Master-S-Thesis--Yiting-He.Pdf (2.263Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washoku Guidebook(PDF : 3629KB)

和 食 Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese Itadaki-masu WASHOKU - cultures that should be preserved What exactly is WASHOKU? Maybe even Japanese people haven’t thought seriously about it very much. Typical washoku at home is usually comprised of cooked rice, miso soup, some main and side dishes and pickles. A set menu of grilled fish at a downtown diner is also a type of washoku. Recipes using cooked rice as the main ingredient such as curry and rice or sushi should also be considered as a type of washoku. Of course, washoku includes some noodle and mochi dishes. The world of traditional washoku is extensive. In the first place, the term WASHOKU does not refer solely to a dish or a cuisine. For instance, let’s take a look at osechi- ryori, a set of traditional dishes for New Year. The dishes are prepared to celebrate the coming of the new year, and with a wish to be able to spend the coming year soundly and happily. In other words, the religion and the mindset of Japanese people are expressed in osechi-ryori, otoso (rice wine for New Year) and ozohni (soup with mochi), as well as the ambience of the people sitting around the table with these dishes. Food culture has been developed with the background of the natural environment surrounding people and culture that is unique to the country or the region. The Japanese archipelago runs widely north and south, surrounded by sea. 75% of the national land is mountainous areas. Under the monsoonal climate, the four seasons show distinct differences. -

Rethinking Decentralized Managerialism in the Taipei Shilin Night Market Management Research and Practice Vol

Chiu C. mrp.ase.ro RETHINKING DECENTRALIZED MANAGERIALISM IN THE TAIPEI SHILIN NIGHT MARKET MANAGEMENT RESEARCH AND PRACTICE VOL. 6 ISSUE 3 (2014) PP: 66-87 ISSN 2067- 2462 RETHINKING DECENTRALIZED MANAGERIALISM IN THE TAIPEI SHILIN NIGHT MARKET Chihsin CHIU Department of Landscape Architecture, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan [email protected] 2014 Abstract This paper develops the concept of "decentralized managerialism" to examine the municipal policies regulating the Taipei Shilin Night Market. The concept highlights the roles of managerial autonomy and political-economic structures previously overlooked by urban managerialism. The process of decentralization evolves mainly over two stages - self-management and private management. By organizing self-managed alliances, street vendors appropriated public and private property by dealing with the municipality and local community in legal and extralegal situations in ways that supported their operations. The municipality compromised vendors' self- September management by demanding that they be licensed and registered and by building a new market. The stage of / private management begins when the municipality officially permits vending in a district by requiring vendors to 3 rent storefront arcades from a community alliance made of local property owners that allocate vending units. In the name of reallocating pre-existing extralegal street vendors, the project privileges property owners‟ profits over street vendors‟ needs for space. Field research has found that most unlicensed vendors continue occupying streets even after they are provided with legitimate vending units; five retailers in the business improvement district have rejected the arcade allocation plan by mobilizing their own social network. Shoppers continue trading with vendors outside of the district. -

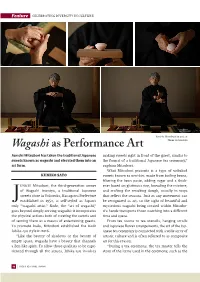

Wagashi As Performance

Feature CELEBRATING DIVERSITY IN CULTURE Junichi Mitsubori in action Photos: Kumazo Kato Wagashi as Performance Art Junichi Mitsubori has taken the traditional Japanese making sweets right in front of the guest, similar to sweets known as wagashi and elevated them into an the format of a traditional Japanese tea ceremony,” art form. explains Mitsubori. What Mitsubori presents is a type of unbaked KUMIKO SATO sweets known as neri-kiri, made from boiling beans, filtering the bean paste, adding sugar and a thick- unichi Mitsubori, the third-generation owner ener based on glutinous rice, kneading the mixture, of Wagashi Izumiya, a traditional Japanese and crafting the resulting dough, usually in ways sweets store in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture that reflect the seasons. Just as any movement can established in 1954, is self-styled as Japan’s be recognized as art, so the sight of beautiful and Jonly “wagashi artist.” Kado, the “art of wagashi,” mysterious wagashi being created within Mitsubo- goes beyond simply serving wagashi; it incorporates ri’s hands transports those watching into a different the physical actions both of creating the sweets and time and space. of serving them as a means of entertaining guests. From tea rooms to tea utensils, hanging scrolls To promote kado, Mitsubori established the Kado and Japanese flower arrangements, the art of the Jap- Ichika-ryu style in 2016. anese tea ceremony is connected with a wide array of “Like the beauty of shadows or the beauty of artistic culture and is often referred to as composite empty space, wagashi have a beauty that channels art for this reason. -

