An Integrated Approach to Music and the Language Arts for the Sixth Grade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I Thank You For

©studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I thank you for StudentSavvy © 2016 downloading! Thank you for downloading StudentSavvy’s Music Around the World Unit! If you have any questions regarding this product, please email me at [email protected] Be sure to stay updated and follow for the latest freebies and giveaways! studentsavvyontpt.blogspot.com www.facebook.com/studentsavvy www.pinterest.com/studentsavvy wwww.teacherspayteachers.com/store/studentsavvy clipart by EduClips and IROM BOOK http://www.hm.h555.net/~irom/musical_instruments/ Don’t have a QR Code Reader? That’s okay! Here are the URL links to all the video clips in the unit! Music of Spain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7C8MdtnIHg Music of Japan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OA8HFUNfIk Music of Africa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4g19eRur0v0 Music of Italy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3FOjDnNPHw Music of India: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQ2Yr14Y2e0 Music of Russia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EEiujug_Zcs Music of France: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ge46oJju-JE Music of Brazil: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQLvGghaDbE ©StudentSavvy2016 Don’t leave out these countries in your music study! Click here to study the music of Mexico, China, the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, USA, Hawaii, and the U.K. You may also enjoy these related resources: Music Around the WorLd Table Of Contents Overview of Musical Instrument Categories…………………6 Music of Japan – Read and Learn……………………………………7 Music of Japan – What I learned – Recall.……………………..8 Explore -

Here's What's Happening at AAA in 2013

AMERICAN ACCORDIONISTS’ ASSOCIATION Newsletter A bi-monthly publication of the American Accordionists’ Association JANUARY 2013 From the Editor Here’s What’s Welcome to the January 2013 edition of the AAA Newsletter. As we begin the New Year, it is already shaping up to be an exciting 12 months, full of spectacular accordion events anchored by our own organization’s 75th An- Happening at niversary to be celebrated in New York City in August. My sincere thanks go to our AAA President Linda Reed for her kind assistance in AAA in 2013 the production of this bi-monthly Newsletter which is now celebrating its first an- niversary! I would also like to extend a special thank you to my fellow Board of Director Rita David- son for helping gather and research the News articles, and to all the members who have been able to MARCH 16, 2013 submit items for publication. Coupe Mondiale Items for the March Newsletter can be sent to me at [email protected]. Please include qualifying categories. ‘AAA Newsletter’ in the subject box, so that none of the items are missed when they come in. Text See article on this page should be sent within the e-mail or as a Word .doc (not docx) attachment. Pictures should be sent as a high quality .jpg or similar image file, and the larger the file size the better. We can always MARCH 17, 2013 reduce/crop the picture if necessary, however we are unable to increase the quality from smaller pic- 2:00 pm tures. The deadline for the March 2013 edition will be the 15th of February. -

Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian Art Scene: How to Become a Brazilian Musician*

1 Mana vol.1 no.se Rio de Janeiro Oct. 2006 Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian art scene: how to become a Brazilian musician* Paulo Renato Guérios Master’s in Social Anthropology at PPGAS/Museu Nacional/UFRJ, currently a doctoral student at the same institution ABSTRACT This article discusses how the flux of cultural productions between centre and periphery works, taking as an example the field of music production in France and Brazil in the 1920s. The life trajectories of Jean Cocteau, French poet and painter, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian composer, are taken as the main reference points for the discussion. The article concludes that social actors from the periphery tend themselves to accept the opinions and judgements of the social actors from the centre, taking for granted their definitions concerning the criteria that validate their productions. Key words: Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazilian Music, National Culture, Cultural Flows In July 1923, the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos arrived in Paris as a complete unknown. Some five years had passed since his first large-scale concert in Brazil; Villa-Lobos journeyed to Europe with the intention of publicizing his musical output. His entry into the Parisian art world took place through the group of Brazilian modernist painters and writers he had encountered in 1922, immediately before the Modern Art Week in São Paulo. Following his arrival, the composer was invited to a lunch in the studio of the painter Tarsila do Amaral where he met up with, among others, the poet Sérgio Milliet, the pianist João de Souza Lima, the writer Oswald de Andrade and, among the Parisians, the poet Blaise Cendrars, the musician Erik Satie and the poet and painter Jean Cocteau. -

Folklore______Mmihhhhihhflhi Box 19114,20Th Street Station, W Ashington, DC 20036

