Is Ur and Assur the Same

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

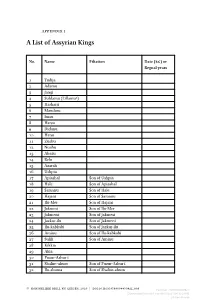

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Lots of Eponyms

167 LOTS OF EPONYMS By i. L. finkel and j. e. reade O Ashur, great lord! O Adad, great lord! The lot of Yahalu, the great masennu of Shalmaneser, King of Ashur; Governor of Kipshuni, Qumeni, Mehrani, Uqi, the cedar mountain; Minister of Trade. In his eponymate, his lot, may the crops of Assyria prosper and flourish! In front of Ashur and Adad may his lot fall! Millard (1994: frontispiece, pp. 8-9) has recently published new photographs and an annotated edition of YBC 7058, a terracotta cube with an inscription relating to the eponymate of Yahalu under Shalmaneser III. Much ink has already been spilled on account of this cube, most usefully by Hallo (1983), but certain points require emphasis or clarification. The object, p?ru, is a "lot", not a "die". Nonetheless the shape of the object inevitably suggests the idea of a true six-sided die, and perhaps implies that selections of this kind were originally made using numbered dice, with one number for each of six candidates. If so, it is possible that individual lots were introduced when more than six candidates began to be eligible for the post of limmu. The use of the word p?ru as a synonym for limmu in some texts, including this one, must indicate that eponyms were in some way regarded as having been chosen by lot. Lots can of course be drawn in a multitude of ways. Published suggestions favour the proposal that lots were placed in a narrow-necked bottle and shaken out one by one, an idea that seems to have originated with W. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 06:11:41PM Via Free Access 208 Appendix III

Appendix III The Selected Synchronistic Kings of Assyria and Babylonia in the Lacunae of A.117 1 Shamshi-Adad I / Ishme-Dagan I vs. Hammurabi The synchronization of Hammurabi and the ruling family of Shamshi-Adad I’s kingdom can be proven by the correspondence between them, including the letters of Yasmah-Addu, the ruler of Mari and younger son of Shamshi-Adad I, to Hammurabi as well as an official named Hulalum in Babylon1 and those of Ishme-Dagan I to Hammurabi.2 Landsberger proposed that Shamshi-Adad I might still have been alive during the first ten years of Hammurabi’s reign and that the first year of Ishme- Dagan I would have been the 11th year of Hammurabi’s reign.3 However, it was also suggested that Shamshi-Adad I would have died in the 12th / 13th4 or 17th / 18th5 year of Hammurabi’s reign and Ishme-Dagan I in the 28th or 31st year.6 If so, the reign length of Ishme-Dagan I recorded in the AKL might be unreliable and he would have ruled as the successor of Shamshi-Adad I only for about 11 years.7 1 van Koppen, MARI 8 (1997), 418–421; Durand, DÉPM, No. 916. 2 Charpin, ARM 26/2 (1988), No. 384. 3 Landsberger, JCS 8/1 (1954), 39, n. 44. 4 Whiting, OBOSA 6, 210, n. 205. 5 Veenhof, AP, 35; van de Mieroop, KHB, 9; Eder, AoF 31 (2004), 213; Gasche et al., MHEM 4, 52; Gasche et al., Akkadica 108 (1998), 1–2; Charpin and Durand, MARI 4 (1985), 293–343. -

Modeling Strategic Decisions in the Formation of the Early Neo

Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution Modeling Strategic Decisions in the Formation of the Early Neo-Assyrian Empire Peter Baudains, Silvie Zamazalová, Mark Altaweel, Alan Wilson University College London Understanding patterns of conflict and pathways in which political history became established is critical to understanding how large states and empires ultimately develop and come to rule given regions and influence subsequent events. We employ a spatiotemporal Cox regression model to investigate possible causes as to why regions were attacked by the Neo-Assyrian (912-608 BCE) state. The model helps to explain how strategic benefits and costs lead to likely pathways of conflict and imperialism based on elite strategic decision-making. We apply this model to the early 9th century BCE, a time when historical texts allow us to trace yearly campaigns in specific regions, to understand how the Neo-Assyrian state began to re-emerge as a major political player, eventually going on to dominate much of the Near East and starting a process of imperialism that shaped the wider region for many centuries even after the fall of this state. The model demonstrates why specific locations become regions of conflict in given campaigns, emphasizing a degree of consistency with which choices were made by invading forces with respect to a number of factors. We find that elevation and population density deter Assyrian invasions. Moreover, costs were found to be more of a clear motivator for Assyrian invasions, with distance constraints being a significant driver in determining where to campaign. These outputs suggest that Assyria was mainly interested in attacking its weakest, based on population and/or organization, and nearest rivals as it began to expand. -

Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat)

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1130.pdf UNESCO Region: ASIA AND THE PACIFIC __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat) DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 5th July 2003 STATE PARTY: IRAK CRITERIA: C (iii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 27th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion iii: Founded in the 3rd millennium BCE, the most important role of Ashur was from the 14th to 9th century BCE when it was the first capital of the Assyrian empire. Ashur was also the religious capital of Assyrians, and the place for crowning and burial of its kings. Criterion iv: The excavated remains of the public and residential buildings of Ashur provide an outstanding record of the evolution of building practice from the Sumerian and Akkadian period through the Assyrian empire, as well as including the short revival during the Parthian period. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS The ancient city of Ashur is located on the Tigris River in northern Mesopotamia in a specific geo-ecological zone, at the borderline between rain-fed and irrigation agriculture. The city dates back to the 3rd millennium BC. From the 14th to the 9th centuries BC it was the first capital of the Assyrian Empire, a city-state and trading platform of international importance. It also served as the religious capital of the Assyrians, associated with the god Ashur. The city was destroyed by the Babylonians, but revived during the Parthian period in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger: 2003 Threats to the Site: Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat) was inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger at the 27th session of the World Heritage Committee simultaneously with its inscription on the World Heritage List. -

Babylon and Assyria Second Millennium

Babylon and Assyria Second Millennium • Competing city states • Old Elamite Period – ca. 2700 - 1900 • Amorites • ca. 2000 - 1600 – Semitic language – Precursor to Hebrew (?) Amorite & Elamite Amorite Elamite Assyria • Ashur – Name of the city and the god – Controlled the tin and copper trade routes • Shamshi-Adad – King of Ashur 1813 – 1781 – An Amorite who conquered the city Ashurr Amorites Elam Babylon Ashurr Amorites Elam Babylon The Rise of Babylon • Ca. 2000 – 1800 BC – Collapse of the Amorites and Elamites. – Intercity warfare • Hammurabi (1792 – 1750) Hammurabi • Year 7 – 11 – Allied with Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria and Rim-Sin of Larsa. • 1763 – 1760: – Conqured Larsa, all of the south and then Assyria. Ashurr Amorites Elam Babylon The Horse • Equus (wild horse): – Hunted to extinction in Europe. – Equus Cabalus evolved on the Russian Steppe. – domesticated ca. 3000 BC. • Early Horses: – Front legs and chest too weak to support a rider. – Neck too weak to pull using the collar. – Difficult to control until the bit was invented. • Equus Onager (wild ass): – Easier to control – Stronger Transportation • Carts: • Drawn by onagers (equus onager) • Four solid wheels appear c.3000 BC. In Sumer • The two-part wheel appears at Ur. • Chariots: • Developed on the Armenian and Cappadocian plateau ca.2000 Theory now disputed by Khurt Early Chariots Early Chariots Charioteers Charioteers • c.2000 BC. (traditional view) • c.1600 BC. (radical view - Drews) • Volkerwanderung Theory – Entire ethnic group on the move. – A peaceful transition and assimilation. • Mass Invasion Theory – Conquering army brings its entire culture with it. – Indigenous population ejected or eliminated. • Warrior Elite Theory (Drews) – Small band of warriors invades – Indigenous population become serfs Asshurubalit 1365 BC Tut Chariot Hittites • 1650 – ca. -

Sennacherib's Campaign Against Judah

MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY ANCIENT ISRAEL SCHOOL RESOURCES Stage 6 Ancient History: Historical Period Option C: The Ancient Levant – First Temple Period c. 970–586 BC Foreign relations with Assyria and Babylon, including: The contributing factors and outcomes of the campaign of Assyrian King Sennacherib against Judah in 701 BC Sennacherib’s campaign against Judah In the year 701 BCE, the Assyrian King Sennacherib led a campaign against Judah and its king Hezekiah. What are the sources for this campaign and how can they help us to construct an accurate account of this event? Sourcebook for HSC Ancient History Dr Eve Guerry and Mr John McVittie MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY ANCIENT ISRAEL SCHOOL RESOURCES Map of Israel and Judah during the 8th century BCE https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kingdoms_of_Israel_and_Judah_map_830.svg Sourcebook for HSC Ancient History MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY ANCIENT ISRAEL SCHOOL RESOURCES The Hebrew Bible accounts of Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah Source A. “In the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah, Sennacherib, king of Assyria, went on an expedition against all the fortified cities of Judah and captured them. Hezekiah, king of Judah, sent this message to the king of Assyria at Lachish: ‘I have done wrong. Leave me, and I will pay whatever tribute you impose on me.’ The king of Assyria exacted 300 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold from Hezekiah, king of Judah. Hezekiah paid him all the funds there were in the temple of the Lord and in the palace treasuries...” 2 Kings 18:13 Source B. “Then King Sennacherib of Assyria invaded Judah and besieged its fortified cities and gave orders for his army to break their way through the walls.…” 2 Chronicles 32:1 Sourcebook for HSC Ancient History MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY ANCIENT ISRAEL SCHOOL RESOURCES The Annals of Sennacherib Three copies of the annals are known. -