20180910 Matcha ENG.Pdf

Matcha served with wagashi Sencha served with wagashi Whole tea leaves ground into fine, ceremonial grade Choose from three excellent local teas curated by powder and whipped into a foamy broth using a our expert staff. Select one Kagoshima wagashi to method unchanged for over 400 years. Choose one accompany your tea for a refreshing break. Kagoshima wagashi to accompany your drink for the perfect pairing of bitter and sweet. ¥1,000 ¥850 Please choose your tea and wagashi from the following pages. All prices include tax. Please choose your sencha from the options below. Chiran-cha Tea from fields surrounding the samurai town of Chiran. Slightly sweet with a clean finish. Onejime-cha Onejime produces the earliest first flush tea in Kagoshima. Sharp, clean flavour followed by a gently lingering bitterness. Kirishima Organic Matcha The finest organically cultivated local matcha from the mountains of Kirishima. Full natural flavour with a slightly astringent edge. Oku Kirishima-cha Tea from the foothills of the Kirishima mountain range. Balanced flavour with refined umami and an astringent edge. Please choose your wagashi from the options below. Seasonal Namagashi(+¥200) Akumaki Sweets for the tea ceremony inspired by each season. Glutinous rice served with sweet toasted soybean Ideal with a refreshing cup of matcha. flour. This famous snack was taken into battle by tough Allergy information: contains yam Satsuma samurai. Allergy information: contains soy Karukan Hiryu-zu Local yams combined with refined rice flour and white Sweet bean paste, egg yolk, ginkgo nuts, and shiitake sugar to create a moist steamed cake. Created 160 mushrooms are combined in this baked treat that has years ago under the orders of Lord Shimadzu Nariakira. -

Read Book Wagashi and More: a Collection of Simple Japanese

WAGASHI AND MORE: A COLLECTION OF SIMPLE JAPANESE DESSERT RECIPES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cooking Penguin | 72 pages | 07 Feb 2013 | Createspace | 9781482376364 | English | United States Wagashi and More: A Collection of Simple Japanese Dessert Recipes PDF Book Similar to mochi, it is made with glutinous rice flour or pounded glutinous rice. Tourists like to buy akafuku as a souvenir, but it should be enjoyed quickly, as it expires after only two days. I'm keeping this one a little under wraps for now but if you happen to come along on one of my tours it might be on the itinerary Next to the velvety base, it can also incorporate various additional ingredients such as sliced chestnuts or figs. For those of you who came on the inaugural Zenbu Ryori tour - shhhhhhhh! Well this was a first. This classic mochi variety combines chewy rice cakes made from glutinous rice and kinako —roasted soybean powder. More about Hishi mochi. The sweet and salty goma dango is often consumed in August as a summer delicacy at street fairs or in restaurants. The base of each mitsumame are see-through jelly cubes made with agar-agar, a thickening agent created out of seaweed. Usually the outside pancake-ish layer is plain with a traditional filling of sweet red beans. Forgot your password? The name of this treat consists of two words: bota , which is derived from botan , meaning tree peony , and mochi , meaning sticky, pounded rice. Dessert Kamome no tamago. Rakugan are traditional Japanese sweets prepared in many different colors and shapes reflecting seasonal, holiday, or regional themes. -

