Economic Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations From

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Human Biology Volume 85 Issue 1 Special Issue on Revisiting the "Negrito" Article 9 Hypothesis 2013 Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations from Luzon: Comparison of Male and Female Effective Population Sizes and Differential Integration of Immigrants into Aeta and Agta Communities E Heyer EcoAnthropologie et Ethnobiologie, MNHN, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France, [email protected] M Georges EcoAnthropologie et Ethnobiologie, MNHN, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France M Pachner Andaman and Nicobar Association, Liestal, Switzerland P Endicott EcoAnthropologie et Ethnobiologie, MNHN, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Recommended Citation Heyer, E; Georges, M; Pachner, M; and Endicott, P (2013) "Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations from Luzon: Comparison of Male and Female Effective Population Sizes and Differential Integration of Immigrants into Aeta and Agta Communities," Human Biology: Vol. 85: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/9 Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations from Luzon: Comparison of Male and Female Effective Population Sizes and Differential Integration of Immigrants into Aeta and Agta Communities Abstract Genetic data corresponding to four negrito populations (two Aeta and two Agta; n = 120) from the Luzon region of the Philippines have been analyzed. These data comprise mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) hypervariable segment 1 haplotypes and haplogroups, Y-chromosome haplogroups and short tandem repeats (STRs), autosomal STRs, and X-chromosome STRs. -

In Search of Language Contact Between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: the Languages of South Andaman1

Acta Orientalia 2011: 72, 1–40. Copyright © 2011 Printed in India – all rights reserved ACTA ORIENTALIA ISSN 0001-6483 In search of language contact between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: The languages of South Andaman1 Anvita Abbi and Pramod Kumar Cairns Institute, Cairns, Australia & Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Abstract The paper brings forth a preliminary report on the comparative data available on the extinct language Aka-Bea (Man 1923) and the endangered language Jarawa spoken in the south and the central parts of the Andaman Islands. Speakers of Aka-Bea, a South Andaman language of the Great Andamanese family and the speakers of Jarawa, the language of a distinct language family (Abbi 2006, 2009, Blevins 2008) lived adjacent to each other, i.e. in the southern region of the Great Andaman Islands in the past. Both had been hunter-gatherers and never had any contact with each other (Portman 1899, 1990). The Jarawas have been known for living in isolation for thousands of years, coming in contact with the outside world only recently in 1998. It is, then surprising to discover traces of some language-contact in the past between the two communities. Not a large database, but a few examples of lexical similarities between Aka-Bea and Jarawa are 1 The initial version of this paper was presented in The First Conference on ASJP and Language Prehistory (ALP-I), on 18 September 2010, Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany. We thank Alexandra Aikhnevald for helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper. 2 Anvita Abbi & Pramod Kumar investigated here. -

Unique Origin of Andaman Islanders: Insight from Autosomal Loci

J Hum Genet (2006) 51:800–804 DOI 10.1007/s10038-006-0026-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Unique origin of Andaman Islanders: insight from autosomal loci K. Thangaraj Æ G. Chaubey Æ A. G. Reddy Æ V. K. Singh Æ L. Singh Received: 9 April 2006 / Accepted: 1 June 2006 / Published online: 19 August 2006 Ó The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Our mtDNA and Y chromosome studies Introduction lead to the conclusion that the Andamanese ‘‘Negrito’’ mtDNA lineages have survived in the Andaman Is- The ‘‘Negrito’’ populations found scattered in parts of lands in complete genetic isolation from other South southern India, the Andaman Islands, Malaysia and the and Southeast Asian populations since the initial set- Philippines are considered to be the relic of early tlement of the region by the out-of-Africa migration. In modern humans and hence assume considerable order to obtain a robust reconstruction of the evolu- anthropological and genetic importance. Their gene tionary history of the Andamanese, we carried out a pool is slowly disappearing either due to assimilation study on the three aboriginal populations, namely, the with adjoining populations, as in the case of the Se- Great Andamanese, Onge and Nicobarese, using mang of Malaysia and Aeta of the Philippines, or due autosomal microsatellite markers. The range of alleles to their population collapse, as is evident in the case of (7–31.2) observed in the studied population and het- the aboriginals of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman erozygosity values (0.392–0.857) indicate that the se- and Nicobar Islands are inhabited by six enigmatic lected STR markers are highly polymorphic in all the indigenous tribal populations, of which four have been three populations, and genetic variability within the characterized traditionally as ‘‘Negritos’’ (the Jarawa, populations is significantly high, with a mean gene Onge, Sentinelese and Great Andamanese) and two as diversity of 77%. -

