Fellowships for Individual Artists 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giving Report 2019-2020

Giving Report F I R M FOUNDATIONS 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Mission 3 Letter from the President The mission of Bishop Kelley High School is to carry on the teaching ministry of Jesus Christ by providing a Catholic, Lasallian Board of Directors & education that develops individuals whose hearts and minds are prepared for a purposeful life. 4 PhilanthropyTeam 5 Letter from Bishop Konderla Our Core Values 6 Gifts to Believe in Kelley Faith in the Presence of God 9 National Merit & AP Scholars We call each other into a deeper awareness of our saving relationship with a caring and loving God through Jesus Christ. Let us remember we are in the Holy Presence of God. A Firm Foundation: 10 Celebrating Br. Alfred Concern for the Poor and Social Justice 11 Lasallian Founders Awards We call each other to an awareness to the poor and victims of injustice and respond through community service and advocacy. Enter to Learn, Leave to Serve. 12 Consecutive Years of Giving 15 Trivia Night Respect for All Persons We acknowledge each other’s dignity and identity as children of God. 16 Financial Profile Live Jesus in our hearts... forever. 18 Legacy Society Quality Education 20 Angelo Prassa Golf Tournament We provide an education that prepares students not only for college, career and vocation, but also for life through the Lasallian ideal. Teaching Minds and Touching Hearts. 20 BK Adds 7 Acres 21 Gifts to Athletics Inclusive Community 22 RCIA We are a Catholic community where diverse strengths and limitations are recognized and accepted. The Lasallian Family 22 Miscellaneous Funds 23 GO for Catholic Schools Our Vision Form Disciples | Educate for Life | Leave to Serve Speech and Debate 24 Goes to Nationals Bishop Kelley High School forms disciples of Jesus Christ in the tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. -

Visit-Milwaukee-Map-2018.Pdf

19 SHERIDAN’S BOUTIQUE HOTEL & CAFÉ J7 38 HISTORIC MILWAUKEE, INC. C3 57 77 97 MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MARKET C3 117 WATER STREET BREWERY C2 ACCOMMODATIONS BLU C3 FUEL CAFÉ D1 135 MILWAUKEE HARLEY-DAVIDSON I6 5133 S. Lake Dr., Cudahy 235 E. Michigan St., Milwaukee 424 E. Wisconsin Ave., Milwaukee 818 E. Center St., Milwaukee 400 N. Water St., Milwaukee 1101 N. Water St., Milwaukee 11310 W. Silver Spring Rd., Milwaukee (414) 747-9810 | sheridanhouseandcafe.com (414) 277-7795 | historicmilwaukee.org (414) 298-3196 | blumilwaukee.com (414) 372-3835 | fuelcafe.com (414) 336-1111 | milwaukeepublicmarket.org (414) 272-1195 | waterstreetbrewery.com (414) 461-4444 | milwaukeeharley.com 1 ALOFT MILWAUKEE DOWNTOWN C2 Well appointed, uniquely styled guest rooms Offering architectural walking tours through Savor spectacular views from the top of the Pfi ster Hotel Fuel offers killer coffee and espresso drinks, great Visit Milwaukee’s most unique food destination! In the heart of the entertainment district, Visit Milwaukee Harley, a pristine 36K sq ft 1230 N. Old World 3rd St., Milwaukee with high end furnishings. Seasonal menu, casual downtown Milwaukee and its historic neighborhoods. while enjoying a fi ne wine or a signature cocktail. sandwiches, paninis, burritos, and more. Awesome A year-round indoor market featuring a bounty of Milwaukee’s fi rst brew pub serves a variety of showroom fi lled with American Iron. Take home (414) 226-0122 | aloftmilwaukeedowntown.com gourmet fare. Near downtown and Mitchell Int’l. Special events and private tours available. t-shirts and stickers. It’s a classic! the freshest and most delicious products. award-winning craft brews served from tank to tap. -

