Recovery of the Rockaways: an Analysis of the Role of Cultural Resources in Public Policy After Hurricane Sandy and Its Effect on Community Resilience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4/8/69 #778 Miss Harlem Beauty Contest Applications Available #779 19Th Annual Valentines Day Winter Ca

W PRESSRELEASES 2/7/69 - 4/8/69 #778 Miss Harlem Beauty Contest Applications Available #779 19th Annual Valentines Day Winter Carnival In Queens (Postponed Until Friday, February 21, 1969) #780 Police Public Stable Complex, 86th St., Transverse, Central Park #781 Monday, March 10th, Opening Date For Sale of Season Golf Lockers and Tennis Permits #782 Parks Cited For Excellence of Design #783 New York City's Trees Badly Damaged During Storm #784 Lifeguard Positions Still Available #785 Favored Knick To Be Picked #786 Heckschers Cutbacks In State Aid to the City #787 Young Chess Players to Compete #788 r Birth of Lion and Lamb #789 Jones Gives Citations at Half Time (Basketball) #790 Nanas dismantled on March 27, 1969 #791 Birth of Aoudad in Central Park Zoo #792 Circus Animals to Stroll in Park #793 Richmond Parkway Statement #794 City Golf Courses, Lawn Bowling and Croquet Cacilities Open #795 Eggs-Egg Rolling - Several Parks #796 Fifth Annual Golden Age Art Exhibition #797 Student Sculpture Exhibit In Central Park #798 Charley the Mule Born March 27 in Central Park Zoo #799 Rain date for Easter Egg Rolling contest April 12, original date above #800 Sculpture - Central Park - April 10 2 TOTAL ESTIMATED ^DHSTRUCTION COST: $5.1 Million DESCRIPTION: Most of the facilities will be underground. Ground-level rooftops will be planted as garden slopes. The stables will be covered by a tree orchard. There will be panes of glass in long shelters above ground so visitors can watch the training and stabling of horses in the underground facilities. Corrals, mounting areas and exercise yards, for both public and private use, will be below grade but roofless and open for public observation. -

2008 Inventory Location Maps

2008 INVENTORY LOCATION MAPS Eight years ago, we added a new feature to the Inventory Location Maps; Community Board borders. With this added feature, the reader will be able to identify within which Community Boards bridges are located. On these maps, all Community Boards consist of three (3) digits. The first digit is for map plotting purposes. The next two digits identify the Community Board. In cases of certain parks and airports, the Community Board number does not correspond with any Community Board. These exceptions are: Bronx 26=Van Cortlandt Park Brooklyn 55=Prospect Park 27=Bronx Park 56=Gateway Nat’l Rec. Area/Floyd Bennett Field 28=Pelham Bay Park Queens 80=La Guardia Airport Manhattan 64= Central Park 81=Alley Pond Park 82=Cunningham Park 83=JFK Airport 84= Gateway Nat’l Rec. Area/Fort Tilden-Jacob Riis Park The Community Board listings correspond to those listed in the inventory, which begins on page 209. Some structures fall on Community Board dividing lines: their additional Community Boards are now identified in the inventory in columns CD2 and CD3. Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg Bridges. (Credit: Michele N. Vulcan) 313 2008 BRIDGES AND TUNNELS ANNUAL CONDITION REPORT ALL BOROUGHS Bronx Manhattan Queens Brooklyn Staten Island Legend BOROUGHS Central Park Brooklyn Manhattan Queens Staten Island 0 8,000 16,000 32,000 48,000 64,000 The Bronx Feet Scale BROOKLYN Pulaski Bridge 2240639 KOSCIUSZKO Williamsburg MANHATTAN BRIDGE AVENUE 2240370 Manhattan Bridge Bridge BQE See Brooklyn 2240027 2240028 301 2240390 CB 302, -

To Download Three Wonder Walks

Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) Featuring Walking Routes, Collections and Notes by Matthew Jensen Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) The High Line has proven that you can create a des- tination around the act of walking. The park provides a museum-like setting where plants and flowers are intensely celebrated. Walking on the High Line is part of a memorable adventure for so many visitors to New York City. It is not, however, a place where you can wander: you can go forward and back, enter and exit, sit and stand (off to the side). Almost everything within view is carefully planned and immaculately cultivated. The only exception to that rule is in the Western Rail Yards section, or “W.R.Y.” for short, where two stretch- es of “original” green remain steadfast holdouts. It is here—along rusty tracks running over rotting wooden railroad ties, braced by white marble riprap—where a persistent growth of naturally occurring flora can be found. Wild cherry, various types of apple, tiny junipers, bittersweet, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, mullein, Indian hemp, and dozens of wildflowers, grasses, and mosses have all made a home for them- selves. I believe they have squatters’ rights and should be allowed to stay. Their persistence created a green corridor out of an abandoned railway in the first place. I find the terrain intensely familiar and repre- sentative of the kinds of landscapes that can be found when wandering down footpaths that start where streets and sidewalks end. This guide presents three similarly wild landscapes at the beautiful fringes of New York City: places with big skies, ocean views, abun- dant nature, many footpaths, and colorful histories. -