A War-Prone Tribe Migrated out of Africa to Populate the World

A war-prone tribe migrated out of Africa to populate the world. Eduardo Moreno1. 1 CNIO, Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3. Madrid 28029, Spain. Of the tribal hunter gatherers still in existence today, some lead lives of great violence, whereas other groups live in societies with no warfare and very little murder1,2,3,4,5. Here I find that hunter gatherers that belong to mitochondrial haplotypes L0, L1 and L2 do not have a culture of ritualized fights. In contrast to this, almost all L3 derived hunter gatherers have a more belligerent culture that includes ritualized fights such as wrestling, stick fights or headhunting expeditions. This appears to be independent of their environment, because ritualized fights occur in all climates, from the tropics to the arctic. There is also a correlation between mitochondrial haplotypes and warfare propensity or the use of murder and suicide to resolve conflicts. This, in the light of the “recent out of Africa” hypothesis”6,7, suggests that the tribe that left Africa 80.000 years ago performed ritualized fights. In contrast to the more pacific tradition of non-L3 foragers, it may also have had a tendency towards combat. The data implicate that the entire human population outside Africa is descended from only two closely related sub-branches of L3 that practiced ritual fighting and probably had a higher propensity towards warfare and the use of murder for conflict resolution. This may have crucially influenced the subsequent history of the world. There is little evidence for the practice of war before the late Paleolithic3,4. -

The Jarawa of the Andamans

Te Jarawa of the Andamans Rhea John and Harsh Mander* India’s Andaman Islands are home to some of the some scholars describe appropriately as ‘adverse most ancient, and until recently the most isolated, inclusion’.1 Te experience of other Andaman tribes peoples in the world. Today barely a few hundred like the Great Andamanese and the Onge highlight of these peoples survive. Tis report is about one of poignantly and sombrely the many harmful these ancient communities of the Andaman Islands, consequences of such inclusion.2 Te continued the Jarawa, or as they describe themselves, the Ang. dogged resistance of the Sentinelese to any contact with outsiders makes them perhaps the most Until the 1970s, and even to a degree until the isolated people in the world. On the other hand, 1990s, the Jarawa people fercely and ofen violently the early adverse consequences of exposure of the defended their forest homelands, fghting of a Jarawa people to diseases and sexual exploitation diverse range of incursions and ofers of ‘friendly’ by outsiders, suggest that safeguarding many forms contact—by other tribes-people, colonial rulers, of ‘exclusion’ may paradoxically constitute the best convicts brought in from mainland India by the chance for the just and humane ‘inclusion’ of these colonisers, the Japanese occupiers, independent highly vulnerable communities. India’s administration, and mainland communities settled on the islands by the Indian government. Since However, the optimal balance between isolation the 1990s, two of the three main Ang communities and contact with the outside world of such have altered their relationship with the outsider of indigenous communities is something that no many hues, accepting their ‘friendship’ and all that government in the modern world has yet succeeded came with it, including health care support, clothes, in establishing. -

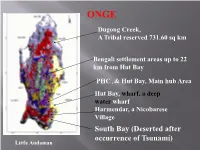

South Bay (Deserted After Occurrence of Tsunami)

ONGE Dugong Creek, A Tribal reserved 731.60 sq km Bengali settlement areas up to 22 km from Hut Bay PHC , & Hut Bay, Main hub Area Hut Bay, wharf, a deep water wharf Harmendar, a Nicobarese Village South Bay (Deserted after occurrence of Tsunami) Little Andaman Little Andaman (LA) Island once was exclusively the abode of the OG until early 1960s OG tribe, settled at Dugong Creek (DC) & South Bay, LA in 1978 Post-Tsunami situation relocated them a little away from DC The geographical isolation of Dugong and South Bay offers a secure resemblance of nomadic pursuits, and the tropical rain forest, ecology, creeks, rivulets, sea etc are conducive to sustain foraging activities throughout the year. Age-wise population Age Male Female Total Sex group) (in years) N % N % N % Ratio 0-10 25 53.19 22 46.81 47 100 880 11-20 11 57.89 08 42.11 19 100 727 21-30 07 53.85 06 46.15 13 100 857 31-40 03 30 07 70 10 100 2333 41-50 03 42.85 04 57.15 07 100 1333 51+ 04 36.36 07 63.64 11 100 1750 53 49.53 54 50.47 107 100 1019 *AAJVS *Till June 2012 Socio-Economic condition of the Onge As semi-nomad forager, hunting & fishing were their fortes, fond of dugong that they hunt on full moon night Being animists, belief on ancestral assistance in various foraging activities Observed adolescent ritual for a month long usually followed by smearing their bodies & hunting as well Body painting with red ochre & white clay common Dead is buried under the large bedstead in the hut, which is then deserted Monogamy stringently adhered to as marriage rules, re-marriage of widow or widower allowable Pre-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Onge settlement deserted Post-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Intrinsic designs, which are usually painted by womenfolk on their loving spouses & on themselves too. -

Stature, Mortality, and Life History Among Indigenous Populations of the Andaman Islands, 1871–1986

713 attainment of stature before agriculture and urbanization cre- Reports ated conditions favoring the reduction of body size (Stini 1975). This argument suggests that larger body size would be characteristic of hunter-gatherers and human populations in Stature, Mortality, and Life History among general due to past selective pressure. Indigenous Populations of the Andaman Several studies have documented negative secular trends in stature (Bogin, Keep, and Edwards 1996; Price 1985; Tobias Islands, 1871–1986 1975, 1985; Torretta et al. 1994). These temporal decreases in J. T. Stock and A. B. Migliano stature demonstrate that a reduction in body size may be found during periods of particular hardship. Few studies have Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, documented long-term changes in body size among hunter- Department of Biological Anthropology, University of gatherers or other nonagricultural societies. When this has Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, United been done, researchers have identified neutral or positive sec- Kingdom ([email protected]). 3 V 09 ular trends (Comuzzie et al. 1995; Pretty et al. 1998; Tobias 1975). While there is significant evidence for small stature among undernourished populations, poor nutrition may not Despite considerable interest in the evolution of small body be the only factor influencing small body size. Differences in size, there is little evidence for changes in body size within growth and age-related stature are likely to have some genetic small-bodied human populations. This study combines an- basis (Martorell 1985). thropometric data from a number of studies of the body size Small-bodied people (pygmies) are often considered to be of Andaman Islanders from 1871 to 1986. -

1 Linguistic Clues to Andamanese Pre-History

Linguistic clues to Andamanese pre-history: Understanding the North-South divide Juliette Blevins Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology ABSTRACT The Andaman Islands, were, until the 19th century, home to numerous hunter-gatherer societies. The ten or so tribes of Great Andamanese spread over the north and central parts of the islands are thought to have spoken related languages, while the Onge, Jangil and Jarawa of the southern parts, including Little Andaman, have been assumed to constitute a distinct linguistic family of 'Ongan' languages. Preliminary reconstruction of Proto-Ongan shows a potential link to Austronesian languages (Blevins 2007). Here, preliminary reconstructions of Proto-Great Andamanese are presented. Two interesting differences characterize the proto-languages of northern vs. southern tribes. First, sea-related terms are easily reconstructable for Proto-Great Andamanese, while the same is not true of Proto-Ongan. Second, where Proto-Ongan shows an Austronesian adstrate, Proto-Great Andamanese includes lexemes which resemble Austroasiatic reconstructions. These linguistic clues suggest distinct prehistoric origins for the two groups. 1. An introduction to languages and peoples of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman Islands are a cluster of over 200 islands in the Bay of Bengal between India and Myanmar (Burma) (see Map 1). [MAP 1 AROUND HERE; COURTESY OF GEORGE WEBER] They were once home to a range of hunter-gatherer societies, who are best known from the descriptions of Man (1883) and Radcliffe-Brown (1922). These writers, along with the Andamanese themselves, split the population of the Andamans into two primary language/culture groups, the 'Great Andaman Group' and the 'Little Andaman Group' (Radcliffe-Brown 1922:11). -

Colonial Practices in the Andaman Islands

For Cileme of course! And for Appa on his seventy fifth. 1 2 DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNOCIDE: COLONIAL PRACTICES IN THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS by Sita Venkateswar Massey University - Palmerston North Aotearoa/New Zealand IWGIA Document No. 111 - Copenhagen 2004 3 DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNOCIDE: COLONIAL PRACTICES IN THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS Author: Sita Venkateswar Copyright: IWGIA 2004 – All Rights Reserved Editing: Christian Erni and Sille Stidsen Cover design, typesetting and maps: Jorge Monrás Proofreading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks/Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISBN: 87-91563-04-6 ISSN: 0105-4503 Distribution in North America: Transaction Publishers 390 Campus Drive / Somerset, New Jersey 08873 www.transactionpub.com INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax: (45) 35 27 05 07 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.iwgia.org 4 This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 5 CONTENTS Map ..............................................................................................................9 Preface ..........................................................................................................10 Prologue: a Sense of Place .......................................................................12 The island ecology ......................................................................................14 The passage to the field site ......................................................................18 -

