The History of Millfield 1935‐1970 by Barry Hobson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

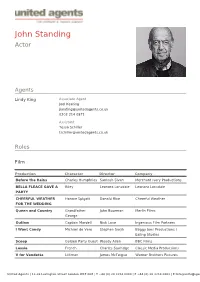

John Standing Actor

John Standing Actor Agents Lindy King Associate Agent Joel Keating [email protected] 0203 214 0871 Assistant Tessa Schiller [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company Before the Rains Charles Humphries Santosh Sivan Merchant Ivory Productions BELLA FLEACE GAVE A Riley Leonora Lonsdale Leonora Lonsdale PARTY CHEERFUL WEATHER Horace Spigott Donald Rice Cheerful Weather FOR THE WEDDING Queen and Country Grandfather John Boorman Merlin Films George Outlaw Captain Mardell Nick Love Ingenious Film Partners I Want Candy Michael de Vere Stephen Surjik Baggy Joes Productions / Ealing Studios Scoop Golden Party Guest Woody Allen BBC Films Lassie French Charles Sturridge Classic Media Productions V for Vendetta Lilliman James McTeigue Warner Brothers Pictures United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company The Best Man Stefan Schwartz Endgame Entertainment Brothers of the Head Keith Fulton & Luis Potboiler Productions / Film4 Pepe Rabbit Fever Ally's Dad Ian Denyer Rabbit Reproductions Ltd Animal Dean Frydman Rose Bosch Studio Legende A Good Woman Dumby Mike Barker Meltemi Entertainment Shoreditch Jenson Thackery Malcolm Needs Bauer Martinez Studios Jack Brown and the Sheldon Gotti Andrew Gilman Curse of the Crown Queen's Messenger Foreign Secretary Mark Roper Boyana Film The Calling Jack Plummer Richard Ceasar Summit Entertainement Mad Cows Politician Sara Sugarman Newmarket Capital -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

The Diary of a West Country Physician, A.D. 1684-1726

Al vi r 22101129818 c Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Wellcome Library https://archive.org/details/b31350914 THE DIARY OF A WEST COUNTRY PHYSICIAN IS A Obi,OJhJf ct; t k 9 5 *fay*/'ckf f?c<uz.s <L<rble> \\M At—r J fF—ojILlIJ- y 't ,-J.M- * - ^jy,-<9. QjlJXy }() * |L Crf fitcJlG-t t $ <z_iedl{£ AU^fytsljc<z.^ act Jfi :tnitutor clout % f §Ve* dtrrt* 7. 5^at~ frt'cUt «k ^—. ^LjHr£hur IW*' ^ (9 % . ' ' ?‘ / ^ f rf i '* '*.<,* £-#**** AT*-/ ^- fr?0- I&Jcsmjl. iLM^i M/n. Jstn**tvn- A-f _g, # ««~Hn^ &"<y muy/*£ ^<u j " *-/&**"-*-■ Ucn^f 3:Jl-y fi//.XeKih>■^':^. li M^^atUu jjm.(rmHjf itftLk*P*~$y Vzmltti£‘tortSctcftuuftriftmu ■i M: Oxhr£fr*fro^^^ J^lJt^ veryf^Jif b^ahtw-* ft^T #. 5£)- (2) rteui *&• ^ y&klL tn £lzJ£xH*AL% S. HjL <y^tdn %^ cfAiAtL- Xp )L ^ 9 $ <£t**$ufl/ Jcjz^, JVJZuil ftjtij ltf{l~ ft Jk^Hdli^hr^ tfitre , f cc»t<L C^i M hrU at &W*&r* &. ^ H <Wt. % fit) - 0 * Cff. yhf£ fdtr tj jfoinJP&*Ji t/ <S m-£&rA tun 9~& /nsJc &J<ztt r£$tr*kt.bJtVYTU( Hr^JtcAjy£,, $ev£%y£ t£* tnjJuk^ THE DIARY OF A WEST COUNTRY PHYSICIAN A.D. 1684-1726 Edited by EDMUND HOBHOUSE, M.D. ‘Medicines ac Musarum Cultor9 TRADE AGENTS: SIMPKIN MARSHALL, LTD. Stationers’ Hall Court, London, E.C.4 PRINTED BY THE STANHOPE PRESS, ROCHESTER *934 - v- p C f, ,s*j FOREWORD The Manuscripts which furnish the material for these pages consist of four large, vellum-bound volumes of the ledger type, which were found by Mr. -

