NATIONAL LIFE STORIES CITY LIVES Sir Roger Gibbs Interviewed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

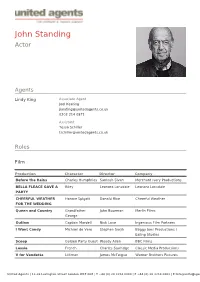

John Standing Actor

John Standing Actor Agents Lindy King Associate Agent Joel Keating [email protected] 0203 214 0871 Assistant Tessa Schiller [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company Before the Rains Charles Humphries Santosh Sivan Merchant Ivory Productions BELLA FLEACE GAVE A Riley Leonora Lonsdale Leonora Lonsdale PARTY CHEERFUL WEATHER Horace Spigott Donald Rice Cheerful Weather FOR THE WEDDING Queen and Country Grandfather John Boorman Merlin Films George Outlaw Captain Mardell Nick Love Ingenious Film Partners I Want Candy Michael de Vere Stephen Surjik Baggy Joes Productions / Ealing Studios Scoop Golden Party Guest Woody Allen BBC Films Lassie French Charles Sturridge Classic Media Productions V for Vendetta Lilliman James McTeigue Warner Brothers Pictures United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company The Best Man Stefan Schwartz Endgame Entertainment Brothers of the Head Keith Fulton & Luis Potboiler Productions / Film4 Pepe Rabbit Fever Ally's Dad Ian Denyer Rabbit Reproductions Ltd Animal Dean Frydman Rose Bosch Studio Legende A Good Woman Dumby Mike Barker Meltemi Entertainment Shoreditch Jenson Thackery Malcolm Needs Bauer Martinez Studios Jack Brown and the Sheldon Gotti Andrew Gilman Curse of the Crown Queen's Messenger Foreign Secretary Mark Roper Boyana Film The Calling Jack Plummer Richard Ceasar Summit Entertainement Mad Cows Politician Sara Sugarman Newmarket Capital -

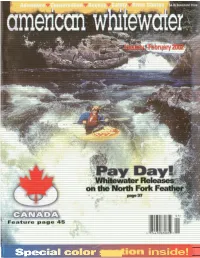

Y E I O N Inside!

yeion inside! FALL IN. LOVE 2.7 SECONDS. I IF YOU DON'T BELIEVE IN LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT IT'S BECAUSE YOU'VE NEVER LAID EYES ON THE JAVATM BEFORE. THIS HIGHLY RESPONSIVE CREEK BOAT MEASURES IN AT 7'9:' WEIGHS ONLY 36 LBS AND ANSWERS YOUR EVERY DESIRE WHEN PADDLING AGGRESSIVE LINES. AND WHEN IT COMES TO DROPPING OVER FALLS. ITS STABILITY AND VOLUME PROVIDE EFFORTLESS BOOFS AND PILLOW- SOFT LANDINGS.WHETHER YOU'RE 7 A BEGINNING CREEKER OR AN OLD HAND, ONCE YOU CLIMB INTO A JAVA YOU'LL KNOW WHY THEY CALL IT FALLING IN LOVE. Forum ......................................4 Features Corner Charc .................................... 8 Letters .................................... 10 When Rashfloods Hit Conservation .................................. 16 IFERC Takes Balanced Approach on Housatonic Access .................................. 18 IAccess Flash Reports Whitewater Releases on the North IFlow Study on the Cascades of the Nantahala Fork Feather IGiving the Adirondacks Back to Kayaks IUpper Ocoee Update Events .................................. 24 Canada Sechon IIf You Compete, You need to Know This IMagic is Alive and Music is Afoot Dams Kill Rivers in Canada Too! INew Method for Paddlers JimiCup 2001 IRace Results ISteep Creeks of New England, A Review Saving the Gatineau! River Voices ................................... 64 IGauley Secrets Revealed IBlazing Speedfulness s Dave's Big Adventure IWest Virginia Designed by Walt Disney INotes on a Foerfather ILivin' the Dream in South America Whitewater Love Trouble .................... 76 Cover: Jeff Prycl running a good one in Canada. Issue Date: JanuaryIFebrua~2002 Statement oi Frequencv: Published bimonthly Authorized Organization's Name and Address: American Whitewater P.O. Box 636 Prmted OII Fit3 ,pled Paper Margreb~lle,NY 12455 American Whitewater Januaty February 2002 ing enough for most normal purposes, but he does have a girlfriend and she has a gun and knows how to use it. -

