Show Me the Money: Characterizing Spam-Advertised Revenue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Advertising

Online advertising From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. (July 2007) Electronic commerce Online goods and services Streaming media Electronic books Software Retail product sales Online shopping Online used car shopping Online pharmacy Retail services Online banking Online food ordering Online flower delivery Online DVD rental Marketplace services Online trading community Online auction business model Online wallet Online advertising Price comparison service E-procurement This box: view • talk • edit Online advertising is a form of advertising that uses the Internet and World Wide Web in order to deliver marketing messages and attract customers. Examples of online advertising include contextual ads on search engine results pages, banner ads, advertising networks and e-mail marketing, including e-mail spam. A major result of online advertising is information and content that is not limited by geography or time. The emerging area of interactive advertising presents fresh challenges for advertisers who have hitherto adopted an interruptive strategy. Online video directories for brands are a good example of interactive advertising. These directories complement television advertising and allow the viewer to view the commercials of a number of brands. If the advertiser has opted for a response feature, the viewer may then choose to visit the brand’s website, or interact with the advertiser through other touch points such as email, chat or phone. Response to brand communication is instantaneous, and conversion to business is very high. This is because in contrast to conventional forms of interruptive advertising, the viewer has actually chosen to see the commercial. -

Zambia and Spam

ZAMNET COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS LTD (ZAMBIA) Spam – The Zambian Experience Submission to ITU WSIS Thematic meeting on countering Spam By: Annabel S Kangombe – Maseko June 2004 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 What is spam? 1 1.2 The nature of Spam 1 1.3 Statistics 2 2.0 Technical view 4 2.1 Main Sources of Spam 4 2.1.1 Harvesting 4 2.1.2 Dictionary Attacks 4 2.1.3 Open Relays 4 2.1.4 Email databases 4 2.1.5 Inadequacies in the SMTP protocol 4 2.2 Effects of Spam 5 2.3 The fight against spam 5 2.3.1 Blacklists 6 2.3.2 White lists 6 2.3.3 Dial‐up Lists (DUL) 6 2.3.4 Spam filtering programs 6 2.4 Challenges of fighting spam 7 3.0 Legal Framework 9 3.1 Laws against spam in Zambia 9 3.2 International Regulations or Laws 9 3.2.1 US State Laws 9 3.2.2 The USA’s CAN‐SPAM Act 10 4.0 The Way forward 11 4.1 A global effort 11 4.2 Collaboration between ISPs 11 4.3 Strengthening Anti‐spam regulation 11 4.4 User education 11 4.5 Source authentication 12 4.6 Rewriting the Internet Mail Exchange protocol 12 1.0 Introduction I get to the office in the morning, walk to my desk and switch on the computer. One of the first things I do after checking the status of the network devices is to check my email. -

Email Phishing for IT Providers How Phishing Emails Have Changed and How to Protect Your IT Clients

Email Phishing for IT Providers How phishing emails have changed and how to protect your IT clients 1 © 2016 Calyptix Security Corporation. All rights reserved. I [email protected] I (800) 650 – 8930 (800) 650-8930 I [email protected] Contents Introduction ............................................................................................ 2 Phishing overview .................................................................................. 3 Trends in phishing emails ...................................................................... 6 Email phishing tactics .......................................................................... 11 Steps for MSP & VARS .......................................................................... 24 Advice for your clients .......................................................................... 29 Sources .................................................................................................. 35 1 © 2016 Calyptix Security Corporation. All rights reserved. I [email protected] I (800) 650 – 8930 Introduction There are only so many ways to break into a bank. You can march through the door. You can climb through a window. You can tunnel through the floor. There is the service entrance, the employee entrance, and access on the roof. Criminals who want to rob a bank will probably use an open route – such as a side door. It’s easier than breaking down a wall. Criminals who want to break into your network face a similar challenge. They need to enter. They can look for a weakness in your -

