Cartography As a Witness of Change of Spanish Urban Models Along

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elecciones Al Ayuntamiento Y a La Asamblea De Madrid

1. Resultados electorales 1.1. Resultados de las elecciones al Ayuntamiento y a la Asamblea de Madrid. Escrutinio definitivo por Distritos y barrios 1.2. Resultados de las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo y al Congreso de los Diputados. Escrutinio definitivo por Distritos y barrios. 1.3. Resultados del referéndum sobre la Constitución Europea por Distritos Fuentes, notas y conceptos del Capítulo 16 ANUARIO ESTADÍSTICO 2005 1. Resultados electorales 1.1. Elecciones al Ayuntamiento de Madrid de 25 de mayo de 2003 y a la Asamblea de Madrid de 26 de octubre de 2003. Escrutinio definitivo por Distritos y barrios Absten- Ayuntamiento de Madrid Absten- Asamblea de Madrid Distritos/Barrios Censo Censo ción PP PSOE IU_CM Restoción PP PSOE IU_CM Resto Total municipal (1) 2.483.123 771.510 874.264 625.148 123.015 54.410 2.345.628 793.232 791.306 565.496 129.260 32.378 01. Centro 99.766 32.293 31.986 23.534 7.735 2.946 98.583 38.473 28.705 20.676 8.128 1.309 011. Palacio 18.254 5.499 6.258 4.367 1.378 503 17.974 6.620 5.591 3.857 1.410 215 012. Embajadores 31.961 11.129 8.607 8.119 2.864 895 31.627 13.180 7.570 7.143 2.971 424 013. Cortes 8.183 2.589 2.687 1.876 665 253 8.034 3.068 2.431 1.684 650 106 014. Justicia 12.208 3.708 4.557 2.638 721 421 12.125 4.451 4.201 2.320 821 147 015. -

IPC 18519 Aotero

Asignatura: INMERSIÓN PRECOZ EN LA CLÍNICA Código: 18519 Centro: FACULTAD DE MEDICINA Titulación: MEDICO Nivel: GRADO Tipo: FORMACIÓN BÁSICA Nº de créditos: TRES ASIGNATURA / COURSE TITLE I INMERSIÓN PRECOZ EN LA CLÍNICA / EARLY CLINICAL CONTACT 1.1. Código / Course number 18519 1.2. Materia / Content area La asignatura INMERSIÓN PRECOZ EN LA CLÍNICA (3 ECTS) forma parte de la Materia II.1: INTRODUCCIÓN A LA MEDICINA (11 ECTS), perteneciente al Módulo II : MEDICINA SOCIAL, HABILIDADES DE COMUNICACIÓN E INICIACIÓN A LA INVESTIGACIÓN 1.3. Tipo / Course type Formación obligatoria / Compulsory subject 1.4. Nivel / Course level Grado / Bachelor (first cycle) 1.5. Curso / Year 1º / 1st 1.6. Semestre / Semester 2º Semestre / 2nd semester 1.7. Número de créditos / Credit allotment Tres (3) 1.8. Requisitos previos / Prerequisites Ninguno / None 1 de 9 Asignatura: INMERSIÓN PRECOZ EN LA CLÍNICA Código: 18519 Centro: FACULTAD DE MEDICINA Titulación: MEDICO Nivel: GRADO Tipo: FORMACIÓN BÁSICA Nº de créditos: TRES 1.9. Requisitos mínimos de asistencia a las sesiones presenciales / Minimum attendance requirement - Para ser evaluado es necesario asistir al 80% del total de las sesiones de seminarios y días de estancia en el Centro de Salud, es decir, el alumno deberá asistir al menos a 5 de las 6 sesiones programadas (seminarios, estancias y prácticas en los centros de salud). 1.10. Datos del equipo docente / Faculty data Docente(s) / Lecturer(s) - Coordinador de la asignatura: Prof Dr. Ángel Otero. Profesor Titular de Medicina Preventiva y Salud Pública (Departamento Medicina Preventiva) - Profesores Asociados (Departamento Medicina)* Dra Concepción Álvarez Herrero. Centro de Salud V Centenario. -

1,50 - 2,00 € De La Carrera, La Mejor Manera De Moverse Por La Ciudad –Excepto Para Los Que Vayan Corriendo– Será BILLETE 10 VIAJES · 10 TRIPS TICKET El Metro