OUTSTANDING SEASONS 2019 PWLTDA %W Sevenoaks School

OUTSTANDING SEASONS 2019 P W L T D A %W Sevenoaks School 14 13 1 5 92.86% Malvern College 19 17 2 3 89.47% Saint John's School Leatherhead 19 17 2 89.47% Shiplake College 16 14 2 2 87.50% Magdalen College School 13 11 2 84.62% Sedbergh School 18 15 3 7 83.33% Harrow School 23 19 3 1 1 82.61% Ratcliffe College 11 9 2 3 81.82% Eastbourne College 20 16 4 1 80.00% Shrewsbury School 24 19 4 1 79.17% Felsted School 19 15 4 78.95% Berkhamsted School 18 14 3 1 1 77.78% Manchester Grammar School (The) 13 10 2 1 4 76.92% Tonbridge School 21 16 2 1 2 2 76.19% Stonyhurst College 4 3 1 4 75.00% Dauntsey's School 20 15 5 1 75.00% Gresham's School 24 18 4 2 75.00% Whitgift School 15 11 3 1 73.33% Dollar Academy 11 8 2 1 6 72.73% Solihull School 11 8 3 3 72.73% Rossall School 7 5 1 1 3 71.43% Haileybury 17 12 3 2 70.59% Clifton College 17 12 3 1 1 2 70.59% King's College, Taunton 20 14 5 1 1 70.00% Dean Close School 10 7 2 1 1 70.00% Bishop's Stortford College 13 9 2 2 69.23% Watford Grammar School for Boys 13 9 3 1 2 69.23% Hampton School 16 11 3 1 1 68.75% Charterhouse 16 11 4 1 2 68.75% Saint Peter's School, York 22 15 5 2 68.18% Ellesmere College 9 6 3 66.67% Birkenhead School 15 10 4 1 66.67% Royal Grammar School, Newcastle 12 8 4 5 66.67% Bede's School 12 8 3 1 66.67% Queen Mary's Grammar School, Walsall 6 4 1 1 3 66.67% Framlingham College 21 14 6 1 1 66.67% Kingswood School 15 10 4 1 66.67% Worksop College 15 10 4 1 5 66.67% Nottingham High School 20 13 6 1 65.00% Millfield School 20 13 7 2 65.00% Bedford School 17 11 3 3 1 64.71% Monmouth School 14 9 5 3 64.29% Lord Wandsworth College 14 9 4 1 64.29% Stamford School 11 7 2 2 3 63.64% George Watson's College 11 7 4 6 63.64% Lancaster Royal Grammar School 19 12 6 1 3 63.16% Oakham School 16 10 5 1 2 62.50% King's School, Macclesfield (The K.S. -

Almanac 2020-21

ALMANAC 2020-21 SCCC Somerset County Cricket Club 2020-2021 2020-2021 The Cooper Associates County Ground, Taunton, Somerset TA1 1JT. Telephone: 01823 425301 Email: [email protected] Website: www.somersetcountycc.co.uk Somerset County Sports Shop: 01823 337597 Centre of Cricketing Excellence: 01823 352266 Somerset Cricket Museum: 01823 275893 Honorary Life Members Contents include: President’s & Chairman’s Reports PW Anderson • Sir Ian Botham Squad Profiles AR Caddick • J Davey Bob Willis Trophy Mrs M Elworthy-Coggan Vitality Blast DJL Gabbitass • J Garner • MF Hill Somerset Cricket Board RC Kerslake • Mrs L Kerslake • MJ Kitchen Including Somerset Age Group, JL Langer • VJ Marks • AT Moulding Youth & Local League Cricket RA O’Donnell • Sir Christopher Ondaatje Obituaries KE Palmer MBE • R Parsons • Sir Viv Richards 2021 Fixtures PJ Robinson • BC Rose • R Snelling CJ Twort • R Virgin • D Wood Editor’s acknowledgements Despite it looking to the contrary for much of the summer in view of the Covid pandemic, cricket was played at all levels in 2020 and within the pages of this publication we have tried to cover as much of it as possible. In the absence of any Second XI cricket and the One Day Cup competition, the Bob Willis Trophy reports have been expanded to include a write up for each day’s play as well as the full scorecards. Sadly all fixtures were played behind closed doors so hopefully these extended reports will enable readers to get the feeling of actually being at the game! In addition, the Somerset Women’s team reports plus the Boys and Girls Pathway write ups are included in the first half of the book as they now come under the remit of Somerset CCC rather than the Somerset Cricket Board. -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

