F All 201 6 Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GORDON RAMSAY's POLITENESS STRATEGIES in MASTERCHEF and MASTERCHEF JUNIOR US Annisa Friska Safa Eri Kurniawan Departemen Bahas

Annisa Friska Safa & Eri Kurniawan, Gordon Ramsay’s Politeness Strategies GORDON RAMSAY’S POLITENESS STRATEGIES IN MASTERCHEF AND MASTERCHEF JUNIOR US Annisa Friska Safa Eri Kurniawan Departemen Bahasa dan Sastra Inggris FPBS UPI Address: Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi 229 Bandung 40154 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This research aims to investigate the types of politeness strategies that are performed by Gordon Ramsay in judging the Masterchef US and Masterchef Junior US contestants’ dishes and to reveal whether Gordon Ramsay performs any different politeness strategies between the Master chef and Masterchef Junior contestants. The data spring from Gordon Ramsay utterances, taken from the elimination test of two episodes of Masterchef season 4 (episode 9 and 12) and the elimination test of two episodes of Masterchef Junior US season 1 (episode 2 and 6). The framework of Brown & Levinson’s (1987) politeness strategies is adopted. Findings reveal that Gordon Ramsay performed bald on-record strategy, positive politeness, and off record strategy. Furthermore, Ramsay performed diferent varieties of politeness strategies in Masterchef; and performed only positive politeness strategy in Masterchef Junior. Keywords: politeness strategies, masterchef, masterchef junior, Gordon Ramsay Abstrak Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk menyelidiki tipe strategi kesopanan yang dilakukan oleh Gordon Ramsay saat menilai masakan dari kontestan Masterchefdan Masterchef Junior US dan untuk mengungkapkan adakah perbedaan strategi kesopanan yang dilakukan Gordon Ramsay kepada kontestan Masterchef US dan Masterchef Junior US. Data penelitian ini berupa tuturan Gordon Ramsay yang diambil dari tes eliminasi dalam dua episode Masterchef US musim ke-4 (episode 9 dan 12), dan dua episode Masterchef Junior US musim pertama (episode 2 dan 6). -

France's Banijay Group Buys Endemol Shine to Create European Production Giant

Publication date: 28 Oct 2019 Author: Tim Westcott Director, Research and Analysis, Programming France's Banijay Group buys Endemol Shine to create European production giant Brought to you by Informa Tech France's Banijay Group buys Endemol Shine to 1 create European production giant France-based production company Banijay Group has reached agreement to acquire Endemol Shine Group from Walt Disney Company and US hedge fund Apollo Global Management. The price for the deal was not disclosed but is widely reported to be $2.2 billion. A statement from the group said the deal will be financed through a capital increase of Banijay Group and debt. On closure, subject to regulatory clearances and employee consultations. Post-closing, the combined group will be majority owned (67.1%) by LDH, the holding company controlled by Stephane Courbit's LOV Group, and Vivendi (32.9%), which invested in Banijay in 2014. The merged group said it will own almost 200 production companies in 23 territories and the rights for close to 100,000 hours of content, adding that total pro-forma revenue of the combined group is expected to be €3 billion ($3.3 billion) this year. Endemol Shine Group is jointly owned by Disney, which acquired its 50% stake as part of its acquisition of 21st Century Fox last year, and funds managed by affiliates of Apollo Global Management. Endemol Shine has 120 production labels and owns 66,000 hours of scripted and non- scripted programming and over 4,300 registered formats. Our analysis Endemol Shine Group has been up for sale since last year, and Banijay Group appears to be have been the only potential buyer to have made an offer, despite reported interest from All3Media, RTL Group-owned Fremantle and others. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

