2011 Elliott Protecting Cave Life 2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-Dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus Spp

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2005 The aN tural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia Michael Steven Osbourn Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Osbourn, Michael Steven, "The aN tural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia" (2005). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 735. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia. Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Biological Sciences By Michael Steven Osbourn Thomas K. Pauley, Committee Chairperson Daniel K. Evans, PhD Thomas G. Jones, PhD Marshall University May 2005 Abstract The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia. Michael S. Osbourn There are over 4000 documented caves in West Virginia, potentially providing refuge and habitat for a diversity of amphibians and reptiles. Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus porphyriticus, are among the most frequently encountered amphibians in caves. Surveys of 25 caves provided expanded distribution records and insight into ecology and diet of G. -

<I>Salamandra Salamandra</I>

International Journal of Speleology 46 (3) 321-329 Tampa, FL (USA) September 2017 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Subterranean systems provide a suitable overwintering habitat for Salamandra salamandra Monika Balogová1*, Dušan Jelić2, Michaela Kyselová1, and Marcel Uhrin1,3 1Institute of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, P. J. Šafárik University, Šrobárova 2, 041 54 Košice, Slovakia 2Croatian Institute for Biodiversity, Lipovac I., br. 7, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3Department of Forest Protection and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Kamýcká 1176, 165 21 Praha, Czech Republic Abstract: The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) has been repeatedly noted to occur in natural and artificial subterranean systems. Despite the obvious connection of this species with underground shelters, their level of dependence and importance to the species is still not fully understood. In this study, we carried out long-term monitoring based on the capture-mark- recapture method in two wintering populations aggregated in extensive underground habitats. Using the POPAN model we found the population size in a natural shelter to be more than twice that of an artificial underground shelter. Survival and recapture probabilities calculated using the Cormack-Jolly-Seber model were very constant over time, with higher survival values in males than in females and juveniles, though in terms of recapture probability, the opposite situation was recorded. In addition, survival probability obtained from Cormack-Jolly-Seber model was higher than survival from POPAN model. The observed bigger population size and the lower recapture rate in the natural cave was probably a reflection of habitat complexity. -

<I>Geomyces Destructans</I> Sp. Nov. Associated with Bat White-Nose

MYCOTAXON Volume 108, pp. 147–154 April–June 2009 Geomyces destructans sp. nov. associated with bat white-nose syndrome A. Gargas1, M.T. Trest2, M. Christensen3 T.J. Volk4 & D.S. Blehert5* [email protected] Symbiology LLC Middleton, WI 53562 USA [email protected] Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin — Madison Birge Hall, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, WI 53706 USA [email protected] 1713 Frisch Road, Madison, WI 53711 USA [email protected] Department of Biology, University of Wisconsin — La Crosse 3024 Crowley Hall, La Crosse, WI 54601 USA [email protected] U.S. Geological Survey — National Wildlife Health Center 6006 Schroeder Road, Madison, WI 53711 USA Abstract — We describe and illustrate the new species Geomyces destructans. Bats infected with this fungus present with powdery conidia and hyphae on their muzzles, wing membranes, and/or pinnae, leading to description of the accompanying disease as white-nose syndrome, a cause of widespread mortality among hibernating bats in the northeastern US. Based on rRNA gene sequence (ITS and SSU) characters the fungus is placed in the genus Geomyces, yet its distinctive asymmetrically curved conidia are unlike those of any described Geomyces species. Key words — Ascomycota, Helotiales, Pseudogymnoascus, psychrophilic, systematics Introduction Bat white-nose syndrome (WNS) was first documented in a photograph taken at Howes Cave, 52 km west of Albany, NY USA during winter, 2006 (Blehert et al. 2009). As of March 2009, WNS has been confirmed by gross and histologic examination of bats at caves and mines in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Vermont, West Virginia, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. -

25 Chrysosporium

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade do Minho: RepositoriUM 25 Chrysosporium Dongyou Liu and R.R.M. Paterson contents 25.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 197 25.1.1 Classification and Morphology ............................................................................................................................ 197 25.1.2 Clinical Features .................................................................................................................................................. 198 25.1.3 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................................................. 199 25.2 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................................... 199 25.2.1 Sample Preparation .............................................................................................................................................. 199 25.2.2 Detection Procedures ........................................................................................................................................... 199 25.3 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................................................200 -

