The Lost Land of Lemuria A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology . 2 Vols. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1977. Collected Writings . 11 Vols. Ed. by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. Campbell, B. 1980. Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement . Berkeley: University of California Press. -

Transcripts of Letters in Maine Voices from the Civil War

Transcripts of letters in Maine Voices from the Civil War The following documents have been transcribed as closely as possible to the way that they were written. Misspelled words, length of line, creative use of grammar follow the usage in the documents. Text in [brackets] are inserted or inferred by the transcriber. If they are accompanied by a question mark, it represents the transcribers best guess at the text. Most of the documents are from Maine State Museum (MSM) collections. The MSM number is our accession number. Items from other institutions are located at the end of the document. Those institutions include the Maine State Archives and the National Archives. More information about Maine State Archives documents can be found by searching their website using the writer’s name: http://www.maine.gov/sos/arc/sesquicent/civilwarwk.shtml Samuel Cony to Mrs. Elizabeth B. Leppien MSM 00.38.3 STATE OF MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT, Augusta, December 12, 1865. MRS. ELIZABETH B. LEPPIEN: Madam,—Your note of the 9th instant, announcing your pur- pose to present to the State of Maine the sword of your son, Lieut. Col. George F. Leppien, of the 1st Maine Light Artillery, is received. Be pleased to acdept my thanks in behalf of the Stte therefor. This sword, when received, shall be placed in the archives of the State, and preserved as a memento of that gallant young man who sacrificed his life upon the alter of his country. Col. Leppien, was neither a son or citizen of the State, except by adoption, but we nevertheless feel that he belongs to Maine, whose commission he bore with high honor to himself and to her. -

Th E O S O P H

JANUARY 1947 VOL. 68, No, 4 THE TH EOSOPH1ST Edited by C. JINARAJADASA CONTENTS PAGE The Presidential Address.C. JINARAJADASA . 213 Our Planetary Chain.A nnie B esant . 227 The Autobiography of A. P. Sinnett . 233 Ancient Ritual of the Magi in Iran.E rvad K. S. DABU . 240 The Teachings of Carpocrates. NG.evin D rinkwater . ,246 Day of Remembrance of Two World Wars . 249 Theosophy for the Artist.G eoffrey H odson . , 251 The Path of Holiness.M adeleine P ow ell . • 255 The Road to Utopia. U. KG.rishnamurti . • • 263 The Artist in us. Sidney A. Cook . 268 The Dance of Shiva.J ohn Moxford . 269' Reviews . 271 Supplement: Official Notice . 275 Theosophists at Work Around the World . 276 THE THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE ADYAR, MADRAS 20, INDIA ' THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY T he THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY was formed at New York, November 17, 1875, and incorpo rated at Madras, April 3, 1905, It is an absolutely unsectarian body of seekers after Truth, striving to serve humanity on spiritual lines, and therefore endeavouring to check materialism and revive the religious tendency. Its three declared Objects are : FIRST.— T o form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or colour. SECOND.—T o encourage the study of Comparative Religion, Philosophy and Science. T hird.— T o investigate the unexplained laws of Nature and the powers latent in man. THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the above objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. -

The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs

I The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs: Lost Races and Racism in American Popular Culture James R. Nesteby Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy August 1978 Approved: © 1978 JAMES RONALD NESTEBY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ¡ ¡ in Abstract The Tarzan series of Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), beginning with the All-Story serialization in 1912 of Tarzan of the Apes (1914 book), reveals deepseated racism in the popular imagination of early twentieth-century American culture. The fictional fantasies of lost races like that ruled by La of Opar (or Atlantis) are interwoven with the realities of racism, particularly toward Afro-Americans and black Africans. In analyzing popular culture, Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932) and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (1976) are utilized for their indexing and formula concepts. The groundwork for examining explanations of American culture which occur in Burroughs' science fantasies about Tarzan is provided by Ray R. Browne, publisher of The Journal of Popular Culture and The Journal of American Culture, and by Gene Wise, author of American Historical Explanations (1973). The lost race tradition and its relationship to racism in American popular fiction is explored through the inner earth motif popularized by John Cleves Symmes' Symzonla: A Voyage of Discovery (1820) and Edgar Allan Poe's The narrative of A. Gordon Pym (1838); Burroughs frequently uses the motif in his perennially popular romances of adventure which have made Tarzan of the Apes (Lord Greystoke) an ubiquitous feature of American culture. -

