The Cinematic Wink: Representations of Winking in Screen Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

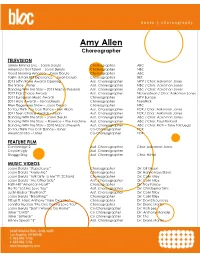

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

Marble Hornets, the Slender Man, and The

DIGITAL FOLKLORE: MARBLE HORNETS, THE SLENDER MAN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF FOLK HORROR IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Dana Keller B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Dana Keller, 2013 Abstract In June 2009 a group of forum-goers on the popular culture website, Something Awful, created a monster called the Slender Man. Inhumanly tall, pale, black-clad, and with the power to control minds, the Slender Man references many classic, canonical horror monsters while simultaneously expressing an acute anxiety about the contemporary digital context that birthed him. This anxiety is apparent in the collective legends that have risen around the Slender Man since 2009, but it figures particularly strongly in the Web series Marble Hornets (Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage June 2009 - ). This thesis examines Marble Hornets as an example of an emerging trend in digital, online cinema that it defines as “folk horror”: a subgenre of horror that is produced by online communities of everyday people— or folk—as opposed to professional crews working within the film industry. Works of folk horror address the questions and anxieties of our current, digital age by reflecting the changing roles and behaviours of the everyday person, who is becoming increasingly involved with the products of popular culture. After providing a context for understanding folk horror, this thesis analyzes Marble Hornets through the lens of folkloric narrative structures such as legends and folktales, and vernacular modes of filmmaking such as cinéma direct and found footage horror. -

JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE and BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release February 1994 JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994 A film retrospective of the legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau, spanning her remarkable forty-five year career, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on February 25, 1994. JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND traces the actress's steady rise from the French cinema of the 1950s and international renown as muse and icon of the New Wave movement to the present. On view through March 18, the exhibition shows Moreau to be one of the few performing artists who both epitomize and transcend their eras by the originality of their work. The retrospective comprises thirty films, including three that Moreau directed. Two films in the series are United States premieres: The Old Woman Mho Wades in the Sea (1991, Laurent Heynemann), and her most recent film, A Foreign Field (1993, Charles Sturridge), in which Moreau stars with Lauren Bacall and Alec Guinness. Other highlights include The Queen Margot (1953, Jean Dreville), which has not been shown in the United States since its original release; the uncut version of Eva (1962, Joseph Losey); the rarely seen Mata Hari, Agent H 21 (1964, Jean-Louis Richard), and Joanna Francesa (1973, Carlos Diegues). Alternately playful, seductive, or somber, Moreau brought something truly modern to the screen -- a compelling but ultimately elusive persona. After perfecting her craft as a principal member of the Comedie Frangaise and the Theatre National Populaire, she appeared in such films as Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1957) and The Lovers (1958), the latter of which she created a scandal with her portrayal of an adultress. -

Al Pacino Receives Bfi Fellowship

AL PACINO RECEIVES BFI FELLOWSHIP LONDON – 22:30, Wednesday 24 September 2014: Leading lights from the worlds of film, theatre and television gathered at the Corinthia Hotel London this evening to see legendary actor and director, Al Pacino receive a BFI Fellowship – the highest accolade the UK’s lead organisation for film can award. One of the world’s most popular and iconic stars of stage and screen, Pacino receives a BFI Fellowship in recognition of his outstanding achievement in film. The presentation was made this evening during an exclusive dinner hosted by BFI Chair, Greg Dyke and BFI CEO, Amanda Nevill, sponsored by Corinthia Hotel London and supported by Moët & Chandon, the official champagne partner of the Al Pacino BFI Fellowship Award Dinner. Speaking during the presentation, Al Pacino said: “This is such a great honour... the BFI is a wonderful thing, how it keeps films alive… it’s an honour to be here and receive this. I’m overwhelmed – people I’ve adored have received this award. I appreciate this so much, thank you.” BFI Chair, Greg Dyke said: “A true icon, Al Pacino is one of the greatest actors the world has ever seen, and a visionary director of stage and screen. His extraordinary body of work has made him one of the most recognisable and best-loved stars of the big screen, whose films enthral and delight audiences across the globe. We are thrilled to honour such a legend of cinema, and we thank the Corinthia Hotel London and Moët & Chandon for supporting this very special occasion.” Alongside BFI Chair Greg Dyke and BFI CEO Amanda Nevill, the Corinthia’s magnificent Ballroom was packed with talent from the worlds of film, theatre and television for Al Pacino’s BFI Fellowship presentation. -

