Volume 9, Number 1 Winter 2018 Contents ARTICLES Changing The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Thursday, March 19, 2020 * The Boston Globe Due to coronavirus outbreak, baseball’s minor leaguers are caught in a no-man’s land Alex Speier Red Sox minor leaguers worked out and played intrasquad games at the JetBlue Park complex in Fort Myers, Fla., last Friday and left the premises expecting to return for more of the same the next day. But shortly after the players scattered, the team sent out a jarring communiqué: Effective immediately, minor league camp was over. The Red Sox wanted players to collect their belongings from the park and encouraged them to head home. Upon receiving the message, outfielder Tyler Dearden, who spent last year with Single A Greenville, took to Twitter with grim humor. Sooo anybody hiring?? Sincerely, All minor league baseball players right now. “I had no idea what to expect and was kind of trying to make light of the situation,” Dearden said by phone. “But I’m pretty sure that’s a thought that ran through all minor leaguers’ heads when they found out.” Dearden’s tweet inspired dozens of comments, hundreds of retweets, and thousands of likes — many from fellow minor leaguers suddenly wondering about their employment and financial security since the COVID-19 virus led to the shutdown of minor league camps and the chaotic dispersal of players, including the roughly 180 who’d been in Red Sox minor league camp. This past offseason, Dearden lived at home in New Jersey with his parents, offered baseball lessons, and ran food deliveries for DoorDash to help him bridge from his last paycheck at the end of the minor league season to the start of spring training, while also creating a bit of extra money for the coming season. -

Charges Dismissed in SV Dorm Death Democrats Muscle

32 / 20 Happy See Business 3 Valentine’s Cloudy, snow. Day Business 4 MILC PAYMENTS >>> Declining dairy prices trigger payments to milk producers, BUSINESS 1 SATURDAY 75 CENTS February 14, 2009 MagicValley.com Charges dismissed in SV dorm death Democrats muscle dependent on the results of Prosecutors awaiting lab results, may refile toxicology and microscopic huge stimulus tissue samples taken from By Ariel Hansen tors await lab results. mates in their company dorm James’ body. The state is also Times-News writer On Monday, 20-year-old room. awaiting DNA results and Corey D. Drehmel was In a statement Friday, the analysis of blood taken from through Congress HAILEY — The suspect in a charged with involuntary Blaine County Prosecuting Drehmel, and a cause of Feb. 6 death at the Sun Valley manslaughter in the death of Attorney’s Office said that due death for James from the Ada Resort dorms has been 49-year-old Jerome James, to the circumstances and the County Coroner. Those By David Espo released, and charges against following an alleged alterca- lack of eyewitnesses, the Associated Press writer Idaho reaction him dropped, while prosecu- tion between the two room- state’s case against Drehmel is See DEATH, Main 2 WASHINGTON — In a All four members of major victory for President Idaho’s congressional del- Barack Obama, egation voted against the Democrats muscled a economic stimulus bill. huge, $787 billion stimu- Here are their reac- Kimberly S PECIAL CELEBRATION lus bill through Congress tions: late Friday night in hopes of combating the worst Rep. Walt Minnick, D economic crisis since the recall fails Great Depression. -

Out of My League

OUT OF MY LEAGUE HHayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.inddayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.indd i 111/10/111/10/11 99:20:20 AAMM HHayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.inddayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.indd iiii 111/10/111/10/11 99:20:20 AAMM OUT OF MY LEAGUE A Rookie’s Survival in the Bigs DIRK HAYHURST CITADEL PRESS Kensington Publishing Corp. www.kensingtonbooks.com HHayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.inddayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.indd iiiiii 111/10/111/10/11 99:20:20 AAMM CITADEL PRESS BOOKS are published by Kensington Publishing Corp. 119 West 40th Street New York, NY 10018 Copyright © 2012 Dirk Hayhurst All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews. All Kensington titles, imprints, and distributed lines are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, educational, or institutional use. Special book excerpts or customized printings can also be created to fi t specifi c needs. For details, write or phone the offi ce of the Kensington special sales manager: Kensington Publishing Corp., 119 West 40th Street, New York, NY 10018, attn: Special Sales Department; phone 1-800-221-2647. CITADEL PRESS and the Citadel logo are Reg. U.S. Pat. & TM Off. First printing: March 2012 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America CIP data is available. ISBN-13: 978-0-8065-3485-5 ISBN-10: 0-8065-3485-0 HHayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.inddayh_9780806534855_2p_all_r1.indd iviv 111/10/111/10/11 99:20:20 AAMM With love, I dedicate this book to my mother and father, for showing me the right path to walk in life. -