Alpine Adventures 2019 68

RYDER WALKER THE GLOBAL TREKKING SPECIALISTS ALPINE ADVENTURES 2019 68 50 RYDER WALKER ALPINE ADVENTURES CONTENTS 70 Be the first to know. Scan this code, or text HIKING to 22828 and receive our e-newsletter. We’ll send you special offers, new trip info, RW happenings and more. 2 RYDERWALKER.COM | 888.586.8365 CONTENTS 4 Celebrating 35 years of Outdoor Adventure 5 Meet Our Team 6 Change and the Elephant in the Room 8 Why Hiking is Important – Watching Nature 10 Choosing the Right Trip for You 11 RW Guide to Selecting Your Next Adventure 12 Inspired Cuisine 13 First Class Accommodations 14 Taking a Closer Look at Huts 15 Five Reasons Why You Should Book a Guided Trek 16 Self-Guided Travel 17 Guided Travel & Private Guided Travel EASY TO MODERATE HIKING 18 Highlights of Switzerland: Engadine, Lago Maggiore, Zermatt 20 England: The Cotswolds 22 Isola di Capri: The Jewel of Southern Italy NEW 24 French Alps, Tarentaise Mountains: Bourg Saint Maurice, Sainte Foy, Val d’Isère 26 Sedona, Arches & Canyonlands 28 Croatia: The Dalmatian Coast 28 30 Engadine Trek 32 Scotland: Rob Roy Way 34 Montenegro: From the Durmitor Mountain Range to the Bay of Kotor 36 New Mexico: Land of Enchantment, Santa Fe to Taos NEW 38 Slovakia: Discover the Remote High Tatras Mountains NEW MODERATE TO CHALLENGING HIKING 40 Heart of Austria 42 Italian Dolomites Trek 44 High Peaks of the Bavarian Tyrol NEW 46 Sicily: The Aeolian Islands 48 Rocky Mountain High Life: Aspen to Telluride 50 New Brunswick, Canada: Bay of Fundy 52 Via Ladinia: Italian Dolomites 54 Dolomiti di -

HUMAN GENE MAPPING WORKSHOPS C.1973–C.1991

HUMAN GENE MAPPING WORKSHOPS c.1973–c.1991 The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group, Queen Mary University of London, on 25 March 2014 Edited by E M Jones and E M Tansey Volume 54 2015 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2015 First published by Queen Mary University of London, 2015 The History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 1 91019 5031 All volumes are freely available online at www.histmodbiomed.org Please cite as: Jones E M, Tansey E M. (eds) (2015) Human Gene Mapping Workshops c.1973–c.1991. Wellcome Witnesses to Contemporary Medicine, vol. 54. London: Queen Mary University of London. CONTENTS What is a Witness Seminar? v Acknowledgements E M Tansey and E M Jones vii Illustrations and credits ix Abbreviations and ancillary guides xi Introduction Professor Peter Goodfellow xiii Transcript Edited by E M Jones and E M Tansey 1 Appendix 1 Photographs of participants at HGM1, Yale; ‘New Haven Conference 1973: First International Workshop on Human Gene Mapping’ 90 Appendix 2 Photograph of (EMBO) workshop on ‘Cell Hybridization and Somatic Cell Genetics’, 1973 96 Biographical notes 99 References 109 Index 129 Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications 141 WHAT IS A WITNESS SEMINAR? The Witness Seminar is a specialized form of oral history, where several individuals associated with a particular set of circumstances or events are invited to meet together to discuss, debate, and agree or disagree about their memories. The meeting is recorded, transcribed, and edited for publication. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI' The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties By Nancy McGuire Roche A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University May 2011 UMI Number: 3464539 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3464539 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: Dr. William Brantley, Committees Chair IVZUs^ Dr. Angela Hague, Read Dr. Linda Badley, Reader C>0 pM„«i ffS ^ <!LHaAyy Dr. David Lavery, Reader <*"*%HH*. a*v. Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department ;jtorihQfcy Dr. Michael D1. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: vW ^, &v\ DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the women of my family: my mother Mary and my aunt Mae Belle, twins who were not only "Rosie the Riveters," but also school teachers for four decades. These strong-willed Kentucky women have nurtured me through all my educational endeavors, and especially for this degree they offered love, money, and fierce support. -

