Summary Report Fire Protection Master Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fire Management Lessons Learned – Evolving Fire Management Programs 1

Fire Management Lessons Learned Evolving Fire Management Programs on the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests of Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky and Sequoia National Forest and Giant Sequoia National Monument of California Prepared for U.S. Forest Service Washington Office and Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center By Carol Ewell and David Kerr, with contributions by Scott Williams – Adaptive Management Services Enterprise Team (AMSET) and Frankie Romero and Tim Sexton – U.S. Forest Service November 2013 Fire Management Lessons Learned – Evolving Fire Management Programs 1 Contents Executive Summary…………………………………….………... 3 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 2. George Washington and Jefferson National Forests……………………………………… 7 Theme 1: Organizational Culture……………………………………………………………… 7 Theme 2: Safety……………………………………………………………………………………..… 19 Theme 3: Economics……………………………………………………………………………..…. 21 Theme 4: Natural Resource Effects and Data Modeling…………………….…….. 22 3. Sequoia National Forest and Giant Sequoia National Monument…………..……… 29 Theme 1: Organizational Culture……………………………………………………………… 29 Theme 2: Safety………………………………………………………………………………..……… 40 Theme 3: Economics…………………………………………………………………………..……. 40 Theme 4: Natural Resource Effects and Data Modeling………………………..….. 43 4. National Goals Tie Ecosystem Restoration Together with Fire and Fuel Management…………………………………………………………..………. 47 5. Lessons Learned…………………………………………………………………………………..……….. 48 6. Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………..…….……. 51 7. References……………………………………………………………………………………………..……. -

Lion Fire Fuels Report

2015 Rough Fire Sierra and Sequoia National Forests and Kings Canyon National Park Fire Behavior Assessment Team Summary Report Pre-fire Plot 14 (Transect 2) Prepared by: Fire Behavior Assessment Team (FBAT), Adaptive Management Services Enterprise Team (AMSET) And USFS Wildland Firefighters & Technical Specialists Carol Ewell (AMSET), Science Lead, Mark Courson and Nick Jeros (PSW Region and Monongahela NF), Fire Operational Leads, Fire entering Plot 14 from down/side canyon Alicia Reiner, Chelsea Morgan (AMSET), Katherine Napier (Colville NF), Matthew Dickinson, Nicholas Skowronski, and Michael Gallagher (Northern Research Station), Robert Kremens (RIT University collaborator) Nicole Vaillant (PNW Research Station), and Summit Wildland Fire Module (Stanislaus NF) Jan. 13, 2015 (draft) Post-fire Plot 14 (Transect 2) Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 3 Approach/Methods ....................................................................................................................... 4 Vegetation and Fuel Measurements ........................................................................................ 5 Overstory Vegetation -

2018 Strategic Fire Plan

SShhaassttaa--TTrriinniittyy UUnniitt 22001188 SSTTRRAATTEEGGIICC FFIIRREE PPLLAANN UNIT STRATEGIC FIRE PLAN AMENDMENTS Page Numbers Description of Updated Date Section Updated Updated Update By 12/22/12 Appendix A Update to Projects DW 12/22/12 Appendix B Update Goals and Objectives DW 12/22/12 Appendix C Added Communities at risk DW 12/22/12 Appendix D Update Maps DW 4/5/14 Section Il Update Collaborators DW 4/5/14 Section Ill Update Values and Communities DW 4/5/14 Section V Added Camp, LaTour DW 4/5/14 Appendix A Update Project List DW 4/5/14 Appendix C Add Ignition Analysis DW 4/5/14 2013 Supplemental Add 2013 Supplement DW 4/09/15 Appendix C Updated Ignition Analysis DB 4/23/15 Appendix A Updated CalMAPPER Chart DB 4/09/16 Appendix A 40 Updated CalMAPPER Chart DB 4/09/16 New Plan Template 1-50 Utilized New Blank template DB 4/17/16 Appendix C 42 Updated Ignition Analysis DB 4/17/16 2015 Supplemental 50 Unit Accomplishments Page DB 2/1/17 Section V Update Battalion JWB 2/9/17 Appendix C 42 Updated Ignition Analysis JWB 2/15/17 Appendix A 39 Updated Project List JWB 3/2/17 2016 Supplemental 49 Unit Accomplishments Page JWB 3/28/17 All Sections 1-48 Update Fire Plan Doc JWB 2/5/18 All Sections Updated Document Format NW 2/5/18 Section 2 10 Update Communities at Risk NW 4/10/18 Section 2 9 Update Collaborators NW 2/6/18 Appendix B 38 Update Ignition Analysis NW 3/6/18 Appendix B 37 Update Goals and Objective NW 4/10/18 Appendix A 36 Updated Unit Project List NW 4/25/18 Section V 34 Updated LaTour Information NW 5/1/18 Cover New Cover Page NW 5/2/18 2017 Supplemental 48 Update Unit Accomplishments NW i Last update:May 10, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................. -