Ohio High School Baseball Coaches Association

OHIO HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION Dear OHSBCA Member, 1/20/11 Welcome to the 2011 OHSBCA State Coaches Clinic: “America’s Game”. The Ohio High School Baseball Coaches Association has become the 2nd largest high school coaches’ association in the country. Coaches, national speakers, and vendors from all over the country feel that the Ohio High School Coaches Association Clinic is one of the best in the entire country. One of my favorite quotes comes from one of this year’s clinicians; John Cohen from Mississippi St. John speaks all over the country at not only big national conventions, but small ones too. He said, “Looking forward to seeing you at the clinic. You guys are first class and run an incredible clinic.” My hope is that you will feel the same after this weekend. I would also like to take time to welcome you to the Hyatt Regency, “Downtown Columbus”, and our home for the next few days. What an outstanding and first-class setting for one of the premiere high school coaches’ clinics. Please feel free to let any of the OHSBCA Board members or I know if we can personally help or assist you in any way this weekend while here at the clinic, or throughout the year. We, the board, wish to be the best representation of all our members’ coaches and their concerns. This weekend’s lineup consists of great speakers from all over the country. I thank each and everyone of you speakers for agreeing to come speak and promote this great game of baseball. -

Shut up and Pitch: Major League Baseball's Power Struggle with Minor League Players in Senne V

Volume 28 Issue 1 Article 2 2-3-2021 Shut Up and Pitch: Major League Baseball's Power Struggle with Minor League Players in Senne v. Kansas City Royals Baseball Corp. Bernadette Berger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Procedure Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Bernadette Berger, Shut Up and Pitch: Major League Baseball's Power Struggle with Minor League Players in Senne v. Kansas City Royals Baseball Corp., 28 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 53 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol28/iss1/2 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\28-1\VLS102.txt unknown Seq: 1 27-JAN-21 15:24 Berger: Shut Up and Pitch: Major League Baseball's Power Struggle with Mi Comments SHUT UP AND PITCH: MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL’S POWER STRUGGLE WITH MINOR LEAGUE PLAYERS IN SENNE V. KANSAS CITY ROYALS BASEBALL CORP. “After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. [A]ny system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.”1 I. -

Volume 4, Number 1 Winter 2013 Contents ARTICLES Who

\\jciprod01\productn\H\hls\4-1\toc401.txt unknown Seq: 1 21-MAY-13 11:11 Volume 4, Number 1 Winter 2013 Contents ARTICLES Who Exempted Baseball, Anyway? The Curious Development of the Antitrust Exemption That Never Was Mitchell Nathanson ................................................. 1 Touching Baseball’s Untouchables: The Effects of Collective Bargaining on Minor League Baseball Players Garrett R. Broshuis ................................................ 51 Baseball Arbitration: An ADR Success Jeff Monhait ...................................................... 105 \\jciprod01\productn\H\hls\4-1\ms401.txt unknown Seq: 2 21-MAY-13 11:11 Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law Student Journals Office, Harvard Law School 1541 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-3146; [email protected] www.harvardjsel.com U.S. ISSN 2153-1323 The Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law is published semiannually by Harvard Law School students. Submissions: The Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law welcomes articles from professors, practitioners, and students of the sports and entertainment industries, as well as other related disciplines. Submissions should not exceed 25,000 words, including footnotes. All manuscripts should be submitted in English with both text and footnotes typed and double-spaced. Footnotes must conform with The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (18th ed.), and authors should be prepared to supply any cited sources upon request. All manuscripts submitted become the property of the JSEL and will not be returned to the author. The JSEL strongly prefers electronic submissions through the ExpressO online submission system at http://www.law.bepress.com/expresso. Submis- sions may also be sent via email to [email protected] or in hard copy to the address above. -

Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter

PSA/DNA Full LOA PSA/DNA Pre-Certified Not Reviewed The Jack Smalling Collection Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter Cap Anson HOF Letter 7 Al Reach Letter Deacon White HOF Cut 8 Nicholas Young Letter 1872 Jack Remsen Letter 1874 Billy Barnie Letter Tommy Bond Cut Morgan Bulkeley HOF Cut 9 Jack Chapman Letter 1875 Fred Goldsmith Cut 1876 Foghorn Bradley Cut 1877 Jack Gleason Cut 1878 Phil Powers Letter 1879 Hick Carpenter Cut Barney Gilligan Cut Jack Glasscock Index Horace Phillips Letter 1880 Frank Bancroft Letter Ned Hanlon HOF Letter 7 Arlie Latham Index Mickey Welch HOF Index 9 Art Whitney Cut 1882 Bill Gleason Cut Jake Seymour Letter Ren Wylie Cut 1883 Cal Broughton Cut Bob Emslie Cut John Humphries Cut Joe Mulvey Letter Jim Mutrie Cut Walter Prince Cut Dupee Shaw Cut Billy Sunday Index 1884 Ed Andrews Letter Al Atkinson Index Charley Bassett Letter Frank Foreman Index Joe Gunson Cut John Kirby Letter Tom Lynch Cut Al Maul Cut Abner Powell Index Gus Schmeltz Letter Phenomenal Smith Cut Chief Zimmer Cut 1885 John Tener Cut 1886 Dan Dugdale Letter Connie Mack HOF Index Joe Murphy Cut Wilbert Robinson HOF Cut 8 Billy Shindle Cut Mike Smith Cut Farmer Vaughn Letter 1887 Jocko Fields Cut Joseph Herr Cut Jack O'Connor Cut Frank Scheibeck Cut George Tebeau Letter Gus Weyhing Cut 1888 Hugh Duffy HOF Index Frank Dwyer Cut Dummy Hoy Index Mike Kilroy Cut Phil Knell Cut Bob Leadley Letter Pete McShannic Cut Scott Stratton Letter 1889 George Bausewine Index Jack Doyle Index Jesse Duryea Cut Hank Gastright Letter -

20% Off P&P Hardcover Bestsellers and All Event Titles for Members

Sunday, November 14, 1 p.m. Sunday, November 7, 1 p.m. Tuesday, November 23, 7 p.m. 7 14Nov 10 Timothy Snyder Nov 10 Washington Writers’ Publishing House Prize Winners Alan Khazei Bloodlands 23Nov 10 Washington Writers’ Publishing House is a non-profit organization Big Citizenship (Basic Books, $29.95) that has published over 50 volumes of poetry since 1973 and (PublicAffairs, $25.95) Its title pointing to the territory between Germany and nearly a dozen volumes of fiction. The press sponsors an annual & Russia, Snyder’s study investigates the dual slaughters competition for writers living in the Washington-Baltimore area. Bill Shore perpetrated from 1929 through the end of World War P&P is proud to host a reading by the 2010 winners in poetry and fiction. The Imaginations Of Unreasonable Men II by Hitler and Stalin. Focusing on victims—Ukrainian (PublicAffairs, $25.95) peasants, Jews, Poles, and Belarusians shot during the 2010 Poetry Prize Khazei is the co-founder of City Year, an international Great Terror—rather than on politics, Snyder, a professor of history at Holly Karapetkova non-profit organization through which young people Yale, shows how the combined brutality of these two dictators resulted in Words We Might One Day Say mentor, tutor, and lead children. In his inspiring new a catastrophe of unprecedented proportions. (WWPH, $15) book he outlines the ways and means of social entrepre- Widely published in literary journals, Karapetkova’s neurship. Shore, too, has an ambitious vision for social poetry concerns themes of motherhood and myth, Sunday, November 14, 5 p.m. -

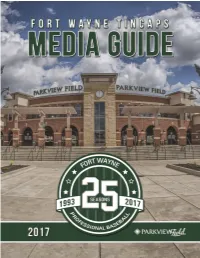

2017 Media Guide 1

2017 MEDIA GUIDE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TinCaps Club Directory ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Parkview Field/Game Day Information .................................................................................................................... 4 Fort Wayne Baseball History and Information ......................................................................................................... 5 2017 TinCaps Manager – Anthony Contreras ......................................................................................................... 7 2017 TinCaps Field Staff ......................................................................................................................................... 8 2017 Schedule…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ..... 9 A Look Back at the 2016 Season........................................................................................................................... 10 2016 Season in Review ......................................................................................................................................... 11 2016 Midwest League Final Standings .................................................................................................................. 12 2016 Midwest League Playoff Results ................................................................................................................... 12 2016 Midwest League Final Team Statistics ........................................................................................................ -