Bruce Brothers Win Start up of the Year Road Trip of A

Old Stoic Society Committee President: Sir Richard Branson (Cobham/Lyttelton 68) Vice President: THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Dr Anthony Wallersteiner (Headmaster) Chairman: Jonathon Hall (Bruce 79) Issue 6 Vice Chair: Hannah Durden (Nugent 01) Director: Anna Semler (Nugent 05) Treasurer: Peter Comber (Grenville 70) Members: Paul Burgess (Cobham 89) Tim Hart (Chandos 92) Jonathan Keating (Conham 73) Katie Lamb (Lyttelton 06) Ben Mercer (Development Director) Phoebe English (Nugent 04) is causing Nigel Milne (Chandos 68) waves with her de-constructed fashion. Simon Shneerson (Temple 72) Jules Walker (Lyttelton 82) ROAD TRIP OF A LIFETIME Mike Andrews (Chatham 57) relives an epic 43,500 mile journey. BRUCE BROTHERS WIN START UP OF THE YEAR Charlie (Bruce 07) and Harry Thuillier (Bruce 04) win the Guardian’s start up of the Year for their healthy Ice Cream, Oppo. Old Stoic Society Stowe School Stowe Buckingham MK18 5EH United Kingdom Telephone: +44 (0) 1280 818349 Email: [email protected] www.oldstoic.co.uk www.facebook.com/OldStoicSociety ISSN 2052-5494 Design and production: MCC Design, mccdesign.com Photographer, Chloe Newman. OLD STOIC DAY 2016 EVENTS CALENDAR We have endeavoured to organise a wide range of events in 2016 that will appeal Saturday 17 September 2016 to Old Stoics of all ages. To make enquiries or to book any of the events below please call the Old Stoic Office on01280 818349 or email [email protected] Full details of each event can be found at www.oldstoic.co.uk To see more photos visit the OS Event Gallery at www.oldstoic.co.uk -

John Standing Belgravia Magazine April 2019

BelgraviaAPRIL 2019 #154 HATS OFF Millinery masterpieces and gorgeous gifts for Mother's Day in our new look magazine ALSO INSIDE: Meet Instagram sensation Luna De Casanova Wine and dine at the Jones Family Kitchen Showstopping spaces by Ana Engelhorn Culture ir John Standing is holding court in the only way he knows how. Within minutes of entering his treasure trove of a home – a former 19th century stables, top-to- toe with theatre and film memorabilia in homage to his fabulously colourful life – the Sdistinguished actor is staging a tour-de-force performance. He’s 84, but you would never know it. He has the raw energy of a boisterous border collie and flits from one topic to the next – rat-a-tat – with the occasional segue into an outrageous anecdote. We cover Brexit while he makes builder’s tea (he voted remain and booms that “it’s just b****y rude!”), the new TV in his studio (“my wife gave it to me for Christmas, look at this f****** thing, boom!”) and there is even time for a brief, impromptu tap dance (he is soon to star in cabaret at The Pheasantry in Chelsea). This is glorious, old-school charm at its finest. There is no self-censoring whatsoever; he peppers sentences with expletives, discloses starry tales at the drop of a bowler hat and is candid about the good, the bad and the occasionally ugly. We meet to chew the cud about his upcoming exhibition at Belgravia’s Osborne Studio Gallery – an art student in the 1950s, John’s paintings have been showcased in London and America, with a selection of landscapes from India to LA heading to Motcomb Street next month – but soon venture deliciously off-piste. -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no. -

Postmaster and the Merton Record 2019

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2019 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Edited by Timothy Foot (2011), Claire Spence-Parsons, Dr Duncan From the Acting Warden......................................................................4 Barker and Philippa Logan. JCR News .................................................................................................6 Front cover image MCR News ...............................................................................................8 St Alban’s Quad from the JCR, during the Merton Merton Sport ........................................................................................10 Society Garden Party 2019. Photograph by John Cairns. Hockey, Rugby, Tennis, Men’s Rowing, Women’s Rowing, Athletics, Cricket, Sports Overview, Blues & Haigh Awards Additional images (unless credited) 4: Ian Wallman Clubs & Societies ................................................................................22 8, 33: Valerian Chen (2016) Halsbury Society, History Society, Roger Bacon Society, 10, 13, 36, 37, 40, 86, 95, 116: John Cairns (www. Neave Society, Christian Union, Bodley Club, Mathematics Society, johncairns.co.uk) Tinbergen Society 12: Callum Schafer (Mansfield, 2017) 14, 15: Maria Salaru (St Antony’s, 2011) Interdisciplinary Groups ....................................................................32 16, 22, 23, 24, 80: Joseph Rhee (2018) Ockham Lectures, History of the Book Group 28, 32, 99, 103, 104, 108, 109: Timothy Foot -

