India's Act East Policy: Embedding the Andamans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar

Andaman Islands: Development or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar DEVELOPMENT OR DESPOILATION? The Andaman Islands under colonial and postcolonial regimes M.V. KRISHNAKUMAR Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi <[email protected]> Abstract The last quarter of the 19th Century marked an important watershed in the history of the Andaman Islands. The establishment of a penal settlement and an Imperial forestry service, along with other radical changes in the islands’ traditional economy and society, completely transformed the basic pattern of their forest resource use and entire system of forest management. These colonial policies, directly or indirectly, had a drastic impact on the indigenous population and island ecology. This article analyses the sources of environmental change in the Andaman Islands by examining the general ecological impacts of the state initiated development programmes. It also analyses the ‘civilising missions’ and forestry operations undertaken by British colonial administrators as well as the Indian state’s development initiatives under the ‘Five Year Plans’ that followed Indian independence in 1947. Keywords Andaman Islands, forestry, development, environmental change, Andaman tribes Introduction On December 26th 2004 a tsunami triggered by an earthquake off the south east coast of Sumatra swept across the Indian Ocean swamping many low-lying coastal areas and causing death, destruction of properties and infrastructure and despoliation of crops. Amongst those territories worst affected by the surge were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. When Indian prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh visited the islands in the immediate aftermath of the flooding he identified that the project to reconstruct and rehabilitate coastal areas of islands provided the opportunity for a ‘New Andamans’ in which sustainable agriculture and fishery enterprises could exist in harmony with the natural environment. -

The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire*

IRSH 63 (2018), Special Issue, pp. 25–43 doi:10.1017/S0020859018000202 © 2018 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire* C LARE A NDERSON School of History, Politics and International Relations University of Leicester University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article explores the British Empire’s configuration of imprisonment and transportation in the Andaman Islands penal colony. It shows that British governance in the Islands produced new modes of carcerality and coerced migration in which the relocation of convicts, prisoners, and criminal tribes underpinned imperial attempts at political dominance and economic development. The article focuses on the penal transportation of Eurasian convicts, the employment of free Eurasians and Anglo-Indians as convict overseers and administrators, the migration of “volunteer” Indian prisoners from the mainland, the free settlement of Anglo-Indians, and the forced resettlement of the Bhantu “criminal tribe”.It examines the issue from the periphery of British India, thus showing that class, race, and criminality combined to produce penal and social outcomes that were different from those of the imperial mainland. These were related to ideologies of imperial governmentality, including social discipline and penal practice, and the exigencies of political economy. INTRODUCTION Between 1858 and 1939, the British government of India transported around 83,000 Indian and Burmese convicts to the penal colony of the Andamans, an island archipelago situated in the Bay of Bengal (Figure 1). -

Arachnozoogeographical Analysis of the Boundary Between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region

Historia naturalis bulgarica, 23: 5-36, 2016 Arachnozoogeographical analysis of the boundary between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region Petar Beron Abstract: This study aims to test how the distribution of various orders of Arachnida follows the classical subdivision of Asia and where the transitional zone between the Eastern Palearctic (Holarctic Kingdom) and the Indomalayan Region (Paleotropic) is situated. This boundary includes Thar Desert, Karakorum, Himalaya, a band in Central China, the line north of Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. The conclusion is that most families of Arachnida (90), excluding most of the representatives of Acari, are common for the Palearctic and Indomalayan Regions. There are no endemic orders or suborders in any of them. Regarding Arach- nida, their distribution does not justify the sharp difference between the two Kingdoms (Paleotropical and Holarctic) in Eastern Eurasia. The transitional zone (Sino-Japanese Realm) of Holt et al. (2013) also does not satisfy the criteria for outlining an area on the same footing as the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms. Key words: Palearctic, Indomalayan, Arachnozoogeography, Arachnida According to the classical subdivision the region’s high mountains and plateaus. In southern Indomalayan Region is formed from the regions in Asia the boundary of the Palearctic is largely alti- Asia that are south of the Himalaya, and a zone in tudinal. The foothills of the Himalaya with average China. North of this “line” is the Palearctic (consist- altitude between about 2000 – 2500 m a.s.l. form the ing og different subregions). This “line” (transitional boundary between the Palearctic and Indomalaya zone) is separating two kingdoms, therefore the dif- Ecoregions. -