Assyria - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 11/5/09 12:28 PM

Assyria - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 11/5/09 12:28 PM Assyria From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ancient Assyria was a civilization centered on the Upper Tigris river, in Mesopotamia Mesopotamia (Iraq), that came to rule regional empires a number of times in history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur (Akkadian: Aššur; Arabic: .(Atur ݏݏݏݏ ,Ašur ݏݏݏݏ :Aššûr, Aramaic אַשור :Aššûr; Hebrew ﺃﺷﻮﺭ The term Assyria can also refer to the geographic region or heartland where these empires were centered. During the Old Assyrian period (20th to 15th c. BCE, Assur controlled much of Euphrates · Tigris Upper Mesopotamia. In the Middle Assyrian period (15th to 10th c. BCE), its Sumer influence waned and was subsequently regained in a series of conquests. The Neo- Eridu · Kish · Uruk · Ur Lagash · Nippur · Ngirsu Assyrian Empire of the Early Iron Age (911 – 612 BCE) expanded further, and Elam under Ashurbanipal (r. 668 – 627 BCE) for a few decades controlled all of the Susa Fertile Crescent, as well as Egypt, before succumbing to Neo-Babylonian and Akkadian Empire Median expansion, which were in turn conquered by the Persian Empire. Akkad · Mari Amorites Isin · Larsa Contents Babylonia Babylon · Chaldea 1 Early history Assyria Assur · Nimrud 2 Old Assyrian city-states and kingdoms Dur-Sharrukin · Nineveh 2.1 City state of Ashur Hittites · Kassites 2.2 Kingdom of Shamshi-Adad I Ararat / Mitanni 2.3 Assyria reduced to vassal states Chronology 3 Middle Assyrian period Mesopotamia 3.1 Ashur-uballit I Sumer (king list) -

Ancient Mesopotamian Religion and Gods the Ancient Mesopotamians Worshipped Hundreds of Gods Which They Worshipped Every Day

Ancient Mesopotamian Religion and Gods The ancient Mesopotamians worshipped hundreds of gods which they worshipped every day. Each god had a job to do. Each city had its own special god to watch over the city. Each profession had a god to watch over the people who worked in that profession like builders and fishermen. At the center of the city was a large ziggurat built to that god. This was where the priests would live and make sacrifices. Some of the ziggurats were huge and reached great heights. They looked like step pyramids with a flat top. Ancient Sumer: The ancient Sumerians were very religious people where they worshipped many different gods and goddesses. To the Sumerians, each person had a god of their own, who looked after them. They believed that they had their own special god talked to other gods on their behalf. Their personal god received a great deal of their worship time and attention. But no one god was more important than another. They believed that everything that happened good or bad was a result of their gods. They worked hard to make their gods happy. This was quite difficult since they had hundreds of gods, and they were not a happy bunch. In fact they were downright grumpy. So the Sumerians spent a lot of their time and effort seeking new ways to please their gods. The Babylonians and Assyrians believed in nearly all the Sumerian gods, plus more gods that each added. Unlike the ancient Sumerians, they believed some gods were more powerful than others, gods like the god of the sky, the sun, the air, and the crops. -

Situation and Organisation: the Empire Building of Tiglath-Pileser Iii (745-728 Bc)

