Flaked Glass Tools from the Andaman Islands and Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Keyword List Contains Indian Ocean Place Names of Coral Reefs, Islands, Bays and Other Geographic Features in a Hierarchical Structure

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 8/9/2016 Indian Ocean This keyword list contains Indian Ocean place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. For example, the first name on the list - Bird Islet - is part of the Addu Atoll, which is in the Indian Ocean. The leading label - OCEAN BASIN - indicates this list is organized according to ocean, sea, and geographic names rather than country place names. The list is sorted alphabetically. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Indian Ocean” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. For example, the first place name “Bird Islet” has a unique identifier of “00S073E0013”. From that we see that Bird Islet is located at 00 degrees south (S) and 073 degrees east (E). It is place number 0013 at that latitude and longitude. (Note: some long lines wrapped, placing the unique identifier on the following line.) This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bird Islet (00S073E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bushy Islet (00S073E0014) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Fedu Island (00S073E0008) -

Development Or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar

Andaman Islands: Development or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar DEVELOPMENT OR DESPOILATION? The Andaman Islands under colonial and postcolonial regimes M.V. KRISHNAKUMAR Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi <[email protected]> Abstract The last quarter of the 19th Century marked an important watershed in the history of the Andaman Islands. The establishment of a penal settlement and an Imperial forestry service, along with other radical changes in the islands’ traditional economy and society, completely transformed the basic pattern of their forest resource use and entire system of forest management. These colonial policies, directly or indirectly, had a drastic impact on the indigenous population and island ecology. This article analyses the sources of environmental change in the Andaman Islands by examining the general ecological impacts of the state initiated development programmes. It also analyses the ‘civilising missions’ and forestry operations undertaken by British colonial administrators as well as the Indian state’s development initiatives under the ‘Five Year Plans’ that followed Indian independence in 1947. Keywords Andaman Islands, forestry, development, environmental change, Andaman tribes Introduction On December 26th 2004 a tsunami triggered by an earthquake off the south east coast of Sumatra swept across the Indian Ocean swamping many low-lying coastal areas and causing death, destruction of properties and infrastructure and despoliation of crops. Amongst those territories worst affected by the surge were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. When Indian prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh visited the islands in the immediate aftermath of the flooding he identified that the project to reconstruct and rehabilitate coastal areas of islands provided the opportunity for a ‘New Andamans’ in which sustainable agriculture and fishery enterprises could exist in harmony with the natural environment. -

The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire*

IRSH 63 (2018), Special Issue, pp. 25–43 doi:10.1017/S0020859018000202 © 2018 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire* C LARE A NDERSON School of History, Politics and International Relations University of Leicester University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article explores the British Empire’s configuration of imprisonment and transportation in the Andaman Islands penal colony. It shows that British governance in the Islands produced new modes of carcerality and coerced migration in which the relocation of convicts, prisoners, and criminal tribes underpinned imperial attempts at political dominance and economic development. The article focuses on the penal transportation of Eurasian convicts, the employment of free Eurasians and Anglo-Indians as convict overseers and administrators, the migration of “volunteer” Indian prisoners from the mainland, the free settlement of Anglo-Indians, and the forced resettlement of the Bhantu “criminal tribe”.It examines the issue from the periphery of British India, thus showing that class, race, and criminality combined to produce penal and social outcomes that were different from those of the imperial mainland. These were related to ideologies of imperial governmentality, including social discipline and penal practice, and the exigencies of political economy. INTRODUCTION Between 1858 and 1939, the British government of India transported around 83,000 Indian and Burmese convicts to the penal colony of the Andamans, an island archipelago situated in the Bay of Bengal (Figure 1). -

Arachnozoogeographical Analysis of the Boundary Between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region

Historia naturalis bulgarica, 23: 5-36, 2016 Arachnozoogeographical analysis of the boundary between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region Petar Beron Abstract: This study aims to test how the distribution of various orders of Arachnida follows the classical subdivision of Asia and where the transitional zone between the Eastern Palearctic (Holarctic Kingdom) and the Indomalayan Region (Paleotropic) is situated. This boundary includes Thar Desert, Karakorum, Himalaya, a band in Central China, the line north of Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. The conclusion is that most families of Arachnida (90), excluding most of the representatives of Acari, are common for the Palearctic and Indomalayan Regions. There are no endemic orders or suborders in any of them. Regarding Arach- nida, their distribution does not justify the sharp difference between the two Kingdoms (Paleotropical and Holarctic) in Eastern Eurasia. The transitional zone (Sino-Japanese Realm) of Holt et al. (2013) also does not satisfy the criteria for outlining an area on the same footing as the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms. Key words: Palearctic, Indomalayan, Arachnozoogeography, Arachnida According to the classical subdivision the region’s high mountains and plateaus. In southern Indomalayan Region is formed from the regions in Asia the boundary of the Palearctic is largely alti- Asia that are south of the Himalaya, and a zone in tudinal. The foothills of the Himalaya with average China. North of this “line” is the Palearctic (consist- altitude between about 2000 – 2500 m a.s.l. form the ing og different subregions). This “line” (transitional boundary between the Palearctic and Indomalaya zone) is separating two kingdoms, therefore the dif- Ecoregions. -