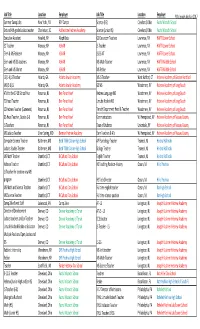

All Positions.Xlsx

Job Title Location Employer Job Title Location Employer YU's Jewish Job Fair 2017 Summer Camp Jobs New York , NY 92Y Camps Science (HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School 3rd and 4th grade Judaics teacher Charleston, SC Addlestone Hebrew Academy Science (Junior HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School Executive Assistant Hewlett, NY Aleph Beta GS Classroom Teachers Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School EC Teacher Monsey, NY ASHAR JS Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem & MS Rebbeim Monsey, NY ASHAR JS/GS AT Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem and MS GS teachers Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Math Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School Elem and MS Morot Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Rebbe Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School LS (1‐4) JS Teacher Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy MS JS Teacher‐ West Hatford, CT Hebrew Academy of Greater Hartford MS (5‐8) JS Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy GS MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach ATs for the 17‐18 School Year Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Hebrew Language MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Head Teacher Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Limudei Kodesh MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Hebrew Teacher (Ganenent) Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Tanach Department Head & Teacher Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach GS Head Teacher, Grades 1‐8 Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Communications W. Hempstead, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County JS Teachers Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Dean of Students Uniondale, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County MS Judaics Teacher Silver Spring, MD Berman Hebrew Academy Elem Teachers & ATs W. -

2018 Fellow Bios

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2018 Fellow Bios Jonathan Arking is a junior at Beth Tfiloh High school. There, he captains the Model UN and cross- country teams and serves as the head of the school's AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) club. In addition, he participates in Mock Trial, NHS, Kolenu (the high school choir), and the ultimate Frisbee team. Outside of school, Jonathan frequently reads the Torah portion and leads the services at Congregation Netivot Shalom, the Modern Orthodox synagogue he and his family founded, and now attend. In his free time, Jonathan loves running, reading, and singing -- especially traditional Jewish songs. He is greatly excited to be a Bronfman Fellow and looks forward to an inspiring and insightful summer. Hannah Bashkow is currently a junior at Tandem Friends School. Before that, she attended the Charlottesville Waldorf School through eighth grade. She and her family are members of Charlottesville’s Congregation Beth Israel, where they regularly attend the Saturday morning traditional egalitarian minyan. At the synagogue, she works as a Hebrew tutor and helps kids prepare for their b’nei mitzvah. She is an enthusiastic artist who enjoys working in many media. In past summers, she has attended Nature Camp, a local field ecology camp, and has traveled with her family to Israel, Europe, and Papua New Guinea. Sarah Bock is a junior at Scarsdale High School and a member of Westchester Reform Temple. At SHS, Sarah is a member of Signifer, which functions as Scarsdale’s Honor Society, as well as a peer tutoring program. She is on the school’s cross country and track teams and is a member of the Pratham club, which raises money to fund women’s education in India. -

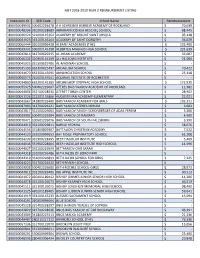

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Annual Report 2015

Annual Report 2015 - 2016 From the President and Executive Director Describing the condition of world Jewry in the aftermath of World War II, the twentieth century theologian Eliezer Berkovits observed that the Jewish people stood “between yesterday and tomorrow.” On the one hand, “yesterday” was no more. On the other hand, the future was unclear; “tomorrow” had not yet dawned. BJE shapes the present of Jewish education in Los Angeles - with the support of institutional and individual partners - by drawing from the rich wisdom of yesterday, helping learners experience a meaningful present and contribute to a better tomorrow. Through engaging children and families in Jewish education, enhancing the quality of Jewish education and expanding access to Jewish learning opportunities, BJE helps build today’s Jewish educational experiences, enabling successive generations to create a more robust tomorrow. The pages of this Annual Report share several aspects of this work. From early childhood education, to Dr. Alan M. Spiwak innovative approaches at (complementary) religious schools; from multiple generations experiencing and reflecting on “March of the Living” to college students engaging with issues in Jewish education and communal service as BJE Lainer Interns; from initiatives to help families access Jewish day school education to programs that strengthen the teaching of Hebrew, BJE is, with your help, building the present and shaping the future. Thank you for your partnership as a builder of Jewish education. With best wishes in 2016-2017 (5777). Sincerely, Dr. Alan M. Spiwak Dr. Gil Graff President Executive Director Dr. Gil Graff BJE 2015-2016 Board of Directors Table of Contents Herb Abrams* Marjorie Gross Craig Rutenberg Michael Adler Eileen Horowitz Jay Sanders 3 ......................... -