Probst Resume

CHRISTOPHER PROBST Director of Photography FEATURES BEYOND SKYLINE Liam O’Donnell Hydraulx HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS Tommy Wirkola Paramount / Gary Sanchez Prods. (Add’l Photography) FIRE WITH FIRE David Barrett Lionsgate / Emmett/Furla Films DETENTION Joseph Kahn Richard Weager / Detention Films Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2011) SKY CAPTAIN & THE WORLD Kerry Conran Paramount / Brooklyn nd OF TOMORROW (2 Unit) TELEVISION BOOMTOWN (2nd Unit) Jon Avnet / Various NBC / Dreamworks DIRECTORS & COMMERCIALS CYRIL GUYOT Mercedes MARK PALANSKY Target TWIN HP STUART PARR Coors Light GRADY HALL Target ALEX AND LEANNE Mercedes JULIEN ROCHER K1664 PHIL BROWN Coors Light JAKE BANKS Toyota JOSEPH KAHN Malibu Rum, Old Navy, LG, Smart Car, Naturemade, Gilette, Bell, Mentos, Clearasil, Blackberry, Solon Energy, BMW, Sears, Bacardi, Mazda, Saab, Citroen, HP, Fox Sports/Nascar, JC Penney, Travelers Insurance, Budweiser Select, AKB48, UFC, Orangina, Johnny Walker, RICH LEE Subaru, Disney Hong Kong, La Gazzetto Dello Sport, Eni Energy, Beats, Special K, Carls Jr., Hyundai, Nissan NIMA NOURIZADEH Adidas BEN MOR Cisco EMNET Lincoln LOGAN Twizzlers, Directv, Exxon MATT OGENS Farmer John WOODS Century 21 SHILO Sports Authority JOHN PARK Kia HIRO MURAI Scion ERIK BUTH Asgrow, Verizon, Kyocera, 1st National Bank, Pringles, Russell Athletics TOM KOH Fox Sports DAVE MEYERS Ciroc Vodka, Lexus MARCELLO PETRELLA Honda, Taylor Made, Bud Light JONG WON KIM Hyundai MATT PIEDMONT Microsoft BOB RICE Prestone, Vegas.Com, Phillips DAN RUSH TBS Promo “My Boys”, TNT Promo TYLER GRECO NFL Terrell Owens Promo ROB HOOVER Direct TV “Mega March Madness” KURT SPENCER Fearnet Promo, TNT Promo ROB MELTZER TLC “Summer” Campaign, Bravo Promo “Launch My Line” DIRECTORS & MUSIC VIDEOS JOSEPH KAHN Lady Gaga, Eminem “Space Bound”, “Love the Way You Lie”, Muse “Knights of Cydonia”, Nicole Scherzinger “Poison”, Britney Spears “Womanizer”, Pussycat Dolls “I Hate This Part”, “When I Grow Up”, Janet Jackson “So Excited” 50 Cent Feat. -

Sherlock Holmes

sunday monday tuesday wednesday thursday friday saturday KIDS MATINEE Sun 1:00! FEB 23 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 24 & 25 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 26 & 27 (3:00 & 7:00 & 9:15) KIDS MATINEE Sat 1:00! UP CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF MEATBALLS THE HURT LOCKER THE DAMNED PRECIOUS FEB 21 (3:00 & 7:00) Director: Kathryn Bigelow (USA, 2009, 131 mins; DVD, 14A) Based on the novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire FEB 22 (7:00 only) Cast: Jeremy Renner Anthony Mackie Brian Geraghty Ralph UNITED Director: Lee Daniels Fiennes Guy Pearce . (USA, 2009, 111 min; 14A) THE IMAGINARIUM OF “AN INSTANT CLASSIC!” –Wall Street Journal Director: Tom Hooper (UK, 2009, 98 min; PG) Cast: Michael Sheen, Cast: Gabourey Sidibe, Paula Patton, Mo’Nique, Mariah Timothy Spall, Colm Meaney, Jim Broadbent, Stephen Graham, Carey, Sherri Shepherd, and Lenny Kravitz “ENTERS THE PANTEHON and Peter McDonald DOCTOR PARNASSUS OF GREAT AMERICAN WAR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS MO’NIQUE FILMS!” –San Francisco “ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE GENRE!” –Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild Director: Terry Gilliam (UK/Canada/France, 2009, 123 min; PG) –San Francisco Chronicle Cast: Heath Ledger, Christopher Plummer, Tom Waits, Chronicle ####! The One of the most telling moments of this shockingly beautiful Lily Cole, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law Hurt Locker is about a bomb Can viewers who don’t know or care much about soccer be convinced film comes toward the end—the heroine glances at a mirror squad in present-day Iraq, to see Damned United? Those who give it a whirl will discover a and sees herself. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