26 de abril 2020 abril de 26 Esquema integrado de MetroEsquema de Madrid integrado, TFM, Renfe-Cercanías de Metro de yMadrid Metro , LigeroTFM, Renfe-Cercaníasde la Comunidad dey MetroMadrid Ligero(zona Metro)de la Comunidad de Madrid Metro, Light Rail and SuburbanMetro, LightRail of Rail Madrid and RegionSuburban (Metro Rail zone) of Madrid Region (Metro zone) SIMBOLOGÍA - Key Colmenar Viejo B3 Hospital Cotos Reyes Católicos Infanta Sofía Pinar de Chamartín Transbordo corto ATENCIÓN A LA TARIFA Tres Cantos Puerto de NavacerradaMetro interchange Validación a la SALIDA Baunatal Valdecarros PAY THE RIGHT FARE Alcobendas - Las Rosas Transbordo largo Ticket checked at the EXIT Manuel de Falla Cuatro Caminos Cercedilla Universidad San Sebastián de los Reyes Metro interchange Atención al cliente El Goloso with long walking distance Ponticia Villaverde Alto Los Molinos Customer Service de Comillas Valdelasfuentes Marqués de la Valdavia Moncloa Cambio de tren Aparcamiento disuasorio La Moraleja Argüelles Change of train Cantoblanco Universidad Collado Mediano gratuito Río Manzanares Pinar de Chamartín La Granja El Escorial Metro Ligero Free Park and Ride Alameda de Osuna Light Rail Ronda de la Comunicación Casa de Campo Alpedrete *Excepto días con evento Las Tablas Autobuses interurbanos *Except days with event A B1 B2 Circular Las Zorreras Suburban buses Montecarmelo Palas de Rey 2020 Los Negrales Aparcamiento disuasorio San Yago Autobuses largo recorrido Paco de María Tudor Hospital del Henares de pago Pitis Lucía Río Jarama Pitis Interegional -

Informe De Resultados De La Consulta a Asociaciones Vecinales Relativa Al Estado De La Limpieza En La Ciudad De Madrid

INFORME DE RESULTADOS DE LA CONSULTA A ASOCIACIONES VECINALES RELATIVA AL ESTADO DE LA LIMPIEZA EN LA CIUDAD DE MADRID Madrid, 29 de septiembre de 2016 Informe de resultados de la consulta a las asociaciones vecinales relativa al estado de la limpieza en la ciudad de Madrid. (septiembre 2016) 1. INTRODUCCIÓN La preocupación por la limpieza y el mantenimiento del viario urbano y de espacios públicos como plazas, parques y jardines ha formado parte de las prioridades de las asociaciones vecinales desde su origen, hace casi 50 años. A lo largo de su historia, las entidades ciudadanas no han cesado de defender, a través de acciones de todo tipo, unos barrios y pueblos limpios y saludables. Lo han hecho como hacen con otros asuntos, conjugando la denuncia pública y la protesta en la calle con la negociación y la colaboración con la Administración y los representantes públicos, sean del color que sean. La Federación Regional de Asociaciones Vecinales de Madrid (FRAVM), que aglutina actualmente a 270 entidades de la comunidad autónoma, lleva años alertando del deterioro de los servicios públicos de la capital, incluidos los relativos a limpieza viaria, recogida de basuras y mantenimiento de parques y jardines. Lo hicimos durante el mandato de Alberto Ruiz Gallardón- Ana Botella y lo hacemos ahora con Manuela Carmena, recogiendo siempre el mandato de nuestras asociaciones federadas, que a su vez recogen el sentir de sus vecindarios. Hoy, más allá del uso partidista e interesado que puedan hacer algunas formaciones políticas, la realidad es que esos vecindarios están profundamente preocupados por el déficit de limpieza que padecen los barrios y la ciudad, un problema que el actual equipo de gobierno no ha sido capaz de mejorar en sus 15 meses de andadura. -