ABHANDLUNGEN DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Abh

ABHANDLUNGEN DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Abh. Geol. B.-A. ISSN 0378-0864 ISBN 978-3-85316-095-4 Band 72 S. 9–159 Wien, Jänner 2018 Zur Entwicklung der Paläontologie in Wien bis 1945 Zur Entwicklung der Paläontologie in Wien bis 1945 FRITZ F. STEININGER1, DANIELA ANGETTER2 & JOHANNES SEIDL3 gewidmet Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. ERICH THENIUS Ordinarius für Paläontologie und Paläobiologie an der Universität Wien 1965–1974 Vorstand des Instituts für Paläontologie der Universität Wien 40 Abbildungen Geschichte Paläontologie Sammlung Universität Wien Forschung Naturhistorisches Museum Studium Geologische Bundesanstalt Lehre Theresianum Inhalt Geleitworte ............................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ........................................................................................ 10 Abstract ................................................................................................ 10 Résumé................................................................................................. 10 Einleitung ............................................................................................... 10 1. Erste Ansätze der Paläontologie in Österreich................................................................. 11 2. Begriffsdefinitionen ..................................................................................... 13 3. Die Grundlagen der Paläontologie in Wien ................................................................... 15 3.1. Außeruniversitäre Sammlungen -

SEVEN YOUTHS DIE AS TRAIN Snmadto WASHINGTON EXCITED CAPITOUS FIRE

i i ■’'■ * ■ . ,' : '• ' ■ ■' ‘ ■ ■y--■■■■■-.* * ^ . * « « 'I'k o • • » » !*■•••• •.'•‘ ♦•kkn .7 ^ ^ •, L . ■ •• . V h. ... .1 V • • - • ' •- NET PRESS BUN . Forecast by f). S,. W egtte n v tfo rd . /AVERAGE DAILY CBRCULATION r ^ ',’ ' ■ for ttie* Month of Dooeinbcr, 1929. Fair and colder toidfht; Sunday 5 > 5 1 6 fto with rising temperatdfo. BlembeM of tlie Audit Bnreun of . i 1 ^ Clrcntatlona ^U T H MAN€HBSTBit,"C0NN.i SAtUBDAY, JANUARYji, 1930. ^OTEEIN PAG^ PRICE THREE CEN"r^ VOL. XLIV., NO. 81. (OlassMed Adverttslng on Page 18) ■« LAUGHTER AIDS CURBS SEVEN YOUTHS IN GERMAN HOSPITAL J. P. M O RG AN ’S GIFT TO U ; S.‘ Berlin, Jan. 4.— (A P )—Laugh FLEES ter has been added to the cura tive agents in the Charite Hospi HMSHINGOUT DIE AS TRAIN tal here. It happened rather accidental ly after a theatrical company had given a performance for I^GPROBLEMS Snm ADTO “chair cases” and patients able to navigate on crutches. “A Jump Into Matrimony” was the farce and it caused 5Yales of mer Foreii^ Minister of Ger- Roland Lalone Who KUkd Were Reluming from Bas- riment, many in the audience having their first laughs in To D riv e 80Q months. many Has Stormy Inter State Poficeman at Pom- ketbaU Game in Bus— AD In many of the csises, more over, the doctors found the ef view With Premier Tar- $1.50 fects of the laughter of distinct fret, One of Trio Who CnI High School Age— Eight therapeutic value. Consequently there are to be periodic repeti dien of France. (AP) —Afand reach New York next Monday Bars in Skylight and Es Others Are Injured. -

Proceedings Geological Society of London

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of California-San Diego on February 18, 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON. SESSION 1884-851 November 5, 1884. Prof. T. G. Bo~sEY, D.Sc., LL.D., F.R.S., President, in the Chair. William Lower Carter, Esq., B.A., Emmanuel College, Cambridge, was elected a Fellow of the Society. The SECRETARYaunouneed.bhat a water-colour picture of the Hot Springs of Gardiner's River, Yellowstone Park, Wyoming Territory, U.S.A., which was painted on the spot by Thomas Moran, Esq., had been presented to the Society by the artist and A. G. Re"::~aw, Esq., F.G.S. The List of Donations to the Library was read. The following communications were read :-- 1. "On a new Deposit of Pliocene Age at St. Erth, 15 miles east of the Land's End, Cornwall." By S. V. Wood, Esq., F.G.S. 2. "The Cretaceous Beds at Black Ven, near Lyme Regis, with some supplementary remarks on the Blackdown Beds." By the Rev. W. Downes, B.A., F.G.S. 3. "On some Recent Discoveries in the Submerged Forest of Torbay." By D. Pidgeon, Esq., F.G.S. The following specimens were exhibited :- Specimens exhibited by Searles V. Wood, Esq., the Rev. W. Downes, B.A., and D. Pidgeon, Esq., in illustration of their papers. a Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of California-San Diego on February 18, 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. A worked Flint from the Gravel-beds (? Pleistocene) in the Valley of the Tomb of the Kings, near Luxor (Thebes), Egypt, ex- hibited by John E. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Western Indologists: a Study in Motives

