Other Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Common Mussurana, Clelia Clelia, Is a Widespread Colubrid Found Throughout Much of Central and South America

The Common Mussurana, Clelia clelia, is a widespread colubrid found throughout much of Central and South America. One unusual feature of this snake is its ontogenetic color change, as juveniles (above; KU 181136) display markedly different coloration from adults, which are uniform bluish black. In the following study we quantitatively measured the coloration patterns of 105 juvenile museum specimens of this species from many localities throughout its range, and found strong geographic patterns in the shape and size of the head bands. To our knowledge, this information on color pattern variation has not been reported. ' © Luke Welton 111 Arquilla and Lehtinen Head band shape in juveniles of Clelia clelia www.mesoamericanherpetology.com www.eaglemountainpublishing.com Geographic variation in head band shape in juveniles of Clelia clelia (Colubridae) APRIL M. ARQUILLA AND RICHARD M. LEHTINEN Department of Biology, The College of Wooster, 554 E. University St., Wooster, Ohio 44691, United States. E-mail: [email protected] (RML, Corresponding author) ABSTRACT: Color variability influences many aspects of organismal function, such as camouflage, mating displays, and thermoregulation. Coloration patterns frequently vary geographically and sometimes among life stages of the same species. One widely distributed snake species that shows ontogenetic color change is Clelia clelia (Colubridae). No quantitative studies, however, have assessed coloration patterns in this species. To fill this gap and to assess color pattern variation within this species, we measured the lengths of the head and neck bands of 105 specimens of C. clelia from across much of its geographic range. We found that the head band shape and length of specimens from Amazonia and the Atlantic Forest were significantly different compared to those from Central America and the Pacific or Caribbean coasts of South America, and that they stem from a difference in the shape of the first black collar on the snout and the anterior portion of the head. -

Herpetological Information Service No

Type Descriptions and Type Publications OF HoBART M. Smith, 1933 through June 1999 Ernest A. Liner Houma, Louisiana smithsonian herpetological information service no. 127 2000 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. Introduction Hobart M. Smith is one of herpetology's most prolific autiiors. As of 30 June 1999, he authored or co-authored 1367 publications covering a range of scholarly and popular papers dealing with such diverse subjects as taxonomy, life history, geographical distribution, checklists, nomenclatural problems, bibliographies, herpetological coins, anatomy, comparative anatomy textbooks, pet books, book reviews, abstracts, encyclopedia entries, prefaces and forwords as well as updating volumes being repnnted. The checklists of the herpetofauna of Mexico authored with Dr. Edward H. Taylor are legendary as is the Synopsis of the Herpetofalhva of Mexico coauthored with his late wife, Rozella B. -

CAT Vertebradosgt CDC CECON USAC 2019

Catálogo de Autoridades Taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala CDC-CECON-USAC 2019 Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Este documento fue elaborado por el Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) del Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala, 2019 Textos y edición: Manolo J. García. Zoólogo CDC Primera edición, 2019 Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala ISBN: 978-9929-570-19-1 Cita sugerida: Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon]. (2019). Catálogo de autoridades taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala (Documento técnico). Guatemala: Centro de Datos para la Conservación [CDC], Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon], Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala [Usac]. Índice 1. Presentación ............................................................................................ 4 2. Directrices generales para uso del CAT .............................................. 5 2.1 El grupo objetivo ..................................................................... 5 2.2 Categorías taxonómicas ......................................................... 5 2.3 Nombre de autoridades .......................................................... 5 2.4 Estatus taxonómico -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

The Role of the Matrix-Edge Dynamics of Amphibian Conservation in Tropical Montane Fragmented Landscapes

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 82: 679-687, 2011 The role of the matrix-edge dynamics of amphibian conservation in tropical montane fragmented landscapes La dinámica del borde-matriz en bosques mesófilos de montaña fragmentados y su papel en la conservación de los anfibios Georgina Santos-Barrera1 and J. Nicolás Urbina-Cardona1,2* 1Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autônoma de México. 70-399, 04510 México D.F., México. 2 Departamento de Ecología y Territorio. Facultad de Estudios Ambientales y Rurales, Universidad Javeriana. Transv. 4, núm. 42-00. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract . Edge effects play a key role in forest dynamics in which the context of the anthropogenic matrix has a great influence on fragment connectivity and function. The study of the interaction between edge and matrix effects in nature is essential to understand and promote the colonization of some functional groups in managed ecosystems. We studied the dynamics of 7 species of frogs and salamanders occurring in 8 ecotones of tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF) which interact with adjacent managed areas of coffee and corn plantations in Guerrero, southern Mexico. A survey effort of 196 man/hours along 72 transects detected 58 individuals of 7 amphibian species and 12 environmental and structural variables were measured. The diversity and abundance of amphibians in the forest mostly depended on the matrix context adjacent to the forest patches. The forest interior provided higher relative humidity, leaf litter cover, and canopy cover that determined the presence of some amphibian species. The use of shaded coffee plantations was preferred by the amphibians over the corn plots possibly due to the maintenance of native forest arboreal elements, low management rate and less intensity of disturbance in the coffee plantations than in the corn plots. -