SITUATION AND ORGANISATION: THE EMPIRE BUILDING OF TIGLATH-PILESER III (745-728 BC) T.L. Davenport, PhD (Ancient History), The University of Sydney, 2016 1 CONTENTS Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………............... 5 Tables and Figures ………………………………………………………………………............... 6 Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………….................... 7 CHAPTER 1 Introduction 1.1 The Historical Background to Tiglath-pileser III‘s Reign …………………………………….. 8 1.2 What was the Achievement of Tiglath-pileser III? ……………………………………………. 10 CHAPTER 2 The Written Evidence 2.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 20 2.2 The Assyrian Royal Inscriptions …………………………………………………………….... 20 2.2.1 The Creation and Maintenance of Empire according to the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions ….. 22 2.3 The Eponym Chronicle ……………………………………………………………………….. 24 2.4 The Babylonian Chronicle ……………………………………………………………………. 32 2.5 Assyrian Letters ………………………………………………………………………………. 33 CHAPTER 3 The Accession of Tiglath-pileser III: Usurpation or Legitimate Succession? 3.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 36 3.2 The Eponym Chronicle………………………………………………………………………… 37 3.3 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………... 40 CHAPTER 4 The Conquest of Babylonia and the Origins and Evolution of Tiglath-pileser’s ‘Babylonian Policy’ 4.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 4.2 Terminology ……………………………………………………………………………………45 4.3 Babylonian Population Groups ……………………………………………………………….. 47 4.4 The Written Evidence …………………………………………………………………………. 53 4.4.1 The ARI …………………………………………………………………………………….. -

In Assyrian Royal Inscriptions by Mattias Karlsson

The Expression “Son of a Nobody” in Assyrian Royal Inscriptions by Mattias Karlsson 1. Introductory remarks The creating of enemy images is a universal and timeless phenomenon.1 In this process, an abnormal “Other” is negatively stereotyped in relation to a normal “Self”, not the least in political discourse. In various contexts - notably ones that involve the topic of colonialism - a “subaltern” is constructed, that is an agent who is both inferior (thus “sub”) and different in a fundamentally bad way (thus “altern”). Through the developing of images of “alterity”, various oppressive systems can be justified. In this way, a colonial power can legitimate its possession of foreign lands and resources.2 Enemy images are conveyed not the least in Assyrian royal inscriptions in which Assyrian kings seek to legitimate their coercion and imperialist wars and ambitions. As a doctoral student, focusing on this text corpus, I became very aware of this. One enemy image that I encountered, and which I decided to return to when I had the time, was the suggestive term or epithet “son of a nobody” (mār lā mamman)3, applied to some foreign rulers in Early Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions. Most often derogatory in meaning, I noticed that this term could also have positive connotations in certain contexts.4 In this article, I present the results of my investigations on all this. To my knowledge, the term in question has not been the topic of a separate study before,5 although it of course has been frequently noted in scholarly works.6 Anyway, the contexts of the relevant expression, more precisely the textual passages in which the expression occurs, was highlighted in my analysis and search for meanings.7 In my investigation process, I searched for further attestations by surveying the preserved Assyrian royal inscriptions (as defined in Grayson 1987: 4), as these are conveyed in up-to-date publications. -

The Historical Development Of

CERTAIN ASPECTS OF THE GODDESS IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST (10,000 - 330 BCE) by JENNETTE ADAIR submitted in part fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH SPECIALISATION IN ANCIENT LANGUAGES AND CULTURES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR P.S. VERMAAK CO-SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR W. S. BOSHOFF FEBRUARY 2008 CERTAIN ASPECTS OF THE GODDESS WITHIN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST (10,000 – 330 BCE). SUMMARY In the historical tapestry of the development of the Goddess, from 10,000 – 330 BCE one golden thread shines through. Despite the vicissitudes of differing status, she remained essentially the same, namely divine. She was continuously sought in the many mysteries, mystic ideologies and through the manifestations that she inspired. In all the countries of the Ancient Near East, the mother goddess was the life giving creatrix and regenerator of the world and the essence of the generating force that seeds new life. While her name may have altered in the various areas, along with that of her consort/lover/child, the myths and rituals which formed a major force in forming the ancient cultures would become manifest in a consciousness and a spiritual awareness. Key Terms. Goddess; Ancient Near East; Pre-history; Neolithic Age; Figures: Çatalhüyök (Anatolia; modern Turkey); Bronze Age: writings: Goddess, in Mesopotamia, Inanna/Ishtar; in Canaan, Asherah/Athirat/Ashratu; Iron Age goddess; Asherah in Canaan and Israel. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i - x CHAPTER I ANATOLIAN GODDESS 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Çatalhöyük 3 1.3 Symbolism At Çatalhöyük 6 1.4 Çatalhöyük: Closed and Reopened 18 1.5 Conclusion 22 CHAPTER II THE SUMERIAN AND AKKADIAN GODDESS 24 2.1 Introduction 24 2.2.