A Companion to Michael Haneke

A Companion to Michael Haneke Edited by Roy Grundmann A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication A Companion to Michael Haneke Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors The Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors survey key directors whose work together constitutes what we refer to as the Hollywood and world cinema canons. Whether Haneke or Hitchcock, Bigelow or Bergmann, Capra or the Coen brothers, each volume, comprised of 25 or more newly commissioned essays writ- ten by leading experts, explores a canonical, contemporary and/or controversial auteur in a sophisticated, authoritative, and multi-dimensional capacity. Individual volumes interrogate any number of subjects – the director’s oeuvre; dominant themes, well-known, worthy, and under-rated films; stars, collaborators, and key influences; reception, reputation, and above all, the director’s intellectual currency in the scholarly world. 1 A Companion to Michael Haneke, edited by Roy Grundmann 2 A Companion to Alfred Hitchcock, edited by Leland Poague and Thomas Leitch 3 A Companion to Rainer Fassbinder, edited by Brigitte Peucker 4 A Companion to Werner Herzog, edited by Brad Prager 5 A Companion to François Truffaut, edited by Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillian 6 A Companion to Pedro Almódovar, edited by Marvin D’Lugo and Kathleen Vernon 7 A Companion to John Ford, edited by Peter Lehman 8 A Companion to Jean Renoir, edited by Alistair Phillips and Ginette Vincendeau 9 A Companion to Louis Buñuel, edited by Robert Stone and Julian Daniel Gutierrez-Albilla 10 A Companion to Martin Scorsese, edited by Peter J. Bailey and Sam B. Girgus 11 A Companion to Woody Allen, edited by Aaron Baker A Companion to Michael Haneke Edited by Roy Grundmann A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition first published 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd except for editorial material and organization © 2010 Roy Grundmann Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. -

Toying with Twin Peaks: Fans, Artists and Re-Playing of a Cult-Series

CULTURE / RECEPTION / CONSUMPTION TOYING WITH TWIN PEAKS: FANS, ARTISTS AND RE-PLAYING OF A CULT-SERIES KATRIINA HELJAKKA Name Katriina Heljakka and again through mimetic practices such as re-creation of Academic centre School of History, Culture and Arts Studies characters and through photoplay. Earlier studies indicate (Degree Program of) Cultural Production and Landscape that adults are showing increased interest in character toys Studies, University of Turku such as dolls, soft toys (or plush) and action figures and vari- E-mail address [email protected] ous play patterns around them (Heljakka 2013). In this essay, the focus is, on the one hand on industry-created Twin Peaks KEYWORDS merchandise, and on the other hand, fans’ creative cultivation Adult play; fandom; photoplay; re-playing; toy play; toys. and play with the series scenes and its characters. The aim is to shed light on the object practices of fans and artists and ABSTRACT how their creativity manifests in current Twin Peaks fandom. This article explores the playful dimensions of Twin Peaks The essay shows how fans of Twin Peaks have a desire not only (1990-1991) fandom by analyzing adult created toy tributes to influence how toyified versions of e.g. Dale Cooper and the to the cult series. Through a study of fans and artists “toy- Log Lady come to existence, but further, to re-play the series ing” with the characters and story worlds of Twin Peaks, I will by mimicking its narrative with toys. demonstrate how the re-playing of the series happens again 25 SERIES VOLUME I, Nº 2, WINTER 2016: 25-40 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/6589 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X PARATEXTS, FANDOMS AND THE PERSISTENCE OF TWIN PEAKS CULTURE / RECEPTION / CONSUMPTION > KATRIINA HELJAKKA TOYING WITH TWIN PEAKS: FANS, ARTISTS AND RE-PLAYING OF A CULT-SERIES FIGURE 1. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ AWARDS/NOMINATIONS MTV Hip Hop Video - Black Eyed Peas “My Humps” MTV Best New Artist in a Vide - Sean Paul “Get Busy” (Nominee) TELEVISION/FILM King Of The Dancehall (Creative Director) Dir. Nick Cannon American Girl: Saige Paints The Sky Dir. Vince Marcello/Martin Chase Prod. American Girl: Alberta Dir. Vince Marcello Sparkle (Co-Chor.) Dir. Salim Akil En Vogue: An En Vogue Christmas Dir. Brian K. Roberts/Lifetime Tonight SHow w Gwen Stefani (Co-Chor.) NBC The X Factor (Associate Chor.) FOX Cheetah Girls 3: One World (Co-Chor.) Dir. Paul Hoen/Disney Channel Make It Happen (Co-Chor.) Dir. Darren Grant New York Minute Dir. D. Gorgon American Music Awards w/ Fergie (Artistic Director) ABC/Dick Clark Productions Divas Celebrate Soul (Co-Chor.) VH1 So You Think You Can Dance Canada Season 1-4 CTV Teen Choice Awards w/ Will.I.Am FOX American Idol w/ Jordin Sparks FOX American Idol w/ Will.I.Am FOX Superbowl XLV Halftime Show w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX/NFL Soul Train Awards BET Idol Gives Back w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX Grammy Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) CBS / AEG Ehrlich Ventures NFL Thanksgiving Motown Tribute (Co-Chor.) CBS/NFL American Music Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Dick Clark Productions BET Hip Hop Awards (Co-Chor.) BET NFL Kickoff Concert w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) NFL Oprah w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Harpo Teen Choice Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas