The Bbc Trust Impartiality Review Business Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Wars in Ireland

new masses: ireland and armenia In this number, nlr’s ‘New Masses, New Media’ series examines the character of the recent protests in Armenia and Ireland, both sparked by price hikes for basic goods: electricity in one case, water in the other. Comparable in population—4.5m and 3m, respectively—Ireland as a whole is three times the size of Armenia. Historically, both have been shaped by their location between two imperial powers: Britain and America, Turkey and Russia. If there is an eerie parallel in the numbers estimated to have perished in the Irish Famine and the Armenian Genocide—between 800,000 and a million—the deliberately exterminationist policies of the Young Turks are of a different order of political and moral malignity to the laissez-faire arrogance of English colonialism. A mark of these dark pasts, in both cases the diaspora significantly outweighs the domestic population. In recent times, both countries have figured on the margin of larger economic unions, the eu and cis; as a result, their trajectories in the 1990s were diametrically opposed. Armenia had been a high-end industrial hub within the Soviet Union, specializing in machine goods and electronic products. Already hit by the 1988 earthquake, its economy suffered one of the sharpest contractions of the former ussr as industrial disruption was exacerbated by war and blockade. From $2.25bn in 1990, Armenian gdp dropped to $1.2bn in 1993; it did not recover to its Soviet-era level until 2002. By that time, the population had fallen by 15 per cent, from 3.54m in 1990 to barely 3m; by 2013 it was down to 2.97m. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of Journal Stories, Plus Any Other News About the Company That Has Appeared in the National A

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of journal stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. A total of 21 journals were picked up in the media last week (1-7 April) - our highlights include: ● A study in The BMJ finding that routine HPV vaccination has led to a dramatic reduction in cervical disease among young women in Scotland was covered extensively, including BBC Radio 4 Today, The Guardian and Cosmopolitan. ● Research in Tobacco control suggesting that vaping has not re-normalised tobacco smoking among teens was picked up by The Independent, The Irish Times and The South China Morning Post ● A paper in the Archives of Disease in Childhood on misleading health claims on kids’ snacks packaging was picked up by The Times, BBC News and The Daily Telegraph. PRESS RELEASES BMJ | The BMJ Thorax | Tobacco Control Archives of Disease in Childhood | Vet Record EXTERNAL PRESS RELEASES The BMJ OTHER COVERAGE The BMJ | Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases BMJ Case Reports | BMJ Global Health BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health | BMJ Open BMJ Open Quality | BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine British Journal of Sports Medicine | Heart Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health | Journal of Investigative Medicine Journal of Medical Ethics | Journal of Medical Genetics Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps | Occupational & Environmental Medicine B MJ New Editor-in-Chief for BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine journal InPublishing 02/04/2019 (PR) Health Education England chooses BMJ Best Practice InPublishing 03/04/19 (PR) Antiseptics and Disinfectants Market Size Worth $27.99 Billion by 2026: Grand View Research, Inc. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

1 HOSSEIN ASKARI International Business Department George

1 HOSSEIN ASKARI International Business Department George Washington University Washington DC 20052 Tel: (202) 994-0847 Fax: (202) 994-7422 Homepage: http://hossein-askari.com/ Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) 1970 Ph.D. Economics (International Finance and Trade) 1967 Sloan School of Management 1966 B.S. Civil Engineering TEACHING POSITIONS: CURRENT Iran Professor of International Business and International Affairs, George Washington University PREVIOUS Professor of International Business and International Affairs, George Washington University (since 1982), Professor and Associate Professor of International Business and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Texas at Austin (1975-1981), Associate Professor of Economics, Wayne State University (1973- 1975), Assistant Professor of Economics, Tufts University (1969-1973), Instructor of Economics, MIT (1968-1969), and Adjunct Professor: School For Advanced International Studies (Johns Hopkins) and Clark University ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS: 1998-2000 Faculty Director, Institute for Global Management and Research, The George Washington University 1995-1998 Director, Institute for Global Management and Research, The George Washington University 1992-1997 Chairman, Department of International Business, The George Washington University 2 OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: CONSULTING: OECD, World Bank, IFC, APDF, IFU, United Nations, Petroleum Finance Company, Bechtel, First National Bank of Chicago, Eastman (Kodak) Chemical, Litton Industries, The Royal -