Artist's Proposal

Gabbert Artist’s Proposal 14th Street Roundabout Page 434 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor Ladies and Gentlemen, Thank you for this opportunity. For your consideration I propose a work tentatively titled “Flame”. I believe it to be simple-yet- compelling, symbolic, and appropriate to this setting. Dimensions will be 20 feet high by 14.5 feet wide by 14.5 feet deep. It sits on a 3.5 feet high by 9 feet in diameter base. (not accurately dimensioned in the 3D graphics) The composition. The design has substance, and yet, there is practically no impediment to drivers’ visibility. After review of the design by a structural engineer the flame flicks may need to be pierced with openings to meet the 150 mph wind velocity requirement. I see no problem in adjusting the design to accommodate any change like this. Fire can represent our passions, zeal, creativity, and motivation. The “flame” can suggest the light held by the Statue of Liberty, the fire from Prometheus, the spirit of the city, and the hearth-fire of 612.207.8895 | jgsculpture.webs.com | [email protected] 14th Street Roundabout Page 435 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor home. It would be lit at night with a soft glow from within. A flame creates a sense of place because everyone is drawn to a fire. A flame sheds light and warmth. Reference my “Hopes and Dreams” in my work example to get a sense of what this would look like. The four circles suggest unity and wholeness, or, the circle of life, or, the earth/universe. -

Days & Hours for Social Distance Walking Visitor Guidelines Lynden

53 22 D 4 21 8 48 9 38 NORTH 41 3 C 33 34 E 32 46 47 24 45 26 28 14 52 37 12 25 11 19 7 36 20 10 35 2 PARKING 40 39 50 6 5 51 15 17 27 1 44 13 30 18 G 29 16 43 23 PARKING F GARDEN 31 EXIT ENTRANCE BROWN DEER ROAD Lynden Sculpture Garden Visitor Guidelines NO CLIMBING ON SCULPTURE 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. Do not climb on the sculptures. They are works of art, just as you would find in an indoor art Milwaukee, WI 53217 museum, and are subject to the same issues of deterioration – and they endure the vagaries of our harsh climate. Many of the works have already spent nearly half a century outdoors 414-446-8794 and are quite fragile. Please be gentle with our art. LAKES & POND There is no wading, swimming or fishing allowed in the lakes or pond. Please do not throw For virtual tours of the anything into these bodies of water. VEGETATION & WILDLIFE sculpture collection and Please do not pick our flowers, fruits, or grasses, or climb the trees. We want every visitor to be able to enjoy the same views you have experienced. Protect our wildlife: do not feed, temporary installations, chase or touch fish, ducks, geese, frogs, turtles or other wildlife. visit: lynden.tours WEATHER All visitors must come inside immediately if there is any sign of lightning. PETS Pets are not allowed in the Lynden Sculpture Garden except on designated dog days. -

Paper Abstracts

PAPER ABSTRACTS 43rd Annual Conference Thursday, April 7th –– Saturday, April 9th, 2016 DePaul University, Chicago rd The 43 Annual Conference of the Midwest Art History Society is sponsored by: DePaul University The Art Institute of Chicago Columbia College Loyola University Institutional Members of the Midwest Art History Society The Cleveland Museum of Art The Figge Art Museum The Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park Illinois State University School of Art The Krasl Art Center Michigan State University Art, Art History & Design The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Northern Arizona University Art Museum The Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame University of Illinois at Chicago School of Art & Art History University of Iowa Museum of Art University of Iowa School of Art and Art History The University of Kansas The Kress Foundation Department of Art History Wright State University Art Galleries 2 CONTENTS Conference at a Glance 5 Conference Schedule and Abstracts 7 Undergraduate Session (I) 7 El Arte in the Midwest 8 Asian Art 10 Chicago Design: Histories and Narratives 11 The Social Role of the Portrait 13 Latin American and Pre-Columbian Art 14 History of Photography 16 Black Arts Movement 18 The Personal is Political: Feminist Social Practice 18 International Art Collections of Chicago 20 The Chicago World’s Fair: A Reevaluation 21 Native American Images in Modern and Contemporary Art 22 Art for All Seasons: Art and Sculpture in Parks and Gardens 23 Open Session (I) 25 Architecture 26 Twentieth-Century Art (I) 28 Recent Acquisitions -

Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS for INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2018 the Greater Milwaukee Foundation’S Mary L

The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2018 The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2018 The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund FELLOWSHIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS 2018 Chris CORNELIUS Keith NELSON Nazlı DİNÇEL Makeal FLAMMINI Rosemary OLLISON June 7-August 4, 2019 Haggerty Museum of Art For more than a century, the Greater Milwaukee Foundation has helped individuals, families and organizations realize their philanthropic goals and make a difference in EDITOR’S PREFACE the community, during their lifetimes and for future generations. The Foundation consists of more than 1,300 individual charitable funds, each created by donors to serve the charitable causes of their choice. The Foundation also deploys both human and financial resources to address the most critical needs of the community and ensure the vitality of the region. Established in 1915, the Foundation was one of the first community foundations in the world and is now among the largest. In 2003, when the Greater Milwaukee Foundation decided to use a portion of a bequest from artist Mary L. Nohl The Greater Milwaukee Foundation to underwrite a fellowship program for individual visual artists, it made a major investment in local artists who 101 West Pleasant Street historically lacked access to support. The program, the Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund Milwaukee, WI 53212 Fellowships for Individual Artists, makes unrestricted awards to artists to create new work or complete work in Phone: (414) 272-5805 progress, and is open to practicing artists residing in Milwaukee, Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington counties. -

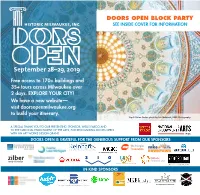

Doors Open Block Party See Inside Cover for Information

DOORS OPEN BLOCK PARTY SEE INSIDE COVER FOR INFORMATION Free access to 170+ buildings and 35+ tours across Milwaukee over 2 days. EXPLORE YOUR CITY! We have a new website— visit doorsopenmilwaukee.org to build your itinerary. Tripoli Shrine Center, photo by Jon Mattrisch, JMKE Photography A SPECIAL THANK YOU TO OUR PRESENTING SPONSOR, WELLS FARGO AND TO THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT OF THE ARTS, FOR RECOGNIZING DOORS OPEN WITH AN ART WORKS DESIGN GRANT. DOORS OPEN IS GRATEFUL FOR THE GENEROUS SUPPORT FROM OUR SPONSORS IN-KIND SPONSORS DOORS OPEN MILWAUKEE BLOCK PARTY & EVENT HEADQUARTERS East Michigan Street, between Water and Broadway (the E Michigan St bridge at the Milwaukee River is closed for construction) Saturday, September 28 and Sunday, September 29 PICK UP AN EVENT GUIDE ANY TIME BETWEEN 10 AM AND 5 PM BOTH DAYS ENJOY MUSIC WITH WMSE, FOOD VENDORS, AND ART ACTIVITIES FROM 11 AM TO 3 PM BOTH DAYS While you are at the block party, visit the Before I Die wall on Broadway just south of Michigan St. We invite the public to add their hopes and dreams to this art installation. Created by the artist Candy Chang, Before I Die is a global art project that invites people to contemplate mortality and share their personal aspirations in public. The Before I Die project reimagines how walls of our cities can help us grapple with death and meaning as a community. 2 VOLUNTEER Join hundreds of volunteers to help make this year’s Doors Open a success. Volunteers sign up for at least one, four-hour shift to help greet and count visitors at each featured Doors Open site throughout the weekend. -