2018 Firefighters Memorial Honorees

2018 Firefighters Memorial Honorees: Jeffrey Alan Worsham - Whitesville Rural Fire Department - LODD Jack C. Amick - Columbia Fire Department Matthew Preston Baugus - New Holland Volunteer Fire Department Joe Dean Bell - CKC Fire Department Harry Francis Bennett - Yemassee Volunteer Fire Department Mark Wheeler Bowers - Prosperity Volunteer Fire Department Charles William Bowie, Sr. - City of Abbeville Fire Department Henry Plowden Bozard - Clarendon County Fire Department Richard G. Branham - Columbia Fire Department Robert Shaw Brannon - City of Goose Creek Fire Department Matthew Mitchell Brantly - Antreville Fire Deparmtent Raymond W Bryant - Anderson City Fire Department Buddy Randolph Carter - City of Charleston Fire Department Peter Christopher Carver - Elloree Fire Department Ercole P. Chiola - Sullivan's Island Fire Department Oscar Keys Clamp Jr. - Zion Fire Department George William Clemmons - Manning Fire Department Darrell Crawford Cole - Townville Fire Department Thomas Leon Devinney - Rock Hill Fire Department Amy Danielle Dimmery - Marion Rural Fire Department Lawrence M. Dukes, Jr. - Branchville Fire Department George Robert Ferguson - Bethel Fire Department Chad Victor Funchess - West Middle Volunteer Fire Department Brian Alexander Gaines - Grove Fire Department Ernest Wilton Gentry Jr. - Iva Fire Department Bill Gibson, Jr. - McColl Fire Department Oscar Wendell Grainger - Dillion County Fire Department Station 3 Turner Augustus Green - City of Sumter Fire Department Jerry Russell Greene - Rock Hill Fire Department -

Shasta Trinity Unit Headquarters / Northern Operations

STATE OF CALIFORNIA Capital Outlay Budget Change Proposal (COBCP) - Cover Sheet DF-151 (REV 07/20) Fiscal Year Business Unit Department Priority No. 2021-2022 3540 Department of Forestry Click or tap here to enter text. and Fire Protection Budget Request Name Capital Outlay Program ID Capital Outlay Project ID 3540-135-COBCP-MR 2485 0000971 Project Title Shasta Trinity Unit Headquarters / Northern Operations: Relocate Facility Project Status and Type Status: ☐ New ☒ Continuing Type: ☒Major ☐ Minor Project Category (Select one) ☐CRI ☐WSD ☐ECP ☐SM (Critical Infrastructure) (Workload Space Deficiencies) (Enrollment Caseload Population) (Seismic) ☒FLS ☐FM ☐PAR ☐RC (Fire Life Safety) (Facility Modernization) (Public Access Recreation) (Resource Conservation) Total Request (in thousands) Phase(s) to be Funded Total Project Cost (in thousands) $ 360 Preliminary plans $ 109,759 Budget Request Summary The Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) requests an additional $360,000 General Fund for the preliminary plans phase of the Shasta Trinity Unit Headquarters / Northern Operations: Relocate Facility project. CAL FIRE submitted a proposal for the preliminary plans phase of this project in the 2021-22 Governor’s Budget. This request amends the previous proposal to address scope and cost changes to the project. The total estimated project costs are now $109,759,000. Requires Legislation Code Section(s) to be Added/Amended/Repealed CCCI Click or tap here to enter text. ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. Requires Provisional Language Budget Package Status ☐ Yes ☒ No ☐ Needed ☐ Not Needed ☒ Existing Impact on Support Budget One-Time Costs ☒ Yes ☐ No Swing Space Needed ☐ Yes ☐ No Future Savings ☒ Yes ☐ No Generate Surplus Property ☐ Yes ☐ No Future Costs ☐ Yes ☒ No If proposal affects another department, does other department concur with proposal? ☒ Yes ☐ No Attach comments of affected department, signed and dated by the department director or designee. -