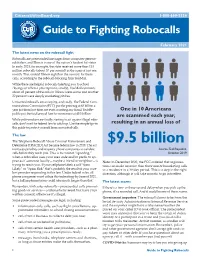

CUB Guide to Fighting Robocalls

CitizensUtilityBoard.org 1-800-669-5556 Guide to Fighting Robocalls February 2021 The latest news on the robocall fi ght Robocalls are prerecorded messages from computer-generat- ed dialers, and Illinois is one of the nation’s hardest hit states. In early 2021, for example, the state received more than 153 million robocalls (about 57 per second) in the span of just one month. That ranked Illinois eighth in the country for these calls, according to the robocall-blocking fi rm YouMail. While there are helpful robocalls (alerting you to school closings or when a prescription is ready), YouMail estimates about 42 percent of the calls in Illinois were scams and another 22 percent were simply marketing pitches. Unwanted robocalls are annoying, and costly. The Federal Com- munications Commission (FCC) put the price tag at $3 billion a year just from lost time, not even counting any fraud. TechRe- One in 10 Americans public put the total annual loss for consumers at $9.5 billion. are scammed each year, While policymakers are fi nally starting to act against illegal robo- calls, don’t wait for federal law to catch up. Use the simple tips in resulting in an annual loss of this guide to protect yourself from unwanted calls. The law The Telephone Robocall Abuse Criminal Enforcement and $9.5 billion Deterrence (TRACED) Act became federal law in 2019. The act increases penalties and requires phone companies to validate Source: TechRepublic, calls before they reach you. This is to combat “spoofi ng,” October 2019 when a robocaller uses your area code and/or prefi x to ap- pear as if someone locally—maybe a friend or neighbor—is Note: In December 2020, the FCC ordered that organiza- trying to reach you. -

Locating Spambots on the Internet

BOTMAGNIFIER: Locating Spambots on the Internet Gianluca Stringhinix, Thorsten Holzz, Brett Stone-Grossx, Christopher Kruegelx, and Giovanni Vignax xUniversity of California, Santa Barbara z Ruhr-University Bochum fgianluca,bstone,chris,[email protected] [email protected] Abstract the world-wide email traffic [20], and a lucrative busi- Unsolicited bulk email (spam) is used by cyber- ness has emerged around them [12]. The content of spam criminals to lure users into scams and to spread mal- emails lures users into scams, promises to sell cheap ware infections. Most of these unwanted messages are goods and pharmaceutical products, and spreads mali- sent by spam botnets, which are networks of compro- cious software by distributing links to websites that per- mised machines under the control of a single (malicious) form drive-by download attacks [24]. entity. Often, these botnets are rented out to particular Recent studies indicate that, nowadays, about 85% of groups to carry out spam campaigns, in which similar the overall spam traffic on the Internet is sent with the mail messages are sent to a large group of Internet users help of spamming botnets [20,36]. Botnets are networks in a short amount of time. Tracking the bot-infected hosts of compromised machines under the direction of a sin- that participate in spam campaigns, and attributing these gle entity, the so-called botmaster. While different bot- hosts to spam botnets that are active on the Internet, are nets serve different, nefarious goals, one important pur- challenging but important tasks. In particular, this infor- pose of botnets is the distribution of spam emails. -

The History of Spam Timeline of Events and Notable Occurrences in the Advance of Spam

The History of Spam Timeline of events and notable occurrences in the advance of spam July 2014 The History of Spam The growth of unsolicited e-mail imposes increasing costs on networks and causes considerable aggravation on the part of e-mail recipients. The history of spam is one that is closely tied to the history and evolution of the Internet itself. 1971 RFC 733: Mail Specifications 1978 First email spam was sent out to users of ARPANET – it was an ad for a presentation by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) 1984 Domain Name System (DNS) introduced 1986 Eric Thomas develops first commercial mailing list program called LISTSERV 1988 First know email Chain letter sent 1988 “Spamming” starts as prank by participants in multi-user dungeon games by MUDers (Multi User Dungeon) to fill rivals accounts with unwanted electronic junk mail. 1990 ARPANET terminates 1993 First use of the term spam was for a post from USENET by Richard Depew to news.admin.policy, which was the result of a bug in a software program that caused 200 messages to go out to the news group. The term “spam” itself was thought to have come from the spam skit by Monty Python's Flying Circus. In the sketch, a restaurant serves all its food with lots of spam, and the waitress repeats the word several times in describing how much spam is in the items. When she does this, a group of Vikings in the corner start a song: "Spam, spam, spam, spam, spam, spam, spam, spam, lovely spam! Wonderful spam!" Until told to shut up. -