March 9, 2021 Brenda Mallory Chair White House Council On

March 9, 2021 Brenda Mallory Chair White House Council on Environmental Quality 730 Jackson Pl NW Washington, DC 20506 Via email Re: Utility disconnection moratorium for Tennessee Valley Authority Dear Ms. Mallory, Please find attached petitions signed by over 21,500 people from Tennessee and beyond urging the Tennessee Valley Authority to institute a utility shutoff moratorium throughout its service area. As the letters attached state, “Without electricity, people won’t be able to shelter in homes that are a safe temperature, support remote schooling for their kids, or refrigerate their medicines. It is a decision that literally has life-or-death consequences.” For several months throughout the pandemic, advocates have urged TVA to institute such a moratorium, but to no avail. We now call upon President Biden to act, by issuing an Executive Order directing TVA to keep people’s power on-- the only responsible option during a pandemic. Please also find attached a memo outlining the President’s authority to issue an Executive Order to this effect. Sincerely, Tom Cormons Executive Director Appalachian Voices Erich Pica President Friends of the Earth Cc: Gina McCarthy, White House National Security Advisor Representative Peter DeFazio, Chair, House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure Senator Tom Carper, Chair, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Representative Frank Pallone, Chair, House Committee on Energy and Commerce Tennessee Congressional delegation Attachments: Executive Actions for Immediate COVID relief and economic recovery via the Tennessee Valley Authority, Appalachian Voices Appalachian Voices petition Appalachia Voices petition signatories Friends of the Earth petition Friends of the Earth petition signatories EXECUTIVE ACTIONS FOR IMMEDIATE COVID RELIEF AND ECONOMIC RECOVERY VIA THE TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY The Tennessee Valley Authority was established in the 1930s by a federal mandate to bring flood relief, economic stimulus and improved quality of life to the people of the Tennessee Valley. -

Photo by Martin Staples, Staples Photography Village REAL ESTATE

August 2019 Photo by Martin Staples, Staples Photography Village REAL ESTATE HOMES SOLD IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD Address Square Feet Beds Baths Sold Price 411 E Daphne Rd 4,238 5 3+2(.5) $1,283,500 8405 N Lake Dr 3,428 4 3.5 $985,000 1351 E Bywater Ln 4,200 5 4.5 $875,000 7946 N Fairchild Rd 5,504 4 4 $679,375 8017 N Links Way 4,738 4 2.5 $595,000 7861 N Fairchild Rd 3,292 3 2.5 $565,075 8214 N Whitney Rd 1,567 3 2 $291,000 7639 N Seneca Rd 1,934 3 2 $289,900 7530 N Crossway Rd 2,042 3 2 $284,900 8329 N Whitney Rd 1,390 3 2 $282,000 Best Version Media does not guarantee the accuracy of the statistical data on this page. The data does not represent the listings of any one agent or agency but represents the activity of the entire real estate community in the area. Any real estate agent’s ad appearing in the magazine is separate from the statistical data provided which is in no way a part of their advertisement. Up-sizing or downsizing, let me help you get to where you want to be: Fran Maglio Wallace Senior Executive Associate HOMEPut my 30 years of real estate 414.350.6358 [email protected]@firstweber.com experience to work for you. • Home values are at or near record highs FRANMAGLIOWALLACE.COM • Interest rates are low... for now • Inventory is tight and demand is high • We have buyers ready to move Let’s get you moving! 7330 N. -

Summer Art & Nature Camps

Summer Art & Nature 2015 CAMPS AT A GLANCE Camps Dates Time Camp Ages Summer June 15-17 9 am-4 pm Bird House 6-11 June 18-19 9 am-4 pm Across the Pond 6-11 Art & Join us for a summer of art and nature! June 22-24 9-11 am Trees, Toads & Treasures 20 mos.-4 June 22-24 1-4 pm Garden Animals 4-6 Lynden’s art and nature camps for children aged 20 months June 25-26 9 am-4 pm Grow Your Own 6-11 Nature to 13 years integrate our collection of monumental outdoor June 29-July 2 9 am-4 pm Art Elements 6-11 sculpture with the natural ecology of park, pond, and woodland. July 6-7 9 am-4 pm Spirals 6-11 Led by artists, naturalists, and art educators, the camps July 8-10 9 am-4 pm Tree House 6-11 Camps explore the intersection of art and nature through collaborative July 13-17 9 am-12 pm Movement & Migration 6-11 discovery and hands-on artmaking, using all of Lynden’s July 13-15 1-4 pm Sea & Sky 4-6 40 acres to create a joyful outdoor experience. Each camp July 20-24 9 am-12 pm Imaginary Creatures 7-11 concludes with an informal showing for family and friends. July 20-24 9 am-12 pm Flower World 6-8 July 20-24 1-4 pm Four Corners 6-11 July 27-31 9 am-4 pm Lost Civilization 6-11 REGISTRATION POLICIES August 3-7 9 am-4 pm Idea to Object 6-11 August 10-14 9 am-12 pm Into the Air 8-10 Enrollment is limited, please register early. -

