Unique Origin of Andaman Islanders: Insight from Autosomal Loci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar

Andaman Islands: Development or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar DEVELOPMENT OR DESPOILATION? The Andaman Islands under colonial and postcolonial regimes M.V. KRISHNAKUMAR Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi <[email protected]> Abstract The last quarter of the 19th Century marked an important watershed in the history of the Andaman Islands. The establishment of a penal settlement and an Imperial forestry service, along with other radical changes in the islands’ traditional economy and society, completely transformed the basic pattern of their forest resource use and entire system of forest management. These colonial policies, directly or indirectly, had a drastic impact on the indigenous population and island ecology. This article analyses the sources of environmental change in the Andaman Islands by examining the general ecological impacts of the state initiated development programmes. It also analyses the ‘civilising missions’ and forestry operations undertaken by British colonial administrators as well as the Indian state’s development initiatives under the ‘Five Year Plans’ that followed Indian independence in 1947. Keywords Andaman Islands, forestry, development, environmental change, Andaman tribes Introduction On December 26th 2004 a tsunami triggered by an earthquake off the south east coast of Sumatra swept across the Indian Ocean swamping many low-lying coastal areas and causing death, destruction of properties and infrastructure and despoliation of crops. Amongst those territories worst affected by the surge were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. When Indian prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh visited the islands in the immediate aftermath of the flooding he identified that the project to reconstruct and rehabilitate coastal areas of islands provided the opportunity for a ‘New Andamans’ in which sustainable agriculture and fishery enterprises could exist in harmony with the natural environment. -

The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire*

IRSH 63 (2018), Special Issue, pp. 25–43 doi:10.1017/S0020859018000202 © 2018 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire* C LARE A NDERSON School of History, Politics and International Relations University of Leicester University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article explores the British Empire’s configuration of imprisonment and transportation in the Andaman Islands penal colony. It shows that British governance in the Islands produced new modes of carcerality and coerced migration in which the relocation of convicts, prisoners, and criminal tribes underpinned imperial attempts at political dominance and economic development. The article focuses on the penal transportation of Eurasian convicts, the employment of free Eurasians and Anglo-Indians as convict overseers and administrators, the migration of “volunteer” Indian prisoners from the mainland, the free settlement of Anglo-Indians, and the forced resettlement of the Bhantu “criminal tribe”.It examines the issue from the periphery of British India, thus showing that class, race, and criminality combined to produce penal and social outcomes that were different from those of the imperial mainland. These were related to ideologies of imperial governmentality, including social discipline and penal practice, and the exigencies of political economy. INTRODUCTION Between 1858 and 1939, the British government of India transported around 83,000 Indian and Burmese convicts to the penal colony of the Andamans, an island archipelago situated in the Bay of Bengal (Figure 1). -

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

Arachnozoogeographical Analysis of the Boundary Between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region

Historia naturalis bulgarica, 23: 5-36, 2016 Arachnozoogeographical analysis of the boundary between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region Petar Beron Abstract: This study aims to test how the distribution of various orders of Arachnida follows the classical subdivision of Asia and where the transitional zone between the Eastern Palearctic (Holarctic Kingdom) and the Indomalayan Region (Paleotropic) is situated. This boundary includes Thar Desert, Karakorum, Himalaya, a band in Central China, the line north of Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. The conclusion is that most families of Arachnida (90), excluding most of the representatives of Acari, are common for the Palearctic and Indomalayan Regions. There are no endemic orders or suborders in any of them. Regarding Arach- nida, their distribution does not justify the sharp difference between the two Kingdoms (Paleotropical and Holarctic) in Eastern Eurasia. The transitional zone (Sino-Japanese Realm) of Holt et al. (2013) also does not satisfy the criteria for outlining an area on the same footing as the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms. Key words: Palearctic, Indomalayan, Arachnozoogeography, Arachnida According to the classical subdivision the region’s high mountains and plateaus. In southern Indomalayan Region is formed from the regions in Asia the boundary of the Palearctic is largely alti- Asia that are south of the Himalaya, and a zone in tudinal. The foothills of the Himalaya with average China. North of this “line” is the Palearctic (consist- altitude between about 2000 – 2500 m a.s.l. form the ing og different subregions). This “line” (transitional boundary between the Palearctic and Indomalaya zone) is separating two kingdoms, therefore the dif- Ecoregions. -