Biosafety Measures for Working with Pseudogymnoascus Destructans in the Laboratory and Use Or Storage of Potentially Contaminated Materials

Biosafety Measures for Working with Pseudogymnoascus destructans in the Laboratory and Use or Storage of Potentially Contaminated Materials The emergent disease of bats, white-nose syndrome (WNS), has caused one of the most precipitous declines documented among North American wildlife. This disease is caused by the recently described fungal pathogen Pseudogymnoascus (formerly Geomyces) destructans. Because of the grave threat this fungus presents to populations of hibernating bats, precautions must be taken when working with P. destructans in the laboratory to prevent accidental release of the fungus into the environment. The following guidelines apply to all members of the WNS Diagnostic Laboratory Network. Other laboratories that work with P. destructans or that maintain specimens that may harbor viable fungus may use these guidelines to develop appropriate institutional standards for preventing accidental release of a Biosafety Level-2 (BSL-2) fungal pathogen of animals. Based upon biological risk assessment, work in the laboratory with viable P. destructans should be restricted to BSL-2 or higher. Adherence to this guidance will ensure that in accordance with the manual Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5th Edition, appropriate procedures, mechanical controls, and containment equipment are in place to facilitate biosecure work with the fungus and to prevent accidental release. Use of a biosafety cabinet. Fungi such as P. destructans readily produce aerosolizeable, environmentally resistant, and long-lived spores (reproductive structures). Therefore, all manipulations of potentially viable P. destructans (fungal cultures, carcasses, unfixed tissue samples, wing swabs, environmental samples, fungal tape lifts) in the laboratory should be restricted to a certified Class I or Class II biosafety cabinet. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

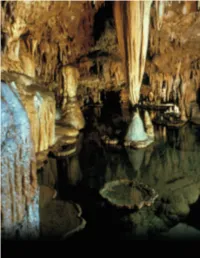

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

25 Chrysosporium

25 Chrysosporium Dongyou Liu and R.R.M. Paterson contents 25.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 197 25.1.1 Classification and Morphology ............................................................................................................................ 197 25.1.2 Clinical Features .................................................................................................................................................. 198 25.1.3 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................................................. 199 25.2 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................................... 199 25.2.1 Sample Preparation .............................................................................................................................................. 199 25.2.2 Detection Procedures ........................................................................................................................................... 199 25.3 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................................................200 References .................................................................................................................................................................................200 -

Real-Time PCR for Geomyces Destructans Bat White-Nose Syndrome

In Press at Mycologia, preliminary version published on September 6, 2012 as doi:10.3852/12-242 Short title: Real-time PCR for Geomyces destructans Bat white-nose syndrome: a real-time TaqMan polymerase chain reaction test targeting the intergenic spacer region of Geomyces destructans Laura K. Muller US Geological Survey. National Wildlife Health Center, 6006 Schroeder Road, Madison, Wisconsin 53711 Jeffrey M. Lorch Molecular and Environmental Toxicology Center, University of Wisconsin at Madison, Medical Sciences Center, 1300 University Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Daniel L. Lindner1 US Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Center for Forest Mycology Research, One Gifford Pinchot Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53726 Michael O’Connor1 Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, 445 Easterday Lane, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Andrea Gargas Symbiology LLC, Middleton, Wisconsin 53562 USA David S. Blehert2 US Geological Survey, National Wildlife Health Center, 6006 Schroeder Road, Madison, Wisconsin 53711 Copyright 2012 by The Mycological Society of America. Abstract: The fungus Geomyces destructans is the causative agent of white-nose syndrome (WNS), a disease that has killed millions of North American hibernating bats. We describe a real-time TaqMan PCR test that detects DNA from G. destructans by targeting a portion of the multicopy intergenic spacer region of the rRNA gene complex. The test is highly sensitive, consistently detecting as little as 3.3 fg genomic DNA from G. destructans. The real-time PCR test specifically amplified genomic DNA from G. destructans but did not amplify target sequence from 54 closely related fungal isolates (including 43 Geomyces spp. isolates) associated with bats. The test was qualified further by analyzing DNA extracted from 91 bat wing skin samples, and PCR results matched histopathology findings. -