Informe De Población Extranjera Enero 2014

INFORME DE LA POBLACIÓN DE ORIGEN EXTRANJERO EMPADRONADA EN LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID ENERO 2014 CONSEJERÍA DE ASUNTOS SOCIALES Elaborado por el Observatorio de InmigraciónInmigración--CentroCentro de Estudios y Datos INFORME DE POBLACIÓN DE ORIGEN EXTRANJERO. ENERO 2014 PORCENTAJE DE POBLACIÓN EXTRANJERA Y ESPAÑOLA EN LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID. Enero 2014 14,28% 930.366 5.585.775 85,72% Población extrajera Población española 2 INFORME DE POBLACIÓN DE ORIGEN EXTRANJERO. ENERO 2014 EVOLUCIÓN DE LA POBLACIÓN EXTRANJERA EN LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID. Enero 2006 - Enero 2014 Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 3 INFORME DE POBLACIÓN DE ORIGEN EXTRANJERO. ENERO 2014 POBLACIÓN EXTRANJERA EN LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID. CRECIMIENTO NETO INTERANUAL. Enero 2006 – Enero 2014 115.975 59.548 51.704 48.314 10.071 -15.521 -47.066 -56.296 -69.742 Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 4 INFORME DE POBLACIÓN DE ORIGEN EXTRANJERO. ENERO 2014 POBLACIÓN EXTRANJERA EN LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID. CRECIMIENTO RELATIVO INTERANUAL. Enero 2006 – Enero 2014 13,92% 5,45% 5,95% 4,56% 0,91% -1,39% -5,10% -4,49% -6,97% Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero Enero 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 5 INFORME DE POBLACIÓN DE ORIGEN EXTRANJERO. ENERO 2014 POBLACIÓN EXTRANJERA EMPADRONADA Y TARJETAS DE RESIDENCIA. Enero 2006-Junio 2013 1.060.606 1.108.920 1.118.991 1.103.470 1.001.058 1.047.174 1.000.108 949.354 974.665 902.816 915.177 938.781 880.613 -

Anexo Iv Hospitales De Referencia Para Centros Y Almacenes Direccion Hospital Nombre Asistencal Noroeste El Escorial C

ANEXO IV HOSPITALES DE REFERENCIA PARA CENTROS Y ALMACENES DIRECCION HOSPITAL NOMBRE ASISTENCAL NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. COLMENAREJO NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. EL ESCORIAL NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. FRESNEDILLA DE LA OLIVA NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. LOS ARROYOS NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. NAVALAGAMELLA NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. NAVALESPINO NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. ROBLEDONDO NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. STA. Mª DE LA ALAMEDA (PUEBLO) NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. STA.Mª. ALAMEDA (ESTACION) NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. VALDEMAQUEDA NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. VALDEMORILLO NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. ZARZALEJO (ESTACION) NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. L. ZARZALEJO (PUEBLO) NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. S. GALAPAGAR NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. S. GUADARRAMA NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. S. ROBLEDO DE CHAVELA NOROESTE EL ESCORIAL C. S. SAN CARLOS NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. ALAMEDA CENTRO FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. ANDRÉS MELLADO NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. ARAVACA NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. ARGÜELLES NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. CÁCERES NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. CASA DE CAMPO NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. DELICIAS NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. EMBAJADORES NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. ISLA DE OZA NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. JUSTICIA NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. LAS CORTES NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. LAVAPIÉS NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. LEGAZPI NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. LINNEO NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. MARÍA AUXILIADORA NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. MARTÍN de VARGAS NOROESTE FUNDACIÓN JIMENEZ DIAZ C. S. -

Madrid Turespa—A

A BURGOS 237 Km A BURGOS 237 Km N-I N-I Av. Monforte de Lemos H CALLE CALLE SINESIO DELGADO Ciudad Residencial PEÑA Parque de ILUSTRACIÓN Sánchez GRANDE Altamira Juan METRO La Ventilla CHAMARTÍN AV. César Manrique EL PILAR C. de Villa Límite i METRO Avenida SANTIAGO C. Melchor Fernández Calle AVDA. Calle de Eladio Vilches Vda. Ganapanes APÓSTOL ESTACIÓN Hortaleza Calle de Ribadavia C. General DE CHAMARTÍN COSTILLARES Avenida de Betanzos CALLE Murias Parque ción NadorMártires C. Est. MADRID ec C. PÍO ir DE LA HIEDRA Los Pinos D Cedros Aranda C. San Ctra. CALLE SINESIO DELGADO de Calle de Julio DáviloCalle de Mesena Calle C. C. Burgos Luis Cº. de Peña Grande Sorolla Calle la los FOXÁ C. la de de de de Ventilla Saavedra PEÑA CALLE XII C. Gómez Hermans de DE Paseo C. Baracaldo Curtidos San de CASTILLA Calle del Baja Molina Antonio Vereda al Barrio del Pilar Emilia CASTELLANA GRANDE C. Cañaveral Leopoldo de Arroyo Calle METRO C. C. Mauricio Legendre J. Castillo de C. DE Parque Agustín VENTILLA METRO Pinos San P C. Marcelina C. DUQUE DE PINAR ANTONIO Rguez. Sahagún CAPITÁN Cantueso ANTONIO A Apolinarde Benito PASTRANA S C. Plátano AGUSTÍN Añastro DEL MACHADO E de Avda. M-30 Alfalfa METRO Calle Caídos de REY San de Fdez. C. C. Ramonet de Jaén Rodríguez C. DELGADO ALMENARA Gredilla Inurria Gerardo Calle Cotrón Calle INTERCAMBIADOR Valdeverdeja DE Calle Calle Sorgo C. Delfín Valderrey BLANCO DE TRANSPORTES Mateo la Div. Azul C. de la Veza METRO Calle C. Agave PLAZA DE SINESIOE. Zurilla LA Calle Calle Calle ATA L AYA CASTILLA Plaza XII Voluntarios de Castilla C. -