Proceedings of the 67Th Annual Session of the ASHP House Of

House of Delegates Session—2015 June 7 and 9, 2015 Denver, Colorado Proceedings of the 67th annual session of the ASHP House of Delegates, June 7 and 9, 2015 Proceedings of the 67th annual session of the ASHP House of Delegates, June 7 and 9, 2015 PAUL W. ABRAMOWITZ, SECRETARY The 67th annual session of the ASHP House of Delegates was James A. Trovato, Pharm.D., M.B.A., BCOP, FASHP, Associ- held at the Colorado Convention Center, in Denver, Colorado, ate Professor, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, in conjunction with the 2015 Summer Meetings. Baltimore, MD First meeting Chair, House of Delegates 2015–2018 Amber J. Lucas, Pharm.D., BCPS, FASHP, Clinical Pharmacist, The first meeting was convened at 1:00 p.m. Sunday, June 7, Olathe Medical Center, Olathe, KS by Chair of the House of Delegates James A. Trovato. Chair Trovato introduced the persons seated at the head table: Gerald Natasha Nicol, Pharm.D., FASHP, Director of Global Patient E. Meyer, Immediate Past President of ASHP and Vice Chair Safety Affairs, Cardinal Health, Pawleys Island, SC of the House of Delegates; Christene M. Jolowsky, President of ASHP and Chair of the Board of Directors; Paul W. Abramowitz, Board of Directors, 2016–2019 Chief Executive Officer of ASHP and Secretary of the House of Debra L. Cowan, Pharm.D., FASHP, Director of Pharmacy, Delegates; and Susan Eads Role, Parliamentarian. Angel Medical Center, Franklin, NC Todd A. Karpinski, Pharm.D., M.S., FASHP, Chief Phar- Chair Trovato welcomed the delegates and described the macy Officer, Froedtert and the Medical College of Wisconsin, purposes and functions of the House. -

Addresses of Record Not on Internet

Newsletter Indexfrom July 1998 through March 2013 Abandonment of Application Files 07/2007 Addresses of Record to go Online 04/2000 Addresses of Record Will Not go Online 07/2000 Addresses of Record to go Online 10/2003 Addresses of Record Important 01/2010 Addresses of Record Important 03/2012 Ambulance Restocking 01/2001 Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004 09/2006 Anthrax Q & A 10/2001 APAP/NSAIDs on Container Labels 03/2012 Automated Drug Delivery Systems 01/2007 Automated Drug Dispensing Services 01/2002 Automated Systems in SNF/ICF 01/2005 Automation/Robotic Dispensing Check by RPH 01/2005 Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Med 03/2013 Use in Older Adults Black Box Warnings 01/2007 Board Enforces QAP and Urges Med Error Reporting 07/2007 Board Honors 50-Years Pharmacists (Ongoing) 10/2005 Board Inspectors/Verify ID 01/2010 Board Office Closed Two Days per Month 02/2009 Board Office Closed Three Days per Month 01/2010 Board Website Online 07/2000 Board Wins 5th National Award in Eight Years 10/2005 Board’s 110th Anniversary 04/2001 Board’s Budget Woes Curtails Services 01/2002 Board’s New Address/Phone Numbers 01/2006 Board Reappointments 03/2012 Board’s Web Site Info 10/2003 Boxed Warning Medications 01/2008 Brooks, Ryan/New Public Member 02/2009 BTC Drug Category Explored 01/2008 Canadian Drug Imports 03/2003 California Pharmacists Who Participate in Torture 02/2009 Carisoprodol Now Schedule IV 03/2012 Cash Compromise is Unprofessional Conduct 01/2002 Cathine Added to Schedule IV 02/2009 Cathinone Added to Schedule II -