Political Subdivision/Emergency Service Entity 11/15/2017 1

Signature Authorized Official State Agency/County/Municipality/ Date Political Subdivision/Emergency Service Entity 11/15/2017 David M. Garner, County Director Abbeville County 10/25/2017 H. Neal Dickenson, Chief Abbeville City Fire/Rescue 11/17/2017 James W. Wilson, Chief Antreville Fire Department 11/17/2017 James W. Wilson, Chief McGill Fire Department 12/12/2017 Roy McClain, Fire Chief Due West Fire and Rescue 12/10/2020 Darrell Manning, Fire Chief Town of Calhoun Falls Fire Department 9/7/2017 J. Clay Killian, County Administrator Aiken County 10/11/2017 Gregg Cato, Vice President Midland Valley Fire Department *Bath Volunteer Fire Department *Clearwater Sewer & Fire Department 10/12/2017 Chad Hyler, Chief Belvedere Fire Department 10/12/2017 Gabriel Kitchings, Assistant Chief G.V.W. Fire Department 10/12/2017 Leon A. Henderson, Assistant Chief Beech Island Fire Department 10/12/2017 Van E. Willing, Assistant Chief Center Fire Department 10/12/2017 Nathan Shuler, Chief Monetta Volunteer Fire Department 10/12/2017 Mike Kellems, Fire Chief New Ellenton Fire Department 10/12/2017 Nathan Shuler, Chief Monetta Volunteer Fire Department 10/20/2017 George A. Laiacona, III, Chief Couchton Fire and Rescue 10/24/2017 Glenn L. Poole, Chief Hollow Creek Fire Department 10/25/2017 Jeremy Thorne, Fire Chief Jackson Fire Department 10/31/2017 Dennis L. Jackson, Chief New Holland Fire Department 11/10/2017 J.E. Fogle, Chief Salley Fire Department 11/15/2017 Robert Verbockel, Assistant Chief Montmorenci Volunteer Fire Department 12/15/2017 Joseph T. Wood, Chief Eureka Volunteer Fire Department 2/22/2018 John C. -

2019-2020 Shasta County Grand Jury - Final Report

2019-2020 Shasta County Grand Jury - Final Report Grand Jury Report -1- July 1, 2020 Shasta County Grand Jury 2019-2020 Shasta County Grand Jury 2019-2020 July 1, 2020 Honorable Daniel E. Flynn Presiding Judge of the Superior Court 1500 Court Street Redding CA. 96001 Richard Buchner Will Arthur 1 Trevor Allen 1 1 Jonessa Brittan 1 1Grand Jury Foreperson 1 1Foreperson Pro Tem 1 Dear Judge Flynn, The 2019-2020 Shasta County Grand Jury respectfully submits its final report. Grand Jury operation and success is a remarkable team effort with everyone “stepping up to the plate” to help. Our jury thanks you and your staff for your direction, guidance and reviews. Through challenging times, Senior County Counsel Mathew McOmber gets a huge thank you for his legal counsel and thorough review of our reports. Thank you to Chief Deputy District Attorney Benjamin Hanna for his legal counsel when needed. Jenn Duval and her staff at County Admin- istration were always there to help and guide us through the operational side of the Grand Jury function. Computer support is critical for Grand Jury success. Michael Stock and his staff worked with our information technology officer to provide very good computer support for which we are thankful. 1 1 Bob Cathaway 1 1 Greg Ephland 1 1 Sharon Heisley 1 1 Richard Jacobsen 1 1 Andrew Johnson 1 Grand Jurors accomplished a remarkable amount of work in a very short amount of time. This would not have been possible without the training, help and support of the California Grand Jury Association and their dedicated professionals. -