Management Discussion and Analysis — Business Review

Management Discussion and Analysis — Business Review Operating income for each line of business of the Group is set forth in the following table: Unit: RMB million, except percentages 2019 2018 Items Amount % of total Amount % of total Commercial banking business 497,424 90.44% 462,355 91.77% Including: Corporate banking business 221,123 40.21% 211,365 41.96% Personal banking business 186,744 33.95% 173,531 34.44% Treasury operations 89,557 16.28% 77,459 15.37% Investment banking and insurance 35,226 6.40% 25,524 5.07% Others and elimination 17,360 3.16% 15,927 3.16% Total 550,010 100.00% 503,806 100.00% A detailed review of the Group’s principal deposits and loans is summarised in the following table: Unit: RMB million As at As at As at Items 31 December 2019 31 December 2018 31 December 2017 Corporate deposits Chinese mainland: RMB 6,027,076 5,884,433 5,495,494 Foreign currency 544,829 453,815 436,458 Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan and other countries and regions 1,729,564 1,594,165 1,451,822 Subtotal 8,301,469 7,932,413 7,383,774 Personal deposits Chinese mainland: RMB 5,544,204 5,026,322 4,551,168 Foreign currency 288,793 302,256 310,253 Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan and other countries and regions 1,156,651 1,093,892 969,807 Subtotal 6,989,648 6,422,470 5,831,228 Corporate loans Chinese mainland: RMB 5,591,228 5,057,654 4,761,874 Foreign currency 259,463 280,878 338,379 Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan and other countries and regions 2,135,689 2,009,066 1,872,448 Subtotal 7,986,380 7,347,598 6,972,701 Personal loans Chinese mainland: RMB 4,450,464 3,933,840 -

Sorry We Missed

Tuesday 30.05.17 Tuesday SORRY WE MISSED YOU →→ We called at: Reason forr non-delivery:non-delivnon delivvery:ery: Comment: Item: Depot:Depot Ref:: Trump v Underwood Who said it? Restaurant rules Lisa Markwell Ask Hadley Cute clothes ‘Squeal like a pig!’ Making Deliverance 12A Shortcuts Never order the specials: one of Gordon Ramsay’s tips for a good meal Restaurants Check the loos The golden rules of eating out and snack before you go Call, don’t click Places that show “no tables available” online may have ordon Ramsay has a new something if you take the Complain, complain, complain TV show to promote , so G trouble to telephone. They Nobody wants to leave dinner he’s effi ng and blinding will know about cancellations with a sour taste in their mouth and pronouncing like his career straight away, and if you … If the food is lousy or the depend s on it . Yesterday, we engage with the person at the table judders in time with the learn ed his rules for eating out: restaurant, you might get a dishwasher, tell them. A restau- never order the specials, haggle note on the booking that means rateur would rather fi over wine and be wary of the you’ll get a nicer table. and there (with a free xdessert, it then waiter’s boasts, such as “our or some wine, or money off famous lasagne”. He also asks for Look at the loos than have someone smile, pay a table for three when there are ) Like Bourdain, I wouldn’t the bill and then go home and only two dining – or does he mean eat somewhere that doesn’t Have lunch, not dinner savage them on TripAdvisor. -

Board Meeting May Tuesday 23 May 2017

Board Meeting May Tuesday 23 May 2017 10am – 3pm Meeting Time: 10.00am - 1.00pm Board Only Working Lunch: 1.00pm - 3.00pm Venue: Ergon House, London Quorum: 7 non-executive Board members 1. Apologies Emma Howard Boyd 2. Declarations of Interest Emma Howard Boyd 10.00am 5 mins 3. Minutes of the Board meeting held on 25 April Emma Howard Boyd 2017 and matters arising 4. Chief Executive's update James Bevan 10.05am 20 mins 5. Committee meetings – oral updates and forward 10.25am look 30 mins • Audit and Risk Assurance Karen Burrows • Pensions Clive Elphick • FCRM Lynne Frostick • E&B Gill Weeks • Remuneration Committee Emma Howard Boyd 7. Strategic Review of Charges Harvey Bradshaw 10.55am For information 20 mins 8. Committee on Standards in Public Life, 7 Peter Kellett 11.15am principles of public life in regulation 30 mins For information 9. Communications Forward Look Mark Funnell 11.45am For information 15 mins 10. Finance Report and update on the year Bob Branson 12.00pm including the Draft Annual Report and Accounts 10 mins For information/delegation 11. Schemes of Delegation Bob Branson 12.10pm For approval Clive Elphick 5 mins 12. SE IDB Annual report and accounts Toby Willison 12.15pm For approval 5 mins 6. Governance/Transformation and EU briefing James Bevan 12.20pm For information Betsy Bassis 30 mins 13. AOB and date of next meeting – Tuesday 27/28 Emma Howard Boyd 12.50pm June 2017, Thames Barrier 5 mins 14. Review of meeting Emma Howard Boyd 12.55pm 5 mins Board only working Lunch in the Chairs office, a Emma Howard Boyd 1.00pm continuation of discussions from the meeting. -