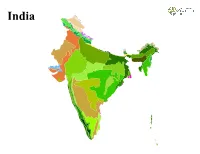

R Graphics Output

India India LEGEND Ecoregion Andaman Islands rain forests Mizoram−Manipur−Kachin rain forests Aravalli west thorn scrub forests Narmada Valley dry deciduous forests Baluchistan xeric woodlands Nicobar Islands rain forests Brahmaputra Valley semi−evergreen forests North Deccan dry deciduous forests Central Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Central Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe North Western Ghats montane rain forests Chhota−Nagpur dry deciduous forests Northeast Himalayan subalpine conifer forests Chin Hills−Arakan Yoma montane forests Northeast India−Myanmar pine forests Deccan thorn scrub forests Northern Triangle temperate forests East Deccan dry−evergreen forests Northwestern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows East Deccan moist deciduous forests Orissa semi−evergreen forests Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests Rock and Ice Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests Godavari−Krishna mangroves South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests South Western Ghats montane rain forests Himalayan subtropical pine forests Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests Indus River Delta−Arabian Sea mangroves Sundarbans mangroves Karakoram−West Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe Terai−Duar savanna and grasslands Khathiar−Gir dry deciduous forests Thar desert Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Malabar Coast moist forests Western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Maldives−Lakshadweep−Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests Western Himalayan broadleaf forests Meghalaya subtropical forests Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

Chapter 2 Introduction to the Geography and Geomorphology Of

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on February 7, 2017 Chapter 2 Introduction to the geography and geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar Islands P. C. BANDOPADHYAY1* & A. CARTER2 1Department of Geology, University of Calcutta, 35 Ballygunge Circular Road, Kolkata-700019, India 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The geography and the geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar accretionary ridge (islands) is extremely varied, recording a complex interaction between tectonics, climate, eustacy and surface uplift and weathering processes. This chapter outlines the principal geographical features of this diverse group of islands. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license The Andaman–Nicobar archipelago is the emergent part of a administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Group. Other long ridge which extends from the Arakan–Yoma ranges of islands of importance are Katchal, Camorta, Nancowry, Till- western Myanmar (Burma) in the north to Sumatra in the angchong, Chowra, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. The lat- south. To the east the archipelago is flanked by the Andaman ter is the largest covering 1045 km2. Indira Point on the south Sea and to the west by the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1.1). A coast of Great Nicobar Island, named after the honorable Prime c. 160 km wide submarine channel running parallel to the Minister Smt Indira Gandhi of India, lies 147 km from the 108 N latitude between Car Nicobar and Little Andaman northern tip of Sumatra and is India’s southernmost point. -

Impacts of Invasive Alien Species on Island Ecosystems of India with Special Reference to Andaman Group of Islands - National Biodiversity Authority, Chennai

Authors S. Sandilyan, B. Meenakumari, A. Biju Kumar & Karthikeyan Vasudevan Citation Sandilyan, S., Meenakumari, B., Biju Kumar, A. and Karthikeyan Vasude- van. 2018. Impacts of invasive alien species on island ecosystems of India with special reference to Andaman group of islands - National Biodiversity Authority, Chennai. Corresponding Author Sandilyan, S. <[email protected]> Copyright @ National Biodiversity Authority, Chennai. ISBN No.: 978-81-932753-5-1 Published by Centre for Biodiversity Policy and Law (CEBPOL) National Biodiversity Authority 5th Floor, TICEL Biopark, CSIR Road, Taramani Chennai 600 113, Tamil Nadu Website: www.nbaindia.org/cebpol Layout and Design: N.Singaram Information Technology Executive, CEBPOL Disclaimer: This publications is prepared as an initiative under CEBPOL programme. All the views expressed in this publication are based on established legal principles. Any error or lapse is purely unintended and inconsequential and shall not make either the NBA or the CEBPOL liable for the same. Some pictures and images included in this publication are sourced from public domain. This publications is purely for non-commercial purposes including awareness creation and capacity building. Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 II. Introduction to Islands .......................................................................... 5 a. Biological Importance of Islands .................................................. 8 b. Indian Islands -

FAQ Welcome to Andamans. Your Convenience Is Our Prime Concern. Please Read Below to Get Answers to Your Most Frequent Queries A