015-2018 SHMP FINAL Appendices

APPENDICES – 2018 STATE HAZARD MITIGATION TEAM ROSTER OF AGENCIES AND STAKEHOLDER ORGANIZATIONS AECOM National Governments Alameda County Office of Emergency Services Alpine County Operational Area Inland Region IV Air Resources Control Board (ARB) Amador County Operational Area Inland Region IV American Planning Association California Chapter American Red Cross (Sacramento Chapter) Association of Bay Area Governments Association of Contingency Planners Association of Environmental Professionals Burbank Fire Corps Business and Industry Council for Emergency Planning & Preparedness (BICEPP) Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency Business Executives for National Security (BENS) Business Recovery Managers Association Butte County Operational Area Inland Region III California Adaptation Forum California Association of Councils of Governments Cahuilla Band of Indians California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection Calaveras Council of Governments California Coastal Commission California Conservation Corps California Community Colleges California Department of Community Services and Development California Department of Conservation California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation California Department of Education California Department of Food and Agriculture California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE) California Department of General Services California Department of Housing and Community Development California Department of Insurance California Department of Public Health California Department of Public -

Safeguard Properties Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide

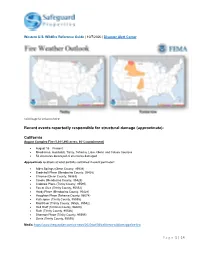

Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 10/7/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Click image for enhanced view Recent events reportedly responsible for structural damage (approximate): California August Complex Fire (1,011,493 acres; 60% containment) August 16 – Present Mendocino, Humboldt, Trinity, Tehama, Lake, Glenn and Colusa Counties 52 structures destroyed; 6 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Alder Springs (Glenn County, 95939) Bredehoft Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Chrome (Glenn County, 95963) Covelo (Mendocino County, 95428) Crabtree Place (Trinity County, 95595) Forest Glen (Trinity County, 95552) Hardy Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Houghton Place (Tehama County, 96074) Kettenpom (Trinity County, 95595) Mad River (Trinity County, 95526, 95552) Red Bluff (Tehama County, 96080) Ruth (Trinity County, 95526) Shannon Place (Trinity County, 95595) Zenia (Trinity County, 95595) Media: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/oct/06/california-wildfires-gigafire-first P a g e 1 | 14 Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 10/7/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Bobcat Fire (115,796 acres; 89% containment) September 6 – Present Los Angeles County *Northeast of Cogswell Reservoir, San Gabriel Canyon 163 structures destroyed; 47 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Big Rock Springs (Los Angeles County, 93544) Hidden Springs (Los Angeles County, 93550) Juniper Hills (Los Angeles County, 93543, 93553)) Littlerock (Los -