Curriculum Vitae (PDF)

CURRICULUM VITAE Steven J. Taylor April 2020 Colorado Springs, Colorado 80903 [email protected] Cell: 217-714-2871 EDUCATION: Ph.D. in Zoology May 1996. Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois; Dr. J. E. McPherson, Chair. M.S. in Biology August 1987. Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas; Dr. Merrill H. Sweet, Chair. B.A. with Distinction in Biology 1983. Hendrix College, Conway, Arkansas. PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS: • Associate Research Professor, Colorado College (Fall 2017 – April 2020) • Research Associate, Zoology Department, Denver Museum of Nature & Science (January 1, 2018 – December 31, 2020) • Research Affiliate, Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (16 February 2018 – present) • Department of Entomology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2005 – present) • Department of Animal Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (March 2016 – July 2017) • Program in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology (PEEC), School of Integrative Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (December 2011 – July 2017) • Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (2005 – July 2017) • Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign (2004 – 2007) PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS: Swanson, D.R., S.W. Heads, S.J. Taylor, and Y. Wang. A new remarkably preserved fossil assassin bug (Insecta: Heteroptera: Reduviidae) from the Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado. Palaeontology or Papers in Palaeontology (Submitted 13 February 2020) Cable, A.B., J.M. O’Keefe, J.L. Deppe, T.C. Hohoff, S.J. Taylor, M.A. Davis. Habitat suitability and connectivity modeling reveal priority areas for Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) conservation in a complex habitat mosaic. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Beneficial Forest Mgmt. Practices for WNS Affected Bats

Beneficial Forest Management Practices for WNS-affected Bats Voluntary Guidance for Land Managers and Woodland Owners in the Eastern United States May 2018 Please cite this document as: Johnson, C.M. and R.A. King, eds. 2018. Beneficial Forest Management Practices for WNS-affected Bats: Voluntary Guidance for Land Managers and Woodland Owners in the Eastern United States. A product of the White-nose Syndrome Conservation and Recovery Working Group established by the White-nose Syndrome National Plan (www.whitenosesyndrome.org). 39 pp. BACKGROUND This document was prepared and reviewed by a diverse group of volunteers from universities, federal and state agencies, and non-governmental organizations functioning as a subgroup of the Conservation and Recovery Working Group (CRWG), which was established via A National Plan for Assisting States, Federal Agencies, and Tribes in Managing White-Nose Syndrome in Bats (a.k.a. the “National Plan”; USFWS 2011a (available at www.whitenosesyndrome.org). The need for beneficial forest management practices (BFMPs) for bats and forest management was identified by the CRWG and conceptualized during the 2013 White-Nose Syndrome Workshop held in Boise, Idaho. This document contains detailed information, including a glossary of bat and forest management- related terms (defined terms are underlined and are linked to the glossary) and citations for pertinent scientific literature to help land managers and others interested in gaining a deeper understanding of the underlying science and related issues that were considered when developing the BFMPs. An abbreviated and condensed version of these BFMPs is being planned and will be available as a user-friendly brochure at https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org when completed. -

H:\Ken\Salamander\SALAMANDERS W-Cover & Toc.Wpd

Table of Contents I. Introduction ........................................................1 II. Species Accounts ....................................................1 A. Cave Salamander, Eurycea lucifuga Rafinesque ......................1 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................1 2. Historical and Current Distribution ...........................1 3. Species Associations .....................................2 4. Population Sizes and Abundance ............................2 5. Reproduction ...........................................3 6. Food and Feeding Requirements ............................3 B. Many Ribbed Salamander, Eurycea multiplicata geiseogaster ...........3 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................3 2. Life History and Ecological Information ........................3 C. Grotto Salamander, Typlotriton spealaeus Stejneger ...................4 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................4 2. Life History Information and Habitats .........................4 D. Long-tailed Salamander Eurycea longicauda melanopleura Cope ........5 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................5 2. Historical and Current Distribution ...........................5 3. Life History Information ...................................6 III. Ownership of Species Habitats ..........................................6 IV. Potential Threats to Species or Their Habitats ...............................6 V. Protective Laws .....................................................7 A. Federal .....................................................7