FAQ Welcome to Andamans. Your convenience is our prime concern. Please read below to get answers to your most frequent queries and prepare you trip to Andamans with these practical advices and tips. 1. Where Andaman Nicobar Islands Locates? The Andaman and Nicobar Islands, located in the south-east of the Indian mainland geographically, float in splendid isolation in the Bay of Bengal. Once a hill range extending from Myanmar to Indonesia, these picturesque undulating islands, islets numbering around 836, are covered with dense rain-fed, damp and evergreen forests and endless varieties of exotic flora and fauna. 2. How to find Andaman on map? Coordinates: 11.7401° N, 92.6586° E 3. How to Reach Andaman? By Air and Ship The Veer Savarkar Airport, an International Airport is located in the capital town of Port Blair, the gateway to Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Port Blair, is connected with Chennai, Kolkata, New Delhi and Bangalore by air. Air India, Go Air, Indigo, Vistara & Spice Jet Airlines operate regular flights. Foreign chartered flights are also permitted to land at Port Blair subject to the fulfilment of guidelines of the Directorate General of Civil Aviation. Regular passenger ship services are available to Port Blair from Chennai, Kolkata and Visakhapatnam and back. There are three to four sailings every month from Kolkata and Chennai to Port Blair and vice-versa. There is only one sailing for Visakhapatnam in a month. The voyage takes about 50 to 60 hours during fair weather. 4. Is the passport required for Andaman? No, Indian citizens do not require a passport to visit Andaman. -

Unique Origin of Andaman Islanders: Insight from Autosomal Loci

J Hum Genet (2006) 51:800–804 DOI 10.1007/s10038-006-0026-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Unique origin of Andaman Islanders: insight from autosomal loci K. Thangaraj Æ G. Chaubey Æ A. G. Reddy Æ V. K. Singh Æ L. Singh Received: 9 April 2006 / Accepted: 1 June 2006 / Published online: 19 August 2006 Ó The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Our mtDNA and Y chromosome studies Introduction lead to the conclusion that the Andamanese ‘‘Negrito’’ mtDNA lineages have survived in the Andaman Is- The ‘‘Negrito’’ populations found scattered in parts of lands in complete genetic isolation from other South southern India, the Andaman Islands, Malaysia and the and Southeast Asian populations since the initial set- Philippines are considered to be the relic of early tlement of the region by the out-of-Africa migration. In modern humans and hence assume considerable order to obtain a robust reconstruction of the evolu- anthropological and genetic importance. Their gene tionary history of the Andamanese, we carried out a pool is slowly disappearing either due to assimilation study on the three aboriginal populations, namely, the with adjoining populations, as in the case of the Se- Great Andamanese, Onge and Nicobarese, using mang of Malaysia and Aeta of the Philippines, or due autosomal microsatellite markers. The range of alleles to their population collapse, as is evident in the case of (7–31.2) observed in the studied population and het- the aboriginals of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman erozygosity values (0.392–0.857) indicate that the se- and Nicobar Islands are inhabited by six enigmatic lected STR markers are highly polymorphic in all the indigenous tribal populations, of which four have been three populations, and genetic variability within the characterized traditionally as ‘‘Negritos’’ (the Jarawa, populations is significantly high, with a mean gene Onge, Sentinelese and Great Andamanese) and two as diversity of 77%. -

LIFE HISTORY of PACHLIOPTA RHODIFER Das (Oberthiir), Papilio Mayo Atkinson, Or Pachliopta Rhodifer (Butler)