Ach Food Companies Inc. Athena Foods Atlantic Beverage Company

ACH FOOD COMPANIES INC. BOOTH # 184 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 31340 24/1 LB CORN STARCH (ARGO) Case 2001561 $0.50 40614 4/1 GL SYRUP CORN SYRUP RED NO HFCS (KARO) Case 2010736 $2.00 AJINOMOTO BOOTH # 186 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 70804 6/4 LB APTZR MOZZARELLA STICK BREADED (FRED'S) Case 205120 $0.50 71851 6/2 LB APTZR GOUDA SMK BACON BITE (FRED'S) Case 0142020 $0.50 71853 4/4 LB APTZR PICKLE SPEAR GRL&ONION (FRED'S) Case 2270120 $0.50 A1001 TOASTED ONION BATTERED GREEN BEAN Case 0275720 $0.50 A1002 6/2 LB PICKLE CHIP BATTERED Case 0274120 $0.50 A1003 CHEESE CURD BATTERED Case 0606420 $0.50 ATHENA FOODS BOOTH # 191 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 42570 4/8 LB DRSNG MEDITERRANEAN (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NMD 42572 4/8 LB DRSNG GINGER SOY (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NGSD 42574 4/8 LB DRSNG BALSAMIC VINIAGRETTE (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NBSD 42576 4/8 LB DRSNG POPPYSEED (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NPSD 42578 4/8 LB DRSNG CAESAR VEGAN (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NVSD 42760 12/13 OZ DRSNG SHIELD'S RETAIL (SHIELDS) Case 1312NSD 73322 4/8 LB SAUCE CHEESE (SWT LORAIN) Case 12804NCS 73324 4/3 LB PESTO FROZEN (SWT LORAIN) Case 4804NSP 74340 18/12 ct QUICHE FRZ SPINACH ATHN (ATHENA FOO) Case 1218NSQ ATLANTIC BEVERAGE COMPANY BOOTH # 196 Item # Description Unit MFG # Allowance QTY 12001 6/#10 BEAN BLACK #10 (SUNFIELD) Case 700250 12018 6/#10 OLIVE BLACK SLICED SPANISH (ASSAGIO) Case 700890 13219 6/108 OZ PINEAPPLE TIDBIT #10 (SUNFIELD) Case 703076 33210 4/6 LB SEASONING LEMON PEPPER (ASSAGIO) Case 708200 40841 4/1 GL SAUCE HOT FRANK'S (FRENCHS) Case 05560 40844 4/1 GL SAUCE HOT BUFFALO WING FRANKS (FRENCHS) Case 74161 41509 1/2000 CT SWEETNER (SPLENDA) Case 822413 Tuesday, September 3, 2019 Page 1 of 18 41573 4/1 GL PEPPER PEPPERONCINI (CORCEL) Case 701280 42633 1/12 KG OLIVE KALAMATA X LARGE 201/23 (CORCEL) Pail 701120 BARILLA GROUP INC. -

170307 Yummy Taiwan-161202-1-D

Phone: 951-9800 Toll Free:1-877-951-3888 E-mail: [email protected] www.airseatvl.com 50 S. Beretania Street, Suite C - 211B, Honolulu, HI 96813 Belly-God's Yummy Yummy Tour: Taiwan Series Second Taste of Formosa ***Unforgettable Culinary Delicacies*** Taiwan Cities Covered: Taoyuan (Taipei), Nantou, Chiayi, Kaohsiung, Taitung, Hualien, Yilan (Jiaoxi) Tour Package Includes * International Flight from Honolulu Traveling Dates: * Deluxe Hotel Accommodations (Based on Double Occupancy) * Admissions and All Meals as Stated Mar 7– 15, 2017 Circle Island Tour to Visit 3 Most Popular Ranking Scenic Spots in Taiwan: (9 Days) * • Sun Moon Lake with Boat Ride • Alishan (Mt. Ali) National Scenic Area with Forest Railway • Taroko Marble Gorge Price per person: Hands-on Experience: * • Paper Making • Bubble Milk Tea Natural Hot Spring Hotels (3 Nights) $ * 2,688 Night Market Incl: Tax & Fuel Charge * Local Specialty: Shaoxing Cuisine, Fruit Meal, Green Tea * Cuisine, All You Can Eat Hot Pot, Truku Cuisine, Crock Pot Soup, Single Supp: $700 Taiwanese Dim Sum…. "Ni Hao" or "Welcome" to Taiwan! During Taiwan’s long history, prehistoric people, indigenous tribes, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, and Han Chinese have successively occupied Taiwan, creating a varied culture and developing different local customs and traditions along the way. We will encounter all aspects of this beautiful country's multifaceted cultures. In Taiwan, cooking techniques from all areas of China have merged: the Taiwanese have not only mastered the traditional local Chinese specialties, but have also used traditional techniques to develop new culinary treats. We will taste many different kinds of cuisines here. Taiwan is also ranked among the world's top hot spring sites: the island Onsen Spa can proudly regard itself as one of the regions with the highest concentration and greatest variety of hot springs in the world. -