Agniveer http://agniveer.com DISTORTION OF BHARTIYA HISTORY: SOME CAUSES WESTERN INDOLOGISTS: A STUDY IN MOTIVES BY PT. BHAGVAD DATT RESEARCH SCHOLAR (EDITED BY DR. VIVEK ARYA) Agniveer http://agniveer.com Preface by Pt.Bhagavad Data research scholar The present monograph is an amplified English version of the first argument of chapter III of my Bharatavarsha ka Brihad Itihasa Vol I (published in 1951). I have under taken this task in response to persistent requests from friends and scholars who read that volume in advance proofs and also in its published form. Being hard pressed for time, I requested my friend Prof. Sadhu Ram, M.A., to prepare the English version for me. He was kind enough to comply with my request, and placed the manuscript at my disposal by the end of 1950. Further material was added to it, and the monograph assumed the present shape. There is a widespread belief among Indian scholars and the educated public that western Orientalists and indologists have been invariably actuated by purely academic interests, pursued in an objective, scientific and critical spirit. While some of them have undoubtedly approached their task in an unimpeachable manner, it is not so well-known that a vast majority of them, who have exercised tremendous influence in the world of scholarship, have been motivated by extraneous considerations, both religious and political. It is the object of this study to throw some light on this important aspect of western scholarship. I have been reluctantly driven to the painful conclusion that the bulk of what today passes as ‘scientific’, ‘objective’ and ‘critical’ research, is, in fact, vitiated by the underlying and subtle influence exercised by none too academic motives. -

College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper Number 137

The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System Harriet Orcutt Duleep (Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy, College of William and Mary and IZA- Institute for the Study of Labor) College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper Number 137 March 2013 COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER # 137 March 2013 The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System Abstract This paper proposes that India’s caste system and involuntary labor were joint responses by a nonworking landowning class to a low labor/land ratio in which the rules of the caste system supported the institution of involuntary labor. The hypothesis is tested in two ways: longitudinally, with data from ancient religious texts, and cross-sectionally, with twentieth-century statistics on regional population/land ratios linked to anthropological measures of caste-system rigidity. Both the longitudinal and cross-sectional evidence suggest that the labor/land ratio affected the caste system’s development, persistence, and rigidity over time and across regions of India. JEL Codes: J47, J1, J30, N3, Z13 Keywords: labor-to-land ratio, population, involuntary labor, immobility, value of life, marginal product of labor, market wage Harriet Duleep Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy College of William and Mary Williamsburg VA 23187-8795 [email protected] The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System I. Background Several scholars have observed that, historically, the caste system was more rigid in south India than in other parts of India. In the 1930’s, Gunther (1939, p. 378) described south India as the “...home of Hinduism in its most intensive form...virtually a disease... -

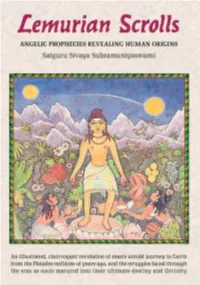

Lemurian-Scrolls.Pdf

W REVIEWS & COMMENTS W Sri Sri Swami Satchidananda, people on the planet. The time is now! Thank you Founder of Satchidananda so much for the wonderful information in your Ashram and Light of Truth book! It has also opened up many new doorways Universal Shrine (LOTUS); for me. renowned yoga master and visionary; Yogaville, Virginia K.L. Seshagiri Rao, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus, Lemurian Scrolls is a fascinating work. I am sure University of Virginia; Editor of the quarterly the readers will find many new ideas concern- journal World Faiths ing ancient mysteries revealed in this text, along Encounter; Chief Editor with a deeper understanding of their impor- of the forthcoming tance for the coming millenium. Encyclopedia of Hinduism Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, a widely recog- Patricia-Rochelle Diegel, nized spiritual preceptor of our times, un- Ph.D, well known teacher, veils in his Lemurian Scrolls esoteric wisdom intuitive healer and concerning the divine origin and goal of life consultant on past lives, for the benefit of spiritual aspirants around the human aura and numerology; Las Vegas, the globe. Having transformed the lives of Nevada many of his disciples, it can now serve as a source of moral and spiritual guidance for I have just read the Lemurian Scrolls and I am the improvement and fulfillment of the indi- amazed and pleased and totally in tune with vidual and community life on a wider scale. the material. I’ve spent thirty plus years doing past life consultation (approximately 50,000 to Ram Swarup, intellectual date). Plus I’ve taught classes, seminars and re- architect of Hindu treats. -

The Labor/Land Ratio and India's Caste System

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Duleep, Harriet Working Paper The labor/land ratio and India's caste system IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6612 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Duleep, Harriet (2012) : The labor/land ratio and India's caste system, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6612, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/62558 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IZA DP No. 6612 The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System Harriet Orcutt Duleep May 2012 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System Harriet Orcutt Duleep College of William and Mary and IZA Discussion Paper No.