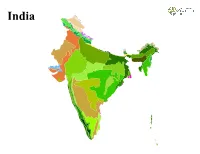

R Graphics Output

India India LEGEND Ecoregion Andaman Islands rain forests Mizoram−Manipur−Kachin rain forests Aravalli west thorn scrub forests Narmada Valley dry deciduous forests Baluchistan xeric woodlands Nicobar Islands rain forests Brahmaputra Valley semi−evergreen forests North Deccan dry deciduous forests Central Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Central Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe North Western Ghats montane rain forests Chhota−Nagpur dry deciduous forests Northeast Himalayan subalpine conifer forests Chin Hills−Arakan Yoma montane forests Northeast India−Myanmar pine forests Deccan thorn scrub forests Northern Triangle temperate forests East Deccan dry−evergreen forests Northwestern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows East Deccan moist deciduous forests Orissa semi−evergreen forests Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests Rock and Ice Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests Godavari−Krishna mangroves South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests South Western Ghats montane rain forests Himalayan subtropical pine forests Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests Indus River Delta−Arabian Sea mangroves Sundarbans mangroves Karakoram−West Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe Terai−Duar savanna and grasslands Khathiar−Gir dry deciduous forests Thar desert Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Malabar Coast moist forests Western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Maldives−Lakshadweep−Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests Western Himalayan broadleaf forests Meghalaya subtropical forests Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

North Andaman (Diglipur) Earthquake of 14 September 2002

Reconnaissance Report North Andaman (Diglipur) Earthquake of 14 September 2002 ATR Smith Island Ross Island Aerial Bay Jetty Diglipur Shibpur ATR Kalipur Keralapuran Kishorinagar Saddle Peak Nabagram Kalighat North Andaman Ramnagar Island Stewart ATR Island Sound Island Mayabunder Jetty Middle Austin Creek ATR Andaman Island Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208016 Field Study Sponsored by: Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi Printing of Report Supported by: United Nations Development Programme, New Delhi, India Dissemination of Report by: National Information Center of Earthquake Engineering, IIT Kanpur, India Copies of the report may be requested from: National Information Center for Earthquake Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208016 www.nicee.org Email: [email protected] Fax: (0512) 259 7866 Cover design by: Jnananjan Panda R ECONNAISSANCE R EPORT NORTH ANDAMAN (DIGLIPUR) EARTHQUAKE OF 14 SEPTEMBER 2002 by Durgesh C. Rai C. V. R. Murty Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208 016 Sponsored by Department of Science & Technology Government of India, New Delhi April 2003 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are sincerely thankful to all individuals who assisted our reconnaissance survey tour and provided relevant information. It is rather difficult to name all, but a few notables are: Dr. R. Padmanabhan and Mr. V. Kandavelu of Andaman and Nicobar Administration; Mr. Narendra Kumar, Mr. S. Sundaramurthy, Mr. Bhagat Singh, Mr. D. Balaji, Mr. K. S. Subbaian, Mr. M. S. Ramamurthy, Mr. Jina Prakash, Mr. Sandeep Prasad and Mr. A. Anthony of Andaman Public Works Department; Mr. P. Radhakrishnan and Mr. -

Chapter 2 Introduction to the Geography and Geomorphology Of

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on February 7, 2017 Chapter 2 Introduction to the geography and geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar Islands P. C. BANDOPADHYAY1* & A. CARTER2 1Department of Geology, University of Calcutta, 35 Ballygunge Circular Road, Kolkata-700019, India 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The geography and the geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar accretionary ridge (islands) is extremely varied, recording a complex interaction between tectonics, climate, eustacy and surface uplift and weathering processes. This chapter outlines the principal geographical features of this diverse group of islands. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license The Andaman–Nicobar archipelago is the emergent part of a administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Group. Other long ridge which extends from the Arakan–Yoma ranges of islands of importance are Katchal, Camorta, Nancowry, Till- western Myanmar (Burma) in the north to Sumatra in the angchong, Chowra, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. The lat- south. To the east the archipelago is flanked by the Andaman ter is the largest covering 1045 km2. Indira Point on the south Sea and to the west by the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1.1). A coast of Great Nicobar Island, named after the honorable Prime c. 160 km wide submarine channel running parallel to the Minister Smt Indira Gandhi of India, lies 147 km from the 108 N latitude between Car Nicobar and Little Andaman northern tip of Sumatra and is India’s southernmost point. -