Anexo 19 Escuelas Oficiales De Idiomas

Anexo 19 Escuelas Oficiales de Idiomas CLAVE DE IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LAS SIGLAS UTILIZADAS: EOI: ESCUELA OFICIAL DE IDIOMAS; EOI*: EXTENSIÓN DE ESCUELA OFICIAL DE IDIOMAS ORDENACIÓN REALIZADA: 1: DIRECCIÓN DE ÁREA 2: LOCALIDAD 3: DISTRITO 4: BARRIO 5: CÓDIGO POSTAL 6: CÓDIGO DE CENTRO DIRECCIÓN DE ÁREA: MADRID-NORTE COD. C. TIPO NOMBRE DOMICILIO COD.LOC LOCALIDAD DISTRITO BARRIO MUNICIPIO CP ZONA ENSEÑANZAS CON 28042760 EOI E.O.I DE SAN Pasaje La Viña, 3 281340005 San Sebastián San Sebastián 28701 280021 ALEMÁN SEBASTIÁN DE LOS de los Reyes de los Reyes ESPAÑOL REYES FRANCÉS INGLÉS ITALIANO 28062369 EOI E.O.I. DE TRES Calle del Orégano, 1 289030001 Tres Cantos Tres Cantos 28760 280021 ALEMÁN CANTOS FRANCÉS INGLÉS DIRECCIÓN DE ÁREA: MADRID-SUR COD. C. TIPO NOMBRE DOMICILIO COD.LOC LOCALIDAD DISTRITO BARRIO MUNICIPIO CP ZONA ENSEÑANZAS CON 28039712 EOI E.O.I. DE ALCORCÓN Calle del Parque 280070001 Alcorcón Alcorcón 28925 280033 ALEMÁN Grande, 7 ESPAÑOL FRANCÉS INGLÉS ITALIANO 28043284 EOI E.O.I. DE ARANJUEZ Calle Lucas Jordán, 4 280130002 Aranjuez Aranjuez 28300 280033 ALEMÁN FRANCÉS INGLÉS 28041603 EOI E.O.I. DE Calle Islandia, 1 280580001 Fuenlabrada Fuenlabrada 28942 280033 ALEMÁN FUENLABRADA CHINO FRANCÉS INGLÉS 28043302 EOI E.O.I. DE GETAFE Calle del Hospital de San 280650003 Getafe Getafe 28901 280033 ALEMÁN José, 22 FRANCÉS INGLÉS 28041627 EOI E.O.I. DE LEGANÉS Avda Europa, 1 280740002 Leganés Leganés 28915 280033 ALEMÁN ESPAÑOL FRANCÉS INGLÉS ITALIANO 28042747 EOI E.O.I. DE MÓSTOLES Avda del Alcalde de 280920001 Móstoles Móstoles 28933 280033 ALEMÁN Móstoles, 64 FRANCÉS INGLÉS 28042759 EOI E.O.I. -

Cartography As a Witness of Change of Spanish Urban Models Along History Due to Sanitary Crisis

Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies 2021, 7: 1-20 https://doi.org/10.30958/ajms.X-Y-Z COVID-19: Cartography as a Witness of Change of Spanish Urban Models along History Due to Sanitary Crisis By Bárbara Polo Martín* During past centuries, pandemics were something very natural to the human race, but as result of industrialisation during the 19th century, they became a larger problem. The arrival of populations to big cities provoked the development of irregular and overpopulated quarters without any measures of safety, and facilitated the expansion of diseases. The problem resided in sanitation problems, as the example of what happened in London and Paris. As a solution, in different cities, and as a starting point, Paris with the Haussman’s proposals, issued different reforms and extension plans were made in Spain (Nadal 2017, 357- 385). Humanity believed that these extension plans would give us a healthy density and an ordered expansion. We opened big boulevards to believe that we had a wide city to walk, but nothing could be further from reality. At the beginning of 20th century, history repeated itself, and now, a new pandemic crisis has shown that cities have, again, a crisis of congestion. Keywords: cartography, cities, COVID-19, urban models Introduction As a result of a health crisis, speculations on the conditions and perspectives of urban historical centres within the aftermath of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, supported different European cases. Right now, European cities are being hit by the ‗second wave‘ of the worldwide epidemic, and are subjected to different containment strategies and measures. -

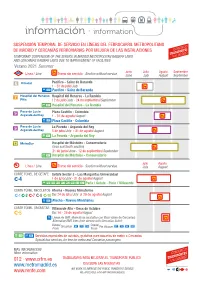

Información · Information

información · information SUSPENSIÓN TEMPORAL DE SERVICIO EN LÍNEAS DEL FERROCARRIL METROPOLITANO DE MADRID Y CERCANÍAS FERROVIARIAS POR MEJORA DE LAS INSTALACIONES TEMPORARY SUSPENSION OF THE SERVICE IN MADRID METROPOLITAN RAILWAY LINES AND CERCANÍAS RAILWAY LINES DUE TO IMPROVEMENT OF FACILITIES Verano 2021 Summer Junio Julio Agosto Septiembre Línea / Line Tramo sin servicio · Section without service June July August September Circular Pacífico - Sainz de Baranda 1 - 31 de julio/July SE Pacífico - Sáinz de Baranda Hospital del Henares Hospital del Henares - La Rambla Pitis 12 de julio/July - 24 de septiembre/September SE Hospital del Henares - La Rambla Paco de Lucía Plaza Castilla - Colombia Arganda del Rey 1 - 31 de agosto/August SE Plaza Castilla - Colombia Paco de Lucía La Poveda - Arganda del Rey Arganda del Rey 5 de julio/July - 31 de agosto/August SE La Poveda - Arganda del Rey MetroSur Hospital de Móstoles - Conservatorio (arco sur/South section) 21 de junio/June - 12 de septiembre/September SE Hospital de Móstoles - Conservatorio Julio Agosto Línea / Line Tramo sin servicio · Section without service July August CORTE TÚNEL DE GETAFE Getafe Sector 3 - Las Margaritas Universidad 1 de julio/July - 31 de agosto/August PN1 PN2 PN3 PE1 PE2 PE3 G1 G2 Parla / Getafe - Pinto / Villaverde CORTE TÚNEL RECOLETOS Atocha - Nuevos Ministerios Del 24 de julio/July al 29 de agosto/August SE Atocha - Nuevos Ministerios CORTE TÚNEL ORCASITAS Villaverde Alto - Doce de Octubre Del 14 - 29 de agosto/August Líneas de EMT alternativas (gratuitas con título válido de Cercanías) Alternative EMT lines (free service with Cercanías ticket) Desde/ Desde/ Orcasitas 60 78 116 Pte. -

