Chapter 1 – Thusnelda Dawn, 14 AD, the Lippe River, December

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site

The Culture of Memory and the Role of Archaeology: A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site Laurel Fricker A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 18, 2017 Advised by Professor Julia Hell and Associate Professor Kerstin Barndt 1 Table of Contents Dedication and Thanks 4 Introduction 6 Chapter One 18 Chapter Two 48 Chapter Three 80 Conclusion 102 The Museum and Park Kalkriese Mission Statement 106 Works Cited 108 2 3 Dedication and Thanks To my professor and advisor, Dr. Julia Hell: Thank you for teaching CLCIV 350 Classical Topics: German Culture and the Memory of Ancient Rome in the 2016 winter semester at the University of Michigan. The readings and discussions in that course, especially Heinrich von Kleist’s Die Hermannsschlacht, inspired me to research more into the figure of Hermann/Arminius. Thank you for your guidance throughout this entire process, for always asking me to think deeper, for challenging me to consider the connections between Germany, Rome, and memory work and for assisting me in finding the connection I was searching for between Arminius and archaeology. To my professor, Dr. Kerstin Barndt: It is because of you that this project even exists. Thank you for encouraging me to write this thesis, for helping me to become a better writer, scholar, and researcher, and for aiding me in securing funding to travel to the Museum and Park Kalkriese. Without your support and guidance this project would never have been written. -

De 18E/19E Eeuwse Hoogovenvervuilinglaag in De Oude Ijsselafzettingen Bij Drempt

De 18e/19e eeuwse hoogovenvervuilinglaag in de Oude IJsselafzettingen bij Drempt Afstudeerscriptie LAD-80424 Student: F.R.P.M. Miedema Studentnr: 700411‐571‐080 Leerstoelgroep: Landdynamiek (LAD) Datum: November 2009 De 18e/19e eeuwse hoogovenvervuilingslaag in de Oude IJsselafzettingen bij Drempt Afstudeerscriptie LAD-80424 Examinator: Prof. dr. ir. A. Veldkamp Begeleiders: dr. J.M. Schoorl dr. Ir. M.W. van der Berg Student: ing. F.R.P.M. Miedema Studentnr: 700411‐571‐080 Leerstoelgroep: Landdynamiek (LAD) Datum: November 2009 De ijzerhut in ’t woud. Waaruit de koolstoom, dik en zwart, Het groen verkleurt van ’t hout. Daar spatten vonken, wijd en zijd, Daar zwoegt men, zweet en stookt altijd, En laat altijd de balgen blazen, Als moest men berg en rots verglazen. Schiller, 1797, Gang nach den Eisenhammer. Colofon Auteur: ing. F.R.P.M. Miedema Veldwerk: ing. F.R.P.M. Miedema Copyright: Wageningen Universiteit, leerstoelgroep Landdynamiek & F.R.P.M. Miedema Afbeelding omslag I: Reconstructie van de hoogoven met ijzergieterij in Ulft in de 18de eeuw door W. Gilles uit 1953 (WGIJ, 2007) Afbeelding omslag II: Foto van aangekraste bodemlagen in proefput 3 (28-07-2009). De proefput bevindt zich in een maïsperceel ten noorden van het Oude IJsselkanaal, op het perceel genaamd Stockhovens Land bij Drempt. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de Wageningen Universiteit, Leerstoelgroep Landdynamiek en F.R.P.M. Miedema. De 18de/19de eeuwse hoogovenvervuilinglaag in de Oude IJsselafzettingen bij Drempt Administratieve gegevens Onderzoekgegevens Datum opdracht WUR 13 mei 2008 Periode uitvoering veldwerk 6 juni 2008 tot 29 augustus 2008 Datum rapportage 23 november 2009 Uitvoerder ing. -

North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) / India

Page 1 of 13 Consulate General of India Frankfurt *** General and Bilateral Brief- North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) / India North Rhine-Westphalia, commonly shortened to NRW is the most populous state of Germany, with a population of approximately 18 million, and the fourth largest by area. It was formed in 1946 as a merger of the provinces of North Rhine and Westphalia, both formerly parts of Prussia, and the Free State of Lippe. Its capital is Düsseldorf; the largest city is Cologne. Four of Germany's ten largest cities—Cologne, Düsseldorf, Dortmund, and Essen— are located within the state, as well as the second largest metropolitan area on the European continent, Rhine-Ruhr. NRW is a very diverse state, with vibrant business centers, bustling cities and peaceful natural landscapes. The state is home to one of the strongest industrial regions in the world and offers one of the most vibrant cultural landscapes in Europe. Salient Features 1. Geography: The state covers an area of 34,083 km2 and shares borders with Belgium in the southwest and the Netherlands in the west and northwest. It has borders with the German states of Lower Saxony to the north and northeast, Rhineland-Palatinate to the south and Hesse to the southeast. Thinking of North Rhine-Westphalia also means thinking of the big rivers, of the grassland, the forests, the lakes that stretch between the Eifel hills and the Teutoburg Forest range. The most important rivers flowing at least partially through North Rhine-Westphalia include: the Rhine, the Ruhr, the Ems, the Lippe, and the Weser. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-10,982

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. White the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Anthropogenic Organic Contaminants in Sediments of the Lippe River, Germany Alexander Kronimus*, Jan Schwarzbauer, Larissa Dsikowitzky, Sabine Heim, Ralf Littke

ARTICLE IN PRESS Water Research 38 (2004) 3473–3484 Anthropogenic organic contaminants in sediments of the Lippe river, Germany Alexander Kronimus*, Jan Schwarzbauer, Larissa Dsikowitzky, Sabine Heim, Ralf Littke Institute of Geology and Geochemistry of Petroleum and Coal, RWTH Aachen University, Lochnerstrasse 4-20, D-52056 Aachen, Germany Received 13 August 2003; received in revised form 27 January2004; accepted 8 April 2004 Abstract Sediment samples of the Lippe river (Germany) taken between August 1999 and March 2001 were investigated by GC–MS-analyses. These analyses were performed as non-target-screening approaches in order to identify a wide range of anthropogenic organic contaminants. Unknown contaminants like 3,6-dichlorocarbazole and bis(4-octylphenyl) amine as well as anthropogenic molecular marker compounds were selected for quantification. The obtained qualitative and quantitative analytical results were interpreted in order to visualize the anthropogenic contamination of the Lippe river including spatial distribution, input effects and time dependent occurrence. Anthropogenic molecular markers derived from municipal sources like polycyclic musks, 4-oxoisophorone and methyltriclosan as well as from agricultural sources (hexachlorobenzene) were gathered. In addition molecular markers derived from effluents of three different industrial branches, e.g. halogenated organics, tetrachlorobenzyltoluenes and tetrabutyltin, were identified. While municipal and agricultural contaminations were ubiquitous and diffusive, industrial emission -

The Rhine River Crossings by Barry W

The Rhine River Crossings by Barry W. Fowle Each of the Allied army groups had made plans for the Rhine crossings. The emphasis of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) planning was in the north where the Canadians and British of Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery's 21st Army Group were to be the first across, followed by the Ninth United States Army, also under Montgomery. Once Montgomery crossed, the rest of the American armies to the south, 12th Army Group under General Omar N. Bradley and 6th Army Group under General Jacob L. Devers, would cross. On 7 March 1945, all that Slegburg changed. The 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, Combat Beuel Command B, 9th Armored Division, discovered that the Ludendorff bridge at 9th NFANR " Lannesdorf I0IV R Remagen in the First Army " Mehlem Rheinbach area was still standing and Oberbachem = : kum h RM Gelsd srn passed the word back to the q 0o~O kiVl 78th e\eaeo Combat Command B com- INP L)IV Derna Ahweile Llnz mander, Brigadier General SInzig e Neuenahi Helmershelm William M. Hoge, a former G1 Advance to the Rhine engineer officer. General 5 10 Mile Brohl Hoge ordered the immediate capture of the bridge, and Advance to the Rhine soldiers of the 27th became the first invaders since the Napoleonic era to set foot on German soil east of the Rhine. Crossings in other army areas followed before the month was. over leading to the rapid defeat of Hitler's armies in a few short weeks. The first engineers across the Ludendorff bridge were from Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion (AEB). -