Cricket Memorabilia Society Postal Auction Closing at Noon 10

CRICKET MEMORABILIA SOCIETY POSTAL AUCTION CLOSING AT NOON 10th JULY 2020 Conditions of Postal Sale The CMS reserves the right to refuse items which are damaged or unsuitable, or we have doubts about authenticity. Reserves can be placed on lots but must be agreed with the CMS. They should reflect realistic values/expectations and not be the “highest price” expected. The CMS will take 7% of the price realised, the vendor 93% which will normally be paid no later than 6 weeks after the auction. The CMS will undertake to advertise the memorabilia for auction on its website no later than 3 weeks prior to the closing date of the auction. Bids will only be accepted from CMS members. Postal bids must be in writing or e-mail by the closing date and time shown above. Generally, no item will be sold below 10% of the lower estimate without reference to the vendor.. Thus, an item with a £10-15 estimate can be sold for £9, but not £8, without approval. The incremental scale for the acceptance of bids is as follows: £2 increments up to £20, then £20/22/25/28/30 up to £50, then £5 increments to £100 and £10 increments above that. So, if there are two postal bids at £25 and £30, the item will go to the higher bidder at £28. Should there be two identical bids, the first received will win. Bids submitted between increments will be accepted, thus a £52 bid will not be rounded either up or down. Items will be sent to successful postal bidders the week after the auction and will be sent by the cheapest rate commensurate with the value and size of the item. -

November 2014

FREE November 2014 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME www.worldrugby.bm GOLF TouRNAMENt REFEREEs LIAIsON Michael Jenkins Derek Bevan mbe • John Weale GROuNds RuCK & ROLL FRONt stREEt Cameron Madeiros • Chris Finsness Ronan Kane • Jenny Kane Tristan Loescher Michael Kane Trevor Madeiros (National Sports Centre) tEAM LIAIsONs Committees GRAPHICs Chief - Pat McHugh Carole Havercroft Argentina - Corbus Vermaak PREsIdENt LEGAL & FINANCIAL Canada - Jack Rhind Classic Lions - Simon Carruthers John Kane, mbe Kim White • Steve Woodward • Ken O’Neill France - Marc Morabito VICE PREsIdENt MEdICAL FACILItIEs Italy - Guido Brambilla Kim White Dr. Annabel Carter • Dr. Angela Marini New Zealand - Brett Henshilwood ACCOMMOdAtION Shelley Fortnum (Massage Therapists) South Africa - Gareth Tavares Hilda Matcham (Classic Lions) Maureen Ryan (Physiotherapists) United States - Craig Smith Sue Gorbutt (Canada) MEMbERs tENt TouRNAMENt REFEREE AdMINIstRAtION Alex O'Neill • Rick Evans Derek Bevan mbe Julie Butler Alan Gorbutt • Vicki Johnston HONORARy MEMbERs CLAssIC CLub Harry Patchett • Phil Taylor C V “Jim” Woolridge CBE Martine Purssell • Peter Kyle MERCHANdIsE (Former Minister of Tourism) CLAssIC GAs & WEbsItE Valerie Cheape • Debbie DeSilva Mike Roberts (Wales & the Lions) Neil Redburn Allan Martin (Wales & the Lions) OVERsEAs COMMENtARy & INtERVIEWs Willie John McBride (Ireland & the Lions) Argentina - Rodolfo Ventura JPR Williams (Wales & the Lions) Hugh Cahill (Irish Television) British Isles - Alan Martin Michael Jenkins • Harry Patchett Rodolfo Ventura (Argentina) -

The Great War, 1914-18 Biographies of the Fallen

IRISH CRICKET AND THE GREAT WAR, 1914-18 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE FALLEN BY PAT BRACKEN IN ASSOCIATION WITH 7 NOVEMBER 2018 Irish Cricket and the Great War 1914-1918 Biographies of The Fallen The Great War had a great impact on the cricket community of Ireland. From the early days of the war until almost a year to the day after Armistice Day, there were fatalities, all of whom had some cricket heritage, either in their youth or just prior to the outbreak of the war. Based on a review of the contemporary press, Great War histories, war memorials, cricket books, journals and websites there were 289 men who died during or shortly after the war or as a result of injuries received, and one, Frank Browning who died during the 1916 Easter Rising, though he was heavily involved in organising the Sporting Pals in Dublin. These men came from all walks of life, from communities all over Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka. For all but four of the fifty-two months which the war lasted, from August 1914 to November 1918, one or more men died who had a cricket connection in Ireland or abroad. The worst day in terms of losses from a cricketing perspective was the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, when eighteen men lost their lives. It is no coincidence to find that the next day which suffered the most losses, 9 September 1916, at the start of the Battle of Ginchy when six men died. -

FOI 114/11 Crimes in Schools September 2010 – February 2011

FOI 114/11 Crimes in Schools September 2010 – February 2011 Incident Premisies Name Town / City Current Offence Group Count Abbeywood Community School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 4 Alexandra Park Beechen Cliff School Bath Criminal Damage 1 Alexandra Park Beechen Cliff School Bath Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 4 Alexandra Park Beechen Cliff School Bath Violence Against The Person 1 Allen School House Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 0 Archbishop Cranmer Community C Of E School Taunton Burglary 1 Ashcombe Cp School Weston-Super-Mare Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 2 Ashcombe Primary School Weston-Super-Mare Violence Against The Person 0 Ashcott Primary School Bridgwater Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 0 Ashill Primary School Ilminster Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Ashley Down Infant School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 2 Ashton Park School Bristol Other Offences 1 Ashton Park School Bristol Sexual Offences 1 Ashton Park School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Avon Primary School Bristol Burglary 2 Backwell School Bristol Burglary 3 Backwell School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Backwell School Bristol Violence Against The Person 1 Badminton School Bristol Violence Against The Person 0 Banwell Primary School Banwell Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Bartletts Elm School Langport Criminal Damage 0 Barton Hill County Infant School & Nursery Bristol Burglary 1 Barton Hill Primary School Bristol Violence Against The Person 0 Barwick Stoford Pre School Yeovil Fraud Forgery 1 Batheaston Primary -

A M D G Beaumont Union Review Summer 2020

A M D G BEAUMONT UNION REVIEW SUMMER 2020 "And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year: ―Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.‖ Well, we didn‘t see this one coming. Having written in the last REVIEW about ―a year like no other‖ which concludes in this Edition, no one thought we would be living through another. Over 90% of the BU have been confined and we have seen the cancellation of The HCPT and BOFs Pilgrimage to Lourdes, The Verdun Battlefield Tour, The BUGS Meeting at Westerham and Ant Stevens much anticipated Musical ―Streetwise‖: Now rescheduled for 24-29 May 2021. Much quoted at the moment ―We will meet again, Don‘t know where, Don‘t know when but I know we will meet again some sunny day: - Actually it looks like a cloudy day in the Autumn if we are lucky! I was amazed by the response to my Easter Message: I don‘t know whether it could be described as an ―Urbi et Orbi‖ moment but it did bring a huge response from OBs worldwide. One such from Patrick Agnew which I share with you:- ―Indeed. We have taken a lot for granted, during our years; much to be grateful for. Humanity is vulnerable to many things, some much worse than seen now. Globalization has it‘s many drawbacks, as well. Our precious little planet, in such perfect evolved balance, for so many eons, is also threatened by the economic ―progress‖ of mankind, whose numbers compound upwards and ravage resources, and are poisoning them. -

The Ampleforth Journal September 2018 to July 2019

The Ampleforth Journal September 2018 to July 2019 Volume 123 4 THE AMPLEFORTH JOURNAL VOL 123 Contents editorial 6 the ampleforth Community 8 the aims of arCiC iii 10 Working within the United nations Civil affairs department 17 Peace and security in a fractured world 22 My ampleforth connection 27 Being a Magistrate was not for me 29 the new testament of the revised new Jerusalem Bible 35 the ampleforth Gradual 37 the shattering of lonliness 40 Family of the raj by John Morton (C55) 42 right money, right place, right time by Jeremy deedes (W73) 44 the land of the White lotus 46 the Waterside ape by Peter rhys evans (H66) 50 Fr dominic Milroy osB 53 Fr aidan Gilman osB 58 Fr Cyprian smith osB 64 Fr antony Hain osB 66 Fr thomas Cullinan osB 69 richard Gilbert 71 old amplefordian obituaries 73 CONTENTS 5 editorial Fr riCHard FField osB editor oF tHe aMPleFortH JoUrnal here have been various problems with the publishing of the ampleforth Journal and, with the onset of the corona virus we have therefore decided to publish this issue online now without waiting for the printed edition. With the closure of churches it is strange to be celebrating Mass and singing the office each day in our empty abbey Church but we are getting daily emails from people who are appreciating the opportunity to listen to our Mass and office through the live streaming accessible from our website. on sunday, 15th March, about a hundred tuned in; a week later, there were over a thousand.