Favorite Foods of the World.Xlsx

FAVORITE FOODS OF THE WORLD - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Fourth Round Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Blintzes Duck Confit Papadums Laksa Jambalaya Burrito Cornish Pasty Bulgogi Nori Torta Vegemite Toast Crepes Tagliatelle al Ragù Bouneschlupp Potato Pancakes Hummus Gazpacho Lumpia Philly Cheesesteak Cannelloni Tiramisu Kugel Arepas Cullen Skink Börek Hot and Sour Soup Gelato Bibimbap Black Forest Cake Mousse Croissants Soba Bockwurst Churros Parathas Cream Stew Brie de Meaux Hutspot Crab Rangoon Cupcakes Kartoffelsalat Feta Cheese Kroppkaka PBJ Sandwich Gnocchi Saganaki Mochi Pretzels Chicken Fried Steak Champ Chutney Kofta Pizza Napoletana Étouffée Satay Kebabs Pelmeni Tandoori Chicken Macaroons Yakitori Cheeseburger Penne Pinakbet Dim Sum DIVISION ONE DIVISION TWO Lefse Pad Thai Fastnachts Empanadas Lamb Vindaloo Panzanella Kombu Tourtiere Brownies Falafel Udon Chiles Rellenos Manicotti Borscht Masala Dosa Banh Mi Som Tam BLT Sanwich New England Clam Chowder Smoked Eel Sauerbraten Shumai Moqueca Bubble & Squeak Wontons Cracked Conch Spanakopita Rendang Churrasco Nachos Egg Rolls Knish Pastel de Nata Linzer Torte Chicken Cordon Bleu Chapati Poke Chili con Carne Jollof Rice Ratatouille Hushpuppies Goulash Pernil Weisswurst Gyros Chilli Crab Tonkatsu Speculaas Cookies Fish & Chips Fajitas Gravlax Mozzarella Cheese -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

Distribución Consumo

Distribución Y Consumo 98AÑO 18 - MARZO ✟ ABRIL 2008 Las TIC en la gestión logística Criterios para confeccionar la carta de vinos del restaurante Alimentos de España. Castilla y León Los envases dan forma a los nuevos productos Mercados en origen de frutas y hortalizas AZALEA COSMETIC 27/3/07 09:02 Página 1 Sumario_98:SUMARIO77 4/4/08 09:45 Página 3 Distribución AÑO 18 - MARZO ■ ABRIL 2008 YConsumo 98 EDITA MERCASA PRESIDENTE IGNACIO CRUZ ROCHE DIRECTOR Distribución y creación de valor Los costes de la cadena de ÁNGEL JUSTE MATA en la comercialización en origen distribución de productos COORDINADORES DEL CONSEJO DE REDACCIÓN de las frutas y hortalizas en fresco hortofrutícolas en fresco JAVIER CASARES RIPOL 5 Joan Mir Piqueras y ALFONSO REBOLLO ARÉVALO Francisco Borras Escribá 55 CONSEJO DE REDACCIÓN JOSÉ LUIS MARRERO CABRERA El sistema de comercialización JORGE JORDANA BUTTICAZ DE POZAS JOSÉ ANTONIO PUELLES PÉREZ en origen de las frutas y Tecnologías de la información IGNACIO CRUZ ROCHE hortalizas en fresco y la comunicación en la TOMÁS HORCHE TRUEBA VÍCTOR J. MARTÍN CERDEÑO Emilia Martínez Castro y gestión logística CÉSAR GINER Alfonso Rebollo Arévalo 8 David Servera Francés e ANGEL FERNÁNDEZ NOGALES Irene Gil Saura 67 PUBLICIDAD Y ADMINISTRACIÓN MARTÍN CASTRO ORTIZ Las actividades de acabado del producto y auxiliares de la Los envases dan forma a los SECRETARÍA DE REDACCIÓN nuevos productos LAURA ONCINA producción en la cadena de valor JOSÉ LUIS FRANCO hortofrutícola Sylvia Resa 84 JULIO FERNÁNDEZ ANGULO Manuel Sánchez Pérez y FOTOGRAFÍA -