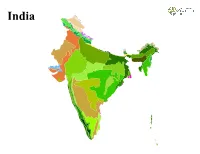

R Graphics Output

India India LEGEND Ecoregion Andaman Islands rain forests Mizoram−Manipur−Kachin rain forests Aravalli west thorn scrub forests Narmada Valley dry deciduous forests Baluchistan xeric woodlands Nicobar Islands rain forests Brahmaputra Valley semi−evergreen forests North Deccan dry deciduous forests Central Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Central Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe North Western Ghats montane rain forests Chhota−Nagpur dry deciduous forests Northeast Himalayan subalpine conifer forests Chin Hills−Arakan Yoma montane forests Northeast India−Myanmar pine forests Deccan thorn scrub forests Northern Triangle temperate forests East Deccan dry−evergreen forests Northwestern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows East Deccan moist deciduous forests Orissa semi−evergreen forests Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests Rock and Ice Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests Godavari−Krishna mangroves South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests South Western Ghats montane rain forests Himalayan subtropical pine forests Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests Indus River Delta−Arabian Sea mangroves Sundarbans mangroves Karakoram−West Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe Terai−Duar savanna and grasslands Khathiar−Gir dry deciduous forests Thar desert Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Malabar Coast moist forests Western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Maldives−Lakshadweep−Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests Western Himalayan broadleaf forests Meghalaya subtropical forests Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations From

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Human Biology Volume 85 Issue 1 Special Issue on Revisiting the "Negrito" Article 9 Hypothesis 2013 Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations from Luzon: Comparison of Male and Female Effective Population Sizes and Differential Integration of Immigrants into Aeta and Agta Communities E Heyer EcoAnthropologie et Ethnobiologie, MNHN, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France, [email protected] M Georges EcoAnthropologie et Ethnobiologie, MNHN, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France M Pachner Andaman and Nicobar Association, Liestal, Switzerland P Endicott EcoAnthropologie et Ethnobiologie, MNHN, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Recommended Citation Heyer, E; Georges, M; Pachner, M; and Endicott, P (2013) "Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations from Luzon: Comparison of Male and Female Effective Population Sizes and Differential Integration of Immigrants into Aeta and Agta Communities," Human Biology: Vol. 85: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/9 Genetic Diversity of Four Filipino Negrito Populations from Luzon: Comparison of Male and Female Effective Population Sizes and Differential Integration of Immigrants into Aeta and Agta Communities Abstract Genetic data corresponding to four negrito populations (two Aeta and two Agta; n = 120) from the Luzon region of the Philippines have been analyzed. These data comprise mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) hypervariable segment 1 haplotypes and haplogroups, Y-chromosome haplogroups and short tandem repeats (STRs), autosomal STRs, and X-chromosome STRs. -

Self Determination and Indigenous People: the Fight for 'Commons'

144 Medico-legal Update, January-March 2020, Vol.20, No. 1 DOI Number: 10.37506/v20/i1/2020/mlu/194313 Self Determination and Indigenous People: The Fight For ‘Commons’ Swati Mohapatra Assistant Professor, School of Law, K.I.I.T , Deemed to be University Abstract History has always seen the less-privileged as the one suffering the alienation of their rights, entitlements. It is equally true that these communities have fought back to claim what is rightfully theirs. The principle of Self determination or the right to decide how to be governed can be traced back to World War-1 and the principles laid down by Woodrow Wilson. This right to Self determination exists for each one of us. This becomes even more imminent when it belongs to a community which has its own preserved culture to protect, it has its own resources of which it is the foremost protector. Here the paper emphasizes how the tribals in India have now been reduced to a mere dependant and beggary.The paper traces the various changes of the Indian legal system governing the relationship between the ‘Commons’ and the Tribal Communities. But ‘the history of Forests is the history of conflicts’. The researcher has taken two case studies- the struggles of the Dongria-Kondhs of Odisha and the Sentinelese from Andaman , to show how these communities have in their own unparalleled ways protect their Commons from the never-ending appetite of the industrialization and human greed. Lastly, the researcher has analysed various provisions from the Corpus of Indian laws, to find out where is the State missing out. -

MEDLINE Definitions of Race and Ethnicity and Their Application to Genetic Research

CORRESPONDENCE 10. Royal College of Physicians. Retention of Medical 12. Medical Research Council. Human Tissue and 14. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Human Tissue: Ethical Records—with Particular Reference to Medical Biological Samples for Use in Research: Operational and Legal Issues. (Nuffield Council Publications, Genetics 2nd edn. (Royal College of Physicians and Ethical Guidelines. (Medical Research Council London, 1995). Publications, London, 1998). Publications, London, 2001). 15. Human Genome Organization (HUGO) Ethics 11. Medical Research Council. Personal Information in 13. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Genetic Screening: Committee. Statement on the Principled Conduct of Medical Research. (Medical Research Council Ethical Issues. (Nuffield Council Publications, Genetics Research. (HUGO International, London, Publications, London, 2000). London, 1993). 1996). MEDLINE definitions of race and ethnicity and their application to genetic research To the editor MeSH defines ethnic group as “a group of ‘Hamitic-Semitic’ subjects are referred to in Over the last five years, the use of MEDLINE people with a common cultural heritage that two articles8,9. From the Negroid racial stock has increased more than ten-fold, attesting to sets them apart from others in a variety of definition, ‘Hottentots’ returns a handful of the importance of the database in the social relationships.” MeSH lists 13 such articles, mostly historical. ‘Negrillos’ and scientific community (see http://www.nlm. groups, drawn primarily from United States ‘Half-Hamites’ -