E-Pharmacy Regulations in India: Past, Present, and Future Priya Nair S

S. Priya Nair, Middha Anil; International Journal of Advance Research, Ideas and Innovations in Technology ISSN: 2454-132X Impact factor: 4.295 (Volume 5, Issue 1) Available online at: www.ijariit.com E-Pharmacy regulations in India: Past, present, and future Priya Nair S. Dr. Anil Middha [email protected] [email protected] OPJS University, Churu, Rajasthan OPJS University, Churu, Rajasthan ABSTRACT The advent of digitalization has taken India by storm and the pharma sector is also not left behind. The trend of purchasing medicine online is increasing and so is the number of e-pharmacy start-ups. E- Pharmacies are recent entrants in the Indian e-commerce industry and receiving attention from the government as well as global investors from the past three years. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India has published draft rules on 28th August 2018, with the heading “Sale of drugs by e-pharmacy” to bring e-pharmacies within the scope of Drug and Cosmetics Rules, 1945 by making amendments in it which currently does not distinguish between online and brick and mortar pharmacies. It aims to regulate online sale of quality medicines pan India through e-pharmacies registered under Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), India’s apex drug regulator and central licensing authority, where all records are maintained as per rules laid down. The confidentiality of patient details have to be maintained and cannot be disclosed to anyone one under any circumstances other than the central or state government as the case may be. The sale of tranquillizers, narcotic and psychotropic substances and Schedule X drugs are not permitted through e- pharmacies. -

Everything You Need to Know About Becoming a Pharmacy Technician

Everything You Need to Know About Becoming a Pharmacy Technician If you’re searching for a rewarding career that allows you to help others, becoming a pharmacy technician is something you might not have looked into before. However, there’s a lot to know about starting a new career path and you may not have had time to research as much as you’d like. Before you decide to put off your career goals even longer, take a look at everything you need to know about becoming a pharmacy technician right in one place! What Does a Pharmacy Technician do? Pharmacy technicians work with pharmacists to dispense prescription medications to patients and health professionals. Typically, a trained pharmacy technician will be responsible for a number of tasks throughout their workday, some of which can vary based on their workplace. As a pharmacy technician, it will be your job to collect information from customers and doctors so you can give the right prescriptions to the right patients. Under the direction of a licensed pharmacist, you’ll measure, package, label and inventory medications. You’ll work with the pharmacist and other pharmacy technicians to quickly and correctly prepare all medications. Entering customer information into computers and accepting payment for prescriptions will also be part of your job. One of your big responsibilities will be keeping information organized and confidential. Customers will rely on you to answer their questions and give them information both over the phone and in person. In many cases, customers will talk to you first before talking to the pharmacist. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Characterizing Robocalls Through Audio and Metadata Analysis

Who’s Calling? Characterizing Robocalls through Audio and Metadata Analysis Sathvik Prasad, Elijah Bouma-Sims, Athishay Kiran Mylappan, and Bradley Reaves, North Carolina State University https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity20/presentation/prasad This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium. August 12–14, 2020 978-1-939133-17-5 Open access to the Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX. Who’s Calling? Characterizing Robocalls through Audio and Metadata Analysis Sathvik Prasad Elijah Bouma-Sims North Carolina State University North Carolina State University [email protected] [email protected] Athishay Kiran Mylappan Bradley Reaves North Carolina State University North Carolina State University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Despite the clear importance of the problem, much of what Unsolicited calls are one of the most prominent security is known about the unsolicited calling epidemic is anecdotal issues facing individuals today. Despite wide-spread anec- in nature. Despite early work on the problem [6–10], the re- dotal discussion of the problem, many important questions search community still lacks techniques that enable rigorous remain unanswered. In this paper, we present the first large- analysis of the scope of the problem and the factors that drive scale, longitudinal analysis of unsolicited calls to a honeypot it. There are several challenges that we seek to overcome. of up to 66,606 lines over 11 months. From call metadata we First, we note that most measurements to date of unsolicited characterize the long-term trends of unsolicited calls, develop volumes, trends, and motivations (e.g., sales, scams, etc.) have the first techniques to measure voicemail spam, wangiri at- been based on reports from end users.