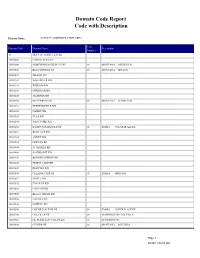

Domain Code Report Code with Description

Domain Code Report Code with Description Element Name: AGENCY ADMINISTRATIVE AREA Line Domain Code Domain Name Description Number 10 DEPT OF AGRICULTURE 10000000 FOREST SERVICE 10010000 NORTHERN REGION USFS 01 MONTANA MISSOULA 10010200 BEAVERHEAD NF 01 MONTANA DILLON 10010201 DILLON RD 10010202 WISE RIVER RD 10010203 WISDOM RD 10010206 SHERIDAN RD 10010207 MADISON RD 10010300 BITTERROOT NF 01 MONTANA HAMILTON 10010301 STEVENSVILLE RD 10010302 DARBY RD 10010303 SULA RD 10010304 WEST FORK RD 10010400 IDAHO PANHANDLE NF 01 IDAHO COEUR D ALENE 10010401 WALLACE RD 10010402 AVERY RD 10010403 FERNAN RD 10010404 ST MARIES RD 10010406 SANDPOINT RD 10010407 BONNERS FERRY RD 10010408 PRIEST LAKE RD 10010409 RED IVES RD 10010500 CLEARWATER NF 01 IDAHO OROFINO 10010501 PIERCE RD 10010502 PALOUSE RD 10010503 CANYON RD 10010504 KELLY CREEK RD 10010505 LOCHSA RD 10010506 POWELL RD 10010600 COEUR D ALENE NF 01 IDAHO COEUR D ALENE 10010700 COLVILLE NF 01 WASHINGTON COLVILLE 10010710 NE WASH LUP (COLVILLE) 01 WASHINGTON 10010800 CUSTER NF 01 MONTANA BILLINGS Page 1 09/20/11 02:07 PM Line Domain Code Domain Name Description Number 10010801 SHEYENNE RD 10010802 BEARTOOTH RD 10010803 SIOUX RD 10010804 ASHLANDFORT HOWES RD 10010806 GRAND RIVER RD 10010807 MEDORA RD 10010808 MCKENZIE RD 10010810 CEDAR RIVER NG 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010820 DAKOTA PRAIRIES GRASSLAND 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010830 SHEYENNE NG 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010840 GRAND RIVER NG 01 SOUTH DAKOTA 10010900 DEERLODGE NF 01 MONTANA BUTTE 10010901 DEER LODGE RD 10010902 JEFFERSON RD 10010903 PHILIPSBURG RD 10010904 BUTTE RD 10010929 DILLON RD 01 MONTANA DILLON 11 LANDS IN BUTTE RD, DEERLODGE NF ADMIN 12 ISTERED BY THE DILLON RD, BEAVERHEAD NF. -

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014 Social Assessment White Paper No. 2 March 2016 Prepared by: D. S. Novem Auyeung Lindsay K. Campbell Michelle L. Johnson Nancy F. Sonti Erika S. Svendsen Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 8 Study Area ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Collection .................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Analysis........................................................................................................................................ 15 Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 16 Park Profiles ........................................................................................................................................ -

Epilogue 1941—Present by BARBARA LA ROCCO

Epilogue 1941—Present By BARBARA LA ROCCO ABOUT A WEEK before A Maritime History of New York was re- leased the United States entered the Second World War. Between Pearl Harbor and VJ-Day, more than three million troops and over 63 million tons of supplies and materials shipped overseas through the Port. The Port of New York, really eleven ports in one, boasted a devel- oped shoreline of over 650 miles comprising the waterfronts of five boroughs of New York City and seven cities on the New Jersey side. The Port included 600 individual ship anchorages, some 1,800 docks, piers, and wharves of every conceivable size which gave access to over a thousand warehouses, and a complex system of car floats, lighters, rail and bridge networks. Over 575 tugboats worked the Port waters. Port operations employed some 25,000 longshoremen and an additional 400,000 other workers.* Ships of every conceivable type were needed for troop transport and supply carriers. On June 6, 1941, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 84 vessels of foreign registry in American ports under the Ship Requisition Act. To meet the demand for ships large numbers of mass-produced freight- ers and transports, called Liberty ships were constructed by a civilian workforce using pre-fabricated parts and the relatively new technique of welding. The Liberty ship, adapted by New York naval architects Gibbs & Cox from an old British tramp ship, was the largest civilian- 262 EPILOGUE 1941 - PRESENT 263 made war ship. The assembly-line production methods were later used to build 400 Victory ships (VC2)—the Liberty ship’s successor. -