Food Byways: the Sugar Road by Masami Ishii

Vol. 27 No. 3 October 2013 Kikkoman’s quarterly intercultural forum for the exchange of ideas on food SPOTLIGHT JAPAN: JAPANESE STYLE: Ohagi and Botamochi 5 MORE ABOUT JAPANESE COOKING 6 Japan’s Evolving Train Stations 4 DELECTABLE JOURNEYS: Nagano Oyaki 5 KIKKOMAN TODAY 8 THE JAPANESE TABLE Food Byways: The Sugar Road by Masami Ishii This third installment of our current Feature series traces Japan’s historical trade routes by which various foods were originally conveyed around the country. This time we look at how sugar came to make its way throughout Japan. Food Byways: The Sugar Road From Medicine to Sweets to be imported annually, and it was eventually According to a record of goods brought to Japan from disseminated throughout the towns of Hakata China by the scholar-priest Ganjin (Ch. Jianzhen; and Kokura in what is known today as Fukuoka 688–763), founder of Toshodaiji Temple in Nara, Prefecture in northern Kyushu island. As sugar cane sugar is thought to have been brought here in made its way into various regions, different ways the eighth century. Sugar was considered exceedingly of using it evolved. Reflecting this history, in the precious at that time, and until the thirteenth 1980s the Nagasaki Kaido highway connecting the century it was used solely as an ingredient in the cities of Nagasaki and Kokura was dubbed “the practice of traditional Chinese medicine. Sugar Road.” In Japan, the primary sweeteners had been After Japan adopted its national seclusion laws maltose syrup made from glutinous rice and malt, in the early seventeenth century, cutting off trade and a sweet boiled-down syrup called amazura made and contact with much of the world, Nagasaki from a Japanese ivy root. -

The Culinary Institute of America at Greystone Napa Valley, California

Presents 13th Annual Worlds of Flavor International Conference & Festival JAPAN: FLAVORS OF CULTURE From Sushi and Soba to Kaiseki, A Global Celebration of Tradition, Art, and Exchange November 4-6, 2010 The Culinary Institute of America at Greystone Napa Valley, California PRESENTERS & GUEST CHEFS BIOS TARO ABE is the second generation chef of Washoku OTAFUKU, a restaurant that specializes in the regional cuisine of Akita, including ―Kiritanpo,‖ a unique rice pot dish. Chef Abe’s cuisine is representative of this Northern Japan region that is famous for rice farming and sake brewing along with other agriculture, fishing, and forestry. (Akita, Japan) ELIZABETH ANDOH is an American writer and lecturer specializing in Japanese food and culture. She owns and operates ―A Taste of Culture,‖ a culinary arts program in Tokyo and Osaka. Ms. Andoh is the only non-Japanese member of the prestigious Japan Food Journalists Association and also contributes to American publications, such as the New York Times. As a lecturer on historical and cultural aspects of Japanese society and cuisine, she conducts workshops and speaks frequently to industry and general-interest audiences on both sides of the Pacific. Her 2005 cookbook, Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen (Ten Speed Press) won an IACP Jane Grigson award for distinguished scholarship, and was nominated for a James Beard Foundation award. 2010 Worlds of Flavor Presenter & Guest Chef Biographies Updated August 30, 2010 | Page 1 of 21 Ms. Andoh’s new cookbook, KANSHA: Celebrating Japan’s Vegan & Vegetarian Traditions, will be released by Ten Speed Press on October 19, 2010. Ms.