Los Angeles: the First Biennium and Beyond

Music in Southern California: A Tale of Two Cities 51 RoBINSON, Al.FREO. Life in California: during a residence SPll::R, LESLIE. "Southern Diegueño Customs," Univer ofsevera/ years in the territory (New York: Wiley & sity of California Publications in American Ar Putnam, 1846). chaeology and Ethnology, xx (1928) Phoebe ScHWARTZ, HENRY . "Temple Beth Israel," JSDH, Apperson Hearst Memorial Volume. xxvu/4 (Fall 1981). TREUTLEIN, T11 EODORE E. "The Junípero Serra Song at SERRA, JUNIPERO. Writings, ed. Antonine Ti besar San Diego State Teachers College," JSDH, xxm/2 (Washington: Academy of American Franciscan (Spring 1977). History, 1955- 1966). 4 vols. VAN DYKE, T. S. The City and County of San Diego (San SILVA, ÜWEN FRANCIS DA, ed. Mission music of Califor Diego: Leberthon & Taylor, 1888). nia, a col/ection oj old Ca/ifornia mission hymns WATERMAN, T. T. "The Religious Practices of thc Die and masses (Los Angeles: W. F. Lewis, 1941). gueño lndians," University of California Publica S1MONSON, HAROLD P. "The Villa Montezuma: Jesse tions in American Archaeology and Ethnology, Shepard's Lasting Contribution to the Arts and Ar vm/ 6 (1910). chitecture," JSDH, xix/2 (Spring 1973). WEBER, FRANcis, comp. and ed. The Proto Mission, A "Sorne of the Prominent Composers Residing in the Documentary History of San Diego de Alca/a (Hong West," Pacific Coast Musician, xx1v/6 (February Kong: Libra Press, 1979). 16, 1935). Los Angeles: The First Biennium and Beyond Encyclopedia Coverage IN 1960, Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, encapsulating his prime source book, Howard vm, 1213-1217, pioneered with a city article on Los Swan's Music in the Southwest, /825- 1950. -

2018 Camps at a Glance

2018 CAMPS AT A GLANCE Dates Time Camp Ages June 11-15 9 am-4 pm Fields of View 6-11 June 18-22 9 am-4 pm Pond Metropolis 6-11 June 25-27 9-11 am Flower Garden 20 mos.-4 June 25-27 9 am-4 pm Whittlers 10-15 SUMMER CAMPS July 9-13 9 am-1:30 pm Writers in the Garden 10-15 July 16-20 9 am-4 pm Pond Voyage 6-11 AT THE INTERSECTION July 30-August 1 9 am-12 pm Hara’s Home 4-6 July 30-August 3 1-4 pm Symbiotic Relationships 10-15 August 6-10 9 am-4 pm Four Corners 6-11 OF ART AND NATURE August 13-15 9-11 am Roots & Feet 20 mos.-4 August 13-15 9 am-12 pm Story River 4-6 SUMMER CAMPS August 20-24 9-11:30 am Les Artistes 5-7 Lynden’s art and nature camps for children aged 20 months AT THE INTERSECTION to 15 years integrate our collection of monumental outdoor sculpture with the natural ecology of our hidden landscapes REGISTRATION POLICIES and unique habitats. Led by artists, naturalists, and art OF ART AND NATURE educators, the camps explore the intersection of art and nature Enrollment is limited, please register early. Camps are filled on a first-come, first-served basis. through collaborative inquiry and hands-on artmaking, using June 11-August 24, 2018 all of Lynden’s 40 acres to create a joyful, all-senses-engaged Cancellation outdoor experience. Most camps conclude with an informal If a camp is filled to capacity, or cancelled due to low enrollment showing for family and friends.