32 City Council District Profiles

QUEENS CITY Woodhaven, Ozone Park, Lindenwood, COUNCIL 2009 DISTRICT 32 Howard Beach, South Ozone Park Parks are an essential city service. They are the barometers of our city. From Flatbush to Flushing and Morrisania to Midtown, parks are the front and backyards of all New Yorkers. Well-maintained and designed parks offer recreation and solace, improve property values, reduce crime, and contribute to healthy communities. SHOWCASE : Rockaway Beach The Report Card on Beaches is modeled after New Yorkers for Parks’ award-winning Report Card on Parks. Through the results of independent inspections, it tells New Yorkers how well the City’s seven beaches are maintained in four key service areas: shorelines, pathways, bathrooms, and drink- ing fountains. The Report Card on Beaches is an effort to highlight these important facilities and ensure that New York City’s 14 miles of beaches are open, clean, and safe. Rockaway Beach is Police Officer Nicholas DeMutiis Playground, Ozone Park one of the seven public beaches The Bloomberg Administration’s physical barriers or crime. As a result, owned and operated by the City’s Parks Department. In 2007, PlaNYC is the first-ever effort to studies show significant increases in this beach was rated “challenged.” sustainably address the many infra- nearby real estate values. Greenways Its shoreline was impacted by structure needs of New York City, are expanding waterfront access broken glass. Visit www.ny4p.org including parks. With targets set for while creating safer routes for cyclists for more information on the stormwater management, air quality and pedestrians, and the new initia- Report Card on Beaches. -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other. -

Total Population by Census Tract Bronx, 2010

PL-P1 CT: Total Population by Census Tract Bronx, 2010 Total Population 319 8,000 or more 343 6,500 to 7,999 5,000 to 6,499 337 323 345 414 442 3,500 to 4,999 451.02 444 2,500 to 3,499 449.02 434 309 449.01 451.01 418 436 Less than 2,500 351 435 448 Van Cortlandt Park 428 420 430 H HUDSONPKWY 307.01 BROADWAY 422 426 335 408 424 456 406 285 394 484 295 I 87 MOSHOLU PKWY 404 458 283 297 396 281 301 431 392 287 279 398 460 BRONX RIVER PKWY 293.01 421 390 293.02 289 378 388 386 277 462.02 504 Pelham Bay Park 380 409 423 429.02 382 419 411 368 376 374 462.01 273 413 429.01 372 364 358 370 267.02 407.01 425 415 267.01 403.03 407.02 348 403.02 336 338 340 342 344 350 403.04 405.01 360 356 DEEGAN EXWY 261 265 405.02 269 263 401 399.01 332.02 W FORDHAM RD 397 316 312 302 E FORDHAM RD 330 328 324 326 318 314 237.02 310 257 253 399.02 255 237.03 334 332.01 239 HUTCHINSON RIVER PKWY 387 Botanical Gardens 249 383.01383.02 Bronx Park BX AND PELHAM PKWY 247 251 224.03 237.04 385 389 245.02 224.01 248 296 288 Hart Island 228 276 Cemetery 245.01 243 241235.01 391 224.04 53 393 250 300 235.02381 379 375.04 205.02 246 215.01 233.01 286 284 373 230 205.01 233.02 395 254 215.02 266.01 227.01 371 232 252 516 229.01 231 244 266.02 213.01 217 236 CROSS BRONX EXWY 365.01 227.02 369.01 363 256 229.02 238 213.02 209 227.03 165 200 BRUCKNER EXWY 201 369.02 365.02 361 274.01 240 264 367 220 210.01 204 211 223 225 171 167 359 219 163 274.02 221.01 169 Crotona Park 210.02 202 193 221.02 60 218 216.01 184 161 216.02 199 179.02 147.02 212 206.01 177.02 155 222 197 179.01 96 147.01 194 177.01 153 62 76 I 295 157 56 64 181.02 149 92 164 189 145 151 181.01175 72 160 195 123 54 70 166 183.01 68 78 162 125 40.01 183.02 121.01 135 50.02 48 GR CONCOURSE 173 143 185 44 BRUCKNER EXWY 152 131 127.01 121.02 52 CROSS BRONX EXWY DEEGAN EXWY 63 98 SHERIDAN EXWY 50.01 158 59.02 141 42 133 119 61 129.01 159 46 69 138 28 144 38 77 115.02 74 86 67 87 130 75 89 16 Sound View Park 110 I 295 65 71 20 24 90 79 85 84 132 118 73 BRUCKNER EXWY 43 83 51 2 37 41 35 31 117 4 39 23 93 33 25 27.02 27.01 19 1 Source: U.S. -