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 48(2), 1994, 111-120 LIFE HISTORY OF PACHLIOPTA RHODIFER (PAPILIONIDAE: TROIDINI) K, VEENAKUMARI AND PRASHANTH MOHANRAJ Central Agricultural Research Institute, P. B. No. 181, Port Blair, 744101, Andaman Islands, India ABSTRACT. The Andaman c1ubtail, Pachliopta rhodifer (Butler), is one of, three papilionids endemic to the Andaman and Nicobar islands, India. This elegant red-bodied swallowtail, with its unique red spatulate tail, previously was known only from the imago. We detail the life history of this species and discuss implications for butterfly conservation in these islands. Additional key words: Aristolochiaceae, butterfly conservation, Andaman Islands, Nicobar Islands, India. The Andaman and Nicobar islands have been identified as one of the provinces of the Indomalayan biogeographic realm requiring urgent attention to ensure adequate protection of their disltinctive biological communities (Anonymous 1985, ICBP 1992). These islands are situated in the Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean, between 6-14°N latitude and 92- 94°E longitude, and consist of 306 islands. They stretch over 700 km and occupy a total area of 8249 km2 (Anonymous 1986). The Andamans are separated from the Nicobars by the Ten Degree Channel, a distance of about 100 km. The two island groups have characteristic biotic elements, with each island group harboring a set of unique endemics (Anonymous 1986, Rao 1986). On the basis of the number of endemics found in a region, Collins and Morris (1985) rate the Andaman and Nicobar islands sixteenth out of a total of 51 critical swallowtail faunas worldwide. In spite of the high priority ranking, no attempt has been made to study the life histories, food plants, and other requirements of Graphium epaminon das (Oberthiir), Papilio mayo Atkinson, or Pachliopta rhodifer (Butler), the three endemic papilionids that are thought to be confined to Great Andaman (which includes the three neighboring islands of North, Mid dle, and South Andaman). -

Of Sea Level Rise Mediated by Climate Change 7 8 9 10 Shaily Menon ● Jorge Soberón ● Xingong Li ● A

The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com Biodiversity and Conservation Menon et al. 1 Volume 19, Number 6, 1599-1609, DOI: 10.1007/s10531-010-9790-4 1 2 3 4 5 Preliminary global assessment of biodiversity consequences 6 of sea level rise mediated by climate change 7 8 9 10 Shaily Menon ● Jorge Soberón ● Xingong Li ● A. Townsend Peterson 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 S. Menon 18 Department of Biology, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, Michigan 49401-9403 USA, 19 [email protected] 20 21 J. Soberón 22 Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research Center, The University of Kansas, 23 Lawrence, Kansas 66045 USA 24 25 X. Li 26 Department of Geography, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 USA 27 28 A. T. Peterson 29 Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research Center, The University of Kansas, 30 Lawrence, Kansas 66045 USA 31 32 33 34 Corresponding Author: 35 A. Townsend Peterson 36 Tel: (785) 864-3926 37 Fax: (785) 864-5335 38 Email: [email protected] 39 40 The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com | DOI: 10.1007/s10531-010-9790-4 Menon et al. Biodiversity consequences of sea level rise 2 41 Running Title: Biodiversity consequences of sea level rise 42 43 Preliminary global assessment of biodiversity consequences 44 of sea level rise mediated by climate change 45 46 Shaily Menon ● Jorge Soberón ● Xingong Li ● A. Townsend Peterson 47 48 49 Abstract Considerable attention has focused on the climatic effects of global climate change on 50 biodiversity, but few analyses and no broad assessments have evaluated the effects of sea level 51 rise on biodiversity. -

Flaked Glass Tools from the Andaman Islands and Australia

Flaked Glass Tools from the Andaman Islands and Australia ZARINE COOPER AND SANDRA BOWDLER BETWEEN THE FIFTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES, Europeans colonized many parts of the world that were already occupied by other people. Many of the previous landholders were people using stone-based technology. In the longer term, they were generally unable to hold their land in the face of invasion by people with metal and gunpowder technology. In the shorter term, however, there was often a period during which the indigenous people maintained their traditional lifestyle, but adapted elements of the new culture to its pursuance. One example of such adaptation is the use of glass to produce tools of a kind pre viously made out of stone by means of percussion, a technique known as flaking or knapping. Flaked glass artifacts dating to a period of culture contact between stone-flaking cultures and glass-producing cultures have been recorded in several countries. In this paper we discuss examples from the Andaman Islands and Western Australia to show how cultures with no historical relationship but a similar tech nological base made similar adaptive uses of a new material. While these exam ples are drawn from societies that survived into recent historical times with hunter-gatherer economies, it is possible that any culture with a knapping tech nology could have made similar adaptations. PROBLEMS OF IDENTIFICATION There is a problem in the identification of flaked glass artifacts, as noted by Beaumont (1961) for South Mrica. As he and earlier writers whom he cites point out, physical characteristics identical with those derived from human trimming are easily produced on fractured glass by accidental means.