Flüsse in NRW Wasserstraßen Durchs Land

Flüsse in NRW Wasserstraßen durchs Land Die Reihe "Alle Augen Auf..." lenkt dieses Mal den Fokus auf Flüsse in Nordrhein-Westfalen und beantwortet unter anderem folgende Fragen: Hat die Weser eigentlich eine Quelle? Woher kommt der Name "Ruhr"? Und ist der Rhein wirklich der längste Fluss in NRW? Menschen aus Nordrhein-Westfalen erzählen interessante, unterhaltende und spannende Geschichten über "ihren" Fluss. Lippe - 220 km Wer hat's gewusst? Nicht der Rhein, sondern die Lippe ist der längste Fluss in Nordrhein-Westfalen! Die Quelle entspringt in Bad Lippspringe, fließt dann auf 220 Kilometern durch NRW, bis sie sich bei Wesel mit dem Rhein vereint. Die Entstehung des Flusses umgibt eine Sage: Der nordische Gott Odin soll ein Auge geopfert haben, um dem trockenen Gebiet am Fuße des Teutoburger Waldes Leben zu schenken. Odins Auge - so wird die Quelle der Lippe deswegen auch genannt. Schon die Römer zog es an die Lippe und sie nutzten das Wasser, um ihre Güter zu transportieren. Und so ist die Römerroute entlang der Lippe eine weitere Besonderheit. Lange Zeit war die Wasserqualität der Lippe eher mäßig. In den 60er Jahren wurde daher künstlicher Sauerstoff in den Fluß gepumpt. Eine reichlich aufwändige Sache und nur von kurzem Erfolg. Langfristig heißt das Zauberwort "Renaturierung". Das bedeutet konkret: das Wasser zu säubern und den Fluss wieder mit seinen natürlichen Auen zu umgeben. Pate : Ulrich Detering arbeitet in Lippstadt als Wasserbauingenieur. Obwohl er gebürtig von der Weser kommt, ist er ein leidenschaftlicher Lippstädter und liebt das "Venedig Westfalens". Weitere Informationen : www.roemerlipperoute.de www.eglv.de/lippeverband/lippe Ruhr - 219 km Der 219,3 Kilometer lange Fluss ist namensgebend für eine ganze Region: das Ruhrgebiet. -

Germanicus Revisited-And Revised?

GERMANICUS REVISITED-AND REVISED? lo-Marie Claassen (University of Stellenbosch) This paper sets out to discuss a dramatic reworking of some chapters of Tacitus' Annales in the light of a recently discovered inscription containing the text of a decision of the Roman Senate, taken in the year A.D. 20. That Tacitus composed like a dramatist was fIrst mooted by Mendell in 1935, in an analysis of, among others, the fIrst eight books of Tacitus' Annales.1 This theory has been variously explored and fairly consistently shown to be tenable (Petersmann 1993, Cizek 1993, Billerbeck 1991, Fabbrini 1986, Wille 1983).2 Long before Mendell, Shakespeare's contemporary Ben Jonson, like the sculptor Michelangelo discovering 'the angel in the stone', exploited the dramatic potential of Ann. 4-8 in his fIve-act drama Sejanus, His Fall. As a play, it did not work for its contemporary audience, and it has seldom been performed. Its merit as a literary reworking of an interesting era has been variously extolled and criticized.3 Sejanus depicts the career of its eponymous anti-hero on a stage cluttered with characters. The drama entails a powerful analysis of the problem of corruption inherent in a despotic regime in a manner that touched the nerve of a despotic monarch (James I, who had shortly before the fIrst production of the play tried Sir Walter Raleigh for treason) to the Mendell (1935) discusses the Prologue to the Annales as dramatic (pp.9-10) and then concentrates on what he terms the "drama of Tiberius" in which Germanicus, Piso and Seianus in turn are used as foils to highlight the chief protagonist (pp.11-17) and the later "tragedy of Nero" (pp.18-28-see Muller 1994). -