Annual Report 2017

Central Park Conservancy ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Table of Contents 2 Partnership 4 Letter from the Conservancy President 5 Letter from the Chairman of the Board of Trustees 6 Letter from the Mayor and the Parks Commissioner 7 Serving New York City’s Parks 8 Forever Green 12 Honoring Douglas Blonsky 16 Craftsmanship 18 Native Meadow Opens in the Dene Landscape 20 Electric Carts Provide Cleaner, Quieter Transportation 21 Modernizing the Toll Family Playground 22 Restoring the Ramble’s Watercourse 24 Enhancing and Diversifying the Ravine 26 Conservation of the Seventh Regiment Memorial 27 Updating the Southwest Corner 28 Stewardship 30 Operations by the Numbers 32 Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks 36 Community Programs 38 Volunteer Department 40 Friendship 46 Women’s Committee 48 The Greensward Circle 50 Financials 74 Supporters 114 Staff & Volunteers 124 Central Park Conservancy Mission, Guiding Principle, Core Values, and Credits Cover: Hallett Nature Sanctuary, Left: Angel Corbett 3 CENTRAL PARK CONSERVANCY Table of Contents 1 Partnership Central Park Conservancy From The Conservancy Chairman After 32 years of working in Central Park, Earlier this year Doug Blonsky announced that after 32 years, he would be stepping down as the it hasn’t been an easy decision to step Conservancy’s President and CEO. While his accomplishments in that time have been too numerous to count, down as President and CEO. But this it’s important to acknowledge the most significant of many highlights. important space has never been more First, under Doug’s leadership, Central Park is enjoying the single longest period of sustained health in its beautiful, better managed, or financially 160-year history. -

Long Island Tidal Wetlands Trends Analysis

LONG ISLAND TIDAL WETLANDS TRENDS ANALYSIS Prepared for the NEW ENGLAND INTERSTATE WATER POLLUTION CONTROL COMMISSION Prepared by August 2015 Long Island Tidal Wetlands Trends Analysis August 2015 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECOLOGICAL CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 6 FUNDING SOURCE AND PARTNERS ..................................................................................................................................... 6 TRENDS ANALYSIS .................................................................................................................................................. 7 METHODOLOGY AND DATA ................................................................................................................................... 9 OUTLINE OF TECHNICAL APPROACH ................................................................................................................................... 9 TECHNICAL OBJECTIVES -

Presented by Lizette Richardson and Richard Turk

National Park Service - Construction Program Management Lizette Richardson, Division Chief Richard Turk – Value Analysis Program Coordinator Partnerships and Caring for America’s Resources The National Park Service and Hurricane Sandy January, 2014 : Federal Utility Partnership Working Group (FUPWG) Construction Program Management Overview: n $50-80M Annual Line Item Construction Program n Division Programs n Value Analysis n Capital Asset Planning n Budget, Cost and Scope Oversight n Facility Planning Models n Policy Guidance n Design and Construction n Climate Change n Sustainability n Freeze-the-Footprint Hurricane Sandy Oct. 28, 2012: Category 1 storm - 1,000 miles in width n Hurricane Sandy affected 24 states, including the entire eastern seaboard from Florida to Maine and west across the Appalachian Mountains to Michigan and Wisconsin, with particularly severe damage in New Jersey and New York. (Wikipedia) n Damage US - $65 billion n Incident Command Response n Several national parks hit by Sandy n Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, Gateway, Fire Island, Asseteague, National Mall, etc. Hurricane Sandy The Response: n Disaster Relief Appropriations Act: (DOI $829.2 M) n National Park Service/Construction: $348 million ($329.8M post‐sequester) n Emergency Relief for Federally Owned Roads (ERFO) n Replacement-in-Kind – $20+M n Range of Project Types n Boardwalks, debris removal, roads, exhibits, restorations, bldgs. n Utility and HVAC n Limited Scale Projects Hurricane Sandy Recovery Projects Climate Change n Hurricane Sandy Task Force