Stiiemtific PNSTHTUTHQNS in LATIN AMERICA the BUTANTAN Institutel

StiIEMTIFIC PNSTHTUTHQNS IN LATIN AMERICA THE BUTANTAN INSTITUTEl Director: Dr. Jayme Cavalcanti Xão Paulo, Brazil The ‘%utantan Institute of Serum-Therapy,” situated in the middle of a large park on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, was founded in 1899 by the Government of the State primarily for the purpose of preparing plague vaccine and serum. Dr. Vital Brazil, the first Director of the Institute, resumed there the studies on snake poisons which he had begun in 1895 on his return from France, and his work and that of his colleagues soon caused the Institute to become world-famous for its work in that field. Dr. Brazil was one of the first workers to observe the specificity of snake venom, that is, that different species of snakes have different venoms and that, therefore, different sera must be made for treating their bites. His work on snake poisons included zoological studies of the various species of snakes in the country, with their geographic distribution, biology, common names, types of venom, etc.; the prepara- tion of sera from various types of venom; the teaching of preventive measures, including the method of capturing snakes and sending them ’ to the specialized centers; establishment of a system of exchange of live snakes for ampules of serum between the farmers and the Insti- tute; the introduction into the death certificate of an entry for the recording of snake-bite as a cause of death, and the compiling of sta- tistics of bites, treatment used, and results. Dr. Brazil was followed in the directioqof the Institute, in 1919, by Dr. -

For Review Only

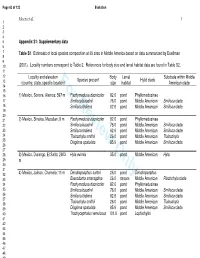

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Pseudoeurycea Naucampatepetl. the Cofre De Perote Salamander Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico. This

Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl. The Cofre de Perote salamander is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This relatively large salamander (reported to attain a total length of 150 mm) is recorded only from, “a narrow ridge extending east from Cofre de Perote and terminating [on] a small peak (Cerro Volcancillo) at the type locality,” in central Veracruz, at elevations from 2,500 to 3,000 m (Amphibian Species of the World website). Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl has been assigned to the P. bellii complex of the P. bellii group (Raffaëlli 2007) and is considered most closely related to P. gigantea, a species endemic to the La specimens and has not been seen for 20 years, despite thorough surveys in 2003 and 2004 (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org), and thus it might be extinct. The habitat at the type locality (pine-oak forest with abundant bunch grass) lies within Lower Montane Wet Forest (Wilson and Johnson 2010; IUCN Red List website [accessed 21 April 2013]). The known specimens were “found beneath the surface of roadside banks” (www.edgeofexistence.org) along the road to Las Lajas Microwave Station, 15 kilometers (by road) south of Highway 140 from Las Vigas, Veracruz (Amphibian Species of the World website). This species is terrestrial and presumed to reproduce by direct development. Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl is placed as number 89 in the top 100 Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered amphib- ians (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org). We calculated this animal’s EVS as 17, which is in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its IUCN status has been assessed as Critically Endangered. -

Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names

Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus-group names. Part V Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart Evenhuis, Neal L.; Pape, Thomas; Pont, Adrian C. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Evenhuis, N. L., Pape, T., & Pont, A. C. (2016). Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus- group names. Part V: Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart. Magnolia Press. Zootaxa Vol. 4172 No. 1 https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Zootaxa 4172 (1): 001–211 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:22128906-32FA-4A80-85D6-10F114E81A7B ZOOTAXA 4172 Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names. Part V: Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart NEAL L. EVENHUIS1, THOMAS PAPE2 & ADRIAN C. PONT3 1 J. Linsley Gressitt Center for Entomological Research, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817-2704, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universitetsparken 15, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] 3Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PW, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by D. Whitmore: 15 Aug. 2016; published: 30 Sept. 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 NEAL L. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Crocodylus Moreletii

ANFIBIOS Y REPTILES: DIVERSIDAD E HISTORIA NATURAL VOLUMEN 03 NÚMERO 02 NOVIEMBRE 2020 ISSN: 2594-2158 Es un publicación de la CONSEJO DIRECTIVO 2019-2021 COMITÉ EDITORIAL Presidente Editor-en-Jefe Dr. Hibraim Adán Pérez Mendoza Dra. Leticia M. Ochoa Ochoa Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Senior Editors Vicepresidente Dr. Marcio Martins (Artigos em português) Dr. Óscar A. Flores Villela Dr. Sean M. Rovito (English papers) Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Editores asociados Secretario Dr. Uri Omar García Vázquez Dra. Ana Bertha Gatica Colima Dr. Armando H. Escobedo-Galván Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez Dr. Oscar A. Flores Villela Dra. Irene Goyenechea Mayer Goyenechea Tesorero Dr. Rafael Lara Rezéndiz Dra. Anny Peralta García Dr. Norberto Martínez Méndez Conservación de Fauna del Noroeste Dra. Nancy R. Mejía Domínguez Dr. Jorge E. Morales Mavil Vocal Norte Dr. Hibraim A. Pérez Mendoza Dr. Juan Miguel Borja Jiménez Dr. Jacobo Reyes Velasco Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango Dr. César A. Ríos Muñoz Dr. Marco A. Suárez Atilano Vocal Centro Dra. Ireri Suazo Ortuño M. en C. Ricardo Figueroa Huitrón Dr. Julián Velasco Vinasco Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México M. en C. Marco Antonio López Luna Dr. Adrián García Rodríguez Vocal Sur M. en C. Marco Antonio López Luna Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco English style corrector PhD candidate Brett Butler Diseño editorial Lic. Andrea Vargas Fernández M. en A. Rafael de Villa Magallón http://herpetologia.fciencias.unam.mx/index.php/revista NOTAS CIENTÍFICAS SKIN TEXTURE CHANGE IN DIASPORUS HYLAEFORMIS (ANURA: ELEUTHERODACTYLIDAE) ..................... 95 CONTENIDO Juan G. Abarca-Alvarado NOTES OF DIET IN HIGHLAND SNAKES RHADINAEA EDITORIAL CALLIGASTER AND RHADINELLA GODMANI (SQUAMATA:DIPSADIDAE) FROM COSTA RICA .....