Discerning the Origins of the Negritos, First Sundaland People: Deep Divergence and Archaic Admixture

GBE Discerning the Origins of the Negritos, First Sundaland People: Deep Divergence and Archaic Admixture Timothy A. Jinam1, Maude E. Phipps2, Farhang Aghakhanian2, Partha P. Majumder3, Francisco Datar4, Mark Stoneking5,HiromiSawai6,NaoNishida6,7, Katsushi Tokunaga6,ShojiKawamura8, Keiichi Omoto9,and Naruya Saitou1,* 1Division of Population Genetics, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan 2Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Sunway City, Selangor, Malaysia 3National Institute of Biomedical Genomics, Kalyani, West Bengal, India 4Department of Anthropology, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, The Philippines 5Department of Evolutionary Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany 6Department of Human Genetics, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Japan 7Department of Hepatic Disease, Research Center for Hepatitis and Immunology, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Chiba, Japan 8Department of Integrated Biosciences, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Japan 9Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Science, The University of Tokyo, Japan *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: July 9, 2017 Abstract Human presence in Southeast Asia dates back to at least 40,000 years ago, when the current islands formed a continental shelf called Sundaland. In the Philippine Islands, Peninsular Malaysia, and Andaman Islands, there exist indigenous groups collectively called Negritos whose ancestry can be traced to the “First Sundaland People.” To understand the relationship between these Negrito groups and their demographic histories, we generated genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism data in the Philippine Negritos and compared them with existing data from other populations. Phylogenetic tree analyses show that Negritos are basal to other East and Southeast Asians, and that they diverged from West Eurasians at least 38,000 years ago. -

Developmental Strategies and Its Impact on an Island's Ecosystem

Developmental Strategies and its Impact on an Island’s Ecosystem and Bio-diversity- A Geographical Appraisal on Little Andaman Island, India Dr. Saswati Roy Assistant Professor Department of Geography Sarsuna College, Calcutta University India Location of Andaman Island in context to the world Map not to scale Why this remote island? • Being sea locked, this island is aloof from the intermingling complexities of the mainland policies. • These commercial policies which were injected on this virgin part-- had an ugly outcome. Uniqueness of the island • This remote Little Andaman Island is selected because of its several uniqueness: 1) This island remained unaltered through mainstream developmental policies till the pre-independence period (1947). 2) Its unique chronological input of developmental strategies since Indian independence. 3) Its unique composition of forest and its rapid depletion. 4) Its complex population structure: Two indigenous tribal communities and rehabilitated mainlanders. 5) Its unique size and location - the southern most part of the South Andaman district • Physiography: Physiography and Climate • Area = 732.8 square km • Highest elevation = 210 meters above mean sea level. • Maximum length = approx 40 km • Maximum width = approx 25 km. • Climatic characteristics: This Island depicts a true tropical climate Highest elevation • regime 210 metres • Mean maximum temperature = 33.3 o C during the month of April • Mean minimum temperature = 19.1 o C during March. • Average annual rainfall = 3000 mm. • The south-west monsoon brings most of the precipitation normally begins in May and ends in October. • Soil: • Soil of this Island are nutritionally poor. • The depth of the soil is very shallow with low Organic matter. -

Intellectual and Cultural Property Rights of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Asia by Michael A

report Intellectual and Cultural Property Rights of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Asia By Michael A. Bengwayan Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non- acknowledges the support of the Community Fund, DFID governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the and of all other organizations and individuals who gave rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and financial and other assistance for this report. Commissioning indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation Editor: Shelina Thawer. Report Editor: Sophie Richmond. and understanding between communities. Our activities are focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and This report has been written by Michael Bengwayan. He outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our acknowledges the use of extracts from ‘Traditional worldwide partner network of organizations which represent knowledge of biodiversity in Asia-Pacific’ by GRAIN and minority and indigenous peoples. Kalpavriksh, October 2002, www.grain.org.publications/tk- asia-2002-en.cfm, and ‘Biotechnology and Indigenous MRG works with over 150 organizations in over 50 countries. Peoples’ by Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Our governing Council, which meets twice a year, has www.twnside.org.sg/title/tokar.htm. members from 10 different countries. MRG has consultative Michael Bengwayan completed his PhD in Environmental status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council Resource Management, and his Masters degree in Rural (ECOSOC), and observer status with the African Commision Development Studies at University College Dublin, Ireland. for Human and Peoples’ Rights. MRG is registered as a He is head of Project PINE TREE, New York, and a journalist charity and a company limited by guarantee under English writing on environmental and indigenous issues.