Annual Report 2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 AGM 24 May 2016, 6:00pm at the RTS, 3 Dorset Rise, London EC4Y 8EN ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY REPORT 2015 PATRONS PRINCIPAL PATRONS IBM BBC IMG Studios BSkyB ITN Channel 4 Television KPMG ITV McKinsey and Co S4C Sargent-Disc INTERNATIONAL PATRONS STV Group Discovery Networks UKTV Liberty Global Virgin Media NBCUniversal International YouView The Walt Disney Company Turner Broadcasting System Inc Viacom International Media RTS PATRONS Networks Autocue YouTube Digital Television Group ITV Anglia MAJOR PATRONS ITV Granada Accenture ITV London Amazon Video ITV Meridian Audio Network ITV Tyne Tees BT ITV Wales Channel 5 ITV West Deloitte ITV Yorkshire Enders Analysis Lumina Search EY PricewaterhouseCoopers FremantleMedia Quantel FTI Consulting Raidió Teilifís Éireann Fujitsu UTV Television Huawei Vinten Broadcast 2 CONTENTS Foreword by RTS Chair and CEO 4 Board of Trustees report to members 6 I Achievements and performance 6 1 National events 6 2 Centres events 34 II Governance and finance 46 1 Structure, governance and management 46 2 Objectives and activities 47 3 Financial review 47 4 Plans for future periods 48 5 Administrative details 48 Independent auditors’ report 50 Financial statements 51 Notes to the financial statements 55 Notice of AGM 2016 66 Agenda for AGM 2016 66 Form of proxy 67 Minutes of AGM 2015 68 Who’s who at the RTS 70 Picture credits 72 Cover: Coronation Street actor Sair Khan speaking from the audience at the RTS early-evening event ‘The secret of soaps: the story behind the stories’ 3 ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY REPORT 2015 FOREWORD his was a busy year for the Society. -

Masterchef Stainless Steel Flatware

5678 Bandini Blvd., Bell, California 90201 Tel: (323) 780-2899 * Fax: (323) 780-3219 www.wingar.com MasterChef stainless steel Flatware Case Illustration Item # Description UPC Code Packing ( 7 84094 ) Cube / 40’ Cnt G.W. 70101-20 Francene 20pc. stainless 701011 6 sets 0.57’ 21,000 sets steel flatware 9.5 lbs 70105-20 Serene 20pc. stainless 701059 6 sets 0.57’ 21,000 sets steel flatware 9.5 lbs 70106-20 Victoria 20pc. stainless 701066 6 sets 0.57’ 21,000 sets steel flatware 9.5 lbs 70101-20T Francene 20pc. flatware 010120 6 sets 1.03’ 11,700 sets w/bonus plastic tray 12.5 lbs 70105-20T Serene 20pc. flatware 010526 6 sets 1.03’ 11,700 sets w/bonus plastic tray 12.5 lbs 70106-20T Victoria 20pc. flatware 010625 6 sets 1.03’ 11,700 sets w/bonus plastic tray 12.5 lbs 70101-24 Francene 24pc. flatware 010113 6 sets 0.70’ 17,100 sets with bonus steak knives 11.0 lbs 70105-24 Serene 24pc. flatware 010519 6 sets 0.70’ 17,100 sets with bonus steak knives 11.0 lbs 70101-45 Francene 45pc. stainless 010144 6 sets 0.84’ 14,400 sets steel flatware 19.8 lbs 70105-45 Serene 45pc. stainless 010540 6 sets 0.84’ 14,400 sets steel flatware 19.8 lbs Illustration Item # Description Packing Cube 8119H-20 Victoria 20pc stainless 6 sets 0.84’ steel flatware set 7123-20 Viva 20pc stainless steel flatware set 8127-20 Prince 20pc stainless steel flatware set 7123-50C Viva 50pc stainless steel 6 sets 1.14’ flatware with wire buffet caddy 8127-50C Prince 50pc stainless steel flatware with wire buffet caddy Illustration Item # Description Packing Cube 76035A Tiffany -

Develops and Publishes Match-3 Game Under Global Brand Masterchef

Develops and publishes match-3 game under global brand MasterChef The mobile game developer Qiiwi Games (Qiiwi) and Endemol Shine Group (ESG) today announce that they have entered into a strategic cooperation agreement to develop and publish one match-3 game for the most successful food entertainment TV programme in the world, MasterChef. MasterChef has been watched by over 300 million people globally, aired in over 200 territories and locally produced in 63 countries and more to come. The collaboration marks the fifth game Qiiwi develops and publishes within the business division "Branded Games" and the first one together with ESG. About MasterChef In MasterChef home cooks compete to be crowned the nation’s MasterChef. Challenges range from simple to advanced cooking tasks. The chefs keep competing through different challenges where contestants are eliminated each time until one is finally crowned the winner. MasterChef is the most travelled food format in the world. To date, 63 countries have launched their own version of the programme and it has been aired in over 200 territories. Since its inception, over 300 million viewers worldwide have tuned in to watch contestants transform their lives through a passion for cooking and the phenomenon shows no signs of slowing down. MasterChef is the number one food brand on YouTube and has generated over 8.2 billion views across YouTube, Facebook and Instagram which leads to a a highly engaged digital global audience. About the agreement between Qiiwi and ESG: Background: Endemol Shine Group together with owner Banijay maintains the world’s largest international content producer and distributor spanning 22 territories with over 120 production companies and a multi-genre catalogue boasting over 88,000 hours of original standout programming. -

