhstan Greentours Itinerary Wildlife

Tulips of the Tien Shan A Greentours Itinerary Days 1 & 2 Kapchagai After our overnight flight from the UK one can relax in the hotel or start in the sands of the Kapchagai where we’ll have our first meeting with the wonderful bulbous flora of the Central Asian steppes. Tulips soon start appearing, here are four species, and all must be seen today as they do not occur in the other parts of Kazakhstan we visit during the tour! These special species include a lovely yellow form of Tulipa albertii which blooms amidst a carpet of white blossomed Spiraea hypericifolia subshrubs. Elegant Eremurus crispus can be seen with sumptuous red Tulipa behmiana, often in company with pale Gagea ova, abundant Gagea minutiflora and local Gagea tenera. There are myriad flowers as the summer sun will not yet have burnt the sands dry. Low growing shrubs of Cerasus tianshanicus, their pale and deep pink blooms perfuming the air, shelter Rindera cyclodonta and Corydalis karelinii. In the open sandy areas we’ll look for Iris tenuifolia and both Tulipa talievii and the yellow-centred white stars of Tulipa buhseana. We’ll visit a canyon where we can take our picnic between patches of Tulipa lemmersii, a newly described and very beautiful tulip. First described in 2008 and named after Wim Lemmers, this extremely local endemic grows only on the west-facing rocks on the top of this canyon! Day 3 The Kordoi Pass and Merke After a night's sleep in the Hotel Almaty we will wake to find the immense snow- covered peaks of the Tien Shan rising from the edge of Almaty's skyline - a truly magnificent sight! We journey westwards and will soon be amongst the montane steppe of the Kordoi Pass where we will find one of the finest shows of spring flowers one could wish for. -

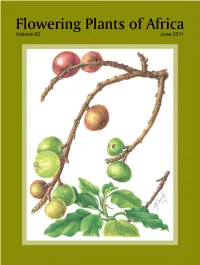

Albuca Spiralis

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J.