Grant Awards List

19-20 AWARD COMPANY NAME COUNTY ORG TYPE GRANT AMOUNT Alpha Fire Company No. 1 Adams Fire Yes $ 25,205 Arendtsville Community Fire Company Adams Fire Yes $ 24,794 Barlow Volunteer Fire Department Adams Fire Yes $ 23,562 Bendervile Community Fire Co Adams Fire Yes $ 24,384 Biglerville Hose & Truck Co#1 Adams Fire Yes $ 23,973 Buchanan Valley Volunteer Fire Department, Inc Adams Fire Yes $ 25,342 Cashtown Community Fire Dept. Adams Fire Yes $ 24,247 Eagle Fire Company No. 2 Adams Fire Yes $ 24,794 Fairfield Community Fire Co. Adams Fire Yes $ 24,247 Fountain Dale Volunteer Fire Department Adams Fire Yes $ 25,205 Gettysburg Fire Department Inc Adams Fire Yes $ 25,342 Greenmount Community Fire Company Adams Fire No $ 11,094 Hanover Borough Fire Department Adams Fire Yes $ 24,931 Heidlersburg Fire Company Adams Fire Yes $ 23,288 Irishtown Fire Company Adams Fire Yes $ 23,562 Northeast Adams Fire & EMS Adams Fire Yes $ 35,473 Penn Township Department of Fire & Rescue Services Adams Fire Yes $ 24,794 Southeastern Adams Volunteer Emergency Services Inc Adams Fire Yes $ 25,068 United Hook & Ladder Company #33 Adams Fire Yes $ 36,842 York Springs Fire Company Adams Fire No $ 11,094 Adams Regional Emergency Medical Services Inc ADAMS EMS YES $ 15,048 Biglerville Hose & Truck Co#1 EMS ADAMS EMS YES $ 15,048 York Springs Fire Co #1 ADAMS EMS YES $ 12,517 Aleppo Township Volunteer Fire Co., Inc. Allegheny Fire Yes $ 23,288 Allegheny Valley Volunteer Fire Company #1 Allegheny Fire Yes $ 34,651 Ambridge Borough Fire Department Allegheny Fire Yes $ 23,288 Aspinwall Volunteer Fire Department Inc Allegheny Fire Yes $ 23,973 Avalon Volunteer Fire Company Allegheny Fire Yes $ 23,151 Baldwin Emergency Medical Services Inc Allegheny Rescue Yes $ 23,973 Baldwin Independent Fire Co. -

A Conservation Strategy for the Black-Backed Woodpecker (Picoides Arcticus) in California – Version 2.0

A Conservation Strategy for the Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) in California – Version 2.0 Male Black-backed Woodpecker foraging, Lassen National Forest. Photo by Joseph Leibrecht Edited by Rodney B. Siegel1, Monica L. Bond2, Christine A. Howell3, Sarah C. Sawyer3, and Diana L. Craig3 1The Institute for Bird Populations 2Wild Nature Institute 3USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region February 5, 2018 The Institute for Bird Populations A Conservation Strategy for the Black-backed Woodpecker in California v2.0 Recommended Citation: Siegel, R. B., M. L. Bond, C. A. Howell, Sarah C. Sawyer, and, D. L. Craig, editors. 2018. A Conservation Strategy for the Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) in California. Version 2.0. The Institute for Bird Populations and California Partners in Flight. Point Reyes Station, California. The Institute for Bird Populations A Conservation Strategy for the Black-backed Woodpecker in California v2.0 Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 About Version 2.0.......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Recommended Conservation Actions ......................................................................................... 8 Species Description .................................................................................................................... -

Saylor Creek Herd Management Area Wild Horse Gather Plan Environmental Assessment

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management DOI-BLM-ID-T010-2019-0006-EA Final Saylor Creek Herd Management Area Wild Horse Gather Plan Environmental Assessment U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Twin Falls District Jarbidge Field Office 2878 Addison Ave E. Twin Falls, ID 83301 Phone: (208) 736-2350 FAX: (208) 736-2375 1.0 Purpose and Need for Action ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Purpose and Need for Action .............................................................................................................. 1 1.4 Decision to be Made ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.5 Conformance with Applicable Land Use Plan ................................................................................... 1 1.6 Relationship to Statutes, Regulations or Other Plans ......................................................................... 1 1.7 Scoping, Public Involvement, and Issues ........................................................................................... 2 2.0 Description of the Alternatives ...........................................................................................................