Andaman Islands, India

Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery. 2019, 3(4): 398-405 © 2019 GCdataPR DOI:10.3974/geodp.2019.04.15 Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository www.geodoi.ac.cn Global Change Data Encyclopedia Andaman Islands, India Shen, Y.1 Liu, C.1* Shi, R. X.1 Chen, L. J.2 1. Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; 2. National Geomatics Center of China, Beijing 100830, China Keywords: Andaman Islands; Andaman and Nicobar Islands; Bay of Bengal; Indian Ocean; India; data encyclopedia Andaman Islands is the main part of the An- daman and Nicobar Islands. It belongs to the Indian Union Territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and its geo-location is 10°30′39″N–13°40′36″N, 92°11′55″E–94°16′ 38″E[1]. It is located between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea (Figure 1). It is separated from Coco Islands[2] by Coco Chanel at its north, and from Nicobar Islands[3] by Ten De- gree Chanel at its south. The Andaman Islands consists of Great Andaman Archipelago[4], Lit- tle Andaman Group[5], Ritchie’s Archipelago[6], [7] [8] East Volcano Islands and Sentinel Islands Figure 1 Map of Andaman Islands (Figure 2), with a total of 211 islands (islets, [1] (.kmz format) rocks) . The total area of the Andaman Islands is 5,787.79 km2, and the coastline is 2,878.77 km. Great Andaman Archipelago is the main part of Andaman Islands, and is the largest Ar- chipelago in Andaman Islands. -

Coastal and Marine Protected Areas in India: Envis Bulletin Challenges and Way Forward 50 51 Wildlife and Protected Areas

Coastal And Marine Protected Areas In India: envis bulletin Challenges And Way Forward 50 51 Wildlife and Protected Areas Summary India has an extensive coastline of 7517 km length, of which 5423 km is in peninsular India and 2094 km is in the 02 2 Andaman & Nicobar and Lakshadweep islands. The EEZ has an extent of 2.02 million km . This coastline also supports a huge human population, which is dependent on the rich coastal and marine resources. Despite the tremendous ecological and economic importance and the existence of a policy and regulatory framework, India's coastal and marine ecosystems are under threat. Numerous direct and indirect pressures arising from different types of economic development and associated activities are having adverse impacts on the coastal and marine biodiversity across the country. The marine protected area network in India has been used as a tool to manage natural marine resources for biodiversity conservation and for the well-being of people dependent on it. Scientific monitoring and traditional observations confirm that depleted natural marine resources are getting restored and/or pristine ecological conditions have been sustained in well managed MPAs. There are 24 MPAs in peninsular India and more than 100 MPAs in the country's islands. The 24 MPAs of the mainland have a total area of about 8214 km2, which is about 5% of the total protected area network of India and represents 0.25% of the total geographic area of the country. Dedicated efforts are required to secure and strengthen community participation in managing the marine protected area network in India. -

District Statistical Handbook. 2010-11 Andaman & Nicobar.Pdf

lR;eso t;rs v.Meku rFkk fudksckj }hilewg ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS Published by : Directorate of Economics & Statistics ftyk lkaf[;dh; iqfLrdk Andaman & Nicobar Administration DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK Port Blair 2010-11 vkfFZkd ,oa lkaf[;dh funs'kky; v.Meku rFkk fudksckj iz'kklu iksVZ Cys;j DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ADMINISTRATION Printed by the Manager, Govt. Press, Port Blair PORT BLAIR çLrkouk PREFACE ftyk lkaf[;dh; iqfLrdk] 2010&2011 orZeku laLdj.k The present edition of District Statistical Hand Øe esa lksygok¡ gS A bl laLdj.k esa ftyk ds fofHkUu {ks=ksa ls Book, 2010-11 is the sixteenth in the series. It presents lacaf/kr egÙoiw.kZ lkaf[;dh; lwpukvksa dks ljy rjhds ls izLrqr important Statistical Information relating to the three Districts of Andaman & Nicobar Islands in a handy form. fd;k x;k gS A The Directorate acknowledges with gratitude the funs'kky; bl iqfLrdk ds fy, fofHkUu ljdkjh foHkkxksa@ co-operation extended by various Government dk;kZy;ksa rFkk vU; ,stsfUl;ksa }kjk miyC/k djk, x, Departments/Agencies in making available the statistical lkaf[;dh; vkWadM+ksa ds fy, muds izfr viuk vkHkkj izdV djrk data presented in this publication. gS A The publication is the result of hard work put in by Shri Martin Ekka, Shri M.P. Muthappa and Smti. D. ;g izdk'ku Jh ch- e¨gu] lkaf[;dh; vf/kdkjh ds Susaiammal, Senior Investigators, under the guidance of ekxZn'kZu rFkk fuxjkuh esa Jh ekfVZu ,Ddk] Jh ,e- ih- eqÉIik Shri B. Mohan, Statistical Officer. -

Of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 233 of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal D.R.K. SASTRY ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 233 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Echinodermata of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal : An Annotated List D.R.K. SASTRY Zoo!ogicai Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Station, Port Blair-744 102 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Sastry, D.R.K. 2005. Echinodermata of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal: An Annotated List, Rec. zoo/. Surv. India, Occ. Paper No. 233 : 1-207. (Published : Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published : March, 2005 ISBN 81-8171-063-0 © Govt. of India, 2005 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in an form of binding or cover other than that in which, it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE Indian : Rs. 350.00 Foreign : $ 25; £ 20 Published at the Publication Division by the Director Zoological Survey of India, 234/4, AJe Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building, 13th floor, Nizam Palace, Kolkata 700020 and Printed at Shiva Offset Press, Dehra Dun-248 001.