Graeme Sinclair

Graeme Sinclair Graeme Sinclair was born in Christchurch, New Zealand on 19 March 1956. He is presently Managing Director of Frontier Television (NZ) Ltd, producing the popular TV series “Gone Fishin”. He is married, to wife Sandra (Sandee) and has two children, James and Amelia. Graeme continues to support Gone Fishin’s sponsors with speaking engagements, hosting fishing trips, function MC, product and sales support. This is his background and his achievements, so far… 2017 Gone Fishin’ Series 24 Continue as Ambassador for Lifemark Produced Ocean Bounty – 13 episode hour- (www.lifemark.co.nz) long documentary series on commercial Speaking engagements continue including fishing. Plastics NZ, Pfizer (Zoetis), Summerset Continue as Patron of NZ Police Bluelight Village Nelson. Speaking engagements continue. Continue as Patron of NZ Police Bluelight 2012 Gone Fishin Series 19 completed including filming in 2016 Gone Fishin Series 23 completed. Norfolk Island and Samoa. Ambassador of Auckland Seafood Festival with Masterchef Brett McGregor. Board member of Southern Seabirds Trust Continue as Patron of NZ Police Bluelight Ambassador for Lifemark Speaking engagements continue. (www.lifemark.co.nz) Speaking engagements continue. 2015 Gone Fishin Series 22 completed. Continue as Patron of NZ Police Bluelight Ambassador of Auckland Seafood Festival 2011 Gone Fishin Series 18 completed. with Masterchef Brett McGregor. Gone Fishin radio show on hold temporarily. Continue as Patron of NZ Police Bluelight “Life on Wheels” published. Continue as Ambassador for Lifemark Patron of the Royal NZ Police College (www.lifemark.co.nz) Recruitment Wing 267 Speaking engagements continue. Gone Fishin Series 19 begins and welcomes a brand new sponsor – TradeZone. -

The Politics of Cooking: Class, Inequality and Power in Masterchef Australia

The Politics of Cooking: Class, Inequality and Power in MasterChef Australia By Robert Lindsay Moore School of Social Sciences Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Arts University of Tasmania October 2017 THE POLITICS OF COOKING: CLASS, INEQUALITY AND POWER IN MASTERCHEF AUSTRALIA This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with Copyright Act 1968. 7 October 2017 ii THE POLITICS OF COOKING: CLASS, INEQUALITY AND POWER IN MASTERCHEF AUSTRALIA Contents Tables and Illustrations v Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 MasterChef Australia 2 Aims and Scope 4 Thesis Outline 5 Literature Review 6 Food and Reality Television 6 Food Television as Reality 9 MasterChef Australia 10 Class Theory and MasterChef Australia 19 The Nature of Reality Television 27 Theoretical Perspectives on Reality Television 31 Identity and ‘Makeover’ in Reality Television 32 Class and Reality Television 34 Tools for Analysis 36 Reading MasterChef Australia 42 Food Dreams 47 Ingredients 51 Cuisine and Technique 61 Personal Presentation 68 Proxemics 78 Conclusion 90 Appendices 94 iii THE POLITICS OF COOKING: CLASS, INEQUALITY AND POWER IN MASTERCHEF AUSTRALIA Appendix 1: Nicolette’s breakdown, E35W07–5 94 Appendix 2: Anatasia’s breakdown E37W08–2 98 Appendix 3: Matt's breakdown E57W12-2 100 Bibliography 104 iv THE POLITICS OF COOKING: CLASS, INEQUALITY AND POWER IN MASTERCHEF AUSTRALIA Tables and Illustrations Table 1: Age groups of MCA contestants 44 Table 2: Occupation groupings of MCA contestants 45 Figure 1: MCA judges, Season 8, E01W01–1.