Ijsselmeerzuflüsse Und Deren Einzugsgebiete in Westfalen

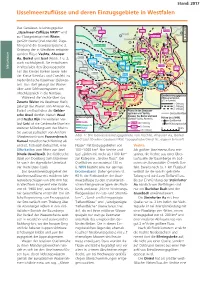

B3a_Layout 1 14.04.16 12:02 Seite 1 Stand: 2017 IJsselmeerzuflüsse und deren Einzugsgebiete in Westfalen Das Gewässer-Teileinzugsgebiet 30 Em Rijssen s Regge Dinkel Vechte „IJsselmeer-Zuflüsse NRW” wird Hengelo T Rheine Eileringsbeke h zur Flussgebietseinheit Rhein Goor Gronau ie Enschede (W.) G 39 b o e 35 o rg gezählt (www.ijssel.nrw.de). Zuge- rb Ochtrup a 47 h c h c Wettr. hörig sind die Gewässersysteme 2. Buurserbeek H ba r or n Haaksbergen l e F b Dinkel e Gaux- Ordnung der in Westfalen entsprin- c A k bach Lochem e lt 28 Stein- e genden Flüsse Vechte, Ahauser Berkel 39 n Zodde- 60 furt b Baakse ach e Aa, Berkel und Issel (Abbn. 1 u. 2, bach Alsttter Aa erb r Groenlose Le g Ahaus Heek e auch nachfolgend). Sie entwässern Slinge Eibergen Huning- r bach Flrb. Schpp. H Groenlo 31 Vechte Berg in Westfalen den überwiegenden l- Ahauser Aa Steinf. h Naturraum Veengoot e bach 65 Aa n Vreden 55 61 Mhlenba Teil des Kreises Borken sowie Teile ch Burl. B. Baakse Winters- Berkel Legden 110 110 der Kreise Steinfurt und Coesfeld ins wijk Stadtlohn Dinkel 95 88 98 Welling- M Baum- 135 A ns niederländische IJsselmeer (Süßwas- bach a te Fels- rs Boven-Slinge Billerbeck ch AaltenAalten bach Coesfd. berge . ser). Von dort gelangt das Wasser 55 80 Honig- 125 beek 25 Schlinge Gescher IJssel s- bach S er R te über zwei Schleusen sys teme am iz o g v e K r 15 K up Ber e ch n Velen 66 er r Aastrang a B s H Abschlussdeich in die Nordsee. -

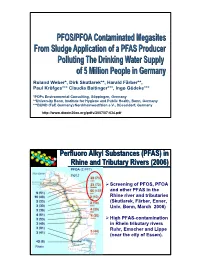

Pdf 22.01.2016 86 Weberr PFOS-PFAS Roland Weber/Dirk

Roland Weber*, Dirk Skutlarek**, Harald Färber**, Paul Kröfges*** Claudia Baitinger***, Ingo Gödeke*** *POPs Environmental Consulting, Göppingen, Germany **University Bonn, Institute for Hygiene and Public Health, Bonn, Germany ***BUND (FoE Germany) Nordrheinwestfalen e.V., Düsseldorf, Germany http://www.dioxin20xx.org/pdfs/2007/07-634.pdf ¾ Screening of PFOS, PFOA and other PFAS in the Rhine river and tributaries (Skutlarek, Färber, Exner, Univ. Bonn, March 2006) ¾ High PFAS-contamination in Rhein tributary rivers Ruhr, Emscher and Lippe (near the city of Essen). 1 Tracing the PFAS- contamination in the Ruhr back to Möhne river and tributary creeks. Extreme high concentrations of PFOA and other PFAS in the Moehne river and tributaries. Skutlarek, Exner, Färber, Environ Sci Pollut Res 13 (5) 299 – 307 (2006) 2 Contam Sites Ruhrwasser (Presentation 12/2006) Lake Moehne (drinking water reservoir for ca. 5 million people) with a volume of 134.5 million m3, was contaminated with ΣPFAS of 822 ng/l. Calculated concentration in the lake: 110.5 kg PFAS. ¾After July 2006: use of two other dams with non contaminated water to dilute high concentrations of theMoehnedam to adjustthe concentration in the Ruhr to below 300 ng PFAS/l (just meeting the preliminarily established drinking water limits). ¾ The Moehne Reservoir released slowly the approx. 110 kg PFAS into the Ruhr and via Rhein finally into the North Sea contaminating on their way drinking water and fish. 3 ¾ The PFOS/PFOA contaminated agricultural fields resulted from mismanagement of PFAS contaminated sludge of a PFAS producer which was imported via a Dutch trader to a German company (in accordance with EU hazardous Waste Shipment Regulation (EEC 259/93).