El Ayuntamiento De Madrid Abre La VPO a Muchos Más Ciudadanos

EL MUNDO / NÚMERO 531 GUÍA INMOBILIARIA Y DEL HOGAR VIERNES 21 DE MARZO DE 2008 SU VIVIENDA J PROFESIONALES El Ayuntamiento de Madrid abre ENTREVISTA VISOREN. El socio-director de esta compañía, Ramón Ruiz, la VPO a muchos más ciudadanos repasa su principal actividad: la promoción, construcción y explotación de vivienda protegida EL CONSISTORIO ACUERDA UN SISTEMA PARA ADJUDICAR VIVIENDAS PROTEGIDAS QUE COMBINA en régimen de alquiler. El grupo, BAREMACIÓN Y SORTEO Y AMPLIA EL MÍNIMO Y EL MÁXIMO ECONÓMICO PARA OPTAR A ELLAS fruto de la unión de varias constructoras catalanas, prevé dar el salto a Madrid. / PÁGINA 7 BENITO MUÑOZ / MARTA BELVER sos, tanto por arriba (de 5,5 a 7,5 los hogares que se reparten. En ción de viviendas de protección ofi- Se buscan residentes en el muni- veces el Índice Público de Renta de caso de que se produzca un em- cial sea más justa y no quede todo cipio de Madrid con sueldos de en- Efectos Públicos, Iprem) como por pate, se procederá a sortear los en manos del azar. EN PORTADA tre 3.101 y 46.521 euros brutos al debajo (de una a 0,5), el Gobierno pisos, si bien en la rifa podrán par- La inmensa mayoría de los ayun- año. ¿Recompensa? Convertirlos local valorará a partir de ahora el ticipar todos los ciudadanos admi- tamientos de la Comunidad de Ma- CHINA. El gigante asiático en candidatos a optar a una vivien- número de años que el demandan- tidos en el proceso, no sólo los que drid, sin embargo, sigue recurrien- necesita viviendas, oficinas y da de protección oficial mediante te ha estado empadronado en la lo- hayan empatado. -

Proyecto De Mejora De La Accesibilidad Y Supresión De Barreras Arquitectónicas En El Barrio De Valdezarza Del Distrito Moncloa ‐ Aravaca (Madrid)

PROYECTO DE MEJORA DE LA ACCESIBILIDAD Y SUPRESIÓN DE BARRERAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS EN EL BARRIO DE VALDEZARZA DEL DISTRITO MONCLOA ‐ ARAVACA (MADRID) DOCUMENTO Nº4. PRESUPUESTO MADRID Noviembre 2016 PROYECTO DE MEJORA DE LA ACCESIBILIDAD Y SUPRESIÓN DE BARRERAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS EN EL BARRIO DE VALDEZARZA DEL DISTRITO MONCLOA – ARAVACA. (MADRID) DOCUMENTO Nº4. PRESUPUESTO ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDO 1 MEDICIONES 2 CUADROS DE PRECIOS 2.1 CUADRO DE PRECIOS 1 2.2 CUADRO DE PRECIOS 2 3 PRESUPUESTOS PARCIALES 4 PRESUPUESTOS GENERALES 4.1 PRESUPUESTO DE EJECUCIÓN MATERIAL 4.2 PRESUPUESTO BASE DE LICITACIÓN PROYECTO DE MEJORA DE LA ACCESIBILIDAD Y SUPRESIÓN DE BARRERAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS EN EL BARRIO DE VALDEZARZA DEL DISTRITO MONCLOA – ARAVACA. (MADRID) DOCUMENTO Nº4. PRESUPUESTO 1 MEDICIONES MEDICIONES MEDICIONES MEJORA DE LA ACCESIBILIDAD Y SUPRESIÓN DE BARRERAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS EN EL Bº DE VALDEZARZA. MONCLOA-ARAVACA MEJORA DE LA ACCESIBILIDAD Y SUPRESIÓN DE BARRERAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS EN EL Bº DE VALDEZARZA. MONCLOA-ARAVACA (MADRID) (MADRID) CÓDIGO RESUMEN UDS LONGITUD ANCHURA ALTURA CANTIDAD CÓDIGO RESUMEN UDS LONGITUD ANCHURA ALTURA CANTIDAD 01 ACTUACIÓN V02 01.02 MOVIMIENTO DE TIERRAS mU02BD010 m3 EXCAVACIÓN APERTURA DE CAJA 01.01 LEVANTADOS Y DEMOLICIONES Excavación en apertura de caja y carga de productos por medios mecáni- PN06 m DESMONTAJE DE VALLA cos, en cualquier clase de terreno (excepto roca), medida sobre perfil, sin Desmontaje de valla, anclada a la acera o al pavimento, incluso retirada y transporte. NOTA: esta unidad sólo se aplicará cuando la excavación se li- carga de productos, con transporte de los mismos fuera de la obra. mite a la apertura de caja. 1 10,00 10,00 Caja rampa 1 39,15 1,00 39,15 1 27,00 27,00 1 25,25 1,95 49,24 Talud 1 12,60 0,50 6,30 37,00 1 13,40 0,88 11,79 PN04 m DEMOLICIÓN DE BORDILLO 106,48 Demolición de bordillo de cualquier tipo, incluso retirada y carga de produc- tos, medido sobre fábrica, sin transporte.