2014 OBITUARIES Philip German-Ribon

“REQUIEM AETERNAM DONA EIS DOMINE” 2014 OBITUARIES OBITUARIES Philip German-Ribon (30) Philip German- Ribon died on the 16th September aged 101 and at the time of his passing was our oldest OB. He was the youngest of three brothers who came to Beaumont the sons of Roberto. His Grandfather had been the Bolivian Ambassador in London and Paris and he was born in 1912 at their residence in the Cromwell road. Later he moved to Paris and enjoyed holidays at their house in Biarritz. The family were of Spanish origin and there is still a street in Seville named after them but they then moved to Columbia in the 18th century and took part in the liberation of South America with Simon Bolivar; one of Philip’s ancestors was shot by the Spanish as a traitor. In Bolivia they had large mining interests and were involved politically in the administration of the country. Philip though spent most of his childhood in England and his parents had a home near Tunbridge Wells and his father worked in London involved with specialist metals such as bismuth and tin which brought them into involvement with the Wolffs and the London Metal Market. Philip and his brothers were sent to Wagners in Queens Gate where Philip made a strong friendship with John de Laszlo, the son of Philip the society artist. It was during this period that as a young boy Philip visited 11 Downing Street where de Laszlo was painting Sir Austen Chamberlain who also happened also to be a friend of Philip’s parents. -

BWF History Book 2

HISTORY of the BURROUGHS WELLCOME FUND 1955-2005 Celebrating 50 Years of Advancing the Biomedical Sciences HISTORY of the BURROUGHS WELLCOME FUND 1955-2005 Project Coordinator and Editor: Mirinda J. Kossoff Contributing Writers: Tom Burroughs Anastasia Toufexis Book Design: Generate Design ®2005 Historic Preservation Foundation of North Carolina, Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN Number: 0-9673037-0-1 Table of Contents FOREWORD . .1 CHAPTER ONE Sir Henry Wellcome’s Legacy . .4 CHAPTER TWO In the Beginning . .20 CHAPTER THREE Bigger and Better . .32 CHAPTER FOUR Fulfilling the Promise . .46 CHAPTER FIVE Burroughs Wellcome Fund Today . .56 CHAPTER SIX Behind the Scenes . .80 AFTERWORD . .88 BOARD AND STAFF 1955 - 2005 . .90 1955 BWF established as a corporate foundation in Tuckahoe, New York FOREWORD 1955 William N. Creasy appointed first president and board chair 1959 First advisory committee appointed, The Burroughs Wellcome Fund, or BWF as it has become on clinical pharmacology known, is now 50 years old. During the past half century, 1959 First competitive award program launched—Clinical Pharmacology BWF has transformed itself from a small corporate foundation, Scholar Awards 1970 BWF moves to Research Triangle with assets of $160,000 and awards totaling $5,800 in 1955, Park, North Carolina (with Burroughs Wellcome Co.) to a major independent private foundation, with assets in 1971 Dr. George H. Hitchings excess of $650 million and annual awards of more than becomes president $25 million in 2005. In the past decade alone, BWF has made 1974 Iris B. Evans appointed first executive director approximately $250 million in grants. 1978 BWF grantmaking reaches $1 million annually 1979 Toxicology Scholar Awards Through strong, farsighted leadership over the years, program launched BWF has played a significant role in the biomedical sciences 1981 Martha Peck appointed executive director by supporting research and education. -

Blinds & Shutters

GENESIS PUBLICATIONS PROUDLY ANNOUNCE "BLINDS & SHUTTERS - SPECIAL ANNIVERSARY RELEASE’ Blinds & Shutters The Story of the Sixties Michael Cooper www.blindsandshuttersbook.com 'The most stupendous rock and roll picture book ever assembled' – USA Today BLINDS & SHUTTERS is the story of the Sixties, a cult classic and a publishing benchmark. It is quite simply Genesis Publication’s most famous book and widely regarded as the cornerstone of any rock'n'roll library. Now, 30 years after the first copies were produced and to celebrate 45 years in publishing, Genesis is releasing the final 600 copies in the edition, presented in a special anniversary binding. With over 600 photographs and a 30,000-word text from 93 legendary contributors , BLINDS & SHUTTERS is not only a unique insider’s view of the Sixties through the lens of photographer Michael Cooper, it is the defining record of an era, as told by those who were at its centre. From musicians such as Eric Clapton and George Harrison, to artists Andy Warhol and David Hockney, to writers William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, the list of contributors to BLINDS & SHUTTERS is nothing short of awe-inspiring. 50,000 autographs were given during the making of BLINDS & SHUTTERS in 1989; each anniversary copy is signed personally by at least nine of the contributors ( Jump to full list here ) 'Michael had that perfect ability to take all those pictures without annoying anybody. It would be accepted by whoever was around - people wouldn't know they were having their picture taken.' - KEITH RICHARDS Through his association with London's influential art dealer Robert Fraser, the Rolling Stones and The Beatles, Michael Cooper met the artists, writers, poets and musicians of the time as well as the courtiers surrounding them.