Ibe Folklore_______ MMIHHHHIHHflHi Box 19114,20th Street Station, W ashington, DC 20036 j UNBBIHTHI VOLUM E X V I I , NO. 8 APRIL 1981 PHONE (703) 281-2228 Nancy Schatz, Ed it o r Roy Harris Featured in April 10 Program Our April program w ill feature folksinger Roy Harris, Roy, who comes from Nottingham, England, is one of the finest sing ers of traditional songs and ballads. His repertoire is about 80# traditional song with the rest being a mixture of contem porary material, parodies, music hall numbers, even an occa sional popular song from the 1930*s. A ll are presented with a warm, sometimes humorous st yle t h a t 's a l l Royf s own. Roy has been singing full-tim e since 196^ in folk clubs a ll over Europe, Canada, and the United States, He has served as director of the National Folk Festival in Loughborough, Eng land, for four years. He founded the Nottingham tradition al Music Club, He has six solo albums, five of them on the Topic label and one on F e lls id e . The program begins at 8i30 p.m., Friday, April 10, The place* the Washington Ethical Society auditorium, 7750 16th St., N.W. (at Kalmia Rd.) Admission is free to FSGW members, $2 for non-members. Come early to be sure of getting a seat. Battlefield Band to Perform April 18 Battlefield Band can best be described as a high-energy Scottish band. They have just completed their sixth album (Horae Is Where the Van Is, for the Flying Fish label). -

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker July 8-15, and July 15-22 Connecticut College, New London CT Music of France and the Low Countries Largest recorder program in U.S. Expanded vocal programs Renaissance reeds and brass New London Assembly Festival Concert Series Historical Dance Viol Excelsior www.amherstearlymusic.org Amherst Early Music Festival 2018 Week 1: July 8-15 Week 2: July 15-22 Voice, recorder, viol, violin, cello, lute, Voice, recorder, viol, Renaissance reeds Renaissance reeds, flute, oboe, bassoon, and brass, flute, harpsichord, frame drum, harpsichord, historical dance early notation, New London Assembly Special Auditioned Programs Special Auditioned Programs (see website) (see website) Baroque Academy & Opera Roman de Fauvel Medieval Project Advanced Recorder Intensive Ensemble Singing Intensive Choral Workshop Virtuoso Recorder Seminar AMHERST EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL FACULTY CENTRAL PROGRAM The Central Program is our largest and most flexible program, with over 100 students each week. RECORDER VIOL AND VIELLE BAROQUE BASSOON* Tom Beets** Nathan Bontrager Wouter Verschuren It offers a wide variety of classes for most early instruments, voice, and historical dance. Play in a Letitia Berlin Sarah Cunningham* PERCUSSION** consort, sing music by a favorite composer, read from early notation, dance a minuet, or begin a Frances Blaker Shira Kammen** Glen Velez** new instrument. Questions? Call us at (781)488-3337. Check www.amherstearlymusic.org for Deborah Booth* Heather Miller Lardin* Karen Cook** Loren Ludwig VOICE AND THEATER a full list of classes by May 15. Saskia Coolen* Paolo Pandolfo* Benjamin Bagby** Maria Diez-Canedo* John Mark Rozendaal** Michael Barrett** New to the Festival? Fear not! Our open and inviting atmosphere will make you feel at home Eric Haas* Mary Springfels** Stephen Biegner* right away. -

Andean Music, the Left and Pan-Americanism: the Early History

Andean Music, the Left, and Pan-Latin Americanism: The Early History1 Fernando Rios (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) In late 1967, future Nueva Canción (“New Song”) superstars Quilapayún debuted in Paris amid news of Che Guevara’s capture in Bolivia. The ensemble arrived in France with little fanfare. Quilapayún was not well-known at this time in Europe or even back home in Chile, but nonetheless the ensemble enjoyed a favorable reception in the French capital. Remembering their Paris debut, Quilapayún member Carrasco Pirard noted that “Latin American folklore was already well-known among French [university] students” by 1967 and that “our synthesis of kena and revolution had much success among our French friends who shared our political aspirations, wore beards, admired the Cuban Revolution and plotted against international capitalism” (Carrasco Pirard 1988: 124-125, my emphases). Six years later, General Augusto Pinochet’s bloody military coup marked the beginning of Quilapayún’s fifteen-year European exile along with that of fellow Nueva Canción exponents Inti-Illimani. With a pan-Latin Americanist repertory that prominently featured Andean genres and instruments, Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani were ever-present headliners at Leftist and anti-imperialist solidarity events worldwide throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Consequently both Chilean ensembles played an important role in the transnational diffusion of Andean folkloric music and contributed to its widespread association with Leftist politics. But, as Carrasco Pirard’s comment suggests, Andean folkloric music was popular in Europe before Pinochet’s coup exiled Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani in 1973, and by this time Andean music was already associated with the Left in the Old World. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