2014 Mid-American Conference Baseball Record Book

2014 Mid-American Conference Baseball Record Book WWW.MAC-SPORTS.COM 1 Mid-American Conference Baseball History Past MAC Regular Season Champions All-Time MAC Standings 1947 Ohio 1996 Kent State 1948 Ohio 1997 Ohio Year MAC Tourn. 1949 Western Michigan 1998 Ball State (West) School Entered W L T Pct. Titles Titles 1950 Western Michigan Bowling Green (East) Central Michigan 1973 590 363 1 .619 13 2 1951 Western Michigan Ball State (Overall) 1952 Western Michigan 1999 Ball State (West) Eastern Michigan 1973 614 432 2 .587 5 4 1953 Ohio Bowling Green (East) Ohio 1948 687 513 1 .572 15 1 1954 Ohio Ball State (Overall) Western Michigan 1948 676 514 2 .568 14 0 1955 Western Michigan 2000 Ball State (West) 1956 Ohio Central Michigan (West) Kent State 1952 630 519 2 .548 10 11 1957 Western Michigan Kent State (East) Miami 1948 637 584 2 .521 5 3 1958 Western Michigan Kent State (Overall) Ball State 1974 438 473 3 .481 3 1 1959 Ohio 2001 Ball State (West) Western Michigan Bowling Green (East) Bowling Green 1953 547 585 4 .483 5 2 1960 Ohio Ball State (Overall) Toledo 1952 476 676 2 .413 0 0 1961 Western Michigan 2002 Eastern Michigan (West) 1962 Western Michigan Bowling Green (East) Northern Illinois 1998 190 269 2 .414 0 0 1963 Western Michigan Bowling Green (Overall) Akron 1993 186 305 0 .379 0 1 1964 Kent State 2003 Ball State (West) Buffalo 2001 67 190 0 .261 0 0 Ohio Kent State (East) 1965 Ohio Kent State (Overall) 1966 Western Michigan 2004 Central Michigan (West) Schools No Longer In MAC 1967 Western Michigan Miami (East) School Years W L T Pct. -

(October 3, 2009) October 3, 2009 Page 2 of 38

October 3, 2009 Page 1 of 38 Clips (October 3, 2009) October 3, 2009 Page 2 of 38 From the Los Angeles Times ANGELS 5, OAKLAND 2 Jered Weaver sharp, Kevin Jepsen shaky in Angels victory Weaver throws five shutout innings with five strikeouts, but Jepsen gives up two runs in the ninth inning. By Mike DiGiovanna October 3, 2009 Jered Weaver's spark plugs, air filter and brake fluid look fine. The right-hander looked sharp in his final tuneup for the playoffs Friday night, throwing five shutout innings with five strikeouts and no walks in the Angels' 5-2 victory over the Oakland Athletics. But the check-engine light came on for setup man Kevin Jepsen, who suffered his second shaky outing in seven days, giving up singles to three of the four batters he faced and two runs in the ninth inning. "I feel like I'm out there trying to work on things instead of doing what I normally do, which is go after guys and let it all hang out," Jepsen said. "My velocity is fine, my slider is good, and I'm throwing strikes. I'm just lacking that go-after-them mentality." Jepsen, who could play a vital role in the American League division series against the Boston Red Sox, gave up four runs and three hits to Oakland on Sept. 26 in Anaheim but threw hitless innings in his last two outings. But after Friday night's rocky outing, the right-hander will have one more appearance Sunday to straighten himself out. -

King Loses Bids for Acquittal, New Trial RIVERHAWKS MEET the BRUINS

92 / 59 RIVERHAWKS MEET THE BRUINS FOR THE FIRST TIME SEE SPORTS 1 Mostly sunny. Business 4 A&B WATER APPEAL >>> A&B Irrigation District water call case goes to district court, MAIN 3 WEDNESDAY 75 CENTS September 2, 2009 MagicValley.com For Magic Valley schools, higher King loses bids nutrition standards begin for acquittal, new trial Judge: Jury properly convicted feedlot owner of illegal aquifer injections A BETTER By Nate Poppino questioning whether there A BETTER Times-News writer really was federal jurisdic- tion, if the jury was preju- A Burley man’s attempt to diced and other issues. But seek an acquittal and new in a decision filed Saturday trial on charges of illegal and following a hearing in injection into an under- Boise last month, Winmill ground aquifer has been rebuffed all their arguments rebuffed by a federal judge. and wrote that the jury had By Ben Botkin But attorneys for Cory properly found King guilty. Times-News writer BBALALANCEANCE King, co-owner of the King’s attorneys, David 16,000-acre Double C Lombardi and Larry Farms,said they plan to now Westberg, pledged in a appeal the case to the 9th statement on Tuesday to U.S. Circuit Court of continue to fight the con- Hold the salt, choose the with school districts Appeals. viction. whole grain and cut out the in January to prepare A jury this spring found “The denial of King’s high-fat foods. them for the changes. King guilty of four counts of motion for acquittal and for That’s the mantra in public Among Magic Valley injecting fluids into the new trial has no impact … school cafeterias as classes school districts, some aquifer without a permit on the fundamental lack of begin this fall.