The Last Island of the Savages

The Last Island of the Savages Journeying to the Andaman Islands to meet the most isolated tribe on Earth By Adam Goodheart | September 5, 2000 Ana Raquel S. Hernandes/Flickr The lumps of white coral shone round the dark mound like a chaplet of bleached skulls, and everything around was so quiet that when I stood still all sound and all movement in the world seemed to come to an end. It was a great peace, as if the earth had been one grave, and for a time I stood there thinking mostly of the living who, buried in remote places out of the knowledge of mankind, still are fated to share in its tragic or grotesque miseries. In its noble struggles too—who knows? The human heart is vast enough to contain all the world. It is valiant enough to bear the burden, but where is the courage that would cast it off? —Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim Shortly before midnight on August 2, 1981, a Panamanian-registered freighter called the Primrose, which was traveling in heavy seas between Bangladesh and Australia with a cargo of poultry feed, ran aground on a coral reef in the Bay of Bengal. As dawn broke the next morning, the captain was probably relieved to see dry land just a few hundred yards from the Primrose’s resting place: a low-lying island, several miles across, with a narrow beach of clean white sand giving way to dense jungle. If he consulted his charts, he realized that this was North Sentinel Island, a western outlier in the Andaman archipelago, which belongs to India and stretches in a ragged line between Burma and Sumatra. -

Chapter 2 Introduction to the Geography and Geomorphology Of

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on February 7, 2017 Chapter 2 Introduction to the geography and geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar Islands P. C. BANDOPADHYAY1* & A. CARTER2 1Department of Geology, University of Calcutta, 35 Ballygunge Circular Road, Kolkata-700019, India 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The geography and the geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar accretionary ridge (islands) is extremely varied, recording a complex interaction between tectonics, climate, eustacy and surface uplift and weathering processes. This chapter outlines the principal geographical features of this diverse group of islands. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license The Andaman–Nicobar archipelago is the emergent part of a administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Group. Other long ridge which extends from the Arakan–Yoma ranges of islands of importance are Katchal, Camorta, Nancowry, Till- western Myanmar (Burma) in the north to Sumatra in the angchong, Chowra, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. The lat- south. To the east the archipelago is flanked by the Andaman ter is the largest covering 1045 km2. Indira Point on the south Sea and to the west by the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1.1). A coast of Great Nicobar Island, named after the honorable Prime c. 160 km wide submarine channel running parallel to the Minister Smt Indira Gandhi of India, lies 147 km from the 108 N latitude between Car Nicobar and Little Andaman northern tip of Sumatra and is India’s southernmost point. -

Mongoloid-Caucasoid Differences in Brain Size from Military Samples

INTELLIGENCE 15, 351-359 (1991) Mongoloid-Caucasoid Differences in Brain Size From Military Samples J PHILIPPE RUSHTON Umverstty of Western Ontarto Cramal capactttes (cm3) were calculated from external head measurements of male mili- tary personnel For 24 mternaUonal samples totalhng 57,378 mthvtduals collated m 1978, after adjusting for the effects of height, wetght, and total body surface area, Mongoloids also averaged 1460 cm3 and Caucasoids averaged 1446 cm3 Another way of expressing the relaaonshtp ts m terms of an "encephaltzatlon quoaent" derived from the regression of cramal capacay on general body size, on which Mongolmds also averaged higher than Caucasotds The issue of whether human populations rehably differ m relatwe brain size, and whether brain size is correlated with mtelhgence, has a long and vexatious history Many 19th-century scientists including Broca, Darwin, Galton, Lombroso, and Morton, apphed a natural history perspectwe to human popula- Uons and concluded that there were racial differences in brain size With notable exceptions, for example, American anthropologists, Boas and Mead, this view was probably dominant until World War II Followmg the war, the hterature on bram size, mtelhgence, and race under- went vigorous cntlques Thus, with autopsy data, Tobms (1970) cited 14 poten- Ually confounding variables that he argued made the data on black-white dif- ferences m brain weight highly problematic With endocramal volume, Gould (1978) alleged that many data on racial &fferences were biased by "uncon- scious finaghng"