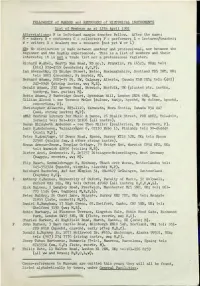

FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESTORERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS List of Members As at 12Th April 1981 Abbreviations: F in Left-Hand Margin Denotes Fellow

FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESTORERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS List of Members as at 12th April 1981 Abbreviations: F in left-hand margin denotes Fellow. After the name: M - maker; R - restorer; C - collector; P - performer; L - lecturer/teacher; W - writer; D - dealer; res - research (not yet W or L) NB: No distinction is made between amateur and professional, nor between the beginner and the highly experienced. This is a list of members and their interests; it is not a trade list nor a professional register. Richard W.Abel, Beatty Run Road, RD no.5, Franklin, PA 16525, USA; tel: (814) 574-4H9 (woodwind; R,C,P). Ian Abernethy, 21 Bridge Street, Kelso, Roxburghshire, Scotland TD5 7HT, UK; tel: 5805 (recorder, P; keybds, M). Bernard Adams, 2025-55 St. SW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T5E 2X5; tel: (405) 242-8946 (string instrs, ww; M,R). Gerald Adams, 252 Queens Road, Norwich, Norfolk, UK (plucked str. instrs, hurdy-g, bar. guitar; M). Robin Adams, 2 Tunbridge Court, Sydenham Hill, London SE26 6RR, UK. Gilliam Alcock - see Terence McGee (dulcmr, banjo, hpschd, M; dulcmr, hpschd, concertina, P). Christopher Allworth, RR5-1110, Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada B5A 4A7 (med. string instrs; M,P). AMLI Central Library for Music & Dance, 26 Bialik Street, POB 4882, Tel-Aviv, Israel; tel: Tel-Aviv 58106 (all instrs). Susan Elizabeth Andersen - see Theo Miller (psalteries, M; recorders, P). Lars H.Andersson, Vaisalavagen 8, 02150 Esbo 15, Finland; tel: 9O-46444O (viol; M,P). Peter B.Armitage, 52 Downs Road, Epsom, Surrey KT18 5JN, UK; tel: Epsom 22560 (violin fam. & other string instrs). -

Dialogues Between a Violin and a Body

Kurs: AA1022 Examensarbete master, folkmusik 30 hp 2021 Konstnärlig masterexamen i musik Institutionen för folkmusik Handlare: Olof Misgeld Coline Genet Dialogues between a violin and a body How to be a dancing musician on stage ? Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt arbete Inspelning av det självständiga, konstnärliga arbetet finns dokumenterat i det tryckta exemplaret av denna text på KMH:s bibliotek . Contents Abstract . .3 PREFACE . .4 1 Introduction . .5 2 Background and concepts . .6 2.1 Performances . .6 2.2 Master and doctoral thesis in artistic research . .7 2.3 Other inspiring artists . .7 2.4 Scientific works . .8 2.5 Concepts . .9 3 Chapter 1: Discovery, dialogue . 14 3.1 Material - The French bourrée ..................... 14 3.2 Construction of the performance . 15 3.3 Space and creativity . 16 4 Chapter 2: Freedom, improvisation . 17 4.1 Upstream work for dance improvisation . 17 4.2 Construction of the performance . 19 4.3 Borders of folk dance and music . 20 5 Chapter 3: Technique, precision, understanding . 21 5.1 Dance meter vs. musical meter . 21 5.1.1 Method . 21 5.1.2 Waltz styles . 22 5.1.3 Polyrhythmic layers: The case of the bourrée . 24 5.2 Dancing and playing at the same time . 26 5.2.1 Common posture . 27 5.2.2 Tune the different meters up . 28 5.2.3 Exercises . 29 5.3 Results . 30 Conclusion . 31 Bibliography 32 References . 33 Appendices . 34 1 The Dancing Musicians - John. B. Vallely 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank Olof Misgeld and Ellika Frisell for supervising this project, inspiring and supporting -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Texas Arly Music Project Daniel Johnson, Artistic Director E