Contact Information for Non-USC Activities

6/16/17 CURRICULUM VITAE JOEL W. HAY, PhD PERSONAL INFORMATION Business/Mail Address Professor of Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy & Professor of Health Policy and Economics University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics University Park Campus, Verna & Peter Dauterive Hall (VPD 214-L) 635 Downey Way Los Angeles, CA 90089-3333 USA Business Telephone Office: (818) 338-5433 Assistant: (213) 821-7940 Fax: (213) 740-3460 (ATTN: Joel Hay) E-Mail [email protected] USC Websites : http://healthpolicy.usc.edu/ListItem.aspx?ID=4 http://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/faculty/profile/?id=374 Graduate Program Website : http://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/programs/pep/ Schaeffer Center Street Address 635 Downey Way Los Angeles, CA 90089-3333 USA (Deliveries, e.g. Fedex, UPS) Main Phone/Front Desk: (213) 821-7940 J Hay Office: (213) 821-8160 Fax: (213) 740-3460 (ATTN: Samantha) http://healthpolicy.usc.edu Contact Information for Non-USC Activities Joel W. Hay, PhD 22101 Dardenne St. Calabasas, CA 91302 818-338-5433 [email protected] Joel W. Hay, Ph.D. -- C.V. -2- 6/16/17 EDUCATION 1974 B.A. (Summa cum laude), Economics, Amherst College 1975 M.A., Economics, Yale University 1976 M.Phil., Economics, Yale University 1980 Ph.D., Economics, Yale University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE March 2009 – Present Full Professor (with tenure), Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy; School of Pharmacy Professor (by courtesy), Department of Economics; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. September 2009-Present Full Professor, Health Economics and Policy Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 1992 – 2009 Associate Professor (with tenure), Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy; School of Pharmacy. -

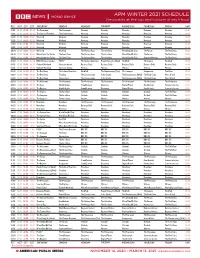

APM WINTER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the Top and Bottom of Each Hour

APM WINTER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PST MST CST EST SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 The Cultural Frontline The Conversation Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:30 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 08:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 When Katty Met Carlos The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 08:30 00:50 01:50 02:50 03:50 When Katty Met Carlos The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club Sporting Witness The Real Story 08:50 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 BBC OS Conversations FOOC* The Climate Question People Fixing the World HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 09:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 Outlook Weekend Science in Action Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 09:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 Outlook Weekend Science in Action Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 09:50 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 The Real Story The Cultural Frontline HardTalk The Documentary -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Factual Autumn Highlights 2004

FACTUAL AUTUMN HIGHLIGHTS 2004 ONE NIGHT IN BHOPAL In the early hours of 3 December 1984, a cloud of poisonous gas escaped from a pesticide plant in the Indian city of Bhopal. It drifted into the sleeping city and, within a few hours, thousands of people had died and many thousands more were left crippled for life. One Night In Bhopal reveals how and why an American-owned chemical factory that was meant to bring prosperity to the people of an Indian city, instead brought death and destruction. By mixing drama, documentary, graphics and archive material, the programme gives an extraordinary insight into the world’s worst industrial disaster. ©2004 Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos, All Rights Reserved 18 FAT NATION - THE BIG CHALLENGE BBC CHILDREN IN NEED SLEEP The BBC is launching a major new Each week challenges are set for Pudsey Bear is getting ready to party. This year promises to be an extra Counting sheep could be a thing of initiative across television, online, the residents and those watching special BBC Children In Need Appeal because it marks the 25th anniversary the past, as BBC One launches the radio and interactive services to at home can join in by accessing of the UK’s best-loved charity telethon. The campaign kicks off in September UK’s biggest-ever sleep experiment help Britain take simple steps interactive television, SMS and and climaxes in a star-studded night on BBC One. It will once again unite the and invites the population to take towards living a healthier life. bbc.co.ukHi BBC across TV, radio and online activity as Terry Wogan and Gaby Roslin are part in an extensive sleep survey. -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side.