TEXAS ARLY MUSIC PROJECT DANIEL JOHNSON, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR E It’s About Time: Companions (Arrangements & Added Polyphony by D. Johnson, except as noted) Music Direction Daniel Johnson Producers Meredith Ruduski & Daniel Johnson Story & Script Daniel Johnson with Meredith Ruduski Stage Director Phil Groeschel Choreography & Movement Toni Bravo Lighting Christopher Brockett & Wendy Brockett Stage manager Jacob Primeaux Supertitles Ethan Thyssen ACT I OVERTURE ❦ SCENE 1: ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS ... THERE WAS ... AND YET THERE WAS NOT IN A DREAMSCAPE ❦ SCENE 2: AN IBERIAN WEDDING GATHERING, MARCH 31, 1492 THE DEPORTATION ❦ INTERMISSION ❦ ACT II OVERTURE ❦ SCENE 1: PROMENADE INTERNATIONAL A PLEASING MELANCHOLY ❦ SCENE 2: CAFÉ DES AMANTS: FRANCE ❦ SCENE 3: ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS ... THERE WAS ... WASN’T THERE? EPILOGUE TEXAS EARLY MUSIC PROJECT IT’S ABOUT TIME: COMPANIONS Special Guests: Ryland Angel, tenor & alto Toni Bravo, choreographer & dancer Jordan Moser, dancer Mary Springfels, treble viol Peter Walker, bass The Singers (Featured Soloists ***) Erin Calata, mezzo-soprano *** Robbie LaBanca, tenor *** Cristian Cantu, tenor Sean Lee, alto *** Cayla Cardiff, soprano *** David Lopez, tenor Heath Dill, bass Hannah McGinty, soprano Rebecca Frazier-Smith, alto Gitanjali Mathur, soprano *** Jenny Houghton, soprano *** Susan Richter, alto Daniel Johnson, tenor *** Meredith Ruduski, soprano *** Eric Johnson, bass Jenifer Thyssen, soprano *** Jeffrey Jones-Ragona, tenor *** Shari Alise Wilson, soprano *** Morgan Kramer, bass Gil Zilkha, bass *** Sara Schneider, reader The Orchestra Elaine Barber, harp Josh Peters, oud & percussion Bruce Colson, Baroque violin Stephanie Raby, tenor viol & Baroque violin Victor Eijkhout, recorders Susan Richter, recorders Therese Honey, harp John Walters, bass viol, vielle, & mandolin Scott Horton, archlute, vihuela, & guitar Shari Alise Wilson, piano Jane Leggiero, bass viol Please visit www.early-music.org to read the biographies of TEMP artists. -

Dissertation Final Submission Andy Hillhouse

TOURING AS SOCIAL PRACTICE: TRANSNATIONAL FESTIVALS, PERSONALIZED NETWORKS, AND NEW FOLK MUSIC SENSIBILITIES by Andrew Neil Hillhouse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew Neil Hillhouse (2013) ABSTRACT Touring as Social Practice: Transnational Festivals, Personalized Networks, and New Folk Music Sensibilities Andrew Neil Hillhouse Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 The aim of this dissertation is to contribute to an understanding of the changing relationship between collectivist ideals and individualism within dispersed, transnational, and heterogeneous cultural spaces. I focus on musicians working in professional folk music, a field that has strong, historic associations with collectivism. This field consists of folk festivals, music camps, and other venues at which musicians from a range of countries, affiliated with broad labels such as ‘Celtic,’ ‘Nordic,’ ‘bluegrass,’ or ‘fiddle music,’ interact. Various collaborative connections emerge from such encounters, creating socio-musical networks that cross boundaries of genre, region, and nation. These interactions create a social space that has received little attention in ethnomusicology. While there is an emerging body of literature devoted to specific folk festivals in the context of globalization, few studies have examined the relationship between the transnational character of this circuit and the changing sensibilities, music, and social networks of particular musicians who make a living on it. To this end, I examine the career trajectories of three interrelated musicians who have worked in folk music: the late Canadian fiddler Oliver Schroer (1956-2008), the ii Irish flute player Nuala Kennedy, and the Italian organetto player Filippo Gambetta.